Abstract

Background

The weekend effect is the phenomenon of a patient’s day of admission affecting their risk for mortality. Our study reviews the situation at six secondary hospitals in the greater Helsinki area over a 14-year period by specialty, in order to examine the effect of centralization of services on the weekend effect.

Methods

Of the 28,591,840 patient visits from the years 2000–2013 in our hospital district, we extracted in-patients treated only in secondary hospitals who died during their hospital stay or within 30 days of discharge. We categorized patients based on the type of each admission, namely elective versus emergency, and according to the specialty of their clinical service provider and main diagnosis.

Results

A total of 456,676 in-patients (292,399 emergency in-patients) were included in the study, with 17,231 deaths in-hospital or within 30 days of discharge. A statistically significant weekend effect was observed for in-hospital and 30-day post-discharge mortality among emergency patients for 1 of 7 specialties. For elective patients, a statistically significant weekend effect was visible in in-hospital mortality for 4 of 8 specialties and in 30-day post-discharge mortality for 3 of 8 specialties. Surgery, internal medicine, and gynecology and obstetrics were most susceptible to this phenomenon.

Conclusions

A weekend effect was present for the majority of specialties for elective patients, indicating a need for guidelines for these admissions. More disease-specific research is necessary to find the diagnoses, which suffer most from the weekend effect and adjust staffing accordingly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The weekend effect is the phenomenon of a patient’s day of admission affecting their risk for mortality [1]. An end-of-week effect, i.e. a higher risk of mortality on Friday, Saturday, Sunday or Monday, has also been documented [2,3,4,5]. Much debate surrounds the suspected reasons behind the weekend effect: less elective patients at the weekend, [6] sicker patients at the weekend [7] and the unreliability of administrative data in regard to the variability in coding practices and the lack of certain information, e.g. co-morbidities and disease severity [8,9,10,11,12]. Many disease-specific studies have been carried out with conflicting results [13,14,15,16,17,18]. At the forefront of weekend effect research have been the United States, Great Britain and Australia with only a few disease-specific studies in the Nordic countries [17, 19,20,21,22]. Our study brings a specialty-specific point of view with one of the largest weekend effect databases in the Nordic countries. By examining specialty-specific mortality, we can distinguish which specialties would benefit most from changes in procedure and staff, allowing for prudent division of resources.

The Helsinki Hospital District numbers 23 hospitals with a catchment area of approximately 1.6 million inhabitants and its secondary hospitals cover approximately 400,000 inhabitants [23]. In this study, we examine the six secondary hospitals of the hospital district in an attempt to delve into the effects of the centralization of services on mortality. In our study focusing on the university hospital of the hospital district, we found a weekend effect in in-hospital and 30-day post-discharge mortality for almost all non-centralized specialties and half of centralized specialties amongst elective patients. About half of centralized specialties had a weekend effect in in-hospital mortality amongst emergency patients [24].

Methods

Of the administrative data of 28,591,840 patient visits from the years 2000–2013 in our hospital district, we extracted those in-patients treated in secondary hospitals who died during their hospital stay or within 30 days of discharge. We examined only those patients treated solely in secondary hospitals in order to investigate whether there was still a weekend effect after centralization of certain severe conditions to the university hospital. We eliminated those whose records were missing data, as well as day surgery patients and those admitted and discharged on the same day. Patients were then categorized according to the urgency of admission (elective versus emergency) and the specialty of their clinical service provider and main, most costly diagnosis, e.g. if a total hip replacement patient died of pneumonia, they were classified as a surgical patient. These specialties numbered eight: acute psychiatry, surgery, gynecology and obstetrics, internal medicine, pulmonology, neurology, pediatrics and otorhinolaryngology. The treatment of emergency otorhinolaryngology patients is centralized to the university hospital. Therefore, only elective patients were included in this data.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Administration of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District (Y1014KORV1). Ethics committee approval was not necessary due to national legislation which does not require ethics committee approval for a retrospective registry study without patient intervention, in accordance with the Medical Research Act of Finland [25, 26]. The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Outcomes

In-hospital mortality and 30-day post-discharge all-cause mortality were investigated in this study. We focused on examining the weekend effect and also identifying whether an end-of-week effect exists. We defined the weekend effect as higher mortality for patients admitted between midnight of Friday night and midnight of Sunday night and the end-of-week effect as higher mortality for patients admitted between midnight of Thursday night and midnight of Monday night. Public holidays occurring during the week are not included as weekends. These numbered seven to ten per year for the years of the study. This small number was unlikely to affect our findings radically and this same approach has been applied previously [11].

Covariates included in the study

Covariates examined in the study included age by age group, sex (male or female), admission day of the week (Sunday through Saturday), admission month (January through December), admission year (2000 through 2013), urgency of admission (elective or emergency), specialty of clinical service provider and risk category. Age was categorized by age group: < 20, 20–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69 and 70+ years old. Pediatric patients were grouped as follows: < 12 months, 12–23 months, 2 years to 4 years 11 months, 5 years to 9 years 11 months, 10 years to 14 years 11 months, 15 years to 19 years 11 months and 20+ years old. In Finland, the cut-off age for pediatric patients is usually 16 years. However, if treatment is near completion when the patient turns 16, the pediatric department routinely finishes it off. Hence, there are patients over the age of 16 in the pediatric data.

Statistical analysis

Due to a lack of information on co-morbidities and illness severity, we used five risk categories, into which we divided patients in this study according to the crude 30-day mortality rate by main discharge diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10) of the patients in this study [4]. A multivariable logistic regression model containing age, sex, risk category, weekday, year and month was applied to calculate the adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using R language (R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2019. https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Deaths

A total of 456,676 in-patients (292,399 emergency in-patients) were included in the study, with 17,231 deaths in-hospital or within 30 days of discharge (Table 1), for an overall crude mortality rate of 3.8%. Emergency patients comprised 14,973 deaths (86.9%) for a crude emergency mortality rate of 5.1% and a crude elective mortality rate of 1.4%. The majority of deaths occurred in the age group of 70+ years for all specialties, except acute psychiatry (50–59 years old) and pediatrics (0–1 years old).

Weekend admissions

Weekend admissions, i.e. admissions occurring on Saturday or Sunday, numbered 17.8% (n = 81,277), encompassing 15.8% of acute psychiatry patients, 15.1% of surgery patients, 18.5% of gynecology and obstetrics patients, 21.1% of internal medicine patients, 17.8% of pulmonology patients, 20.5% of neurology patients, 21.6% of pediatrics patients and 0.4% of otorhinolaryngology patients.

Emergency admissions

A statistically significant weekend effect was present amongst emergency patients in in-hospital mortality for internal medicine patients (p = 0.0000) (Table 2). In 30-day post-discharge mortality, a significant weekend effect was visible amongst internal medicine patients (p = 0.0001), with an end-of-the-week effect amongst surgery patients (p = 0.0364) (Table 3).

Elective admissions

Elective patients had a statistically significant weekend effect in in-hospital mortality for the specialties of surgery (p = 0.0011), gynecology and obstetrics (p = 0.0167), internal medicine (p = 0.0000) and pulmonology (p = 0.0074) (Table 2). A significantly higher risk for 30-day mortality was seen among elective surgery (p = 0.0022), gynecology and obstetrics (p = 0.0005) and internal medicine (p = 0.0010) patients at the weekend (Table 3).

Mortality by year

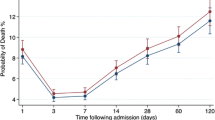

The overall adjusted odds ratio of mortality was at its lowest during 2004, with a rather steady rate starting from 2009 and continuing up until 2013 (Fig. 1). The overall adjusted odds of mortality across all specialties during the weekend (Saturday and Sunday) were below weekday mortality for the years 2002–2006 and 2010 (Fig. 2).

Mortality by sex

Of the specialties with patients of both genders, females had a statistically significant lower risk for in-hospital mortality for emergency acute psychiatry (adjusted OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.120–0.967), emergency surgery (0.80, 0.719–0.895), elective and emergency internal medicine (0.76, 0.624–0.914 and 0.75, 0.706–0.799) and for 30-day post-discharge mortality for emergency and elective acute psychiatry (0.24, 0.127–0.459 and 0.06, 0.008–0.505), emergency surgery (0.84, 0.764–0.916), emergency internal medicine (0.91, 0.856–0.974) and emergency pulmonology (0.73, 0.637–0.836).

Mortality by specialty

A decline in the annual crude mortality rate was seen for acute psychiatry (0.32% in 2000, 0.28% in 2013), surgery (3.5% in 2000, 2.3% in 2013), gynecology and obstetrics (0.2% in 2000, 0.04% in 2013) and internal medicine (8.4% in 2000, 6.8% in 2013), whereas an increase occurred for pulmonology (6.4% in 2000, 10.1% in 2013), neurology (1.1% in 2000, 5.1% in 2013), pediatrics (0.11% in 2000, 0.14% in 2013) and otorhinolaryngology (0% in 2000, 0.7% in 2013).

Discussion

We set out to investigate whether the weekend effect existed in the secondary hospitals of our hospital district. For almost all specialties and for both elective and emergency patients, a weekend effect was observed. However, these effects reached statistical significance in only about half of the specialties.

We observe a total of 1170 more deaths at the weekend because of the weekend effect (surgery n = 358, internal medicine n = 633, pediatrics n = 6, gynecology and obstetrics n = 19, neurology n = 61, acute psychiatry n = 4, pulmonology n = 89, otorhinolaryngology n = 0) when comparing the crude mortality rates of Saturday and Sunday admissions versus Wednesday admissions.

A significant weekend effect was observed in in-hospital and 30-day post-discharge mortality among emergency internal medicine patients. This coincides with previous findings of higher in-hospital mortality for both medical and surgical emergency diagnoses at the weekend [27, 28] and a higher risk for medical interventions [29]. In Finland, internal medicine in a secondary hospital is usually the specialty where medical students start their career. Medical school is a six-year program and fourth-year students are allowed to be on call in internal medicine emergency departments with attending physicians at home available by phone. This is one possible explanation why we only see a significant weekend effect among emergency patients in internal medicine.

For elective patients, a weekend or end-of-week effect was seen for the majority of specialties, which coincides with a current systematic review and meta-analysis [30]. Friday and weekend effects were seen in 30-day mortality among elective surgery patients [2]. The number of patients on Saturdays and Sundays was about one-third to one-half of that during the week, with this difference due in part to fewer elective patients. Fewer elective patients in turn increase the proportion of emergency to elective patients. Previously, some have hypothesized that fewer elective patients at the weekend is one reason for the weekend effect [6]. In our hospital district, sicker elective patients tend be admitted a day or two before surgery for monitoring, which most likely also contributes to the weekend effect seen in elective patients. Elective procedures on the weekend are often performed in order to shorten long wait times. These procedures are performed in addition to a regular 40-h work week. Staff fatigue may be one reason why those admitted at the weekend for an elective procedure had a higher risk of mortality.

Mortality by specialty and centralization of services

The centralization of healthcare services is a controversial topic. It has been at the forefront of political debate in Finland. Centralization increases the amount of a certain patient type treated, increasing experience through repetition. Conversely, patients may have to be transported a great distance to reach the centralized treatment center, thus falling prey to the golden hour phenomenon [31]. Patients living in the catchment area of Helsinki University Hospital may travel up to 200 km when off-hours specialized care is not available in a closer secondary hospital. Those in need of the advanced specialized treatment only Helsinki provides may travel up to 1200 km from northernmost Lapland.

There were no weekend effects for the specialties of acute psychiatry, otorhinolaryngology, neurology and pediatrics. The number of patients in these specialties was a fraction during the weekend of what it was during the week. The most difficult cases were also most likely transferred to the university hospital, thus leaving the simpler cases to be treated at the secondary hospitals and decreasing the probability of a weekend effect. Emergency otorhinolaryngology patients are centralized completely to the university hospital. Internal medicine was the only specialty with a weekend effect in both in-hospital and 30-day post-discharge mortality for both elective and emergency patients despite certain more serious conditions, for example ST-elevation myocardial infarction, being centralized to the university hospital. The specialties of surgery, internal medicine, and gynecology and obstetrics are the most sensitive to the weekend effect in both the university hospital and secondary hospitals. While the centralization of services to the university hospital is usually justified with the notion of decreased patient mortality, we found more statistically significant weekend effects in the non-centralized specialties at the university hospital than at secondary hospitals [24]. Numerous studies have shown that the centralization of low-volume surgical procedures, oncologic surgery and trauma patients lowers mortality [32,33,34]. However, this is not true in every diagnosis and patient group [35]. Therefore, we must delve into which diagnoses and patients benefit from centralization, which is the next step in our research.

Recently, weekend effect research was criticized for not scrutinizing care pathways before admission to hospital, with this being the reason for the weekend effect as opposed to a downturn in quality of care at the weekend [36]. Nevertheless, we observed a weekend effect even though our hospital admission pathway is the same on weeknights and at the weekend. In addition, the weekend effect was only visible in certain specialties and not detected in intensive care patients, the sickest patients of all [24].

Strengths of this study

As all residents of Finland are entitled to necessary health care and no off-hours private hospitals exist, our data is a very accurate depiction of the in-hospital treatment received in the municipalities of the greater Helsinki area. The catchment area of the hospital district remained the same during the whole study. The ancestry of the inhabitants of Finland is rather uniform [37], allowing us a relatively consistent patient set in respect to mortality risks.

Limitations of this study

Administrative data are noted for a variety of problems due to errors and missing data. We found that some specialties recorded co-morbidities well but others mainly recorded only the diagnoses pertaining directly to the hospital episode in question. In other words, in the case of a broken hip, codes for hip fracture and ensuing pneumonia are recorded but not for example diabetes, asthma and hypertension. Even when diagnosis codes are recorded, they do not tell of the severity of illness or whether the patient has reached their treatment target. A lack of co-morbidities in the data necessitated the use of the abovementioned risk categories to assess illness severity. While some have found a weekend effect regardless of illness severity [38], others showed the effect to be caused by sicker patients at the weekend [39]. Notwithstanding, the effect of disease severity is offset by the magnitude of this study population.

Patients’ socioeconomic variables were also not included. Hospitals in Finland do not record income, race, education level and other socioeconomic factors. This information also cannot be extrapolated from e.g. the patient’s address or zip code. When this study began in 2000, only 1.8% of the inhabitants of Finland were of foreign descent (0.5% of non-Caucasian descent), with only 3.8% of foreign descent (1.1% of non-Caucasian descent) in 2013 when this study finished, creating a rather uniform population [40]. The Finnish government has strived to avoid the development of underprivileged areas and public housing is interspersed all over the city. As education and health care is in practice free, there are not great differences between people or socioeconomic strata. Salaries and progressive income tax have also prevented the forming of the very rich or the very poor. As an example, the mean salary in Finland in 2018 was 3465 euros per month, the mode 2600 euros and median 3079 euros [41]. Due to these reasons, socioeconomic variables were not included.

Due to the lack of reliable time stamps, we were not able to differentiate between admissions occurring late Friday or early Monday morning versus those during office hours. This may be the cause of the end-of-week effect for some specialties as weekend staffing is from Friday 3:30 pm to Monday 8:00 am. The lack of co-morbidities and time stamps may allow for an omitted-variable bias but we attempted to compensate for this with the categorization of illness severity. Public holidays were not calculated as being part of the weekend if they did not fall on the weekend. We chose not to include public holidays as there were few during the week (between seven to ten per year) and this small amount was unlikely to affect our findings radically. The same approach was applied by Mohammed et al. with a similar number of bank holidays per year (eight) [11].

One historical effect was relevant in this study. Two secondary hospitals joined the university hospital in 2001. These two hospitals were included in this study for the year 2000 up until their joining Helsinki University Hospital in 2001. A clear spike is seen in mortality risk by year in 2001, which is possibly due to organizational changes and rearranging of services connected to the merger.

All six secondary hospitals included in the study belong to the hospital district of the same university hospital. They are all on the same level in regard to the severity of patient illness and care provided, as well as number of beds and staffing levels. Their only major difference is each hospital’s geographic catchment area. The hospital district’s catchment area has remained the same for the entire study period. All hospitals are, in practice, teaching hospitals as every doctor in Finland is required to guide and teach those less experienced. While the majority of medical students are trained at the university hospital, they do also receive training in these secondary hospitals. Residents also receive training during their specialization in these secondary hospitals. Due to these reasons, these variables were not included in our analyses. Adjusting for the particular secondary hospital might reduce possible confounding. However, in our opinion, it is improbable that adding the hospital as a random effect would materially change our results.

Conclusions

Findings of a higher risk for mortality for emergency and elective patients admitted at the weekend necessitate further research into the reasons and solutions for this problem. Solutions, including staffing with fewer residents and more specialists at the weekend, as well as a seven-day-a-week service, have been proposed. Nevertheless, restructuring of the resident versus specialist ratio would most likely require more doctors, thus ruling it infeasible in most countries without major changes in the healthcare system. Internal medicine, surgery, and gynecology and obstetrics were the specialties most sensitive to the weekend effect. We must examine the specific diseases, especially in these three specialties, that are sensitive to the weekend effect in order to focus funds and staffing changes accordingly. This is the next step for our group’s research. The centralization of services to the university hospital does not seem to eliminate the weekend effect, which undermines claims of centralization improving patient safety. Limitation of elective admissions during the weekend is crucial. Application of criteria for weekend elective admissions, e.g. reminiscent of day surgery criteria, is a possible approach to reducing the weekend effect through better patient selection.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- km:

-

Kilometer

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Honeyford K, Cecil E, Lo M, et al. The weekend effect: does hospital mortality differ by day of the week? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:3.

Aylin P, Alexandrescu R, Jen MH, et al. Day of week of procedure and 30 day mortality for elective surgery: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics. BMJ. 2013;346:f2424.

Zare MM, Itani KMF, Schifftner TL, et al. Mortality after nonemergent major surgery performed on Friday versus Monday through Wednesday. Ann Surg. 2007;246:866–74.

Ruiz M, Bottle A, Aylin PP. The global comparators project: international comparison of 30-day in-hospital mortality by day of the week. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:492–504.

Barnett MJ, Kaboli PJ, Sirio CA, et al. Day of the week of intensive care admission and patient outcomes: a multisite regional evaluation. Med Care. 2002;40:530–9.

Williams A, Powell AGMT, Spernaes I, et al. Mode of presentation rather than the ‘weekend effect’ is a major determinant of in-hospital mortality. Surg. 2019;17:15–8.

Freemantle N, Ray D, McNulty D, et al. Increased mortality associated with weekend hospital admission: a case for expanded seven day services? BMJ. 2015;351:h4596.

Deeny SR, Steventon A. Making sense of the shadows: priorities for creating a learning healthcare system based on routinely collected data. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:505–15.

Li L, Rothwell PM, Oxford Vascular Study. Biases in detection of apparent “weekend effect” on outcome with administrative coding data: population based study of stroke. BMJ. 2016;353:i2648.

Wennberg JE, Staiger DO, Sharp SM, et al. Observational intensity bias associated with illness adjustment: cross sectional analysis of insurance claims. BMJ. 2013;346:f549–9.

Mohammed MA, Sidhu KS, Rudge G, et al. Weekend admission to hospital has a higher risk of death in the elective setting than in the emergency setting: a retrospective database study of national health service hospitals in England. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:87.

Concha OP, Gallego B, Hillman K, et al. Do variations in hospital mortality patterns after weekend admission reflect reduced quality of care or different patient cohorts? A population-based study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:215–22.

Saposnik G, Baibergenova A, Bayer N, et al. Weekends: a dangerous time for having a stroke? Stroke. 2007;38:1211–5.

Inoue T, Fushimi K. Weekend versus Weekday Admission and In-Hospital Mortality from Ischemic Stroke in Japan. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:2787–92.

Isogai T, Yasunaga H, Matsui H, et al. Effect of weekend admission for acute myocardial infarction on in-hospital mortality: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2015;179:315–20.

Sorita A, Lennon RJ, Haydour Q, et al. Off-hour admission and outcomes for patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Am Heart J. 2015;169:62–8.

Kristiansen NS, Kristensen PK, Norgard BM, et al. Off-hours admission and quality of hip fracture care: a nationwide cohort study of performance measures and 30-day mortality. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28:324–31.

Nandra R, Pullan J, Bishop J, et al. Comparing mortality risk of patients with acute hip fractures admitted to a major trauma centre on a weekday or weekend. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1233.

Hansen KW, Hvelplund A, Abildstrøm SZ, et al. Prognosis and treatment in patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction on weekends and weekdays from 1997 to 2009. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1167–73.

Group HSTR. Does time of day or physician experience affect outcome of acute ischemic stroke patients treated with thrombolysis? A study from Finland. Int J Stroke. 2012;7:511–6.

Murray IA, Dalton HR, Stanley AJ, et al. International prospective observational study of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: does weekend admission affect outcome? United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:1082–9.

Nilsen SM, Toch-Marquardt M, Anthun KS, et al. Time of admission and mortality after hip fracture: a detailed look at the weekend effect in a nationwide study of 55,211 hip fracture patients in Norway. Acta Orthop. 2018;89:610–4.

Population by Municipality 2000–2019, https://www.kuntaliitto.fi/tilastot-ja-julkaisut/kaupunkien-ja-kuntien-lukumaarat (2019, accessed 17 July 2019).

Tolvi M, Mattila K, Haukka J, et al. Analysis of weekend effect on mortality by medical specialty in Helsinki University hospital over a 14-year period. Submitt Publ.

Medical Research Act, https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990488_20100794.pdf (1999, accessed 21 March 2020).

The Government’s Proposal 65/2010 vp to Parliament on the Medical Research Act (Hallituksen esitys 65/2010 vp Eduskunnalle lääketieteellisestä tutkimuksesta annetun lain, potilaan asemasta ja oikeuksista annetun lain 13 §:n sekä sosiaalihuollon asiakkaan asemasta ja oikeuksista annetun lain 18 §: muuttamisesta, https://www.finlex.fi/fi/esitykset/he/2010/20100065.pdf (2010, accessed 21 March 2020).

Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Read TE, et al. Mortality rate after nonelective hospital admission. Arch Surg. 2011;146:545–51.

Zhou Y, Li W, Herath C, et al. Off-hour admission and mortality risk for 28 specific diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 251 cohorts. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003102.

Huang C-C, Huang Y-T, Hsu N-C, et al. Effect of weekend admissions on the treatment process and outcomes of internal medicine patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2643.

Chen Y-F, Armoiry X, Higenbottam C, et al. Magnitude and modifiers of the weekend effect in hospital admissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025764.

Rogers FB, Rittenhouse KJ, Gross BW. The golden hour in trauma: dogma or medical folklore? Injury. 2015;46:525–7.

Ely S, Alabaster A, Ashiku SK, et al. Regionalization of thoracic surgery improves short-term cancer esophagectomy outcomes. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:1867–78.

Ahola R, Siiki A, Vasama K, et al. Effect of centralization on long-term survival after resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2017;104:1532–8.

Muguruma T, Toida C, Gakumazawa M, et al. Effects of establishing a trauma center on the mortality rate among injured pediatric patients in Japan. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217140.

Williams JH, Jarosek S, Carroll N, et al. Health system affiliation and 30-day readmission after heart attack in black men. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:S22–30.

Rudge G. The rise and fall of the weekend effect. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2019;24:217–8.

Structure of the Finnish Population. 2019, https://www.tilastokeskus.fi/tup/suoluk/suoluk_vaesto.html.

Duvald I, Moellekaer A, Boysen MA, et al. Linking the severity of illness and the weekend effect: a cohort study examining emergency department visits. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26:72.

Sun J, Girling AJ, Aldridge C, et al. Sicker patients account for the weekend mortality effect among adult emergency admissions to a large hospital trust. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:223–30.

Tilastokeskus (Statistics Finland). Population Structure by Citizenship, http://vertinet2.stat.fi/verti/graph/viewpage.aspx?&ifile=quicktables/maahanmuuttajat/kansa_1&lang=3&rind=1&x=880&y=660&gskey=2&mover=no (2020, accessed 8 March 2020).

Tilastokeskus (Statistics Finland). Palkat ja työvoimakustannukset, https://www.tilastokeskus.fi/tup/suoluk/suoluk_palkat.html (2019, accessed 8 March 2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Seppo Ranta and Tuuli Pajunen for their expert advice in the planning of this study and its database.

Funding

This work was supported by Finnish Governmental Research Grant, The Finnish Medical Association and The Otologic Research Fund of Finland. Grants from these funders provided for MT to take research leave from clinical work. The funders did not in any way contribute to the design of the study or data collection, analysis or interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT, LL, KM and LMA devised the study design. JH performed the statistical analysis of the data. MT, LL and KM prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Administration of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District (Y1014KORV1). Ethics committee approval was not necessary due to national legislation which does not require ethics committee approval for a retrospective registry study without patient intervention, in accordance with the Medical Research Act of Finland.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tolvi, M., Mattila, K., Haukka, J. et al. Weekend effect on mortality by medical specialty in six secondary hospitals in the Helsinki metropolitan area over a 14-year period. BMC Health Serv Res 20, 323 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05142-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05142-4