Abstract

Background

Access to and delivery of comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care (CEmONC) services are often weak in low and middle-income countries affecting maternal and infant health outcomes. There are no studies on resources for maternal healthcare in the Northern region of Ghana. This knowledge is vital for health service planning and mobilising funding to address identified gaps. We investigated the available resources for managing CEmONC and referral services in the region.

Methods

This study involved a cross-sectional survey of maternity facilities in ten hospitals in the Northern region of Ghana, serving a population of 2,479,461, including 582,897 women aged 15–49. Public and faith-based hospitals were included in the study. We used the Service Provision Assessment tool to gather data for this study between October and December 2019. Given the small sample size, we used descriptive statistics to summarise the data using SPSS version 25 and Excel 2016.

Results

A total of 22,271 ANC visits from women to these hospitals occurred in the past 3 months preceding the study; however, 6072 birth events (cases) occurred within the same period. All the hospitals had less than one general medical doctor per 10,000 population (range 0.02–0.30). The number of midwives per 10,000 population ranged from 0.00 (facility H and J) to 1.87 (facility E), and none of the hospitals had a university-trained nurse designated for maternity care. Only one hospital had complete equipment for emergency obstetric and newborn care, while four others had adequate emergency obstetric care equipment. The number of maternity and delivery beds per 10,000 population was low, ranging from 0.40 to 2.13.

Conclusions

The management of emergency obstetric care and referrals are likely to be affected by the limited human resources and equipment in hospitals in Northern Ghana. Financial and non-financial incentives to entice midwives, obstetricians and medical officers to the Northern region should be implemented. Resources should be mobilised to improve the availability of essential equipment such as vacuum extractors and reliable ambulances to enhance referral services. Considerable health system strengthening efforts are required to achieve the required standards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A successful health system is the one that links people to the required level of care so that they receive prompt care in a timely fashion [1]. Research examining referral systems in low and middle-income countries has found that the quality of and access to emergency healthcare are influenced by geography, the distribution, and location of health facilities, communication, socio-demographic and cultural dynamics [2,3,4]. Access to Basic and Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (BEmONC, CEmONC) is an essential strategy for averting maternal and neonatal mortality [4] and is reliant on a well-coordinated referral system [5, 6]. The availability and quality of EmONC services in low and middle-income countries are limited and have been attributed to problems with referral systems [7,8,9]. Service Provision Assessments (SPA) across low and middle income countries have identified critical gaps. For example, an assessment of health facilities in Tanzania revealed that they were less likely to have an emergency transportation system (10%) [10]. In Kenya, an SPA found that, health facilities generally performed well, however, private facilities were more accessible [11].

The third Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) urges all countries to institute measures that can reduce maternal deaths below a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030. This SDG calls on countries to reduce newborn deaths to 12 deaths per 1000 live births within the same period [12]. As of 2017, Ghana’s MMR was 310 deaths per 100,000 while neonatal mortality rate (NMR) stood at 25 per 1000 live births [13].

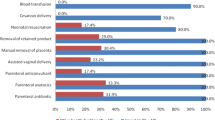

More concerted efforts are required to achieve high-quality maternal healthcare and ensure better inter-facility linkages. Essential interventions or signal functions are needed to treat serious obstetric complications that contribute to reducing maternal mortality and preventing adverse birth outcomes [14]. The availability of the signal functions corresponds to the level of emergency obstetric and newborn care of facilities where these are provided [14]. At the first level of care, BEmONC comprises parenteral antibiotic administration, uterotonic drugs administration, administration of parenteral anticonvulsants for preeclampsia and eclampsia, manual removal of placenta, removal of retained products, performing assisted vaginal delivery, and performing basic neonatal resuscitation; at the referral level of care, CEmONC includes performing caesarean-section surgery and blood transfusion in addition to the seven BEmONC interventions [14]. Furthermore, WHO recommends a ratio of 2.28 midwives/doctors per 1000 population [15, 16]. Therefore, maternal complications can be effectively managed if health facilities are equipped and staffed optimally [17].

Since independence in 1957, the Northern region of Ghana has experienced an inequitable distribution of health workers and other essential resources [18]. The harsh climatic and high levels of poverty in the region contribute to its disadvantaged status [19]. The southern region of Ghana in comparison, has a more highly developed infrastructure and accommodates the head offices of central Government ministries and businesses. Between 1991 and 2006 poverty declined in the south by 58.7%, while in the northern region only experienced a 8.9% reduction in poverty during this period [18].

The Northern region, has 10.2% of the nation’s population, but only 2% (38) of the country’s medical officers and 7.4% (285) of midwives. The southern region of Volta in comparison has 8.6% of Ghana’s population while it has 2.7% (43) of the nation’s medical officers and 10.1% (386) of all midwives. Similar trends exist in the distribution of health staff in other categories [20]. Successive governments have tried to incentivize the health workforce to accept postings to the Northern region. Among these measures are the Deprived Area Incentive Scheme, where a 20–35% allowance and basic salary are provided tor those who accept a posting to the region coupled with housing [21].

However, these incentives have not resulted in a change in workforce distributions. In 2016, the Greater Accra and Northern region had doctor-patient ratios of 1:3136 and 1:18,380, respectively [22]. An ambulance audit in 2018 also revealed that the Northern region had six of the 55 functional ambulances available for use in the country [23]. In contrast, the Central region had nine of these ambulances to serve 9.2% of the nation’s population. This has necessitated the use of donkeys and tricycles for some maternal referrals in the Northern region [24]. The absence of transport has been linked to an increase in perinatal death [25] and home delivery [26] in several African countries.

The lack of transport can significantly compromise the ability of CEmONC level health facilities to function optimally. Studies of Emergency Obstetric Care (EmOC) services in the Upper East region of Ghana found limited availability of transport, equipment and supplies for maternity care [27]. A range of factors such as inadequate medical supplies, drugs, poor referral processes and a lack of reliable communication was found to compromise women’s access to essential maternal health services [27, 28]. There are no studies that examine the available resources for maternal healthcare in the Northern region of Ghana and the management of maternal referrals within the region. Therefore, we sought to investigate the availability of resources for managing maternity conditions and how maternal referral services are handled and delivered in this region. These findings provide a useful baseline for decision-makers regarding the resources required to improve maternal health care.

Theoretical framework

This study is underpinned by functionalist theory [29, 30] that argues that the ability of social institutions, such as health facilities, to address human needs justifies their existence. Each institution influences the form, shape and sustainability of society by providing their core duties. Consequently, the institutions’ inability to offer such roles would render them obsolete [29, 30]. The terms ‘functional’ and ‘dysfunctional’ describe the impact of institutions on society. For instance, a hospital is deemed functional if it has all the necessary resources and executes its role accordingly, contrarily, it is dysfunctional if it operates below its required mandate [29, 30].

It is noteworthy that a health facility can be functional and dysfunctional simultaneously. For hospitals to provide optimum maternity healthcare and well streamlined maternal referral, the health facility must be functional. A functional healthcare provider is a provider who identifies signal function(s), act professionally, and refer cases in line with recommended guidelines.

Methods

Study design

This study used a cross-sectional survey in ten hospitals in the Northern region of Ghana to assess the available resources for maternity healthcare including CEmONC and emergency referral. The hospitals comprised all the nine district hospitals in the region; consisting of public (2) and faith-based private-public (7) district hospitals as well as the regional hospital (1). This is the definition of the Ghana Health Service and WHO [22, 31, 32].

Definitions

Maternity beds refer to all beds available for all maternity or labour related conditions including beds for resting while in labour, beds for childbirth and those used during the immediate postpartum period prior to discharge. On the other hand, delivery beds refer to beds that are exclusively designated for actual childbirth alone.

Study setting

The Northern region of Ghana is divided into the district, municipal or metropolitan local government areas. The metropolitan area has approximately 250,000 people; a municipality has at least 95,000 people while a district has approximately 75,000 people [33]. For the purpose of this study, the “district” denotes all the three local government areas. There are nine district hospitals across the 16 districts of the region. This study involved all the nine district hospitals and the regional hospital.

Data collection instrument

We used the Service Provision Assessment (SPA) tool to gather data for this study. The tool has been uploaded as Additional File 1. The SPA was developed by the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) Program for assessing health facilities in developing countries [34]. The assessment is carried out with a questionnaire that includes questions on facility level infrastructure, resources and systems, maternal and child health services, family planning and sexually transmitted infections [34]. The tool is suitable for assessing maternal and newborn healthcare, child healthcare, infrastructure, resources, systems, and family planning service provision. In 2002, the SPA was used to assess health service delivery in Ghana. It has also been used extensively in other Sub-Saharan Africa countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Kenya and Malawi [34]. For this study, we revised the tool to fit the characteristics of the northern region’s health facilities. For instance, the tool aggregates responses when assessing the number of equipment, such as beds. However, most of the facilities assessed had few beds (e.g. 70% had less than five delivery beds), so we reported the actual beds per facility instead of categorising or grouping the number of beds.

Data collection

Prior to data collection, invitation letters explaining the study’s purpose were sent from the Northern regional health directorate to Medical Superintendents of the nine district hospitals and the regional hospital selected. All heads of the hospital maternal health services were pre-informed by the Medical Superintendents. Following introductions and explanation of the study, we followed up to seek their interest and availability, obtain written informed consent, and schedule appointments with them. We interviewed the heads of maternity health services of the hospitals; however, their assistants were interviewed when it was not possible to meet them in person. Reported figures (e.g. number of ANC visits and number of births) were verified from the records of each facility to ensure accuracy.

All interviews took place at the hospitals during regular working hours. Midwives, all medical officers and midwives in Ghana obtain formal training on EmONC (e.g. caesarean section, vacuum aspiration, blood transfusion, assisted deliveries) as part of their formal training and are also guided by the Safe Motherhood Protocol of Ghana Health Service which dictates how to handle maternity conditions [35]. Data collection was undertaken by two authors (EKA and RMA). EKA is a social scientist public health researcher with much experience in survey administration. RMA is a clinical midwife with expertise in assessing maternity healthcare who clarified the terminology and fieldwork procedures. Interviews lasted between 25 and 40 min. Data collection took place between October 2019 and February 2020.

Data analysis

Our unit of analysis was at the facility level. We used SPSS version 25 and Excel 2016 for analyses. Given the minimal sample size, we used descriptive statistics to summarise the various aspects of the data. The results are presented in frequencies and percentages. In order to make the findings comparable to global standards as recommended by the WHO [15, 36], in each district/region, we computed the total number of births and ANC attendance within the 3 months preceding the survey per 100,000 (Table 1), maternal healthcare staff per 10,000 (Table 2), and the number of available beds (maternity and delivery beds) per 10,000 (Table 3). Finally, we summarised the available signal functions and essential equipment for maternity healthcare (Table 4).

Ethical approval

The study protocol was assessed, approved, and ratified by the Navrongo Health Research Centre of the Ghana Health Service [NHRCIRB347]; and the Human Research Ethics Review Committee of the University of Technology Sydney, Australia [ETH19–4201]. Each participant provided written consent to participate in the study and to publish the data in a form that does not identify them in any way. All hospitals were de-identified and assigned identification letters.

Results

Births and ANC attendance

A total of 22,271 ANC visits from women to these hospitals occurred in the ten hospitals in the past 3 months preceding the study; however, 6072 birth events (cases) occurred within the same period. The number of ANC visits within the period ranged from 467 (facility E) to 7184 (facility A), with a ratio per 100,000 ranging between 289.74 (facility A) and 1858.08 (facility B). For the whole region, there were 577.98 ANC visits per 100,000 population. The number of births ranged from 161 (facility I) to 1400 (facility B) with a ratio per 100,000 ranging between 45.01 (facility A) and 608.83 (facility E). For the entire region, there were 157.58 births per 100,000 as indicated in Table 1.

Maternal healthcare staff at the hospitals

There were 280 healthcare providers designated for maternity care within the region and ranged from no specialists and no university-trained nurses to 149 midwives. Across facilities, this ranged from 0 specialists/university-trained nurses (in all facilities) to 67 midwives in facility B. For the whole region, healthcare provider per 10,000 population ranged from 0 healthcare provider (specialists/university-trained nurses) per 10,000 population to 0.39 healthcare providers per 10,000 population (midwives).

Maternity beds and partographs

The number of maternity beds per facility ranged from 2 (facility B) to 36 (facility A) with a ratio per 10,000 ranging between 0.05 (facility B) and 2.13 (facility I). For the whole region, there were a total of 163 beds with a ratio of 0.42 per 10,000. The number of maternity beds per facility ranged from 1 (facility F) to 6 (facility A) with a ratio per 10,000 ranging between 0.02 (facility A) and 0.40 (facility D). For the entire region, there were a total of 32 beds with a ratio of 0.08 per 10,000. All the ten hospitals reported that they used the partograph to monitor labour. However, six use partograph for all cases while four use partograph for some selected cases or conditions (data not shown).

Availability of CEmONC and equipment for maternal healthcare including referral

Six hospitals had functional ambulances stationed on their premises, three (E, F, G) had cellular phones and seven were having access to email/internet. Four out of the ten hospitals had signal functions for BEmONC (A, E, F, J). However, only hospital A had all the signal functions for CEmONC. Hospital I had the least signal functions for CEmONC (i.e. four). All the hospitals had stethoscope, blood pressure cuffs and fetoscope except hospital J. Infant scale was available in all the hospitals; however, only four (A, C, D, H) had incubators.

Guidelines/standards for the delivery, emergency care and referral

The respondents in all ten hospitals reported that they had guidelines or standards for delivery/emergency obstetric care. We sighted the guidelines in eight hospitals. Eight hospitals were using the Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth (IMPAC) guidelines and the National Guidelines for CEmOC. One hospital had a national guideline called Safe Motherhood protocol.

Five of the hospitals had guidelines for maternal referrals. Of these five hospitals, we sighted guidelines in two hospitals that had been adapted from the national referral policy and guidelines developed to fit their local context. These locally developed guidelines considered the distance and time spent when referring women to the regional hospital, which happens to be the destination of most referral cases. All the hospitals indicated that they have hospital referral forms; however, we saw these in nine hospitals.

Key informants of all ten hospitals reported that referral forms accompany all cases to the receiving hospital. Nine of the hospitals reported that they keep copies of the completed referred forms. When we assessed the individual items on the referral forms against the ones outlined by Ghana’s National Referral Policy and Guidelines, the ‘urgency of referral condition’ was not included on the referral forms used by hospitals A and I.

Discussion

This study used the functionalist perspective to assess the capacity for maternal healthcare provision and maternal referral in the Northern region of Ghana. We found that human resources for maternal healthcare were very low compared with the WHO recommended ratio of doctors, nurses and midwives per 10,000 population [15], while some health staff categories were not available for maternity care. For instance, the hospitals with the highest ratio of doctors (0.30 per 10,000 population), nurses (0.46 per 10,000 population) and midwives (1.76 per 10,000 population) were far below the recommended threshold of 23 per 10, 000. None of the ten hospitals had a university-educated nurse, a specialist doctor, or allied health professionals such as social workers or physiotherapists working within maternal healthcare.

According to the Ghana Health Service and WHO standards, the ten hospitals included in the study are CEmONC level facilities with each serving a population between 75,000 and 250,000 [33]. According to the staffing norms of the Ministry of Health, a regional hospital should have at least 40 midwives [37], yet the regional hospital assessed in our study had only 19 midwives. Six of the district hospitals, also fell below the national level required minimum threshold of 10–84 [37]. The northern region, therefore, has a “critical shortage” of maternity health workers because according to WHO, a “critical shortage” of health workers occurs when less than 23 midwives, nurses and doctors serve a population of 10,000 [15, 16]. This reflects vast gaps between current guidelines and can compromise hospitals’ ability to function [29, 30, 38]. Thus, the shortage can have serious consequences for maternal mortality and morbidity; if more women tend up for care, the health providers may not be able to provide prompt service and the delay can lead to death thereby compromising the functionality of health facilities [3, 29, 30]. Similarly, the critical shortage of human resource for healthcare has been reported from other sub-Saharan African countries such as Mali, Uganda, Sudan and Nigeria [39, 40].

New initiatives need to be instituted to attract and retain maternity care staff especially nurses and midwives to the Northern Region as previous financial interventions such as allowances and accommodation schemes have not attracted adequate numbers [21]. Healthcare trainees from the Northern region may be recruited within the region to reduce the chances of non-indigenous healthcare providers returning to their home regions. Improving the working environment of staff may also be required for these incentives to be successful.

Additionally, ensuring a comfortable living environment of the healthcare providers and their immediate families (e.g. well-ventilated housing with adequate drainage that is close to extended family and quality schooling for children, as well as employment opportunities for spouses) can motivate health workers to remain in the region and provide quality care. A systematic review of maternal health interventions in resource-constrained countries found that interventions aimed at creating a supportive working environment such as revamping existing health facility infrastructure, enhancing drugs supply, consumables and equipment for obstetric care resulted in a 40 and 55% reduction in maternal mortality ratio and case fatality rate respectively [41].

Our study identified gaps in essential equipment and commodities, communication, and transportation for maternity healthcare. Only one hospital had complete CEmONC facilities while only four had facilities for complete CEmOC. Thus, there was a lack of essential equipment needed for triage and care management as specified by WHO, especially for neonatal resuscitation [36, 42]. The inadequacy of essential equipment and commodities for obstetric services has also been reported from Nigeria and Tanzania and could adversely affect healthcare delivery [29, 30, 43, 44]. Greater investment in the equipment for CEmONC is required to ensure the hospitals’ optimal functioning to improve maternal and newborn health within the region.

Hospital I had the highest maternity bed ratio (2.13 per 10,000 population). In comparison, the highest delivery bed ratio of 0.40 per 10,000 population was recorded in hospital D. According to the Ghana Health Service, a standard bed capacity for a district hospital in Ghana ranges between 60 and 120 with at least 11 beds designated for maternity ward [45]. Similarly, a regional hospital should have 150 to 200 beds [46]. Compared with these indicators, two district hospitals and the regional hospital fall short of the required bed capacity. This shortage can have adverse implications on the functionality of these health facilities [29, 30]. A longitudinal study from China indicated that the number of hospital beds per 1000 population is a significant predictor of maternal mortality [47]. Concerted efforts by the government to invest in maternity beds and other essential supplies are vital to improve care and prevent maternal mortality [48, 49].

Our study found that only the regional hospital and five district hospitals had a functional ambulance stationed at their premises. This implies that a greater proportion of women may have transportation challenges during referral and may experience delays in reaching the next facility [3]. This is consistent with evidence from Ethiopia where only 17% of surveyed facilities had dedicated functional ambulances [50]. A facility assessment in Tanzania also revealed that health facilities were less likely to have emergency transportation/ambulance system [10]. The importance of readily available and functional ambulances to improve maternal and newborn health cannot be overemphasised. In India, an average ambulance service intensity (i.e. 0.16 ambulances per million people) resulted in 0.75% (7.5 per 1000) and 1.1% (11 per 1000) probability of reduction in neonatal and infant deaths respectively [51]. This is an indication that reliable ambulance service is critical for healthcare facilities to function optimally [29, 30]. Novel approaches to transporting women to facilities particularly in emergencies are needed. These may include motorized or non-motorized commercial vehicles or vehicles by relatives using private transportation [52].

Only one of the ten hospitals (E) included in our study had a cellular phone available to facilitate maternal referrals. This may suggest the possibility of an inter-facility communication gap during referrals; a situation that does not favour a positive referral outcome (29, 30]. Inter-facility communication is critical for receiving facilities to prepare for the arrival of the woman [53]. The National Referral Policy and Guidelines of Ghana stress that whenever possible, communication with the receiving facility should be made. In addition, all referrals are expected to be accompanied by documentation that conforms to national and internationally acceptable standards [32, 42, 54]. Toll-free communication facilities within hospitals in countries such as in Bangladesh, Uganda, Rwanda has been found to enhance the inter-facility communication required for effective maternal referral [29, 30, 55,56,57].

Ghana’s National Referral Policy and Guidelines state that copies should be available in all units or departments of all hospitals nationwide [54]. Half of the surveyed hospitals in our study reported that they had referral guidelines and only two had readily available copies of the National Referral Policy and Guidelines. While all hospitals reported that they have guidelines or standards for the delivery of emergency obstetric care, copies could only be verified in eight hospitals. This may impact the quality of care and the monitoring of performance to ensure quality improvement. Ensuring the consistent application of guidelines through on-going monitoring may require capacity-building and mobilisation of maternal healthcare providers. The Advance in Labour and Risk Management (ALARM) Program is a well-known initiative that has contributed substantially to improving maternal healthcare quality in several low and middle-income countries through the enhanced monitoring of guideline compliance [58, 59].

The ALARM International Program, developed by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, provides integrated clinically-oriented and evidence-based outreach visits and facility-based maternal death reviews. Program interventions include staff training in obstetric best practice and monthly audit cycles conducted according to WHO guidelines. Greater Criterion-based clinical audit (CBCA) scores were observed in intervention hospitals (68.2%) relative to control hospitals (64.5%) [59]. All these essential inputs can be guaranteed when there is adequate policy-driven healthcare financing by the central government [38] to improve policy management. The implementation of the ALARM program would considerably improve the monitoring of quality care in the Northern Region.

Strengths and limitations

The study has some limitations. The functionalist theory that informed the study does not account for the adverse implications of social disorder, nor did it account for initiatives to improve the status quo. Thus, the theory does not acknowledge uncertainties such as conflicts or mayhem and their implications on healthcare provision and access. The theory is also limited as it does not propose ways to enhance or improve the current health system. This study was carried out in public hospitals and does not include any information about private facilities. However, public hospitals are the key service providers in the Northern Region as they deliver free maternal healthcare under the National Health insurance scheme. The availability of signal functions and some equipment were not observed but ascertained through interviews. Health facilities that provide BEmONC services such as Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS), clinics, polyclinics were also not included since the study’s focus was on CEmONC. Among the strengths of this study are the fact that it assessed all CEmONC services in the Northern region. Two authors with enormous survey administration and maternity healthcare delivery experience in the Ghanaian context gathered the data. Moreover, reported figures were verified from existing records to ensure accuracy.

Conclusion

This study investigated hospitals’ readiness to deliver maternal care and refer women in the Northern region of Ghana. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess maternal services in the region. We identified a number of issues indicating the need for considerable investment to address communication gaps and shortages of essential equipment to improve the efficiency, work safety, and motivation of the maternal health workforce in the region. Comprehensive health systems strengthening is needed at all levels requiring the implementation of current standards for hospitals and strategies such as performance-based financing to enhance the provision of maternal health services in the Northern Region.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALARM:

-

Advance in Labour and Risk Management

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- BEmONC:

-

Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care

- CBCA:

-

Criterion-based clinical audit

- CEmONC:

-

Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care

- CHPS:

-

Community-based Health Planning and Services

- EmOC:

-

Emergency Obstetric Care

- IMPAC:

-

Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth

- MMR:

-

Maternal Mortality Ratio

- SDG:

-

Sustainable Development Goal

- SBM-R:

-

Standards-Based Management and Recognition

- SPA:

-

Service Provision Assessment

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

References

Awoonor-Williams JK, Bailey PE, Yeji F, Adongo AE, Baffoe P, Williams A, et al. Conducting an audit to improve the facilitation of emergency maternal and newborn referral in northern Ghana. Glob Public Health. 2015;10(9):1118–33.

Gething PW, Johnson FA, Frempong-Ainguah F, Nyarko P, Baschieri A, Aboagye P, et al. Geographical access to care at birth in Ghana: a barrier to safe motherhood. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:991.

Thadeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Social Sci Med (1982). 1994;38:1091–110.

Windsma M, Vermeiden T, Braat F, Tsegaye AM, Gaym A, van den Akker T, et al. Emergency obstetric care provision in southern Ethiopia: a facility-based survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018459.

Pattinson R, Kerber K, Buchmann E, Friberg IK, Belizan M, Lansky S, et al. Stillbirths: how can health systems deliver for mothers and babies? Lancet. 2011;377(9777):1610–23.

Tuncalp O, Hindin MJ, Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Adanu RM. Assessment of maternal near-miss and quality of care in a hospital-based study in Accra, Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstetrics. 2013;123(1):58–63.

Akaba GO, Ekele BA. Maternal and fetal outcomes of emergency obstetric referrals to a Nigerian teaching hospital. Trop Dr. 2018;48(2):132–5.

Campbell OM, Calvert C, Testa A, Strehlow M, Benova L, Keyes E, et al. The scale, scope, coverage, and capability of childbirth care. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2193–208.

Mselle LT, Kohi TW. Healthcare access and quality of birth care: narratives of women living with obstetric fistula in rural Tanzania. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):87.

Gupta N, Dal Poz MR. Monitoring health workforce skills mix and productivity to support decision making for health policy and planning: insights from survey data in six low- and middle-income countries. Working paper series, WP-08-107; 2008. USAID & Measure Evaluation.

Lee E, Madhavan S, Bauhoff S. Levels and variations in the quality of facility-based antenatal care in Kenya: evidence from the 2010 service provision assessment. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(6):777–84.

United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development United Nations; 2015. Contract No.: A/RES/70/1.

Ghana Statistical Service, Ghana Health Service, ICF. Ghana Maternal Health Survey 2017. Accra, Ghana; 2018.

WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, AMDD. Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook. Geneva: WHO Press; 2009.

World Health Organization. The world health report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

WHO. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A guide for essential practice. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2015.

UNFPA. Giving birth should not be a matter of life and death giving birth should not be a matter of life and death 2012 [cited 2020 April 10]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/EN-SRH%20fact%20sheet-LifeandDeath.pdf.

Oteng-Ababio M, Mariwah S, Kusi L. Is the underdevelopment of northern Ghana a case of environmental determinism or governance crisis? Ghana J Geography. 2017;9(2):5–39.

Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana poverty mapping report', Series Ghana poverty mapping report. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service; 2015.

Ministry of Health. The Health Sector in Ghana: Facts and Figures 2010. Accra; 2012.

International Organisation for Migration (IOM). National Profile of Migration of Health Professionals– Ghana. 2011.

Ghana Health Service. The health sector in Ghana: facts and figures. Accra; 2016 [Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwi87tDNwJbtAhXNPsAKHXhEBr4QFjACegQIBRAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ghanahealthservice.org%2Fdownloads%2FFACTS_FIGURES_2016.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2nqZRdW61gy2XH4y9YFRqr]. Accessed 23 Oct 2020.

Nunoo F. 29 million Ghanaians dey share 55 ambulances BBC News Pidgin, Ghana2018 [Available from: https://www.bbc.com/pidgin/tori-44030411]. Accessed 23 Oct 2020..

Heyen-Perschon J. Report on current situation in the health sector of Ghana and possible roles for appropriate transport technology and transport related communication interventions. Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, ITDP. 2005.

Jammeh A, Sundby J, Vangen S. Barriers to emergency obstetric care services in perinatal deaths in rural Gambia: a qualitative in-depth interview study. Int Scholarly Res Notices. 2011;2011;1–10.

Scott NA, Henry EG, Kaiser JL, Mataka K, Rockers PC, Fong RM, et al. Factors affecting home delivery among women living in remote areas of rural Zambia: a cross-sectional, mixed-methods analysis. Int J Women's Health. 2018;10:589.

Dalinjong PA, Wang AY, Homer CS. Are health facilities well equipped to provide basic quality childbirth services under the free maternal health policy? Findings from rural northern Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):959.

Kyei-Onanjiri M, Carolan-Olah M, Awoonor-Williams JK, McCann TV. Review of emergency obstetric care interventions in health facilities in the Upper East Region of Ghana: a questionnaire survey. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1);1–8.

Mooney LA, Knox D, Schacht C. Understanding social problems: three main sociological perspectives. East Carolina University, Cengage Learning; 2007.

Merton RK. Social theory and social structure: Simon and Schuster; 1968.

Ghana Health Service. Organisational Structure: Ghana Health Service ICT Department; 2017 [cited 2019 05/09]. Available from: http://www.ghanahealthservice.org/ghs-subcategory.php?cid=2&scid=43.

WHO. WHO Recommended Interventions for Improving Maternal and Newborn Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Institute of Local Government Studies, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. A Guide to District Assemblies in Ghana: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung; 2016.

The DHS Program. Measure DHS Service Provision Assessment Survey: Inventory Questionnaire: MeasureDHS; 2012 [Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/SPA.cfm.

Ghana Health Service. Safe Motherhood Protocol. Accra, Ghana; 2008.

WHO. Global Health Observatory visualisations: indicator metadata registry. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016. Available from https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.wrapper.imr?x-id=97.

Ministry of Health. Staffing norms for the health sector of Ghana: an abridged version. Ministry of Health; 2014.

Mkoka DA, Goicolea I, Kiwara A, Mwangu M, Hurtig A-K. Availability of drugs and medical supplies for emergency obstetric care: experience of health facility managers in a rural district of Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):108.

Willcox ML, Peersman W, Daou P, et al. Human resources for primary health care in sub-Saharan Africa: progress or stagnation? Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:76.

Adeloye D, David RA, Olaogun AA, et al. Health workforce and governance: the crisis in Nigeria. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:32.

Nyamtema AS, Urassa DP, van Roosmalen J. Maternal health interventions in resource limited countries: a systematic review of packages, impacts and factors for change. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):30.

WHO. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016.

Nnebue CC, Ebenebe UE, Adogu PO, Adinma ED, Ifeadike CO, Nwabueze AS. Adequacy of resources for provision of maternal health services at the primary health care level in Nnewi, Nigeria. Nigerian Med J. 2014;55(3):235.

John TW, Mkoka DA, Frumence G, Goicolea I. An account for barriers and strategies in fulfilling women’s right to quality maternal health care: a qualitative study from rural Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):352.

Ghana Health Service. GHS standard hospitals. Accra: Ghana Health Service; 2016.

Ghana Statistical Service Ghana Service Provision Assessment Survey 2002. Ghana Statistical Service; 2003.

Powell-Jackson T, Gao Y, Ronsmans C, Zhou H, Wang Y, Fang H. Health-system determinants of declines in maternal mortality in China between 1996 and 2013: a provincial econometric analysis. Lancet. 2015;386:S15.

Necochea E, Tripathi V, Kim YM, Akram N, Hyjazi Y, da Luz VM, et al. Implementation of the standards-based management and recognition approach to quality improvement in maternal, newborn, and child health programs in low-resource countries. Int J Gynecol Obstetrics Gynecol. 2015;130:S17–24.

Rawlins B, Kim Y-M, Haver J, Rozario A, Kols A, Chiguvare H, et al. Case study: experience applying and tracking a quality improvement approach for maternal and newborn health Services in sub-Saharan Africa. World Health Population. 2015;16(2):31.

Defar A, Getachew T, Gonfa G, Bekele A, Molla M, Alemu K. Low ambulance availability at health facilities and disparity across regions in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional health facility level assessment. Preprint: Research square; 2019.

Babiarz KS, Mahadevan SV, Divi N, Miller G. Ambulance service associated with reduced probabilities of neonatal and infant mortality in two Indian states. Health Aff. 2016;35(10):1774–82.

Kobusingye OC, Hyder AA, Bishai D, Hicks ER, Mock C, Joshipura M. Emergency medical systems in low-and middle-income countries: recommendations for action. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:626–31.

Gitaka J, Natecho A, Mwambeo HM, Gatungu DM, Githanga D, Abuya T. Evaluating quality neonatal care, call Centre service, tele-health and community engagement in reducing newborn morbidity and mortality in Bungoma county, Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):493.

Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health referral policy and guidelines. Accra: Ministry of Health; 2012.

Huq NL, Azmi AJ, Quaiyum MA, Hossain S. Toll free mobile communication: overcoming barriers in maternal and neonatal emergencies in rural Bangladesh. Reprod Health 2014;11(1):1–12.

Ngabo F, Nguimfack J, Nwaigwe F, Mugeni C, Muhoza D, Wilson DR, et al. Designing and implementing an innovative SMS-based alert system (RapidSMS-MCH) to monitor pregnancy and reduce maternal and child deaths in Rwanda. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;1;1–15.

Oyeyemi SO, Wynn R. Giving cell phones to pregnant women and improving services may increase primary health facility utilization: A case-control study of a Nigerian project. Reproductive Health. 2014;11(1).

Lalonde AB, Beaudoin F, Smith J, Plourde S, Perron L. The ALARM international program: a mobilizing and capacity-building tool to reduce maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity worldwide. Obstet Gynaecol Can Nov. 2006;28(11):1004–8.

Pirkle C. Measuring and evaluating quality of care in referral maternities in Mali and Senegal in the context of overlapping interventions; 2013.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Ghana Health Service and the Northern Region Health Directorate of Ghana for the support.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EKA conceived the study and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, RMA contributed to the data collection, drafting of the manuscript and reviewed multiple drafts, CN, NTT, AD supervised the study, reviewed multiple drafts, proposed additions and changes. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was assessed, approved, and ratified by the Navrongo Health Research Centre of the Ghana Health Service [NHRCIRB347]; and the Human Research Ethics Review Committee of the University of Technology Sydney, Australia [ETH19–4201]. Each participant provided written consent to participate in the study and to publish the data in a form that does not identify them in any way. All hospitals were de-identified and assigned identification letters.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ameyaw, E.K., Amoah, R.M., Njue, C. et al. An assessment of hospital maternal health services in northern Ghana: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 20, 1088 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05937-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05937-5