Abstract

Background

About 5% of the global population, predominantly in low- and middle-income countries, is forced into poverty because of out-of-pocket (OOP) health spending. In most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the share of OOP health spending in current health expenditure exceeds 35%, increasing the likelihood of impoverishment. In Ethiopia, OOP payments remained high at 37% of current health expenditure in 2016. This study assesses the impoverishment resulting from OOP health spending in Ethiopia and the associated factors.

Methods

This paper uses data from the Ethiopian Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2010/11. The HCES covered 10,368 rural and 17,664 urban households. OOP health spending includes spending on various outpatient and inpatient services. Impoverishing impact of OOP health spending was estimated by comparing poverty estimates before and after OOP health spending. A probit model was used to assess factors that are associated with impoverishment.

Results

Using the Ethiopian national poverty line of Birr 3781 per person per year (equivalent to US$2.10 per day), OOP health spending pushed about 1.19% of the population (i.e. over 957,169 individuals) into poverty. At the regional level, impoverishment ranged between 2.35% in Harari and 0.35% in Addis Ababa. Living in rural areas (highland, moderate, or lowland) increased the likelihood of impoverishment compared to residing in an urban area. Households headed by males and adults with formal education are less likely to be impoverished by OOP health spending, compared to their counterparts.

Conclusion

In Ethiopia, OOP health spending impoverishes a significant number of the population. Although the country had piloted and initiated many reforms, e.g. the fee waiver system and community-based health insurance, a significant proportion of the population still lacks financial protection. The estimates of impoverishment from out-of-pocket payments reported in this paper do not consider individuals that are already poor before paying out-of-pocket for health services. It is important to note that this population may either face deepening poverty or forgo healthcare services if a need arises. More is therefore required to provide financial protection to achieve universal health coverage in Ethiopia, where the informal sector is relatively large.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Understanding the nexus between poverty and (ill) health is essential for development, especially within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1,2,3]. Poverty levels remain high in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), accounting for 42% of global extreme poverty headcount in 2013 [4]. While poverty levels are high, another possible contributor to poverty, out-of-pocket (OOP) health spending, was estimated at 35% of current health expenditure in SSA in 2016 [5]. Generally, OOP health spending that is greater than 20% of current health expenditures reduces the likelihood of financial protection in a country’s health system [6]. In SSA, OOP health spending exceeds 20% of current health expenditure in more than 70% of the countries [5], predisposing a substantial proportion of the population to impoverishment [7]. In 2010, globally, over 95 million people were impoverished by OOP health spending, falling below the $1.90 international poverty line [3]. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that each year, OOP health spending impoverishes up to 5% of the global population [8], but standard poverty measures do not account for this impoverishing effect of OOP health spending [7].

Ethiopia, like most countries in SSA, finances health services, among other mechanisms, through OOP health spending which has increased from 33.7% (in 2010/2011) [9] to 37.0% (in 2016) of the country’s current health expenditure [5]. Private health centres and clinics – including all types of clinics – account for 65.7% of all health centres in Ethiopia [10]. User fees still exist at public facilities, and private facilities charge OOP for health services. The significant number of private health centres implies that a substantial number of people would be seeking care from private facilities, incurring significant OOP health spending. Public health facilities in Ethiopia implement a fee-waiver system aimed at exempting the poorest from fees.

Since 1999/2000, Ethiopia has contemplated different health financing reforms that aimed at both the supply-side (the first generation reforms – strengthening the health system) and demand-side (the second generation reforms – introducing health insurance schemes) to improve the attainment of the health system goals [11]. Increasing health system resources by improving efficiency and raising more revenue was one of the major policy objectives in the first-generation reforms. In fact, most of the supply-side reforms contribute to this objective. Some of these reforms were revenue raising and retention by healthcare facilities, improving the fee-waiver system, establishing a private wing in public facilities, and outsourcing of non-clinical services. As a result of these reforms, there was a significant increase in health sector resources. For instance, per capita health expenditure increased from $5.60 (1999/00) to $7.14 (2004/05) and $20.77 (2010/11) [9]. However, the impact of the first generation reforms in reducing OOP health spending was minimal. OOP health spending as a share of current health expenditure dropped only by two percentage points between 1999/00 (36%) and 2010/11 (34%)Footnote 1 as reported in the Ethiopian National Health Accounts [9, 12]. The existence of high OOP health spending remained a critical issue in policy documents, and among the reforms proposed were establishing health insurance schemes; which are considered to be the second generation reforms [11, 13]. Social health insurance (SHI) was established under the proclamation number 690/2010 of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE), while community-based health insurance (CBHI) has been piloted since mid-2011 in different regions of the country [14,15,16]. The health insurance system is still in the early development stages, and more is needed to contribute to a significant reduction in OOP health spending below 20% of current health expenditure to guarantee financial protection.

In Ethiopia, an assessment of the impoverishing impact of OOP health spending in 2004 report that less than 1% of the population was pushed into poverty [17]. However, levels of impoverishment vary by household characteristics. For instance, a higher rate of impoverishment (5.8% points) is reported for households of persons with depression compared to households without persons with depression [18]. These findings suggest the need for further studies on the factors associated with impoverishment and an update in the assessment of poverty levels related to OOP health spending using recent datasets. Such a study can also show the impact of health financing reforms that were introduced since 1999/00. This paper, therefore, assesses the effect of OOP health spending on monetary poverty in Ethiopia to evaluate the country’s progress in achieving universal financial protection. It also examines the factors that are associated with impoverishing OOP health spending.

Methods

Data

This paper uses the Ethiopian Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2010/11, the latest data available when this study was conducted. The HCES is a nationally representative survey conducted by the Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency using the 2007 Population and Housing Census sampling frame. The HCES uses a two-stage stratified sampling design. The first stage involved the selection of 864 rural and 1104 urban Enumeration Areas (EAs) from the 11 regions of the country except for some areas in two regions with a nomadic population. A total of 10,368 rural and 17,664 urban households are selected from the sampled EAs [19]. The HCES contains data on household expenditure on goods and services, including OOP payments for various health services (including consultation, diagnosis, tests, and medicine). Household expenditure is used as a proxy for income because income is not reliable in many African settings. Per capita household expenditure, computed by dividing each household’s total expenditure by their total household size, was used for the assessment of impoverishment.

Analysis of the impoverishing impact of out-of-pocket health spending

Impoverishing impact of OOP health spending is estimated at the individual level by comparing poverty levels before (pre-payment) and after (post-payment) OOP health spending. Three measures of poverty are estimated: poverty headcount ratio, poverty gap, and the normalised poverty gap. These indices are estimated using both prepayment and post-payment per capita expenditure. Prepayment expenditure represents the household budget before paying OOP for health services, while post-payment expenditure is prepayment expenditure net of OOP health spending. The poverty headcount index measures the proportion of individuals with per capita consumption expenditure (pre- or post-payment) below the poverty line [20].

As outlined elsewhere [21], if \( {P}_i^{pre} \) is the prepayment poverty indicator, such that \( {P}_i^{pre}=1\left({y}_i< PL\right) \), it means that an individual i is poor if yi < PL . Here, yi is the individual’s per capita prepayment expenditure and PL is the poverty line.

The pre-payment poverty headcount ratio (\( {H}_{pov}^{pre} \)) is given as:

where N is to total sample size. Further, if we define \( {g}_i^{pre} \) as the deficit from the poverty line such that:

Then the prepayment poverty gap measure (\( {G}_{pov}^{pre} \)) that aggregates the deficit of household per capita expenditures from the poverty line is given as:

The prepayment poverty gap normalised by the poverty line (\( {NG}_{pov}^{pre} \)) is given as:

The normalised poverty gap is useful to compare poverty levels between countries with different currencies and poverty lines [22].

The post-payment poverty indices \( \left({H}_{pov}^{post},{G}_{pov}^{post},{NG}_{pov}^{post}\right) \) are obtained analogously by replacing the prepayment expenditure by post-payment expenditure.

The difference between the post-payment and prepayment poverty indices provides the poverty impact of OOP payments. For example, the impact of OOP health expenditures on the poverty headcount is \( \left({H}_{pov}^{post}-{H}_{pov}^{pre}\right) \). Two poverty lines were used in this paper—the US$1.90/day international poverty line at the 2011 purchasing power parity (PPP) [23] and the national poverty line (Birr 3781 per person per year [24]); which is equivalent to US$2.10/day in 2011 prices.

The probit regression was used to assess the factors associated with impoverishment headcount based on the national poverty line. The dependent variable in the probit regression is a binary indicator that takes on the value of one for impoverishment from OOP health spending and zero, otherwise. The explanatory variables in the model included household-level factors selected based on literature and availability in the dataset [25]. Factors related to household head are age, gender, education, marital status, and whether the household head engaged in any productive work. Other household-level covariates include household size, availability of under-five children, availability of adults aged at least 65 years, and the ecology of residential areas (highland, moderate, lowland, urban).

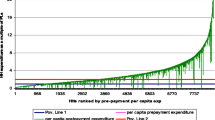

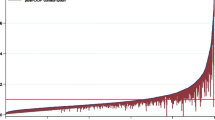

The “Pen’s parade of dwarfs and a few giants” was used to depict the impoverishing effect of OOP health spending [22]. Here, prepayment consumption expenditure is graphed against post-payment consumption expenditure, with individuals ordered according to prepayment consumption expenditure. Stata 15 [26] was used to analyse the data.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Over 60% of the households are in urban areas, with an average of five members per household (Table 1). The average age of the household heads was 42 years. About two-thirds of the households were male-headed. A large proportion of household heads (43.10%) had no formal education. Only about 31.19 and 19.31% attained primary and secondary education levels, respectively. The average annual per capita household consumption expenditure and OOP health spending were Birr 30,088 (US$ 1751.34) and Birr 431 (US$ 25.09), respectively.

Estimates of impoverishment

The national poverty headcount ratio increased by 1.19% points due to OOP health spending, using the Ethiopian national poverty line of US$2.10/day (Table 2). At the same poverty line, the normalised poverty gap rose by 0.60% points, representing a 4.51% point relative increase. The impoverishing effect of OOP health spending was very similar, albeit lower, using the US$1.90/day international poverty line. For example, poverty headcount increased by 1.18% points, while the average normalised poverty gap increased by less than 0.01% points.

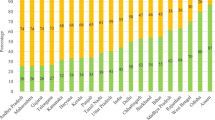

The analysis of medical impoverishment by regions, using the national poverty line, shows that Harrari, SNNP, and Somali regions have very high rates of impoverishment due to OOP health spending with 2.35, 1.66, and 1.36 percentage point increases in the fraction of people pushed into poverty, respectively. Impoverishment in Addis Ababa was the least, with only about 0.35% of the population pushed into poverty by OOP health spending. However, the absolute depth of the rise in poverty was higher for SNNP, Oromia, and Afar where the normalised poverty gaps increased by 0.71, 0.68, 0.58 percentage points, respectively. In terms of residential areas, the rise in poverty levels and absolute intensity of poverty was higher in rural than in urban areas. The poverty headcount ratio rose by 1.31 (rural) and 0.60 (urban) percentage points due to OOP health payments while the increases in the normalised poverty gaps were 0.69 and 0.21 percentage points, respectively. Although the rise in headcount ratio was higher for female-headed than male-headed households, the rise in absolute normalised poverty gaps was larger for male-headed households (Table 3).

The results of the probit regression model show that living in a rural area is the main predictor of impoverishment from OOP health spending. The probability of impoverishment increases by 30.6, 34.1, and 33.6 percentage points for people in highland, moderate, and lowland rural areas, respectively, as compared to those in urban areas. Households with at least one under 5-year-old child (12.9% points) and larger households (4.9% points) also have a significantly higher probability of experiencing impoverishing OOP health spending compared to their counterparts. The probability of impoverishing OOP health spending reduces by 10.2% points in households headed by an individual with formal education compared to those headed by an individual with no formal education. Although male-headed households have a reduced likelihood of experiencing impoverishing OOP health payments, this is only marginally significant (Table 4).

Figure 1 depicts the impoverishing effect of OOP health spending using the Pen’s parade. This figure shows that some non-poor individuals are dipped into poverty while many already poor individuals became further impoverished by OOP health spending in Ethiopia.

Discussion

This study presented an analysis of the impoverishing effect of OOP health spending and factors associated with impoverishing OOP health spending in Ethiopia. In 2011, between 1.18 and 1.19% of the total population were forced into poverty in Ethiopia due to OOP health spending. When extrapolated at the national level based on population projection for 2011 [27], this represents over 957,100 individuals impoverished by OOP health spending. Also, the average poverty gap has deepened for those who were already below the poverty line before paying OOP for health services. Harari, SNNP, Somali, and Amhara regions had higher incidences of impoverishment due to OOP health spending, which is higher than the national average. However, SNNP, Oromia, and Afar had a more substantial rise in the depth of poverty, part of which is due to people who were already in poverty being pushed further into poverty. Similarly, rural residents and female-headed households had a higher proportion of individuals that were pushed below the national poverty line compared to their counterparts. It is important to note that the proportion of people living below the national poverty line before deducting OOP health spending (37%) is seven percentage points higher than the World Bank’s estimate (30%). Also, pre-payment poverty rates for the regions were also estimated at higher ratios [24]. These disparities may be due to the difference in data sources. Nevertheless, these estimates show that about a third of the Ethiopian population is living below the national poverty line.

The results of this paper are not directly comparable with other studies due to differences in methodology, poverty lines, and/or data. Nevertheless, the results appear similar to those from some studies. A recent international study showed that impoverishment resulting from OOP health spending ranged between 1% point and 4% points [3]. An earlier study using the 2004 data showed that OOP health spending impoverished less than 1% of the Ethiopian population [17]. While that study used older data, the more recent (2010/11) HCES dataset shows that impoverishment from OOP health spending in Ethiopia is as high as 1.19% points. Other studies in Africa found a similar pattern of impoverishment from OOP health spending [28,29,30,31,32]. For example, in Ghana, J Akazili, JE-O Ataguba, EW Kanmiki, J Gyapong, O Sankoh, A Oduro and D McIntyre [31] report that between 1.6% points and 1.8% points of the Ghanaian population were impoverished by OOP health spending in 2005/06. In eSwatini, this was estimated to be between 1.0 and 1.6% of the Swazi population in 2009/10 [32]. B Kwesiga, CM Zikusooka and JE Ataguba [30] found that as high as 4% of the Ugandan population was impoverished by OOP health spending in 2009/10.

The impoverishing effect of OOP spending in Ethiopia suggests that policies such as the fee waiver and health insurance schemes [33] have not led to reductions in the incidence of impoverishment from paying OOP for health services. Fee waiver beneficiaries still report under-utilisation and other barriers to seeking health services [34]. Although introduced since 2003/04, the new fee-waiver system was not fully operational nationally in 2011 with only about 6% of people living below the poverty line screened [34]. Based on the 2011 Ethiopian population, these were only about 1.8 million people [27]. All things being equal, any individual from the remaining population living below the poverty line (22.9 million) would be pushed further into poverty as a result of OOP health spending, if health services are needed. Fee-waiver does not also necessarily provide the safety net it is supposed to. It was revealed that fee waiver beneficiaries pay for healthcare despite being entitled to free care due to perceived poor quality of free services, unavailability of drugs and diagnostic procedures, and to avoid the social stigma of being labelled the poorest [35]. Previous studies also show that fee-waiver and exemption systems are ineffective in providing financial protection to the poor [33, 36, 37]. It should also be noted that the fee-waiver system does not cover non-medical costs of care-seeking (e.g. transportation, food, and accommodation), and the opportunity cost of care-seeking. These costs can be substantial and can increase the burden of healthcare payments [38]. Thus, impoverishing healthcare payments may lead to forgoing needed healthcare services, which further aggravates health problems. Households may also resort to coping strategies such as borrowing, distress sale of assets, and reducing consumption of necessities [39]. Therefore, OOP health spending is a barrier to achieving not only the health-related SDGs but also the other goals such as ending poverty, hunger, and food insecurity by trapping people in the vicious cycle of poverty [4].

Similar to people below the poverty line who are pushed deeper into poverty due to OOP health spending, the burden faced by other populations – especially those near poor – should also be appreciated. Households who are not entitled to fee-waiver or covered by health insurance and are closer to the poverty line can easily fall into poverty if they incur OOP healthcare costs. Therefore, they would also be either ignoring healthcare needs or using similar coping strategies to reduce healthcare payments and thereby avoid poverty. This study showed that the risk of impoverishment is higher for rural residents than for urban residents. This can be explained by the interrelated factors of the higher burden of disease in rural areas coupled with inadequate means for paying for healthcare services due to subsistence living [40,41,42]. Sub-populations that are vulnerable to impoverishment from OOP health spending include households with many dependents (either large household size) and/or households with under-five children. Under-five children may need more healthcare services, which increase OOP health spending [43]. Among household characteristics that are associated with a lower probability of impoverishment are living in households headed by a male and/or educated persons. Other studies from China, India, Nigeria, and Vietnam [44,45,46,47] reported similar results. This is an indication of gender-based differences in the burden and impact of OOP health spending to the disadvantage of women. This also highlights the importance of the social determinants of health in influencing healthcare need and thereby OOP health spending and impoverishment. Based on this study, age and having older people in a household were not related to impoverishment. However, K Koch, C Pedraza and A Schmid [46] and S Ahmed, S Szabo and K Nilsen [47] found that having older adults and a household headed by older persons increase the likelihood of impoverishment from OOP health spending. It remains unclear why these variables were not significant in the Ethiopian case.

Although the Ethiopian health insurance reforms were at their early stages when the data used for this study were collected, a study that evaluated the CBHI pilot programmes provides some insights on the affordability of the schemes. The evaluation showed that although premiums were subsidised, especially for the poorest of the poor, 39% of non-CBHI members indicated the unaffordability of premium as a barrier to enrolment. Premiums were also unaffordable for about 16% of CBHI members [34]. In fact, between 2012 and 2013, more than a quarter (26%) of households in the pilot districts, mainly those in the lowest income quintile, dropped out of CBHI schemes because they could not afford to pay the monthly premiums [48]. Thus, the estimated impoverishing impact of OOP health spending reported in this paper may be an underestimation [36].

Although this study used the 2011 data, the latest HCES data that were available at the time of the study, the results reported in this paper are very likely not to have changed significantly as OOP payments remained high in 2016; accounting for 37% of current health expenditure [49]. Based on the results of this paper, there is a need for the government of Ethiopia to aim to reduce the share of OOP health spending in overall health financing in the country. This reduction is achievable through a well-functioning pre-payment system for health services. If there is no reduction in OOP health spending, all things being equal, more than 1.2 million people will be pushed into poverty in 2020 based on poverty headcount estimates of this study and population projections for 2020 [27]. Thus, prepayment systems need to be expanded urgently. Lessons from the CBHI pilot and other health financing reforms could be used to design prepayment systems that guarantee access to affordable and effective health services for all in Ethiopia. One challenge for providing adequate financial protection in Ethiopia is the large share (> 80%) of the population engaged in either rural agrarian activities or the informal sector [41, 50]. This notwithstanding, Ethiopia can consolidate on the already declining share of OOP health spending in current health financing and the SHI framework to ensure that financial protection is realised, especially for low-income households and those that are unable to afford health services through an effective cross-subsidisation mechanism. The strength of this paper is the use of a nationally representative and the latest available HCES data. The study also presents a comparative analysis of poverty levels using both international and national poverty lines. There are also a few limitations. OOP data may have been under-reported since health expenditure was aggregated at the household level and due to recall bias. The survey also excluded those who did not seek needed health care due to unaffordability. Thus, impoverishment resulting from OOP health spending may have been under-estimated.

Conclusion

This study shows that a significant number of the population in Ethiopia is impoverished by paying OOP for health services. Generally, OOP health spending impoverishes the population by either pushing the non-poor below the poverty line or deepening poverty levels of the poor. Recent reforms such as the fee waiver and CBHI scheme seem to have contributed minimally to increasing financial protection in the country. Thus, households who were already below the poverty line and who needed health care have to bear further impoverishment or forgo healthcare services. The Ethiopian government needs to do more to address the challenges, especially for the poor and those who are unable to afford health services. Government actions may include, among other things, scaling up the uptake of health insurance and ensuring universal health coverage for all in Ethiopia. Where possible, the large informal sector may suggest that an alternative non-contributory prepayment system may be significant in providing financial protection for all in Ethiopia.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed for this study can be obtained from the Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency.

Notes

The Global Health Expenditure dataset estimates OOP payments at 47% of current health expenditure in 2011. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/ViewData/Indicators/en

Abbreviations

- CBHI:

-

Community-based health insurance

- EA:

-

Enumeration areas

- FDRE:

-

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

- HCES:

-

Household consumption and expenditure survey

- OOP:

-

Out-of-pocket

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable development goals

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

SDSN. Health in the framework of sustainable development: technical report for the Post-2015 development agenda. New York: Thematic Group on Health for All of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network; 2014.

Kieny MP, Bekedam H, Dovlo D, Fitzgerald J, Habicht J, Harrison G, Kluge H, Lin V, Menabde N, Mirza Z, et al. Strengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable development. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(7):537–9.

Wagstaff A, Flores G, Smitz M-F, Hsu J, Chepynoga K, Eozenou P. Progress on impoverishing health spending in 122 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e180-92.

United Nations: The sustainable development goals report. 2017.

World Health Organization. Global health expenditure database. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

McIntyre D, Kutzin J. Health financing country diagnostic: a foundation for national strategy development (health financing guidance no.1). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

van Doorslaer E, O’Donnell O, Rannan-Eliya RP, Somanathan A, Adhikari SR, Garg CC, Harbianto D, Herrin AN, Huq MN, Ibragimova S, et al. Effect of payments for health care on poverty estimates in 11 countries in Asia: an analysis of household survey data. Lancet. 2006;368:1357–64.

WHO. Health Systems Financing: the path to universal coverage. In: The world health report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

MOH. Ethiopia’s Fifth National Health Accounts 2010/2011. Addis Ababa. Federal Ministry of Health; 2014.

MOH. Health and health related indicators. Addis Ababa. Federal Ministry of Health; 2015.

MOH. Healthcare financing strategy. Addis Ababa: The Federal Ministry of Health; 1998.

MOH. Ethiopia’s second national health accounts. Addis Ababa: Health Care Financing Secretariat; 2003.

MOH. Estimating willingness to pay for health care in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health; 2001.

MOH. Social health insurance strategy. Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health; 2008.

House of Peoples Representatives of Ethiopia. Proclamation no. 690/2010: Social Health Insurance Proclamation. Addis Ababa: Federal Negarit Gazeta of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; 2010. p. 5494.

Abt Associates Inc. Health financing reform in Ethiopia: results and progress to data. Addis Ababa: Abt Associates Inc; 2013.

World Health Organization, World Bank. Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2017 global monitoring report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

Hailemichael Y, Hanlon C, Tirfessa K, Docrat S, Alem A, Medhin G, Lund C, Chisholm D, Fekadu A, Halemariam D. Catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment in households of persons with depression: a cross sectional, comparative study in rural Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:930.

CSA. The 2010/11 Ethiopian household consumption expenditure (HCE) survey. Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Agency; 2012.

Haughton J, Khandker SR. Handbook on poverty and inequality. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank; 2009.

Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: with applications to Vietnam 1993-98. Health Econ. 2003;12(11):921–33.

O’Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington DC: World Bank; 2008.

Ferreira FHG, Chen S, Dabalen A, Dikhanov Y, Hamadeh N, Jolliffe D, Narayan A, Prydz EB, Revenga A, Sangraula P, et al. A global count of the extreme poor in 2012: data issues, methodology and initial results. IZA Discussion Paper No 9442. Germany: Institute for the Study of Labour; 2015.

World Bank. Ethiopia: poverty assessment: New York: World Bank Group; 2015.

Li Y, Wu Q, Xu L, Legge D, Hao Y, Gao L, Ning N, Wan G. Factors affecting catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment from medical expenses in China: policy implications of universal health insurance. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(6):664–71.

StataCorp. Stata: release 15 - Statistical software. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2017.

CSA. Population projections of Ethiopia (2007–2037). Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Agency; 2013.

Barasa EW, Maina T, Ravishankar N. Assessing the impoverishing effects, and factors associated with the incidence of catastrophic healthcare payments in Kenya. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:31.

Mchenga M, Chirwa GC, Chiwaula LS. Impoverishing effects of catastrophic health expenditure in Malawi. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:25.

Kwesiga B, Zikusooka CM, Ataguba JE. Assessing catastrophic and impoverishing effects of healthcare payments in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:30.

Akazili J, Ataguba JE-O, Kanmiki EW, Gyapong J, Sankoh O, Oduro A, McIntyre D. Assessing the impoverishment effects of out-of-pocket healthcare payments prior to the uptake of the national health insurance scheme in Ghana. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2017;17(1):13.

Ngcamphalala C, Ataguba JE. An assessment of financial catastrophe and impoverishment from out-of-pocket health care payments in Swaziland. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1428473.

MOH. Targeting health service in Ethiopia: a proposal for improving fee waiver and exemption systems. Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health; 2003.

Alebachew A, Yusuf Y, Mann C, Berman P. Ethiopia’s progress in health financing and the contribution of the 1998 healthcare and financing strategy in Ethiopia: Boston: Harvard School of Public Health; 2015.

Chote T, Tushune K, Yitbarek K, Woldie M. The utilization of health services among poor households with user fee payment waiver certificate in Gamo Gofa zone, southern Ethiopia. Divers Equality Health Care. 2017;14(5):243–8.

McIntyre D, Thiede M, Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. What are the economic consequences for households of illness and paying for healthcare in low- and middle-income country contexts? Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:858–65.

Gilson L. The lessons of user fee experience in Africa. Health Policy Plan. 1997;12(4):273–85.

Guda A, Akalu T, Melesse T, Hailemariam D. Disparity of out-of-pocket payments on reproductive health related disorders across gender and life course. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2012;26(1):258–64.

Leive A, Xu K. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:849–56.

Admassie A, Abebaw D. Rural poverty and marginalization in Ethiopia: a review of development interventions. In: von Braun J, Dordrecht GF, editors. Marginality: Dordrecht Heidelberg, New York, London: Springer; 2014.

CSA. Demographic and health survey of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Agency; 2016.

CSA. Ethiopia: demographic and health survey. Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Agency; 2012.

Takele K, Zewotir T, Ndanguza D. Risk factors of morbidity among children under age five in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:942.

Kumar K, Singh A, Kumar S, Ram F, Singh A, Ram U, Negin J, Kowal PR. Socio-economic differentials in impoverishment effects of out-of-pocket health expenditure in China and India: evidence from WHO SAGE. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135051.

Aregbeshola BS, Khan SM. Determinants of impoverishment due to out-of-pocket payments in Nigeria. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2017;29(2):194–9.

Koch K, Pedraza C, Schmid A. Out-of-pocket expenditure and financial protection in the Chilean health care system - a systematic review. Health Policy. 2017;121:481–94.

Ahmed S, Szabo S, Nilsen K. Catastrophic healthcare expenditure and impoverishment in tropical deltas: evidence from the Mekong Delta region. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:53.

Mebratie AD, Sparrow R, Yilma Z, Alemu G, Bedi AS. Dropping out of Ethiopia’s community-based health insurance scheme. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30:1296–306.

World Health Organization: Global Health Expenditure Database. In: Geneva: World Health Organization n.d.

CSA. Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census. Addis Ababa: United Nations Population Fund; 2008. https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en.

Acknowledgements

JEA is supported by the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation.

Funding

This work was supported through the National Research Foundation (Grant number: 64800).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AGO: Study conceptualisation and design; data acquisition and analysis; data interpretation; writing; revising and approving the final draft. JEA: Study conceptualisation and design; data analysis; data interpretation; writing; revising and approving the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As we are carrying out secondary data analysis, ethics and consent are not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:

Table 3. The impoverishing effect of OOP health spending by region in Ethiopia, 2010/11. Table 4: The impoverishing effect of OOP health spending by residential areas and gender in Ethiopia 2010/11.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Obse, A.G., Ataguba, J.E. Assessing medical impoverishment and associated factors in health care in Ethiopia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 20, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-020-00227-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-020-00227-x