Abstract

Background

It is increasingly recognized that improving the quality of maternal health care delivery is of utmost importance in many countries. In Laos, the quality of antenatal care (ANC) service remains inadequate, but it has never been assessed thoroughly. This study aims to determine the ANC quality at the urban and rural public health facilities in Laos and provides suggestions to improve health education and counseling in addition to other routine care in public ANC services.

Methods

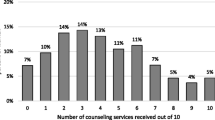

This health-facility based, cross-sectional observation study included both health providers (n = 77) and pregnant women (n = 421) from purposively selected health facilities (n = 16). Information on the mothers’ current pregnancies, previous visits and their last children was collected. The time spent for each ANC session as well as ANC services provided were recorded. Descriptive and inferential statistics were applied to analyze the data.

Results

Overall performance of ANC services by health care providers was poor in both urban and rural areas. Insufficient provision of information on danger signs during pregnancy, nutrition, breast feeding and iron supplements was revealed. Generally the communication skills, behavior and attitude of health providers were very poor. Less than a quarter of pregnant women were treated with kindness and respect. Only 4% of the observed ANC session took privacy into consideration. Less than 10% of available information materials were used during each ANC session. None of the health providers in both rural and urban areas performed specific counseling. Overall mean (SD) time-spent for each ANC session was 16.21 (4.28) minutes. A positive correlation was identified between the length of working experience of health providers and their physical performance scores (adjusted R square = 0.017).

Conclusions

The overall performance of ANC services by health care providers was inadequate in both urban and rural areas. Insufficient provision of health education and poor communication skills of health care providers were revealed. Existing IEC materials were scarcely used. Taking action to improve the quality of ANC services by training and providing specific guidelines, creating dedicated rooms, and providing sufficient and effective materials for counseling are all greatly needed in public health facilities in Laos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Effective pre-, intra-, and post-natal care interventions play an important role in reducing maternal and child mortality and morbidity [1,2,3,4,5]. Antenatal care (ANC) is the care that a woman receives throughout her pregnancy and for some weeks during the post-partum period in addition to identification of problems occurring during pregnancy [1, 6], ANC provides an excellent opportunity to establish a birth plan and to promote a healthy lifestyle that improves health outcomes for the woman, her unborn child and possibly her family [7, 8]. Besides medical history-taking and physical examination, treatment and referral to a hospital, health education and counseling play an important role in ANC [9,10,11].

Good health education and counseling in ANC means that a pregnant woman should be fully informed about the progress of her pregnancy and that she is provided with evidence-based information and support to make informed decisions, in a manner suitable to her culture and life experience [10, 12]. Pregnant women and their family members should have the opportunity to be informed about care, treatment, and possibility of unexpected matters, in partnership with their health care providers [12].

A previous study demonstrated that more women changed their behavior for reducing adverse pregnancy outcomes after having received nutrition counseling [13, 14]. In other studies, the positive effect of health education and counseling was significantly associated with improvement of maternal behaviors and health outcomes [13, 15, 16]. It has been shown that individual counseling with weekly reinforcement can bring about improvement in nutritional status during pregnancy [17].

However, in actual practice, the quality of ANC services is often poor in low-and middle-income countries and the information provided often does not match the social and cultural context of women to promote their healthy behavior at home [12, 18]. Improving this approach will strengthen the link between women and their family members and the health services during and after childbirth and may also help to promote delivery at health facilities, breastfeeding and a healthy lifestyle [12, 18].

Laos, where this study was done, is no exception. Although access to ANC has improved over the past decade [19, 20], the quality of ANC service remains inadequate [21], and there are indications that especially counseling is usually not practiced well at public health facilities [22]. The poor health education and counseling provided by health care workers has not yet been explicitly addressed in health interventions, just as poor public awareness and empowering women have not.

Very little is known about the current practice of Lao health care workers providing ANC services at the public health facilities. A recent study provided evidence of the perspectives and experiences of both supply and demand sides as to this issue, based on in-depth interviews (submitted for publication). However, the actual providers’ practice on health education and counseling was not described in that report. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted an observational study on the current practice of ANC health education and counseling to pregnant women by health providers at public health facilities in both urban and rural areas. The study aims to assess the ANC quality at the public health facilities in Laos; the results provide suggestions to improve health education and counseling in addition to other routine care in public ANC services.

Methods

Study design and sites

We conducted a health facility based, cross-sectional observational study, covering 16 public health facilities that routinely provide ANC services. The four central hospitals (Mahosot, Setthathirath, Mother and Newborn, and Friendship) in Vientiane Capital are located in urban settings, while the two provincial hospitals (Salavan and Attapeu), four district hospitals (two in Salavan and two in Attapeu), and eight health centers (four in Salavan and four in Attapeu) are located in rural areas.

Classification of urban and rural areas is based on the distribution of the population [23]. The population density of Salavan and Attapeu provinces is less than 50 people per Km2 while that of Vientiane Capital is 209 per Km2 [24].

These health facilities were purposively selected for the study for the following reasons: (1) these health facilities represent both urban and rural areas, as well as different levels (central, provincial, district hospitals and local health centres); (2) these facilities were also used in a previous study using in-depth interviews to explore the perspectives and experiences of supply and demand sides on the quality of ANC provision by health care providers, aimed at improving quality of ANC provision (submitted for publication), so that conducting observation to assess the quality of ANC in the same areas helps to relate the information from the real practice of health care providers to compare with the previous results. Perhaps most importantly, we plan to use the information from both interviews and the current observational study as a baseline for future interventions in these areas.

The sample size for the study was calculated using http://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html and based on the available Lao data from 2016, that the number of households with a pregnant woman is 192,000 and the Lao Social Indicator Survey in 2017 showing that 87.4% of Lao pregnant women attended at least one ANC visit [20]. We should recruit at least 420 pregnant women and we recruited 421 (81 were from urban and 340 from rural areas as shown in Table 1). Distribution of number of participants to be observed for each ANC session in the urban and rural areas was based on the feasible number of observations per day and all health providers who provided ANC service were included.

Study participants

This study involved both health providers and pregnant women who attended ANC. Health providers including doctors, nurses, and midwives currently practicing at the ANC services with at least 1 year of working experience at that health facility were invited to participate. Pregnant women and family members who visited the study site ANCs during the observation sessions were also invited.

Research instruments

A checklist for ANC session observation was developed from “The WHO recommendation on ANC services for positive pregnancy experience” and a counseling handbook of WHO [10, 11], both of which are used to train Lao ANC providers. The checklist had five sections: (1) medical history taking; (2) physical examination; (3) providing health promotion during pregnancy, for childbirth and postpartum care; (4) health education material to be used during ANC provision; and (5) effective communication skills, behavior and attitude of health providers. The checklist was firstly developed in English; thereafter back and forth translation was made between English and Lao languages to ensure accuracy. The checklist tool in Lao language was pilot tested at different health facilities in the study areas and edited where needed. The checklist can be provided as requested.

Data collection

Data collection was carried out from July to August 2017. Two Lao nurses and two midwives with two to 4 years’ working experience in ANC from Vientiane were recruited and trained for data collection. Authors SP and MM trained them for 3 days, using role-play to demonstrate how to observe the performance of the health providers and fill in the observation checklist. During the training, the four data collectors practiced data collection at the ANC of health facilities not included in the study. They were closely monitored and supervised in the field by the two trainers.

Prior to data collection, the health providers and pregnant women were fully informed about the study objectives and observation procedure. Information on the mothers’ current pregnancies was obtained through observation and their ANC card. Information on previous visits and their last children was collected from ANC cards. During the study, almost all of the women (98%) brought their ANC cards when visiting the ANC. Women who did not bring their cards were excluded from the study. The time spent for each ANC session, excluding waiting time and registration, was recorded.

Each observer noted the health provider’s performances during observation and then recorded the relevant information on the checklist, in addition to the information from the woman’s ANC cards and the time spent (in minutes) on the ANC consultation. At the end of each day, characteristics of the health providers (age, sex, profession and working experience) were collected in a brief interview. The observers sat approximately two meters away from the health providers and pregnant women to observe the consultation session.

Data analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel (2011) for Mac. Data were then transferred to ‘IBM SPSS 25’ for analysis. Descriptive statistics, such as percentage, mean (SD) and median (range), were applied to describe the characteristics of health providers and pregnant women’s personal information. The performance scores of health providers on history taking, physical examination, health promotion during pregnancy, for childbirth and postpartum care, including communication skills, were calculated as well as the time spent for each ANC session. When any performance item was conducted by the health provider regardless of whether it was right or wrong, a score of 1 was given; if the item was not done the score was 0.

Comparison of proportion between two groups was made using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Mann Whitney-U or Student’s t tests were applied to compare medians or means between groups. The relationship between ANC performance scores of health providers and their working experience and age was explored using Pearson or Spearman correlation tests as appropriate, and multiple linear regression was applied to check for confounding by time-spent, age and working experience of health care providers.

Results

A total of 77 ANC providers (20 from urban and 57 from rural areas) were enrolled in the study. During the study period, 421 observation sessions with 421 pregnant women (81 in urban and 340 in rural areas) were conducted.

The characteristics of health providers are shown in Table 2. Their overall mean age was 35 years, 98.7% were female and about 60% were nurses. Their median working experience was 11 years, ranging from 1 to 33 years, and was significantly higher in urban [17 (1–33)] than in rural [9 (1–29)] areas (P = 0.042).

The characteristics of pregnant women who visited ANC are presented in Table 3. These women were relatively young, with mean age of 25 years, which was not significantly different in urban and rural areas. At the time of observation, 55.6% of the pregnant women were visiting ANC in their third trimester; the overall median and range of gestational age was similar in urban and rural areas. Approximately one third of the women came for ANC alone, although this was significantly more common in urban than in rural areas (P = 0.003).

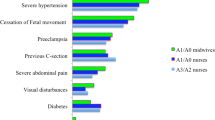

Overall, the medical history taking and physical examination performance by the health providers were relatively poor, as shown in Table 4. Six questions were related to ‘medical history taken’. Out of a maximum possible score of 6, the median was 3, and it was significantly higher in rural than in urban areas (P = 0.007). Half of the providers asked about the mothers’ last menstruation, prior pregnancies, current pregnancy problems and any medicines taken by the mothers during their pregnancies, while only one third of them asked about mother’s previous pregnancy problems. The percentage of the providers who asked about mothers’ age, last menstruation, and prior pregnancies was significantly lower in urban as compared to rural areas (P < 0.001, P = 0.01, and P = 0.002, respectively). The median score out of 6 was significantly lower in urban than in rural areas (P = 0.007). Observation of performance of the six items of physical examination resulted in higher scores, which were significantly lower in rural than in urban areas (P = 0.002) (Table 3). However, looking at the average scores, it appears that only examination of the abdomen was done in more than 70% of the cases, while in only 41.6% of the consultations did the health providers listen to the fetal heartbeat.

The providers’ performance on other procedures was also poor. For example, washing hands before examination was only 6.7% and privacy during examination was ensured in only 4.0% of cases. The grand total score on the physical examination process was significantly higher in urban than in rural areas (P < 0.001).

Although the health providers from urban areas provided more health promotion messages to the mothers as compared to those in the rural areas, their overall performance for this service remained unsatisfactory (Table 5). For example, each of eight items separately was performed in less than 50% of the observations. The overall median score out of a possible 8 on health promotion during pregnancy was only 2 and was significantly lower in rural than urban areas (P < 0.001).

Health promotion on childbirth and postpartum care to mothers by the providers both in urban and rural areas was also very poor, as illustrated by the data in Table 4. For example, just 47.3% of the providers gave advice on a safe place for childbirth, and only 15% advised mothers to bring their children for vaccination. None of them provided counseling on child vaccination, breastfeeding and nutrition. The overall median score for health promotion on childbirth and the postpartum period out of a possible 12 was only 2; although both were very low, the score was significantly higher in urban than in rural areas (P < 0.001).

The availability of health education materials for each ANC session observed and their use during health education by health providers at the public health facilities was highly inadequate as shown in Table 6. Health education materials were used to provide health information in fewer than 10% of the sessions, although more than 50% of required health education materials were available at each health facility at the time. The very low frequency of using materials to explain about diet during pregnancy (9.7%), after childbirth (2.6%), and for child vaccination (3.6%) was not significantly different between urban and rural areas.

The results of assessing the performance of health providers’ communication with the mothers are presented in Table 7. Generally, the communication between health providers and their clients had a lot of weaknesses. Except for sitting at the same level and using simple language with the mothers, other communication items expressed or performed by the health providers were inadequate. For example, the items helping brainstorming, agreeing on an appointment for the next visit, asking if there are more questions, and encouraging to ask questions were almost never performed. The overall median score out of 24 on communication was only 6; there was no significant difference between urban and rural areas.

The overall mean time spent for ANC per visitor was 16.21 min (SD 4.28), and it was significantly longer in rural [20.65 (4.92)] than in urban [15.15 (3.33)] areas (P < 0.001). Paradoxically, significant negative correlations were found between time spent and physical examination scores [r = − 1.117*, P = 0.016] and time spent and health promotion [r = − 1.200*, p = 0.013]. Time spent for medical history scores and counseling scores were not correlated. Total performance scores were also not significantly correlated, though a negative trend was observed.

Further analysis using Pearson or Spearman correlation tests revealed correlations between health providers’ working experience and age and their performance scores. There was a significantly positive correlation between working experience and age of health providers and their physical examination performance scores [r = 0.301** (n = 77), P = 0.008 and r = 0.285** (n = 77), P = 0.024, respectively]. In a multiple linear regression analysis, working experience of health providers was independently correlated with their physical performance scores (adjusted R square = 0.017).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Laos to assess the working performance of the ANC health workers, with special emphasis on the provision of information and counseling to their clients by using structured observation at public health facilities. The findings demonstrate that the overall performance of ANC providers was very poor in both urban and rural areas.

Thus although women are accessing ANC, they are not benefiting optimally from ANC services. They are not sufficiently protected through direct screening; do not get enough information on safe pregnancy or on how to nurture the child in the first 1000 days. Medical history taking and physical examination in ANC service are crucial for initial assessment to detect danger signs that may need treatment or referral to a higher level health facility [6, 12]. We found that performance on history taking remained poor, while physical examination was adequate but needs improvement. It is especially worrisome that in fewer than half of the cases observed did providers listen to the fetal heartbeat. Similar findings were reported from Tanzania [25]. If ANC is not carefully conducted, preventable health issues can be missed, such as hypertension and edema (pre-eclampsia and eclampsia), of caus important maternal death during pregnancy [26].

We found that medical history taking by health providers was better in rural than in urban areas, but the opposite was true for physical examination and other procedures. There may be different reasons for this finding. For example, time constraints can be an important factor, contributing to inadequate performance by health providers where facilities are overcrowded (submitted for publication). In this study, however, there was a negative correlation between time spent per consultation and performance in physical examination and health promotion. The approximate number of clients per day was 40 in urban and 10 in rural areas. This finding therefore requires further research. On the other hand, ANC services in urban areas often focus on high-risk screening in addition to routine ANC, while the rural areas provide basic services.

The results of our study clearly demonstrate that the provision of health promotion messages by health workers to clients in both urban and rural areas remains inadequate. During ANC visits, all pregnant women should have the opportunity to be fully informed about their pregnancy and given evidence-based information to help them make decisions [2, 6, 12]. Unfortunately, the pregnant women in the locations we studied received very little information; less than one quarter of them was given health promotion messages. The situation was similar situation in rural Burkina Faso, Uganda and Tanzania, where less than 20% of health workers provided health education to pregnant women and only 2 to 7% of women received information on danger signs of pregnancies [27].

Strengthening the relationship between pregnant women, their family members and health providers would also help to promote childbirth at health facilities, as well as breastfeeding and a healthy lifestyle [12, 18]. Unfortunately, family members who accompanied pregnant women to visit ANC in our study did not have the opportunity to be informed about care, treatment, and or possibility of unexpected problems, because they were not invited to attend during ANC sessions together with pregnant women (submitted for publication).

Although effective counseling can help to improve women’s behavior and health outcomes [15, 16], none of the health providers in this study performed counseling on nutrition, child vaccination, and breastfeeding. This was probably due to lack of training, guidelines, and a specific private room for counseling in the public health facilities in Laos [28, 29].

Information materials seemed to be a neglected component for ANC provision at public health facilities in Laos. Our study demonstrated that ANC health care providers rarely apply IEC materials for their health promotion activities even when they were available – this may be due to insufficient materials and/or to lack of good training. This is supported by the findings from another recent study in which health workers reported that they lacked materials and guidelines to use at their health facilities, and a lack of training on how to use existing materials effectively (submitted for publication).

The health care providers’ communication skills influence women’s satisfaction with maternal health care services [30]. Improvement of those communication skills, for example by training, should enhance their information provision and increase women’s involvement in their own health care [31]. The results of this study also suggest that communication between health care providers and their clients is still very weak. Health care providers need to show more kindness and respect, and need more privacy for communication with their clients. A study in Ethiopia on clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication also demonstrated that pregnant women were particularly dissatisfied about information provision and the time limitations of consultations [32].

Limitations of the study

The purposive sampling method used for the study meant that the findings may not be widely generalizable. Not all behaviors of the health care providers are open to observation and the observers may have personal bias. There was no video recording, so important information during the observation might have been missed. The observation itself might influence actual practices between health care providers and clients. Comparative analysis between over and covert observation methods is recommended for further observational study.

Conclusion

The overall performance of ANC services by health care providers at the public health facilities in Lao PDR was observed to be inadequate in both urban and rural areas. Insufficient provision of health education and poor communication skills of health care providers were revealed. Existing IEC materials were scarcely used for health education by health care providers both in urban and rural areas even when they were available. Taking action to improve the quality of ANC services by training and providing specific guidelines, creating separate rooms, and providing sufficient and effective materials to be used for counseling is urgently required at the public health facilities in Laos.

Availability of data and materials

Authors would like to confirm that the raw data of the manuscript can be provided with an appropriate request.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Ante-natal Care

- IEC:

-

Information Education and Communication

- Lao PDR:

-

Lao People’s Democratic Republic

- LMIC:

-

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- MCNV:

-

Medical Council Netherland and Vietnam

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kuhnt J, Vollmer S. Antenatal care services and its implications for vital and health outcomes of children: evidence from 193 surveys in 69 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e017122.

K. Oyerinde. ‘Community medicine & health education can antenatal care result in significant maternal mortality reduction in developing countries ?’. 3;2:2–3, 2013.

Bergsj P. What is the evidence for the role of antenatal care strategies in the reduction of maternal mortality and morbidity? 2001.

Y. M. RN, ‘Relationship of antenatal care with the prevention of maternal mortality among pregnant women in Bauchi state Nigeria’, IOSR. J Res Method Educ 5;4:35–38, 2015.

Oyerinde K. Can antenatal care result in significant maternal mortality reduction in developing countries? Community Med Heal Educ. 2013;3(2):2–3.

MOHS, National Guidelines for antenatal care. 2018.

Halle-Ekane GE, et al. Quality of antenatal care and outcome of pregnancy in a semi-urban area in Fako division, Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Women Heal Open J. 2015;1(2):31–9.

Piego JH. Focused antenatal care: planning and providing care during pregnancy. Matern Neonatal Heal. 2004.

Al-rusaiess AA. Health education during antenatal care : the need for more. 2015:7;239–42.

WHO, Counselling for maternal and newborn health care. 2014.

WHO, ‘Recommendation on Antenatal care for positive pregnancy experience’, 2016.

WHO, ‘Provision of effective antenatal care integrated management of pregnancy and childbirth (IMPAC) standards’, 2006.

Girard AW, Olude O. Nutrition education and counselling provided during pregnancy: effects on maternal, neonatal and child health outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(1):191–204.

Finlayson K. Global access to antenatal care: a qualitative perspective. Pract Midwife. 2015;18:2.

Villadsen SF, et al. Antenatal care strengthening in Jimma, Ethiopia : a mixed-method needs research article antenatal care strengthening in Jimma, Ethiopia: A Mixed-Method Needs Assessment; 2014. p. 10.

Sharifirad GR, Tol A, Mohebi S, Matlabi M, Shahnazi H. The effectiveness of nutrition education program based on health belief model compared with traditional training, vol. 2; 2013. p. 1–5.

Gross K, Schellenberg JA, Kessy F, Pfeiffer C, Obrist B. Antenatal care in practice: an exploratory study in antenatal care clinics in the Kilombero Valley, South-Eastern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):36.

WHO, ‘The World Health Organization Reported in 2005. Make every mother and child count’, 2005.

Tanner J, Hayashi R, Li Y. Improving coverage and utilization of maternal and child health Services in Lao PDR; 2015.

LSIS, ‘Lao social Indicator survey II (LSISII) in 2017’, 2018.

Manithip C, Edin K, Sihavong A, Wahlstr R, Wessel H. Poor quality of antenatal care services — is lack of competence and support the reason ? An observational and interview study in rural areas of Lao PDR. Midwifery. 2013;29:195–202.

MOH, ‘Health sector reform strategy and framework till 2025 the lao people ’ s democratic republic’, 2016.

David R, Jill H. Urban-rural classification : Identifying a system suitable for transit; 2008.

Lao Statistics Bureau. Result of population and housing census 2015. Lao Stat Bur. 2016;2015:282.

Miltenburg AS, Van Der Eem L, Nyanza EC, Van Pelt S. Antenatal care and opportunities for quality improvement of service provision in resource limited settings : a mixed methods study; 2017. p. 1–15.

Alkema L, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the un maternal mortality estimation inter-agency group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–74.

K. Et al Gross. Antenatal care in practice : an exploratory study in antenatal care clinics in the Kilombero Valley; 2011. p. 1–11.

Manithip C, Sihavong A, Edin K, Wahlstrom R, Wessel H. Factors associated with antenatal care utilization among rural women in Lao People ’s democratic republic; 2011. p. 1356–62.

Sychareun V, et al. Provider perspectives on constraints in providing maternal, neonatal and child health services in the Lao People’s democratic republic: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):243.

NARC, ‘MNCH-pmtct communication strategy: Johns hopkins bloomberg school of public health, center programs, national AIDS resource center’. 2011.

R. E. Rowe et al., ‘Improving communication between health professionals and women in maternity care : a structured review’, 2002.

Asifere WN, Tessema M, Tebeje B. Clients ’ satisfaction with health care providers ’ communication and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Jimma town public health facilities , Jimma zone , southwest. Int J Pregnancy Child Birth. 2018;4(5):223–30.

Paul Conrad, Gerhrd Schmid, Justin Tientrebeogo, Arinaitwe Moses, Silvia Kirenga, Florian Neuhann, Olaf Müller, Malabika Sarker. Compliance with focused antenatal care services: do health workers in rural Burkina Faso, Uganda and Tanzania perform all ANC procedures?. Tropical Medicine & International Health: no-no. 2011.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to give special thanks Dr. Phouthone Vangkonevilay, Dr. Chanthanom Manithip, Dr. Sengchanh Kounnavong, Dr. Vanphanom Sychareune, Dr. Vongsinh Phothisansack, Dr. Kongmany Chalearnvong, Dr. Visanou Hansana, Dr. Alongkone Phengsavanh, Mr. Ian Bromage, Mr. Stephen Himley, Mrs. Suzanna Lipscombe, Dr. Leonie Venroij and my family members for their kind support and encouragement. In addition, we would like to thank our research assistants from the University of Health Sciences and health facilities, Laos who contributed their best effort to collect data for this study. We also would like to express our sincere thanks to Salavan and Attapeu provincial and district health departments for their excellent collaboration in the fieldwork. Finally we would like to give our heartfelt thanks to all participants at the central, district, and community levels for sharing their valuable time and information to participate in this study.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was part of a research project on the situation analysis of maternal and child health care in Lao PDR, which received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Ministry of Health, Lao PDR. We obtained written informed consent from all pregnant women and health care providers before beginning with observation.

Funding

The authors declare that the EU funded this study under the LEARN/Lao MCNV Project (Number: DCI/SANTI/2014/342–306). The funder does not have any role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SP, DRE, MM, JEWB, and EPW designed the study and developed checklist. SP and MM provided training and analyzed data. MM, DRE and JEWB supervised the study and did data quality control. SP, DRE, JEWB, MM and PW drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Written informed consent to publish was obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Phommachanh, S., Essink, D.R., Wright, E.P. et al. Do health care providers give sufficient information and good counseling during ante-natal care in Lao PDR?: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 449 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4258-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4258-z