Abstract

Background

Multiple studies have investigated the outcome of integrated care programs for chronically ill patients. However, few studies have addressed the specific role hospitals can play in the downstream collaboration for chronic disease management. Our objective here is to provide a comprehensive overview of the role of the hospitals by synthesizing the advantages and disadvantages of hospital interference in the chronic discourse for chronically ill patients found in published empirical studies.

Method

Systematic literature review. Two reviewers independently investigated relevant studies using a standardized search strategy.

Results

Thirty-two articles were included in the systematic review. Overall, the quality of the included studies is high. Four important themes were identified: the impact of transitional care interventions initiated from the hospital’s side, the role of specialized care settings, the comparison of inpatient and outpatient care, and the effect of chronic care coordination on the experience of patients.

Conclusion

Our results show that hospitals can play an important role in transitional care interventions and the coordination of chronic care with better outcomes for the patients by taking a leading role in integrated care programs. Above that, the patient experiences are positively influenced by the coordinating role of a specialist. Specialized care settings, as components of the hospital, facilitate the coordination of the care processes. In the future, specialized care centers and primary care could play a more extensive role in care for chronic patients by collaborating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Healthcare today is characterized by a graying population. Specifically, this trend implies larger proportions of people suffering from illnesses with a chronic course and high impact on their daily lives [1]. Beyond that, rapidly growing medical knowledge and technological innovation enables more diagnostic and treatment possibilities. Due to these trends, there is a steady increase in healthcare complexity, and coordination has become a high-priority need in healthcare systems and management [1, 2]. As chronic patients require long-term, complex healthcare responses, optimal collaboration and coordination between professionals is necessary to provide integrated and continuous care for the chronically ill [1, 2]. A major element in chronic care is the interface between hospitals, primary care providers, and community-based services [3]. A lack of coordination and integration here can cause care processes to become incoherent, redundant, and error-prone. For example, the period of discharge from hospital to home is known to be sensitive to suboptimal coordination of care, introducing concerns with respect to the quality of care [4, 5]. Hospitals will need to work closely with community partners to adequately follow-up chronic patients and to prevent avoidable hospital readmissions [6]. Forster et al. [7] reported on the frequency and severity of adverse effects following hospital discharge. Beyond this, as the applicable technology and technical knowledge grow, more services will be provided outside the hospital. Hence, hospitals will need to shift their focus from the initial role of acute care to a new additional role in chronic care.

Reducing acute hospital care for people with long-term conditions has become an important element of health policy, as governments aim to contain escalating healthcare costs [8]. Avoiding acute episodes in this group of patients is a goal in itself, and this purpose can be achieved by better chronic care. Inclusion of the acute care setting in chronic illness management is essential, because even when managed ideally, patients with chronic illnesses are frequently admitted to hospital [9]. Most experts believe that it is preferable to manage chronic disease in the ambulatory setting [9]. For example the Chronic Care Model entails changes to the health care system, mainly in the ambulatory setting, to support the development of informed, activated patients and prepared health care teams to improve outcomes [10]. In other initiatives, physician associations and employer groups have joined forces to promote the development of patient-centered medical homes in the ambulatory setting to improve the care of complex chronic illness [11, 12]. However, while advocates of outpatient chronic care argue that acute hospital care can be avoided [13], hospitals will continue to play a key role in chronic care, as most chronic conditions are characterized by acute exacerbation requiring admission. Hospitals will thus remain responsible for specific interventions [8]. Strategies need to be devised to engage hospitals and assist them in adopting innovative chronic care models not to the exclusion of, but in addition to, ambulatory care approaches. As such, hospitals will remain indispensable, but will occupy a less dominating position in the case of the chronic care patients than they employ for acute care.

Although several articles can be found regarding coordination and integrated care programs for chronically ill patients [14], too little attention has been devoted to the systematic evaluation of the current evidence for these initiatives from the perspective of hospitals and their future roles.

This article aims to examine current evidence and provide a structured, comprehensive overview of the role of hospitals in the downstream coordination and follow-up care of chronically ill patients.

The next section describes the search strategy employed, as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The results are presented from four distilled perspectives of chronic disease management. The results are then integrated into the discussion, and the implications of our findings for research, practice, and policy are addressed.

Methods

Data sources

This study draws upon an analysis of the literature from a systematic review perspective. The Embase, Pubmed, Cinahl, EBSCO, and Web of Science databases, along with the Cochrane Library, were searched for relevant studies. The searches were conducted in March 2016. The concepts of chronic illness, integrated or transitional care, and hospitals were combined into a standardized search string using MeSH and non-MeSH entry terms:

(“delivery of health care, integrated” OR “transmural care” OR “chain care” OR “chain of care” OR “care chain” OR “care continuity, continuum of care” OR “case management” OR “disease management” OR “health network” OR “care network” OR “patient care management” OR “long term care” OR “transitional care” OR “discharge care” OR “hospital discharge” OR “coordination of care” OR “care coordination”) AND (hospitals OR “inpatient care” OR “inpatient setting” OR hospitalization) AND (“chronic disease” OR “chronic illness” OR “chronically ill” OR “chronic condition” OR comorbidity OR multimorbidity OR “multiple chronic conditions”). The initial search strategy was validated using a selection of key papers known to the authors.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our review focused on English-language papers published between 1st January 1995 and 28th February 2016. This time frame was chosen since integrated care has become an increasingly important focus of attention in healthcare literature from 1995 on [15]. In the 1990s, integrated delivery systems were set up to focus on better care coordination as a means of improving quality and reducing cost, even though most of these systems failed to deliver savings [15]. The integrated (or organized) delivery system—the first notion resembling integrated care—was described in 1994 by Shortell et al. [15, 16]. This resulted in an increased interest in academic research on integrated care, with an increasing number of publications appearing after 1995.

Only empirical quantitative and qualitative research investigating the role of hospitals in the care of chronically ill patients was included. We excluded articles unrelated to hospitals, theoretical and conceptual analysis, abstracts of meetings, review articles, editorials, and letters. Studies set in community or hospice settings, psychiatric care, or children’s care were also excluded due to the specialized nature of the settings. Finally, since studies investigating or describing individual in-hospital programs without accentuating the ‘integration’ factor cannot demonstrate the role in the continuity of care, these studies were also excluded.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently searched for relevant studies using the standardized search strategy described above. The selection of studies was determined through a two-step procedure. First, the search results were filtered by title and abstract, and then narrowed down according to the formal inclusion and exclusion criteria. This removed many duplicates and references to nonempirical studies. The remaining studies were selected for full-text retrieval and underwent critical quality appraisal. In the case of noncorresponding results, consensus was sought through consultation with a third reviewer. In addition, the reference lists of relevant publications were screened and a forward citation track was applied.

Critical quality appraisal

Following Hawker et al. [17], all relevant studies were appraised using a global unweighted score based on critical appraisal to grade the accepted studies. Nine quality criteria were used and checked for every article (see Table 1). Articles with seven or more of the nine criteria were defined as high-quality studies. Studies fulfilling four, five, or six criteria were classified as medium-quality. Articles matching fewer than four criteria were described as low-quality. Each reviewer graded the empirical studies independently. Disagreements between the two raters were solved by a consensus discussion involving a third reviewer. An additional assessment of the manuscripts using an intervention on the basis of the EPOC review criteria was conducted (http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors) (Table 2).

Results

Literature search

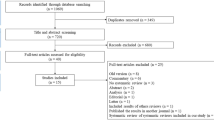

Our literature search initially yielded 11,220 unique candidate articles following duplication removal (Fig. 1). Their potential relevance was examined based on their titles, and 642 were selected for abstract retrieval. On the basis of an abstract review, 448 articles were excluded from further review. After this step, the 194 references that appeared to meet the study eligibility criteria were reviewed thoroughly in full text. Several articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion of paper in this stage where among others: not empirical research, no hospital included, not the target group, language (e.g. article just in Spanish) and systematic literature reviews. As several articles did not meet the inclusion criteria and, after consensus had been reached between the reviewers, 21 articles were included. The bibliographical references to these studies were examined to collect additional studies that had not been included in the records identified in the database search. In this way, 11 additional studies were included. As no additional studies were identified through their reference check this resulted in a final sample of 32 studies in the review.

Quality appraisal

Table 1 summarizes the quality appraisal scores. Thirty-one studies had a score of seven or more, and can be considered high-quality papers that show a rigorous methodological approach. One paper was qualified as medium quality, which indicates good methodological rigor. Table 2 summarizes the risk of bias for intervention studies (namely randomized control trails, non-randomized controlled trails and controlled before-after studies).

Description of studies

The studies originated from many different countries, showing the international relevance of this topic. Most were from the United States (n = 10) and two were from Canada. Fourteen studies are carried out in Europe (United Kingdom: n = 5; Spain: n = 3; The Netherlands: n = 3; Sweden: n = 1; Ireland: n = 1; and Italy: n = 1). Three studies were carried out in Asia, two in Australia, and one in Africa.

The selected studies differed in a number of characteristics (Table 3). First, they involved different types of patient groups: patients with heart failure, patients with diabetes mellitus, patients with rheumatoid arthritis, patients with cardiovascular disease, stroke patients, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and patients with chronic illnesses in general. In evaluating the results, no notable differences were found between the clinical areas. Second, several study designs can be distinguished: the majority of the studies applied a randomized control design comparing discharge and follow-up interventions with routine care for chronically ill patients. Qualitative research methods were used to examine patients’ experiences in the continuum of care. Furthermore, case studies and retrospective database analysis were employed. Third, multiple outcome measures were used, such as variables related to clinical outcomes (e.g., readmission at 30 and 90 days and 1 year; time to hospital readmission; additional hospital admissions; length of stay; mortality at 90 days and 1 year; event-free survival; emergency department presentations), determinants of the level of knowledge of the therapeutic regime (e.g., guideline adherence as well as patient adherence); quality of life (e.g., Activities of Daily Living scores), patient satisfaction and costs (e.g., average cost per patient treated). As can be seen, the universe of articles collected was quite diverse and the articles differed in methodology and intent.

By performing content analysis of the studies, four different themes (perspectives) emerged from the articles. For the analysis phase all the selected articles where read through making a descriptive evaluation of the literature. Notes were made to mark relevant information in the papers. Data was fractured and analyzed directly, initially through open coding for the emergence of a core category. Consequently, different items were categorized. The author identified whether or not the categories could be linked any way and listed them in four major themes. Finally, two researchers independently allocated the articles to the different groups. In the case of noncorresponding results, consensus was sought through consultation with a third reviewer.

The majority of the articles (15, 47%) described a transitional care intervention originating from a hospital to enhance the discharge and follow-up process for chronically ill patients. Closely related was the perspective of specialized settings providing care after hospital discharge; this was studied in four (12%) articles. A third perspective, found in eight (25%) articles, involved looking at outcomes in hospital care versus nonhospital care for chronically ill patients. The final perspective was the experiences and expectations of chronically ill patients towards the continuity of their illness during or after hospitalization (5, 16%). The results in each of these dimensions will be described separately (see also Tables 3 and 4).

Transitional care interventions

A total of 15 papers evaluated the effectiveness of transitional care interventions initiated within the hospital. The interventions consisted of comprehensive transitional care interventions with different steps. Patients were identified during their inpatient stay and followed up during and after discharge. These follow-ups were coordinated by transition coaches (such as specialized nurses and case managers). Besides the follow-up, most interventions included varying assistance, such as medication self-management, patient-centered records, red flags indicative of the patient’s condition, and education programs and access to outpatient clinics for the patients after hospitalization [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. All but one [19] compared the interventions with control groups of patients receiving the usual care.

Several authors demonstrated lower readmission rates for the intervention patients than for control subjects [21, 23,24,25,26, 28,29,30] and lower hospital costs [24, 29, 31]. This in contrast with Abad-Corpa et al. [18], Brand et al. [32], Cline et al. [31], Linden & Butterworth [20], and Ledwidge et al. [22], who found no difference between the control and intervention groups in readmission rates. Other cited positive outcomes for the intervention patients included high levels of confidence in managing their condition and understanding their medical regimen [28], significant improvements in quality of life after discharge [18, 26], and patient satisfaction [25, 26]. However, Farrero et al. [24] and Adab-Corpa et al. [18] could not confirm this higher patient satisfaction.

On organizational level, Baldwin et al. [19] described a positive change in hospital culture since the beginning of the transitional care program (e.g., more dialogue between healthcare providers). However, Brand et al. [32] identified major issues (such as patient factors and local system issues like inadequate integration of the program, inadequate stakeholder understanding of the program, inadequate clerical support resources, and inadequate integration of documentation) that have an impact on the effectiveness and sustainability of the transitional care model.

Jeangsawang et al. [27] compared the effect of transitional care programs between three different type of nurses—namely, advanced practice nurses (APNs), expert-by-experience nurse, and novice nurses. Only the satisfaction of family members in favor of the APNs was significant. The APNs were seen as useful healthcare providers in a complex healthcare system.

Specialized care settings

Three studies examined the effect of interventions at a heart failure clinic compared to usual care [34,35,36] (Table 4). In these studies, a heart failure clinic was designed, as a multiple specialty, short-term management program for patients with heart failure, implying comprehensive hospital discharge planning and close follow-up at these heart clinics after hospital discharge. These heart clinics are thus components of the hospital. Overall, the results for such clinics showed positive effects in terms of lower hospitalization duration, fewer hospital readmissions, lower mortality rates, and improvement in clinical outcomes (e.g., left ventricular ejection fraction) [34,35,36]. The quality of life improved and the cost of care were reduced in the intervention group [35, 36]. Similar results were found in the study of Hanumanthu et al. [37]. They examined whether a heart failure program managed by physicians with expertise in heart failure could improve hospitalization rates and financial outcomes; they found positive effects in terms of reductions in hospitalization after initiation of the program.

Hospital care versus nonhospital care

Our review identified three articles that compared the effectiveness of long-term institutional care versus home-based care (Table 4). The findings were mixed; on one hand, Ciu et al. [38] stated that caring for patients in their own homes was more expensive and less effective. On the other hand, Moalosi et al. [39] found that home-based care is more affordable and reduced costs, while Ricauda et al. [40] found a lower incidence of hospital readmissions and shorter length of stay for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) geriatric patients in geriatric home hospitalization wards than for patients at general medical wards.

Additionally, four papers studied follow-ups for chronically ill patients in secondary versus primary care (Table 4). The results of Luttik et al. [41] showed that the number of readmissions tended to be higher in the primary care group than in the heart failure clinic group; Sadatsafavi et al. [42] found that patients in secondary care showed evidence of more appropriate treatment; however, they could not demonstrate reductions in cost or readmissions. However, patient satisfaction was higher for patients in follow-ups for cancer care with their general practitioner than in hospital outpatient clinics [38, 43]. Shi et al. [33], found that hospitals did not provide a higher quality of care in terms of coordination of medication, referrals, and services received, compared to rural health stations.

Finally, one paper evaluated the improvement achieved by a short inpatient treatment program for rheumatoid arthritis versus outpatient care [44], and showed a significantly greater improvement in clinical outcomes for the inpatient group than for the outpatient group [44].

Experiences and expectations of patients

Some other important variables identified in five of the articles are the patients’ experiences and values with respect to the continuity of care in the context of long-term conditions (Table 4). Naithani et al. [45] described four dimensions of continuity of care experienced in diabetes: (1) longitudinal continuity (receiving regular reviews with clinical testing and advice over time), (2) relational continuity (having a relationship with one care provider who knew and understood the patient, was concerned and interested, and who took the time to listen and explain), (3) flexible continuity (flexibility of service provision in response to changing needs or situations), and (4) team and crossboundary continuity (consistency and coordination between different members of staff and between hospital and general practice or community settings). The study revealed that most problems occurred at transition points; thus, with a lack of crossboundary continuity between sites or between providers or a lack of flexibility in coordination when there are major changes in the patient’s needs. Cowie et al. [46] showed that relational continuity was positively correlated with long-term specialist-led care, illustrating that patients need continuity; this can even originate from a hospital (i.e., specialist-led care). They also demonstrated that access to care and flexibility issues were important barriers and facilitators of continuity. Investigating the perceptions of quality of care by chronically ill patients who require acute hospital stays, Williams [47] revealed three themes: (1) patients perceive poor continuity of care, especially for comorbidities, (2) it is inevitable that something goes wrong during acute care, and (3) chronic conditions persist after discharge. The combinations of chronic illness and treatment affected the patients’ experiences of acute care and recovery following discharge. Ireson et al. [48] looked at the quality of information received by patients and the relationship between this information and trust in the physician. Most patients received good explanations for the reason for a specialist visit, but felt unprepared about what to expect. Beyond that, specialists give good explanations of diagnosis and treatment, but not about follow-ups to treatment. Trust in the specialist correlated highly with good explanations of diagnosis, treatment, and self-management [48].

Discussion

In care delivery models (such as the Chronic Care model) the importance of the hospital in chronic illness management is recognized [9]. This also holds for the fact that attending to acute illness episodes is integral to the delivery of chronic illness care. As such, including elements from the hospital sector in chronic illness management is essential. This paper provides an overview of the empirical literature on the role of hospitals in chronic disease management. Our aim was to synthesize the available, somewhat fragmentary, evidence. This study outlines different types of clinical fields, diverse methodologies, and multiple outcome measures. The results are structured following four large domains: the impact of transitional care interventions, the role of specialized care settings, the comparison of inpatient and outpatient care, and the effect of chronic care coordination on the experience of patients. The type of integrated care interventions and the effects varied across the different studies; however, some important insights follow from the published results.

Most of the integrated care research focused on the outcome of integrated care programs. These integrated care programs seem to have positive effects on the quality of care. However, there are widely varying definitions and components of integrated care programs [15], while the specific role of the hospitals is often neglected. Most of the integrated care programs in our systematic review, which thus focused on the role of the hospital, included structured clinical follow-ups and case management, often combined with self-management support and patient education. A large number of the articles show that these integrated care programs originating from the hospital have positive effects; like the reduction of hospital readmission [21, 23,24,25,26, 28,29,30] and lower costs [24, 29]. Note, however, that we did not include studies with integrated care programs originating from outside the hospitals, so we cannot compare these programs.

However, there are also articles demonstrating that not all integrated care interventions are successful [18, 20, 22, 31, 32] and that there are impeding factors, such as the difficulty of implementing integrated care programs [32], thus showing the complexity of integrated care for chronically ill patients. This has also been described by Cramm et al. [49] who showed that the implementation of transition programs requires a supportive and stimulating team climate to enhance the quality of care delivery to chronically ill adolescents.

The transition of care for the chronically ill also impacts patient perceptions [25, 26]. The coordinating role of a specialist influences the patient experience in a positive way [19, 27]. Specialists input -to diagnosis, initial assessment, and treatment- is essential. A chronic condition may well have large implications, and specialist expertise ensures optimum treatment and offers the best chance of maintaining health. As such, hospitals can be an entry and follow up point for the chronically ill patient.

Continuity of care is very important. This finding supports the necessity for more research on hand-overs in healthcare processes [50]. Other studies show the importance of case managers [51] and patient care teams [52] in transitional care interventions. In this literature review, we did not investigate who is required to take the lead in the coordination of care for the chronically ill. However, different roles are observed for hospitals. Hospitals play an important role in the coordination of transitional processes, and our results show that this coordination can be managed by case managers (such as advanced nurses) from within the hospitals; the role of a specialized case manager or coordination program was identified as highly important by the patients [37, 46]. As a result, hospitals should be organized into process-oriented teams (physicians and nurses) and seek to coordinate integrated care for chronically ill.

General practitioners were also identified as playing coordinating roles [43, 46]. However, it seems that primary care is perceived by the patient as less efficient and of lower quality than secondary care, above that, specialized care settings provide better results compared to primary care [41, 42]. But, as we saw, primary care can also be important in integrated care programs [33, 43]. As such, an increase in integrated care arrangements might introduce a shift of some tasks guided by hospitals to either primary care or more specialized care services. Hospital units with a focus on specific pathologies might not only break the current boundaries of medical departments but also challenge the boundaries between the different healthcare partners. Such ‘vertical networks’ (collaborations between organizations with different service offerings) can improve coordination and thus service delivery for the chronically ill [53]. Further research on this topic, mainly on how this collaboration can be organized, is recommended.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first comprehensive attempt to evaluate the role of the hospital for patients with chronic illness. However, the study has several potential limitations. The most obvious is the relatively small sample size of articles evaluating the specific role of hospitals in chronic disease management. Longitudinal studies constitute an important avenue for future research. Beyond that, some articles could have been missed, as we specifically targeted those looking at the role of hospitals in chronic disease management, rather than in chronic disease management in general. We did not focus on studies solely studying elderly or pediatric patients, as in these groups different actors are involved than in the regular adult care. However, studies focusing on elderly are extremely important since the role of the hospital in the coordination of care and follow-up for elderly might be considerable. Hence, further research in the domain elderly care is recommended. Above that, the results are based on a limited number of search terms and as MeSH terms were used, some papers could have been excluded from the results as the process of indexing papers is not immediate.

Additionally, the review did not capture gray literature, publically available literature not published in peer reviewed journals, and thus not all relevant articles may have been included. Another limitation of the study is that the heterogeneous nature of the studies (in terms of interventions, patient population, types of outcomes, and settings) and the methodological deficiencies identified did not permit the use of formal statistical techniques, such as meta-analysis [54]. Meta-analysis makes it possible to correct for random errors, though not for systematic errors or influencing factors, such as study setting or patient population. Therefore, good descriptions of the studies and interpretation of the results, as provided in our review, are still necessary. Caution should be employed in generalizing the conclusions of our review.

Conclusion

In the view of the changing healthcare context and the dehospitalization of care, we have addressed an important topic. Hospitals play an important role in transitional care interventions and in the coordination of care. Specialized care settings also invest in the coordination of these processes. In the future, specialized care centers and primary care will play a more extensive role in the care for chronic patients and will have to collaborate.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living Scores

- APN:

-

Advanced practice nurses

- CHF:

-

Chronic Heart Failure

- CMM:

-

Community Nursing Care

- CNS:

-

Clinical Nurse Specialist

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- H:

-

High

- HCP:

-

Home-care program

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- M:

-

Medium

- MLHFQ:

-

Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

References

Glouberman S, Mintzberg H. Managing the care of health and the cure of disease, part I: differentiation. Health Care Manag Rev. 2001;26(1):56–69. discussion 87–59.

Glouberman S, Mintzberg H. Managing the care of health and the cure of disease, part II: integration. Health Care Manag Rev. 2001;26(1):70–84. discussion 87–79.

Ludecke D. Patient centredness in integrated care: results of a qualitative study based on a systems theoretical framework. Int J Integr Care. 2014;14:e031.

Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE, Singa RM, Shepperd S, Rubin HR. Comprehensive discharge planning with postdischarge support for older patients with congestive heart failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1358–67.

Windham BG, Bennett RG, Gottlieb S. Care management interventions for older patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9(6):447–59.

Cunningham FC, Ranmuthugala G, Plumb J, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J. Health professional networks as a vector for improving healthcare quality and safety: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(3):239–49.

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–7.

Steiner MC, Evans RA, Greening NJ, Free RC, Woltmann G, Toms N, Morgan MD. Comprehensive respiratory assessment in advanced COPD: a ‘campus to clinic’ translational framework. Thorax. 2015;70(8):805–8.

Siu AL, Spragens LH, Inouye SK, Morrison RS, Leff B. The ironic business case for chronic care in the acute care setting. Health Aff. 2009;28(1):113–25.

Wagner EH, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;6:64–78.

Arvantes J. Medical home gains prominence with AAFP oversight. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(1):90–1.

Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM. A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):953.

Hernandez C, Jansa M, Vidal M, Nunez M, Bertran MJ, Garcia-Aymerich J, Roca J. The burden of chronic disorders on hospital admissions prompts the need for new modalities of care: a cross-sectional analysis in a tertiary hospital. QJM. 2009;102(3):193–202.

Ouwens M, Wollersheim H, Hermens R, Hulscher M, Grol R. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(2):141–6.

Sun X, Tang W, Ye T, Zhang Y, Wen B, Zhang L. Integrated care: a comprehensive bibliometric analysis and literature review. Int J Integr Care. 2014;14:e017.

Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA. The new world of managed care: creating organized delivery systems. Health Af (Millwood). 1994;13(5):46–64.

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Quale Health Res. 2002;12(9):1284–99.

Abad-Corpa E, Royo-Morales T, Iniesta-Sanchez J, Carrillo-Alcaraz A, Jose Rodriguez-Mondejar J, Rosario Saez-Soto A, Carmen V-MM. Evaluation of the effectiveness of hospital discharge planning and follow-up in the primary care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clinic Nurs. 2013;22(5–6):669–80.

Baldwin KM, Black D, Hammond S. Developing a rural transitional care community case management program using clinical nurse specialists. Clin Nurse Specialist. 2014;28(3):147–55. 149p.

Linden A, Butterworth SW. A comprehensive hospital-based intervention to reduce readmissions for chronically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(10):783–92. 710p.

Rauh RA, Schwabauer NJ, Enger EL, Moran JF. A community hospital-based congestive heart failure program: impact on length of stay, admission and readmission rates, and cost. Am J of Manag Care. 1999;5(1):37–43.

Ledwidge M, Ryan E, O’Loughlin C, Ryder M, Travers B, Kieran E, Walsh A, McDonald K. Heart failure care in a hospital unit: a comparison of standard 3-month and extended 6-month programs. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(3):385–91.

Harrison MB, Browne GB, Roberts J, Tugwell P, Gafni A, Graham ID. Quality of life of individuals with heart failure: a randomized trial of the effectiveness of two models of hospital-to-home transition. Med Care. 2002;40(4):271–82.

Farrero E, Escarrabill J, Prats E, Maderal M, Manresa F. Impact of a hospital-based home-care program on the management of COPD patients receiving long-term oxygen therapy. Chest. 2001;119(2):364–9.

Williams G, Akroyd K, Burke L. Evaluation of the transitional care model in chronic heart failure. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(22):1402–7.

Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675–84.

Jeangsawang N, Malathum P, Panpakdee O, Brooten D, Nityasuddhi D. Comparison of outcomes of discharge planning and post-discharge follow-up care, provided by advanced practice, expert-by-experience, and novice nurses, to hospitalized elders with chronic healthcare conditions. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res Thail. 2012;16(4):343–60. 318p.

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min SJ, Parry C, Kramer AM. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the care transitions intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1817–25.

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S-J. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–8.

Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JJ, Davie AP, McDonagh TA, Murdoch DR, Petrie MC, Connolly E, Norrie J, Round CE, et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2001;323(7315):715–8.

Cline CM, Israelsson BY, Willenheimer RB, Broms K, Erhardt LR. Cost effective management programme for heart failure reduces hospitalisation. Heart. 1998;80(5):442–6.

Brand CA, Jones CT, Lowe AJ, Nielsen DA, Roberts CA, King BL, Campbell DA. A transitional care service for elderly chronic disease patients at risk of readmission. Aust Health Rev. 2004;28(3):275–84. 210p.

Shi L, Makinen M, Lee DC, Kidane R, Blanchet N, Liang H, Li J, Lindelow M, Wang H, Xie S, et al. Integrated care delivery and health care seeking by chronically-ill patients: a case-control study of rural Henan province, China. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:98.

Akosah KO, Schaper AM, Havlik P, Barnhart S, Devine S. Improving care for patients with chronic heart failure in the community: the importance of a disease management program. Chest. 2002;122(3):906–12. 907p.

Atienza F, Anguita M, Martinez-Alzamora N, Osca J, Ojeda S, Almenar L, Ridocci F, Valles F, de Velasco JA. Multicenter randomized trial of a comprehensive hospital discharge and outpatient heart failure management program. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6(5):643–52.

de la Porte PW, Lok DJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, van Wijngaarden J, Cornel JH, Zuithoff NP, Badings E, Hoes AW. Added value of a physician-and-nurse-directed heart failure clinic: results from the Deventer-Alkmaar heart failure study. Heart. 2007;93(7):819–25.

Hanumanthu S, Butler J, Chomsky D, Davis S, Wilson JR. Effect of a heart failure program on hospitalization frequency and exercise tolerance. Circulation. 1997;96(9):2842–8.

Chiu L, Shyu W, Liu Y. Comparisons of the cost-effectiveness among hospital chronic care, nursing home placement, home nursing care and family care for severe stroke patients. J Adv Nurse. 2001;33(3):380–6. 387p.

Moalosi G, Floyd K, Phatshwane J, Moeti T, Binkin N, Kenyon T. Cost-effectiveness of home-based care versus hospital care for chronically ill tuberculosis patients, Francistown, Botswana. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7(9 SUPPL 1):S80–5.

Aimonino Ricauda N, Tibaldi V, Leff B, Scarafiotti C, Marinello R, Zanocchi M, Molaschi M. Substitutive “hospital at home” versus inpatient care for elderly patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(3):493–500.

Luttik MLA, Jaarsma T, van Geel PP, Brons M, Hillege HL, Hoes AW, de Jong R, Linssen G, Lok DJA, Berge M, et al. Long-term follow-up in optimally treated and stable heart failure patients: primary care vs. heart failure clinic. Results of the COACH-2 study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(11):1241–8.

Sadatsafavi M, FitzGerald M, Marra C, Lynd L. Costs and health outcomes associated with primary vs. secondary care after an asthma-related hospitalization: a population-based study. Chest. 2013;144(2):428–35.

Grunfeld E, Fitzpatrick R, Mant D, Yudkin P, Adewuyi-Dalton R, Stewart J, Cole D, Vessey M. Comparison of breast cancer patient satisfaction with follow-up in primary care versus specialist care: results from a randomized controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(446):705–10.

Vliet Vlieland TP, Breedveld FC, Hazes JM. The two-year follow-up of a randomized comparison of in-patient multidisciplinary team care and routine out-patient care for active rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36(1):82–5.

Naithani S, Gulliford M, Morgan M. Patients’ perceptions and experiences of ‘continuity of care’ in diabetes. Health Expect. 2006;9(2):118–29.

Cowie L, Morgan M, White P, Gulliford M. Experience of continuity of care of patients with multiple long-term conditions in England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009;14(2):82–7. 86p.

Williams A. Patients with comorbidities: perceptions of acute care services. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(1):13–22.

Ireson CL, Slavova S, Steltenkamp CL, Scutchfield FD. Bridging the care continuum: patient information needs for specialist referrals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:163.

Cramm JM, Strating MMH, Nieboer AP. The role of team climate in improving the quality of chronic care delivery: a longitudinal study among professionals working with chronically ill adolescents in transitional care programmes. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005369.

Spruce L. Back to basics: patient care transitions. AORN J. 2016;104(5):426–32.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(6):64–78.

Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2000;320(7234):569–72.

Brown BB, Patel C, McInnes E, Mays N, Young J, Haines M. The effectiveness of clinical networks in improving quality of care and patient outcomes: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:360.

Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res. 2005;10 Suppl 1:6–20.

Dossa A, Bokhour B, Hoenig H. Care Transitions from the Hospital to Home for Patients with Mobility Impairments: Patient and Family Caregiver Experiences. Rehabil Nurs. 2012;37:277–85. doi:10.1002/rnj.047

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Stephen Mulraney for the language editing of the article.

Funding

The authors received no funding.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MDR, JT, and BM framed the research question. MDR and KDP searched independently for relevant studies and assessed the quality of the studies. MDR summarized the evidence. MDR and BM interpreted the findings. MDR, KDP, and KE were the major contributors to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

De Regge, M., De Pourcq, K., Meijboom, B. et al. The role of hospitals in bridging the care continuum: a systematic review of coordination of care and follow-up for adults with chronic conditions. BMC Health Serv Res 17, 550 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2500-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2500-0