Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy is an increasing challenge for primary care. Although sometimes clinically justified, polypharmacy can be inappropriate, leading to undesirable outcomes. Optimising care for polypharmacy necessitates effective targeting and monitoring of interventions. This requires a valid, reliable measure of polypharmacy, relevant for all patients, that considers clinical appropriateness and generic prescribing issues applicable across all medications. Whilst there are several existing measures of potentially inappropriate prescribing, these are not specifically designed with polypharmacy in mind, can require extensive clinical input to complete, and often cover a limited number of drugs. The aim of this study was to identify what experts consider to be the key elements of a measure of prescribing appropriateness in the context of polypharmacy.

Methods

Firstly, we conducted a systematic review to identify generic (not drug specific) prescribing indicators relevant to polypharmacy appropriateness. Indicators were subject to content analysis to enable categorisation. Secondly, we convened a panel of 10 clinical experts to review the identified indicators and assess their relative clinical importance. For each indicator category, a brief evidence summary was developed, based on relevant clinical and indicator literature, clinical guidance, and opinions obtained from a separate patient discussion panel. A two-stage RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method was used to reach consensus amongst the panel on a core set of indicators of polypharmacy appropriateness.

Results

We identified 20,879 papers for title/abstract screening, obtaining 273 full papers. We extracted 189 generic indicators, and presented 160 to the panel grouped into 18 classifications (e.g. adherence, dosage, clinical efficacy). After two stages, during which the panel introduced 18 additional indicators, there was consensus that 134 indicators were of clinical importance. Following the application of decision rules and further panel consultation, 12 indicators were placed into the final selection. Panel members particularly valued indicators concerned with adverse drug reactions, contraindications, drug-drug interactions, and the conduct of medication reviews.

Conclusions

We have identified a set of 12 indicators of clinical importance considered relevant to polypharmacy appropriateness. Use of these indicators in clinical practice and informatics systems is dependent on their operationalisation and their utility (e.g. risk stratification, targeting and monitoring polypharmacy interventions) requires subsequent evaluation.

Trial registration

Registration number: PROSPERO (CRD42016049176).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The use of multiple medications in a single individual (polypharmacy) is a global phenomenon, creating new challenges for many health services [1], driven by increasing levels of multimorbidity [2] and a culture of single-condition guideline-based prescribing [3].

Polypharmacy is associated with several undesirable consequences [4,5,6,7,8]. However, we have previously demonstrated that the association between polypharmacy and adverse outcomes is attenuated in the most multimorbid individuals [9]. This suggests that overly simplistic analyses of polypharmacy, relating simple medication counts to adverse outcomes, may be misleading [9, 10]. Polypharmacy is typically measured using arbitrary numeric thresholds, but these fail to capture medication appropriateness; therefore, more sophisticated approaches accounting for clinical context are required.

A number of prescribing indicators that assess medication appropriateness are considered to have face validity [11], and may have value in improving quality and reducing adverse outcomes [12]. However, such indicators generally do not account for multiple drug use and do not measure polypharmacy per se. In addition, explicit ‘drug specific’ indicators (e.g. Beers criteria [13]) do not apply to all patients, and implicit measures (e.g. the Medication Appropriateness Index [14]) require time consuming input from an experienced clinician.

There is therefore a need to develop a valid and reliable means of measuring polypharmacy that takes account of clinical appropriateness. Further, a framing of polypharmacy appropriateness (rather than appropriate or inappropriate polypharmacy) acknowledges a spectrum of prescribing within the context of polypharmacy, including the need to support individualised prescribing approaches where potentially risky (or ‘inappropriate’) combinations may be fitting for a particular patient. To be usable in clinical practice, this measure should ideally focus on generic prescribing issues (to ensure relevance to all patients, and avoiding simply focusing on a finite number of medications, i.e. implicit indicators), whilst still permitting automation as part of a computerised clinical system. We anticipate that this measure of polypharmacy appropriateness would enable more effective targeting and evaluation of medication optimisation interventions. Used as a first step in identifying which patients may be at risk of inappropriate prescribing, such a measure could facilitate targeted conversations with patients to subsequently ascertain their views on the appropriateness of their current medication regimen.

Methods

The aim of this study was to identify the key elements of a measure of prescribing appropriateness in the context of polypharmacy. We conducted a systematic review and RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method consensus study, as outlined below. Whilst our aim was to develop a measure of polypharmacy appropriateness, the orientation of most measures to date has been one of inappropriate prescribing, and we therefore adopt that terminology when referencing existing approaches.

Systematic review of indicators of polypharmacy appropriateness

To locate and derive implicit indicators of polypharmacy appropriateness for consideration by the expert panel, an initial systematic review was undertaken. The protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42016049176) [15, 16] and the manuscript was written in accordance with the PRISMA statement [17].

Search strategy

We searched Embase, MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycINFO, CINAHL, Health Management Information Consortium, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, the Trip and NHS Evidence databases, from 1992 (the year the Medication Appropriateness Index was first published [14]) until October 10, 2016. Search terms were developed in collaboration with an experienced medical librarian. We used exploded MeSH terms (e.g. inappropriate prescribing) and combinations of relevant keywords and their variants (e.g. medication, drug therapy, drug utilisation, drug utilisation review, prescribing). We adapted our initial MEDLINE search strategy (Box 1) to run in the additional databases, and to perform a review of reviews to identify any previous reviews in this field (Box 2). Further relevant publications were identified by a manual search of references and citations of included papers.

Inclusion criteria

Articles were eligible for inclusion if they reported the use of a specific tool to assess polypharmacy or inappropriate prescribing, including both implicit and explicit indicators. We defined ‘implicit’ (or ‘generic’) indicators as judgement-based indicators that facilitate the consideration of the whole patient, rather than having a narrow focus on specific drugs or diseases [11]. We defined ‘explicit’ indicators as criterion-based indicators that assess specific drug-based or disease-based prescribing against specific standards derived from guidelines or expert opinion [11].

The decision to include both implicit and explicit indicators at full-text screening, rather than including only articles stating the focus was on implicit indicators, was based on our observation that implicit indicators were not always clearly identified as such. For example, a single implicit indicator may be embedded within instruments labelled as explicit indicators, as is the case with the guidelines developed by Basger et al. [18, 19] in the Australian context. We excluded papers describing non-instrument based medication reviews, educational interventions, validation studies of previously published tools, general guidelines and recommendations relating to assessing inappropriate prescribing, and articles not published in English.

Screening

Publications were assessed for eligibility by title and abstract screening. An initial random sample of 100 titles/abstracts was triple screened to refine the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. A single reviewer (NE) subsequently screened all titles/abstracts, with a 10% random sample screened by two additional reviewers (JB, RP). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the three reviewers. Articles included for full text screening were retrieved and reviewed against the inclusion criteria by two reviewers (NE and JB) independently, with discrepancies resolved by discussion with RP.

Extraction of indicators

All full-text papers meeting the inclusion criteria were reviewed to find implicit indicators of polypharmacy or inappropriate prescribing. Indicators were extracted and subjected to qualitative content analysis to identify categories into which they could be grouped [20]. Two authors (JB and RP) independently reviewed all indicators and generated a coding framework, which was refined through consensus discussions to produce a final set of indicator categories. Indicators that, on further scrutiny, were deemed not to be truly implicit were excluded at this stage. All indicators, within their categories, were subsequently taken forward for expert review in a consensus panel.

Quality assessment of indicators

Where stated, the development method for the identified indicators was extracted, and its strengths and limitations were assessed with reference to the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist for text and opinion [21].

Expert consensus process

The two-stage RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method was employed to reach consensus on indicators of prescribing considered by experts to be key to a measure of polypharmacy appropriateness. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method is a well-established approach for systematically generating expert consensus by combining scientific evidence with expert opinion, and subsequently aggregating individual opinions into a single perspective [22].

Patient views

We convened a panel of five patient representatives from a local ‘patient and public involvement in research’ group to gather their views on which aspects of polypharmacy and prescribing identified by the systematic review were of particular relevance and concern to them. The panel meeting was facilitated by a general practitioner (RP), with support from a specialist Patient and Public Involvement coordinator responsible for facilitating patient involvement in research [23]. The categories of polypharmacy or inappropriate prescribing into which the identified indicators had been grouped were presented to the panel, and discussion encouraged around the particular importance or relevance of this area to the patient experience. Patient representatives were asked, in particular, to reflect on the relevance and importance of each prescribing indicator category, whether doing something about it would make a difference, the potential challenges of measuring it, and whether they would prioritise one or more categories. Field notes were taken during the conduct of the panel meeting and key points across each category were summarised. A synopsis of the patient views in relation to each category was presented in narrative form in the evidence summaries supplied to the expert panel (see below).

Evidence summaries

For each indicator category, the research team developed a corresponding brief evidence summary. These summaries drew upon clinical and academic literature, and addressed the importance and relevance of the issue in relation to polypharmacy, the potential consequences for patients, and how the indicators had been developed and evaluated. As outlined above, patient views were also incorporated based on the earlier patient panel discussion. Evidence summaries were then presented to panel members to support discussions as part of the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method consensus exercise; these included a brief summary of the strengths and weaknesses of the approach to deriving each included indicator, as derived from the quality assessment of indicators.

Expert panel members

We undertook a snowball approach to recruit expert panel members, aiming to include a range of professions and levels of experience. We particularly focused on individuals immersed in the general prescribing process and those who regularly dealt with polypharmacy; we therefore targeted general practice, pharmacy, pharmacology, and geriatric medicine. We therefore approached relevant professional organisations, including the Royal College of General Practitioners, Royal Pharmaceutical Society, British Pharmacological Society, and additional known contacts of the research team. Our final ten-member panel consisted of four general practitioners, two pharmacists, three geriatricians, and one clinical pharmacologist; RAND/UCLA approaches typically include anything from 7 to 15 members in a panel [22]. Panel members were not involved in the systematic review itself.

First stage assessment

In stage one, we asked panel members to participate in an online survey to evaluate the implicit indicators of inappropriate prescribing or polypharmacy identified through the systematic review. Panel members were sent a personalised link to complete the first stage of ratings using the survey software, Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com). Indicators were presented to panel members in their category groupings. Panel members were asked to review the indicators within each category and score each indicator in turn in relation to (1) its clinical importance with regards to polypharmacy and (2) its clarity, using a rating scale numbered 1 to 9, where a score of 1 meant the indicator was extremely unimportant (or unclear) in evaluating polypharmacy appropriateness, and a score of 9 meant the indicator was extremely important (and clear). Consensus classifications for each indicator were established using a series of rules, outlined in Table 1.

Second stage assessment

In stage two, we convened a face-to-face meeting of all panel members to further review and discuss indicators and their scores. The meeting was facilitated by an experienced RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method facilitator (SC) with input from a general practitioner with expertise in polypharmacy (RP). Anonymised frequency distributions and median scores for the clinical importance rating of every stage one indicator were provided to each panel member at the start of the meeting, alongside the scores they had themselves assigned to every indicator. Categories of indicator were discussed, in turn, with panel members given the opportunity to suggest changes to the wording of the indicators; the wording of all new variations of indicators needed to be agreed by all panellists. At the end of discussions around each category, panel members were asked to rate each indicator again, including new variations, in relation to their clinical importance to polypharmacy.

Application of final decision rules

As indicators considered by the panel were presented in categorical groupings, many indicators, whilst drawn from different sources, were closely related. To ensure our final indicator set was a non-duplicative measure of polypharmacy appropriateness, we took the following steps. First, in order to decide which of the highest scoring indicators within each category to take forward to the final set, two members of the research team (JB and RP) independently coded indicators within each category grouping to identify sub-category groupings, which were further refined through discussion with two other team members (AA and SR). The highest scoring indicator from each sub-category grouping was subsequently taken forward; all such indicators scored a minimum of 7. Where more than one indicator in each sub-category had the same highest score, the decision as to which indicator to select was made within the research team through discussion and consideration of the likely feasibility of the operationalisation of that indicator in primary care. We then applied the following decision rules to the remaining indicators:

-

1.

Able to be applied at the level of individual drugs

-

2.

Not overlapping with or duplicating another indicator

The final suggested list was circulated to the panel members for any last comments and review.

Results

Systematic review

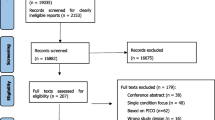

Our review identified 20,879 papers for title/abstract screening, from which 273 full-text papers were identified for review (Fig. 1). Double screening of a 10% random sample of all citations had a 97% consensus rate, with both reviewers making the same decision. Following full text screening, we selected 17 papers that included either all implicit or a mixture of implicit and explicit indicators. A further five papers were identified through forward and backward citation searching of the 17 papers. From the resulting 22 papers (Appendix 1), we identified 189 potential implicit indicators of polypharmacy or inappropriate prescribing. On further scrutiny, 29 indicators did not meet our inclusion criteria. The remaining 160 indicators (Additional file 1) were placed into 18 categories derived through content analysis (Box 3). The wording of each indicator remained unchanged from its original source and thus, at this stage, categories could contain similar indicators varying only slightly in their wording or grammatical construction.

Patient panel

Although patient representatives discussed all of the prescribing indicator categories, they prioritised adherence, drug–drug interactions and clinical efficacy as fundamental to polypharmacy appropriateness. They raised concerns about how feasible it was to evaluate adherence, but felt it was a central issue for patients managing complex medication regimens. The avoidance of adverse drug–.drug interactions was also seen as vital; the patient panel stated that they looked to clinical expertise to evaluate and avoid these risks for patients. Finally, discussions on the role of clinical efficacy focused on how specific this was to the individual, and patient representatives voiced concerns raised about how clinicians could evaluate and optimise the overall efficacy of a complex medical regimen for each patient. Cost-effectiveness was seen as relevant but not a core consideration, although patient representatives agreed with the prescribing of generic medications where possible.

RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method

In stage one, the 160 indicators identified from the systematic review were presented to the panel for consideration and rating. In the stage two face-to-face meeting, panel discussions led to the introduction of 18 re-worded or new indicators, giving a total pool of 178 indicators for consideration. There was panel consensus that 134 indicators were of clinical importance (scoring a median rating of 7 or above); for a further 5 indicators, the panel was equivocal as to clinical importance. The panel agreed that 19 indicators were not of clinical importance, and they did not reach consensus about the importance of 20 indicators. There was a notable lack of prioritisation of, and consensus around, indicators relating to cost-effectiveness, and all indicators in this group were eliminated at this stage.

The remaining 134 indicators represented 17 categories, from which we derived 29 sub-categories. Application of the agreed decision rules led to a final listing of 12 indicators (Table 2 and Box 4), which, in consultation with the panel, were re-worded to be consistent in the use of terminology (e.g. ‘drug’ rather than ‘medication’), grammar (e.g. statements rather than questions) and positive-versus-negative framing. These came from nine previously developed indicator lists (one indicator from each of seven existing lists [14, 24,25,26,27,28,29] and two indicators each from a further two lists [30, 31]). The panel introduced one entirely new indicator during stage two discussions. The final suggested list was circulated to the panel members for final comment and agreement; minor rewording was suggested and agreed for three indicators as a result (indicators 2, 7, and 11), most notably the insertion of ‘hepatic status’ into indicator 7 (the drug as currently prescribed is not likely to be sub-therapeutic or toxic, based on the dose, route and dosing interval for the age, renal and hepatic status of the patient).

Discussion

We have identified a set of 12 indicators of prescribing appropriateness suitable for use in the context of a patient with polypharmacy. We are currently operationalising these indicators for use in clinical practice and informatics systems, with the aim of facilitating risk stratification, and the targeting and monitoring of polypharmacy interventions.

Our review identified a proliferation of implicit indicators of inappropriate prescribing; our final set of 12 indicators of polypharmacy appropriateness originated from nine different existing measures, including the influential Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) [14, 32]. The MAI is comprised of 10 questions, completed by a pharmacist or physician in order to assess the appropriateness of a drug. It has been widely used as an outcome measure in randomised trials of interventions to improve prescribing; however, its authors specifically state that, whilst it is suited to identifying instances of potentially inappropriate prescribing, it was not developed to identify sub-optimal prescribing in the context of polypharmacy [32]. Whilst only one of our indicators was directly derived from those within the MAI, it is important to note that our final list overlaps with the MAI in many ways, suggesting both that a number of core constructs of inappropriate polypharmacy (including indication, effectiveness and interactions) were captured well by this measure, and that subsequent measures of inappropriate prescribing may have been replicating much of the original MAI work.

However, areas of clinical importance not captured by the MAI were also selected by our expert panel, reflecting our particular focus on the context of multiple medications. These included patient adherence, the complexity of the medication regimen and the availability of non-pharmacological alternatives. Determinants of patient adherence are complex; specific factors, including frequent dosing, longer duration of treatment and the presence of adverse effects, may all decrease adherence [33]. Medication regimen complexity is negatively associated with levels of adherence in patients, and medications become increasingly complex with increasing levels of polypharmacy [34]. Increased toxicity as a consequence of multiple medicines [35] may be reduced by using other treatment options. Lifestyle measures and non-pharmacological treatments are key alternative therapeutic options for a range of clinical conditions commonly found in patients with polypharmacy, including depression and cardiovascular risk management [36, 37].

The importance of a regular full review of prescribed medications was formulated as a new indicator specifically following panel discussion. Systematically conducted medication reviews have been shown to be of particular importance to patients with polypharmacy [38] and have been recommended for those over 75 taking multiple drugs. Not conducting regular medication reviews, particularly for those prescribed multiple drugs, places patients at greater risk of potential harm [39]. However, current evidence is limited on the clinical effectiveness of systematically conducted medication review for reducing the suboptimal use of medicines and improving patient-reported outcomes [40].

Cost-effectiveness was included in a number of identified instruments, including the MAI, but discarded by our panel. Their view was that cost-effectiveness in prescribing (typically defined as ensuring that medication is both clinically and economically appropriate for the conditions [41]) was not, in itself, a marker of polypharmacy appropriateness; instead, they viewed cost-effectiveness as a potentially positive consequence of patient-centred medicines optimisation. Our patient panel, too, echoed this opinion, agreeing simply that the prescribing of generic drugs, when available and when cheaper than branded products, was a sensible approach.

A number of strengths and limitations of this study are worth acknowledging. We have conducted a large-scale systematic review, supported by an experienced medical librarian, and followed a well-established consensus method with a diverse expert panel. As polypharmacy is relevant to all ages, we placed no restrictions on age in our analyses in order to ensure the generalisability of the findings. To locate all potentially relevant indicators, we used a high sensitivity, low precision search strategy; we acknowledge the subsequent high citation screening workload (with only 10% double screening) may have therefore resulted in important relevant citations being missed. Most of the indicators located, reviewed and evaluated for clinical importance had previously been subject to robust development processes, increasing our confidence in their face and content validity. However, we note that it is possible we missed additional relevant indicators if they were not readily identifiable as implicit measures of appropriate prescribing or polypharmacy. Whilst we recruited a wide range of experts to the panel, they may not be representative of all healthcare professionals involved in caring for patients with polypharmacy. The lack of international perspectives on the panel, which was convened only from UK participants, may reduce the applicability of our findings to other contexts. Following our stage two panel meeting, we developed and applied additional decision rules to produce a non-duplicative and coherent indicator list; whilst this was done in consultation with the panel, we acknowledge that other research teams may have made different decisions about which indicators to retain. Additional work will be necessary to explore the acceptability and operationalisation of the chosen indicators within clinical systems, and to ascertain their utility for risk stratification, targeting and monitoring of polypharmacy interventions. This work will additionally consider issues such as whether indicators should be weighted in an assessment of polypharmacy appropriateness. Finally, we note that this approach does not by itself facilitate the inclusion of patient perspectives of polypharmacy appropriateness. Whilst our proposed measure, when operationalised, may highlight patients where there are clinical concerns about medication regimen, it cannot offer a holistic assessment of the appropriateness of the regimen, where the patients’ perspectives must be central to any decisions about care.

Conclusions

This study has integrated and adapted existing indicators of appropriate prescribing, and introduced a new one, to produce a short, yet comprehensive list of 12 indicators suitable to the assessment of prescribing appropriateness in a patient with polypharmacy. Use of these indicators in clinical practice and informatics systems is dependent on their operationalisation, and their utility (e.g. risk stratification, targeting and monitoring polypharmacy interventions) requires subsequent evaluation.

References

Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R, et al. Polypharmacy and Medicines Optimisation: Making it Safe and Sound. London: King’s Fund; 2013.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380:37–43.

Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.6.716.

Avery AJ, Ghaleb M, Barber N, et al. The prevalence and nature of prescribing and monitoring errors in English general practice: a retrospective case note review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e543–53. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X670679.

Dequito AB, Mol PGM, van Doormaal JE, et al. Preventable and non-preventable adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Drug Saf. 2011;34:1089–100. https://doi.org/10.2165/11592030-000000000-00000.

Fincke BG, Miller DR, Spiro A. The interaction of patient perception of overmedication with drug compliance and side effects. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:182–5. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00053.x.

Vik SA, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Measurement, correlates, and health outcomes of medication adherence among seniors. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:303–12. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1D252.

Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Korhonen MJ, et al. Polypharmacy status as an indicator of mortality in an elderly population. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:1039–48. https://doi.org/10.2165/11319530-000000000-00000.

Payne RA, Abel GA, Avery AJ, et al. Is polypharmacy always hazardous? A retrospective cohort analysis using linked electronic health records from primary and secondary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:1073–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12292.

Appleton SC, Abel GA, Payne RA. Cardiovascular polypharmacy is not associated with unplanned hospitalisation: evidence from a retrospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-58.

Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet. 2007;370:173–84.

Hill-Taylor B, Walsh KA, Stewart S, et al. Effectiveness of the STOPP/START (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment) criteria: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41:158–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12372.

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13702.

Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1045–51.

Elmore N, Burt J, Payne R, et al. Developing and Evaluating a Measure of Inappropriate Polypharmacy in Primary Care. PROSPERO 2016 CRD42016049176. PROSPERO. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42016049176. Accessed 9 Mar 2018.

Burt J, Elmore N, Rodgers S, et al. Developing and Evaluating a Measure of Inappropriate Polypharmacy in Primary Care. Cambridge: Primary Care Unit, University of Cambridge; 2016. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPEROFILES/49176_PROTOCOL_20160910.pdf

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. Accessed 9 Mar 2018.

Basger BJ, Chen TF, Moles RJ. Inappropriate medication use and prescribing indicators in elderly Australians: development of a prescribing indicators tool. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:777–93.

Basger BJ, Chen TF, Moles RJ. Validation of prescribing appropriateness criteria for older Australians using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001431. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001431.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools - JBI. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html. Accessed 16 Mar 2018.

Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2001. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269.html

INVOLVE. Public Involvement in Research: Values and Principles Framework – INVOLVE. Southampton (UK): INVOLVE 2015. http://www.invo.org.uk/posttypepublication/public-involvement-in-researchvalues-and-principles-framework/. Accessed 16 Mar 2018.

Drenth-van Maanen AC, van Marum RJ, Knol W, et al. Prescribing optimization method for improving prescribing in elderly patients receiving polypharmacy: results of application to case histories by general practitioners. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:687–701. https://doi.org/10.2165/11316400-000000000-00000.

Lenaerts E, De Knijf F, Schoenmakers B. Appropriate prescribing for older people: a new tool for the general practitioner. J Frailty Aging. 2013;2:8–14. https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2013.2.

Alfaro Lara ER, Vega Coca MD, Galván Banqueri M, et al. Selection of tools for reconciliation, compliance and appropriateness of treatment in patients with multiple chronic conditions. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:506–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2012.06.007.

Bergman-Evans B. Evidence-based guideline. Improving medication management for older adult clients. J Gerontol Nurs. 2006;32:6–14.

Cantrill JA, Sibbald B, Buetow S. Indicators of the appropriateness of long-term prescribing in general practice in the United Kingdom: consensus development, face and content validity, feasibility, and reliability. Qual Health Care QHC. 1998;7:130–5.

Hamdy RC, Moore SW, Whalen K, et al. Reducing polypharmacy in extended care. South Med J. 1995;88:534–8.

Tully MP, Javed N, Cantrill JA. Development and face validity of explicit indicators of appropriateness of long term prescribing. Pharm World Sci PWS. 2005;27:407–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-005-0340-1.

Newton PF, Levinson W, Maslen D. The geriatric medication algorithm: a pilot study. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:164–7.

Hanlon JT, Schmader KE. The Medication Appropriateness Index at 20: where it started, where it has been, and where it may be going. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:893–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0118-4.

Kardas P, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol 2013;4:91. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00091.

Lam PW, Lum CM, Leung MF. Drug non-adherence and associated risk factors among Chinese geriatric patients in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:284.

Juurlink DN, Mamdani M, Kopp A, et al. Drug-drug interactions among elderly patients hospitalized for drug toxicity. JAMA. 2003;289:1652–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.13.1652.

Dirmaier J, Steinman MA, Krattenmacher T. Non-pharmacological treatment of depressive disorders: a review of evidence-based treatment options. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2012;7:141–9.

NICE. Cardiovascular Disease: Risk Assessment and Reduction, Including Lipid Modification. NICE; 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG181. Accessed 1 June 2018.

Krska J. Pharmacist-led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized, controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing. 2001;30:205–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/30.3.205.

Sorensen L, Stokes JA, Purdie DM, et al. Medication reviews in the community: results of a randomized, controlled effectiveness trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:648–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02220.x.

NICE. Medicines Optimisation: The Safe and Effective Use of Medicines to Enable the Best Possible Outcomes. NICE 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5/resources/medicines-optimisation-the-safe-and-effective-use-of-medicines-to-enable-the-best-possible-outcomes-51041805253. Accessed 30 Nov 2016.

Whitburn S. Prescribing the Cost-effective Way. GP. 2007; http://www.gponline.com/prescribing-cost-effective/article/662699. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Buetow SA, Sibbald B, Cantrill JA, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate long term prescribing in general practice in the United Kingdom, 1980–95: systematic literature review. BMJ. 1996;313:1371–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.313.7069.1371.

Caughey GE, Ellett LMK, Wong TY. Development of evidence-based Australian medication-related indicators of potentially preventable hospitalisations: a modified RAND appropriateness method. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004625. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004625.

Fried TR, Niehoff K, Tjia J, et al. A Delphi process to address medication appropriateness for older persons with multiple chronic conditions. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0240-3.

Gazarian M, Kelly M, McPhee JR, et al. Off-label use of medicines: consensus recommendations for evaluating appropriateness. Med J Aust. 2006;185:544–8.

Hassan NB, Ismail HC, Naing L, et al. Development and validation of a new Prescription Quality Index: Prescription quality. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:500–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03597.x.

Johnson KA, Nye M, Hill-Besinque K, et al. Measuring the impact of patient counseling in the outpatient pharmacy setting: development and implementation of the counseling models for the Kaiser Permanente/USC Patient Consultation Study. Clin Ther. 1995;17:988–1002.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu145.

Stange D, Kriston L, Langebrake C, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Medication Regimen Complexity Index (MRCI-D): Medication Regimen Complexity Index - German translation and evaluation. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:515–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01636.x.

Tommelein E, Petrovic M, Somers A, et al. Older patients’ prescriptions screening in the community pharmacy: development of the Ghent Older People’s Prescriptions community Pharmacy Screening (GheOP3S) tool. J Public Health. 2016;38:e158–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv090.

van Dijk KN, Pont LG, de Vries CS, et al. Prescribing indicators for evaluating drug use in nursing homes. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:1136–41.

Winslade NE, Bajcar JM, Bombassaro AM, et al. Pharmacist’s management of drug-related problems: a tool for teaching and providing pharmaceutical care. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:801–9.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Isla Kuhn for her expert assistance with developing and conducting database searches in the systematic review. We are deeply grateful to all the panel members and patients who contributed to this study.

Funding

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR) (Ref. SPCR-2014-10043). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Availability of data and materials

For further details of the data, please contact the corresponding author Jenni Burt jenni.burt@thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB designed the study, oversaw the systematic review, drafted the evidence summaries, helped convene the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method consensus panel, oversaw the development of the final set of indicators and drafted the paper. NE conducted the systematic review, drafted the evidence summaries, organised the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method consensus panel, and reviewed the final draft of the paper. SC contributed to the design of the study, chaired the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method consensus panel, and reviewed the final draft of the paper. SR contributed to the design of the study, gave advice on the development of the indicators, and reviewed the final draft of the paper. AA contributed to the design of the study, gave advice on the development and categorisation of the indicators, and reviewed the final draft of the paper. RAP designed the study, oversaw the systematic review, drafted the evidence summaries, helped convene the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method consensus panel, oversaw the development of the final set of indicators, and drafted the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was received from the University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee on 13 October 2016 (ref PRE.2016.073). All participants in the RAND Consensus Panel gave written signed consent for the study.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table of included indicators, by category grouping. (DOCX 67 kb)

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Burt, J., Elmore, N., Campbell, S.M. et al. Developing a measure of polypharmacy appropriateness in primary care: systematic review and expert consensus study. BMC Med 16, 91 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1078-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1078-7