Abstract

Background

High levels of opioid-related mortality, as well as morbidity, contribute to the excessive opioid-related disease burden in North America, induced by high availability of opioids. While correlations between opioid dispensing levels and mortality outcomes are well-established, fewer evidence exists on correlations with morbidity (e.g., hospitalizations).

Methods

We examined possible overtime correlations between medical opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalizations in Canada, by province, 2007–2016. For dispensing, we examined annual volumes of medical opioid dispensing derived from a representative, stratified sample of retail pharmacies across Canada. Raw dispensing information for ‘strong opioids’ was converted into Defined Daily Doses per 1000 population per day (DDD/1000/day). Opioid-related hospitalization rates referred to opioid poisoning-related admissions by province, for fiscal years 2007–08 to 2016–17, drawn from the national Hospital Morbidity Database. We assessed possible correlations between opioid dispensing and hospitalizations by province using the Pearson product moment correlation; correlation values (r) and confidence intervals were reported.

Results

Significant correlations for overtime correlations between population-levels of opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalizations were observed for three provinces: Quebec (r = 0.87, CI: 0.49–0.97; p = 0.002); New Brunswick (r = 0.85;CI: 0.43–0.97; p = 0.004) and Nova Scotia (r = 0.78; CI:0.25–0.95; p = 0.012), with an additional province, Saskatchewan, (r = 0.073; CI:-0.07–0.91;p = 0.073) featuring borderline significance.

Conclusions

The correlations observed further add to evidence on opioid dispensing levels as a systemic driver of population-level harms. Notably, correlations were not identified principally in provinces with reported high contribution levels (> 50%) of illicit opioids to mortality, which are not captured by dispensing data and so may have distorted or concealed potential correlation effects due to contamination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

North America – Canada and the US - has been home to a severe public health crisis of opioid-related (i.e., morbidity and mortality) harms since the early 2000s, initially evolving in contexts of persistently high prescription opioid (PO) availability [1,2,3]. This burden, specifically, has involved excessively high levels of (e.g., overdose) mortality, even negatively affecting general population-based life expectancy in both jurisdictions [4, 5]. Concretely, there were 47,600 opioid-related deaths in the US, and 4100 in Canada, respectively, in 2017, representing similar population-based mortality rates [6, 7].

Most attention regarding acute opioid-related harms has focused on mortality outcomes, as recently further accelerated by widespread proliferation of highly toxic illicit opioid products [6, 8, 9]. Less attention has been given to morbidity outcomes, for example (non-fatal) opioid-related poisonings or disorders. Recent US data have demonstrated rising trends for opioid-related hospitalizations post-2000 [10,11,12]. Opioid-related hospitalizations among public drug plan beneficiaries in Ontario (Canada) increased by 55% from 2003 to 2013 [13].

North American studies have examined associations between population-levels of opioid-dispensing and adverse outcomes towards improved understanding of the systemic drivers of opioid-related harms. While substantive correlations between opioid-dispensing and mortality have been found for several populations and/or jurisdictions [14,15,16], select investigations have established similar correlations for morbidity outcomes. For example, strong associations were found between US-based national prescription volumes of major opioid formulations and related emergency department (ED) visits over a 10-year period (1995–2004 [17];). Moderai et al. established similar correlations for North Carolina (2008–2010); in Florida, associations between PO availability and morbidity were less pronounced than for mortality (2009 [18, 19];). Strong correlations have been ascertained between opioid-dispensing and opioid-related substance treatment admissions in Ontario (2005–2011 [14];). Furthermore, substantial congruence between opioid dispensing and related hospitalizations have been observed for Australian jurisdictions [20, 21].

In Canada, despite overall distinctly high levels of opioid availability, opioid dispensing has considerably varied inter-provincially, with up to 3-fold differences in standardized volumes. Over-time, an inversion trend has been observed: While levels of opioid-dispensing consistently increased until about 2012, some – but not all – provinces have featured substantial declines thereafter [22].

In the context of the acute yet differentiated developments regarding opioid availability and related harms, we examine possible over-time correlations between opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalizations across Canada for the period 2007–2016.

Methods

We used national data on community-based PO dispensing across Canada – i.e., here the 10 provinces – for the study period; the vast majority (e.g., ~ 80%) of opioid medications are dispensed through retail pharmacies [22]. Raw prescription opioid dispensing data, including both branded and generic medications, were obtained from IQVIA’s Compuscript prescription database, drawn from a representative, stratified, and continuously refreshed sample of ~ 6000 retail pharmacies towards estimating pan-Canadian dispensing total through patented geo-spatial projection methodology as previously used in related analyses [23,24,25]. Raw aggregate PO dispensing data included the numbers of units dispensed by product name, formulation and strength. These data were converted to annual values of Defined Daily Doses (DDD) per 1000 population per day (DDD/1000/day) as the measuring unit, based on the WHO’s Anatomical Chemical Classification as well as population statistics, by province and year for the study period (2007–2016 [26, 27];. DDDs are the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication for an average adult. While limited in accuracy, DDDs are a widely utilized measurement unit for comparative population-level analyses, and superior to crude indicators like prescription numbers [28]. We restricted our data to ‘strong’ opioids, based on the WHO’s ‘pain ladder’ i.e. excluding ‘weak’ opioids (e.g., codeine), as well as methadone due to differential dispensing modes as well as limited involvement in hospitalizations [22, 29].

Data on opioid-related hospitalizations in Canada came from published data from the Canadian Institutes of Health Information (CIHI)‘s Hospital Morbidity Database (HMDB). The HMDB is a national data-holding on administrative, clinical and demographic information on inpatient separations from acute care hospitals (but excluding EDs) from provincial data-sources across Canada [30, 31]. Opioid-related hospitalizations were identified based on admissions and length-of-time in hospital considered related to ‘significant opioid poisonings’, with discharge abstracts as the primary diagnosis, or comprised selected secondary diagnostic types based on ICD-10-CA codes (T40.0–4 and T40.6). Respective data, reported in population-based rates (per 100,000) were available by province for fiscal years (i.e., defined formally in Canada from 01 April to 31 March of the correspondingly following year) 2007/2008–2014/2015 and 2016/2017 (i.e., excluding data for 2015/16, as these were not available from the original data-source).

Possible correlations between annual provincial opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalization rates were assessed through the respective nine over-time data-pairs of indicators for each of the provinces, matching annual opioid-dispensing with corresponding hospitalization data for the corresponding annual time units (e.g., 2016 and 2016/17). Using the Pearson product moment correlation, ten province-specific correlation values and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated using the cor.test function of the R stats package (2018) [32].

Results

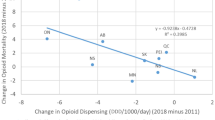

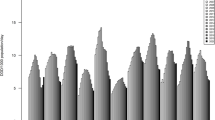

(see Table 1 for numeric data and Fig. 1 for corresponding visualizations).

For strong opioid dispensing, in 2007 (first observation year) the highest annual provincial rate was observed in Ontario (11.6 DDD/1000/day) and the lowest rate was in Quebec (4.9 DDD/1000/day) – constituting a > 2.3/1 ratio. Correspondingly, in 2016 (last observation year) Nova Scotia and New Brunswick featured the highest (11.4 DDD/1000/day) and Quebec had the lowest (6.5 DDD/1000/day) strong opioid dispensing rate – constituting a 1.7/1 ratio. All provinces featured higher strong opioid dispensing rates between the first and last observation year. While about half the provinces showed inverting trends in strong opioid dispensing – with annual levels initially rising and then decreasing – the other half featured consistent increases in strong opioid dispensing during the study period.

For opioid-related hospitalizations, in 2007/08 (first observation year) the highest annual rate was observed in Prince Edward Island (16.0/100,000) and the lowest rate was observed in Newfoundland and Labrador (7.1/100,000) – constituting a > 2.25/1 ratio. Correspondingly, in 2016/17 (last observation year) British Columbia featured the highest (25.0/100,000) and Quebec had the lowest (9.4/100,000) hospitalization rate – constituting a > 2.6/1 ratio. All provinces reported higher opioid-related hospitalization rates in 2016/17 compared to 2007/08. The majority of provinces featured varying (e.g., non-linear) trends in opioid-related hospitalization rates during the observation period.

The strongest correlation between opioid dispensing and hospitalization was observed for Quebec (r = 0.87, 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI): 0.49–0.97; p = 0.002); the weakest for Prince Edward Island (r = 0.20; 95%CI: − 0.53–0.76; n.s.). In a total of three provinces, significant correlations were observed: Quebec (see above); New Brunswick (r = 0.85; 95%CI: 0.43–0.97; p = 0.004) and Nova Scotia (r = 0.78; 95%CI: 0.25–0.95; p = 0.012); one province – Saskatchewan – (r = 0.073; 95%CI: − 0.07–0.91; p = 0.073) featured borderline significance (see Table 1 for data).

Discussion

Opioid-related morbidity substantially contributes to the extensive opioid-related disease and economic burden observed across North America [33,34,35]. Strong increases in opioid-related hospitalizations post-2000 have been observed in the US, as well as other countries with rising opioid availability [10, 12, 21, 36, 37].

We examined possible correlations between opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalization rates across Canada in contexts of most provinces featuring inversion patterns for opioid dispensing during the study period (2007–2016 [22];). These patterns reflect recent reductions in opioid availability following a variety of restrictive measures (e.g., intensified prescription monitoring, de-scheduling of select opioid formulations, restrictive opioid prescription guidelines) in a wider context of continuously rising opioid-related mortality and morbidity outcomes in Canada [3, 38, 39].

We identified significant correlations between opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalization rates for three (QC, NB, NS) of the ten provinces, with borderline significance in a fourth (SK). These results, partially, add to an extensive body of evidence identifying correlations between the volume of opioid availability and health harm outcomes on population levels [14, 15, 19, 40]. While these correlations were identified in select provinces, they were not identified in most others. These selective findings, however may not be coincidental when considering key ecological dynamics. Importantly, opioid-related hospitalizations data may comprise incidents related to both licit and illicit opioids, as the data used do not discriminate between opioids by legal status [8, 10, 41]. However, opioid availability data are limited to levels of medical opioid dispensing only. These circumstances, consequently, may involve a ‘contamination’ of hospitalization data through illicit opioid-related cases and a subsequent distortion or concealment of possible correlation effects.

In Canada, population-levels of illicit opioid use have been relatively limited, compared with high levels of (medical and non-medical) PO use estimated at > 20% and > 5%, respectively, in peak years around 2010 [42]. However, there have been strong increases in the availability of – highly potent and toxic – illicit synthetic opioid products (e.g., fentanyl, carfentanyl products) in Canada in more recent years, linked to substantial increases in fatal poisonings due to acutely elevated risk properties of these substances [4, 43, 44]. In this context, we note that significant (including borderline) correlations between opioid dispensing and hospitalizations were found specifically in four of the five Canadian provinces (PEI, NS, QC, NB, SK) reporting the lowest levels of contributions (< 25%) of (mostly illicit) fentanyl or fentanyl-analogue product involvement among opioid-related mortality in 2017 (i.e., ‘low contamination’ provinces); conversely, no correlations were observed in the provinces (MN, ON, AB, BC) with fentanyl products identified as a contributor to mortality in the majority (> 50%) of fatalities in 2017 (i.e., ‘high contamination’ provinces [7, 8, 41];). Similarly differential – but consistent with our results – patterns of illicit opioid involvement in opioid-related hospitalizations have been shown in analyses for select individual provinces [45]. These – rather consistent – differentiation patterns in our ecological study results allow to plausibly speculate that, in the absence of illicit opioid-related ‘contamination’ effects, the strength of province-based correlation signals between opioid dispensing and hospitalizations likely would have been more pronounced.

In this context, our findings of select Canada-based correlations between opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalizations provide additional evidence on associations between population-level opioid availability and key adverse health outcomes [34, 46,47,48]. This association – at least while supply for non-medical opioid use mostly involved prescription opioid products – had simple but essential implications: The higher the volume of opioids dispensed into the population, the higher the levels of consequential morbidity or mortality harms [15, 49, 50]. This insight provided a crucial knowledge base for guiding opioid policy and medical practice control (e.g., prescription guidance) in the distinct contexts of traditionally high opioid availability in North America, combined with evidence of only limited effectiveness of opioids for chronic pain therapy [51,52,53]. Beyond these current contexts, where illicitly produced opioids have increasingly replaced pharmaceutical opioids for non-medical use, these insights may be helpful for settings where opioid availability is still low and preventive restraints can facilitate appropriate balance between opioid availability and related adverse health outcomes [5, 38, 54, 55]. As a potentially relevant limitation for the present analyses, we note that the (general population-level) data examined did not include additional patient-level descriptors, or other data variables that could have been used to examine possibly confounding factors in the correlations assessed.

Conclusions

Our study identified correlations between over-time levels of prescription opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalizations in several provinces across Canada. These data further contribute to the evidence-base of population levels of prescription opioid availability and exposure, and opioid-related harms (e.g., morbidity, mortality). Correlations were mostly not observed in provincial jurisdictions where non-medical or illicitly produced opioids (e.g., fentanyls) have played an increasingly prevalent role in non-medical opioid use and harms in recent years, likely as an adverse consequence of recent restrictions on medical opioid availability (which may mask further correlations in regards to the specific data under study). Our study’s findings emphasize the need to reasonably limit the overall availability of and exposure to opioids in the population for general prevention.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are in the public realm and/or are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PO:

-

Prescription opioid

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- DDD:

-

Defined daily doses

References

Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, Kreiner P, Eadie JL, Clark TW, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559–74.

Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Cornish S, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The burden of premature opioid-related mortality. Addiction. 2014;109:1482–8.

Fischer B, Rehm J, Tyndall M. Effective Canadian policy to reduce harms from prescription opioids: learning from past failures. CMAJ. 2016;188(17–18):1240–4.

Belzak L, Halverson J. Evidence synthesis-The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promot Chron Dis Prev Can: Res Policy Pract. 2018;38(6):224.

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–45.

Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013–2017. Atlanta, USA: Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019.

Government of Canada. National Report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2019.

Gomes T, Khuu W, Martins D, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, et al. Contributions of prescribed and non-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: population based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ. 2018;362:k3207.

Armenian P, Vo KT, Barr-Walker J, Lynch KL. Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: a comprehensive review. Neuropharmacology. 2018;134:121–32.

Unick GJ, Rosenblum D, Mars S, Ciccarone D. Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin-and opioid-related overdoses, 1993-2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54496.

Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002–12. Health Aff. 2016;35(5):832–7.

Hsu DJ, McCarthy EP, Stevens JP, Mukamal KJ. Hospitalizations, costs and outcomes associated with heroin and prescription opioid overdoses in the United States 2001–12. Addiction. 2017;112(9):1558–64.

Spooner L, Fernandes K, Martins D, Juurlink D, Mamdani M, Paterson JM, et al. High-dose opioid prescribing and opioid-related hospitalization: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167479.

Fischer B, Jones W, Urbanoski K, Skinner R, Rehm J. Correlations between prescription opioid analgesic dispensing levels and related mortality and morbidity in Ontario, Canada, 2005-2011. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33(1):19–26.

Guy GP Jr, Zhand K, Bohm MK, Losby J, Lewis B, Young R, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697.

Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, Kerns RD, Eisenberg A, Ganoczy D, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among veterans health administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605–12.

Wisniewski AM, Purdy CH, Blondell RD. The epidemiologic association between opioid prescribing, non-medical use, and emergency department visits. J Addict Dis. 2008;27(1):1–11.

Modarai F, Mack K, Hicks P, Benoit S, Park S, Jones C, et al. Relationship of opioid prescription sales and overdoses, North Carolina. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:81–6.

Sauber-Schatz EK, Mack KA, Kiekman ST, Paulozzi L. Associations between pain clinic density and distributions of opioid pain relievers, drug-related deaths, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and neonatal abstinence syndrome in Florida. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):161–6.

Berecki-Gisolf J, Hassani-Mahmooei B, Clapperton A, McClure R. Prescription opioid dispensing and prescription opioid poisoning: population data from Victoria, Australia 2006 to 2013. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41(1):85–91.

Blanch B, Pearson SA, Haber PS. An overview of the patterns of prescription opioid use, costs and related harms in a ustralia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(5):1159–66.

Fischer B, Jones W, Vojtila L, Kurdyak P. Patterns, changes, and trends in prescription opioid dispensing in Canada, 2005-2016. Pain Physician. 2018;21(3):219–28.

CIHI. Pan-Canadian Trends in the Prescribing of Opioids and Benzodiazepines, 2012 to 2017. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI); 2018.

IQVIA. Canadian Pharmaceutical Trends: IQVIA; 2019. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/locations/canada/canadian-pharmaceutical-trends.

Schanzer D, Pogany L, Aho J, Tomas K, Gale-Rowe M, Kwong J, et al. Can we eliminate hepatitis C?: impact of availability of direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C on Canadian hospitalization rates, 2012–2016. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2018;44(7–8):150.

Svendsen K, Borchgrevink P, Fredheim O, Hamunen K, Mellbye A, Dale O. Choosing the unit of measurement counts: the use of oral morphine equivalents in studies of opioid consumption is a useful addition to defined daily doses. Palliat Med. 2011;25(7):725–32.

Sketris IS, Metge CJ, Ross JL, MacCara ME, Comeau DG, Kephart GC, et al. The use of the World Health Organisation anatomical therapeutic chemical/defined daily dose methodology in Canada. Drug Inf J. 2004;38(1):15–27.

Nielsen S, Gisev N, Bruno R, Hall W, Cohen M, Larance B, et al. Defined daily doses (DDD) do not accurately reflect opioid doses used in contemporary chronic pain treatment. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(5):587–91.

Raffa R, Pergolizzi J Jr. A modern analgesics pain ‘pyramid’. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39(1):4–6.

CIHI. Hospitalizations and Emergency Department Visits Due to Opioid Poisoning in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI); 2016. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Opioid%20Poisoning%20Report%20%20EN.pdf.

CIHI. Hospital Morbidity Database. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institutes for Health Information (CIHI); 2019. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/hospital-morbidity-database.

Core R. Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for statistical. Computing. 2018; Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

Florence C, Luo F, Xu L, Zhou C. The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse and dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care. 2016;54(10):901.

Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The burden of opioid-related mortality in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180217-e.

Belzak L, Halverson J. The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promot Chron Dis Prev Can: Res Policy Pract. 2018;38(6):224–33.

Unick G, Ciccarone D. US regional and demographic differences in prescription opioid and heroin-related overdose hospitalizations. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:112–9.

Chenaf C, Kaboré JL, Delorme J, Pereira B, Mulliez A, Zenut M, et al. Prescription opioid analgesic use in France: trends and impact on morbidity–mortality. Eur J Pain. 2019;23(1):124–34.

Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189(18):E659–E66.

Gomes T, Juurlink D, Yao Z, Camacho X, Paterson JM, Singh S, et al. Impact of legislation and a prescription monitoring program on the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions for monitored drugs in Ontario: a time series analysis. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(4):E256.

Dowell D, Zhang K, Noonan RK, Hockenberry JM. Mandatory provider review and pain clinic laws reduce the amounts of opioids prescribed and overdose death rates. Health Aff. 2016;35(10):1876–83.

Fischer B, Vojtila L, Rehm J. The ‘fentanyl epidemic’in Canada–some cautionary observations focusing on opioid-related mortality. Prev Med. 2018;107:109–13.

Murphy Y, Goldner E, Fischer B. Prescription opioid use, harms and interventions in Canada: a review update of new developments and findings since 2010. Pain Physician. 2015;18:E605–E14.

Baldwin N, Gray R, Goel A, Wood E, Buxton JA, Rieb LM. Fentanyl and heroin contained in seized illicit drugs and overdose-related deaths in British Columbia, Canada: an observational analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:322–7.

Fairbairn N, Coffin PO, Walley AY. Naloxone for heroin, prescription opioid, and illicitly made fentanyl overdoses: challenges and innovations responding to a dynamic epidemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:172–9.

Gomes T, Khuu W, Craiovan D, Martins D, Hunt J, Lee K, et al. Comparing the contribution of prescribed opioids to opioid-related hospitalizations across Canada: a multi-jurisdictional cross-sectional study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:86–90.

Degenhardt L, Charlson F, Mathers B, Hall WD, Flaxman AD, Johns N, et al. The global epidemiology and burden of opioid dependence: results from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1320–33.

Dowell D, Arias E, Kochanek K, Anderson R, Guy GP, Losby JL, et al. Contribution of opioid-involved poisoning to the change in life expectancy in the United States, 2000-2015. JAMA. 2017;318(11):1065–7.

King NB, Fraser V, Boikos C, Richardson R, Harper S. Determinants of increased opioid-related mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):e32–42.

Wright ER, Kooreman HE, Greene MS, Chambers RA, Banerjee A, Wilson J. The iatrogenic epidemic of prescription drug abuse: county-level determinants of opioid availability and abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:209–15.

Fischer B, Jones W, Rehm J. High correlations between levels of consumption and mortality related to strong prescription opioid analgesics in British Columbia and Ontario, 2005–2009. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(4):438–42.

Fischer B, Keates A, Bühringer G, Reimer J, Rehm J. Non-medical use of prescription opioids and prescription opioid-related harms: why so markedly higher in North America compared to the rest of the world? Addiction. 2014;109(2):177–81.

Els C, Jackson TD, Hagtvedt R, Kunyk D, Sonnenberg B, Lappi VG, et al. High-dose opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;10.

Busse JW, Schandelmaier S, Kamaleldin M, Hsu S, Riva JJ, Vandvik PO, et al. Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: a protocol for a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):66.

Fischer B, Pang M, Tyndall M. The opioid death crisis in Canada: crucial lessons for public health. Lancet Public Health. 2018;4(2):e81–e2.

Berterame S, Erthal J, Thomas J, Fellner S, Vosse B, Clare P, et al. Use of and barriers to access to opioid analgesics: a worldwide, regional, and national study. Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1644–56.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mrs. Lenka Vojtila’s assistance in assembling this manuscript.

Funding

The present work was partly supported by grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; #SAF-94814). Dr. Fischer acknowledges support from the endowed Hugh Green Foundation Chair in Addiction Research, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WJ co-conceptualized the study and conducted the data processing and statistical analyses. BF co-conceptualized the paper and led the writing. WJ, BF and PK reviewed and contributed to iterative drafts and provided intellectual contributions to the study. All authors approved the final manuscript submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No administrative permissions were required to access and use the data and records described in this manuscript. The prescription opioid dispensing data were generated based on retail dispensing information commercially obtained from IQVIA. The provider had no involvement in any stages of the study design, results, interpretation or decision to publish.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, W., Kurdyak, P. & Fischer, B. Examining correlations between opioid dispensing and opioid-related hospitalizations in Canada, 2007–2016. BMC Health Serv Res 20, 677 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05530-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05530-w