Abstract

Background

The Better Health Outcomes through Mentoring and Assessment (BHOMA) project is a cluster randomized controlled trial aimed at reducing age-standardized mortality rates in three rural districts through involvement of Community Health Workers (CHWs), Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs), and Neighborhood Health Committees (NHCs). CHWs conduct quarterly surveys on all households using a questionnaire that captures key health events occurring within their catchment population. In order to validate contact with households, we utilize the Lot Quality Assurance Sampling (LQAS) methodology. In this study, we report experiences of applying the LQAS approach to monitor performance of CHWs in Luangwa District.

Methods

Between April 2011 and December 2013, seven health facilities in Luangwa district were enrolled into the BHOMA project. The health facility catchment areas were divided into 33 geographic zones. Quality assurance was performed each quarter by randomly selecting zones representing about 90% of enrolled catchment areas from which 19 households per zone where also randomly identified. The surveys were conducted by CHW supervisors who had been trained on using the LQAS questionnaire. Information collected included household identity number (ID), whether the CHW visited the household, duration of the most recent visit, and what health information was discussed during the CHW visit. The threshold for success was set at 75% household outreach by CHWs in each zone.

Results

There are 4,616 total households in the 33 zones. This yielded a target of 32,212 household visits by community health workers during the 7 survey rounds. Based on the set cutoff point for passing the surveys (at least 75% households confirmed as visited), only one team of CHWs at Luangwa high school failed to reach the target during round 1 of the surveys; all the teams otherwise registered successful visits in all the surveys.

Conclusions

We have employed the LQAS methodology for assurance that quarterly surveys were successfully done. This methodology proved helpful in identifying poorly performing CHWs and could be useful for evaluating CHW performance in other areas.

Trial registration

Identifier: NCT01942278. Date of Registration: September 2013.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although most low income countries including Zambia have adopted Primary Health Care (PHC), access to basic health care still remains a challenge [1, 2]. The WHO defines PHC as essential community-based health care that is universally accessible to individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations, is driven by community participation in identifying health issues and making decisions on appropriate solutions, and is sustained by the community [2, 3]. This approach often involves utilization of Community Health Workers (CHWs) as a community-based resource to address the immediate shortage of professional health workers [3]. This shortage of human resources is worst in rural areas, resulting in greater morbidity and mortality in rural communities [1, 4, 5].

Acknowledging the shortage of formally trained health workers, the Zambian National Health Strategy presently allows for standard training of volunteer CHWs to deliver basic community-based primary health care [5, 6]. Recently, the government embarked on a programme to provide formal training of CHWs for 1 year, after which they are employed by the government as part of the formally recognized health work force and return to serve their respective communities [6]. This approach is not unique to Zambia as many other low-middle income countries are also heavily dependent on CHWs to provide health services, especially in rural areas [6, 7]. Evidence suggests that this cadre of health workers is being used by several nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and civil societies globally [7–9].

To respond to the human resource challenges in rural Zambia, the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ) has been implementing a large health systems strengthening programme called Better Health Outcomes through Mentoring and Assessments (BHOMA), which leverages CHWs to improve service delivery [10]. Through BHOMA, CHWs were trained to work in the Out Patient Department (OPD) to screen patients and perform simple procedures such as checking vital signs and initiating patient record files. Some of the CHWs were trained to follow-up patients in the community for which they were trained on use of mobile phones for real-time electronic data capture and transmittal over the regular Global System for Mobile communications (GSM) network, which has been reported elsewhere [11]. The BHOMA data system tracks patients presenting to the OPD with clinical “danger signs” and for those who do not return on appointed review dates. Reminder text messages were sent to the respective CHW covering the communities where the patient registered as a permanent residence when giving their demographic information during household visits and at the health facility registration department. The CHWs also undertake quarterly cross-sectional household visits collecting key health events within their catchment population. Each health facility has a CHW supervisor to oversee activities and ensure that appropriate roles and tasks are achieved [10, 11]. The use of mobile phones elsewhere by CHWs has proven to improve community case management and collection of complete, timely, and precise health data for future research in rural areas of Africa [11].

To provide quality assurance on CHW performance, the BHOMA project employed the Lot Quality Assurance Sampling (LQAS) methodology [12]. LQAS was originally developed to control the quality of output in industrial production processes and later on used for conducting health surveys [13, 14]. LQAS has emerged as a useful tool in public health to identify low-performing program areas and to monitor developing countries’ health programs at different levels of the health care delivery system [13–15]. In Rwanda, LQAS was successfully used for data quality assessment of the CHW program in the documentation of key demographic and health indicators leading to improved quality of data collection [16].

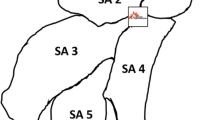

This paper reports application of the LQAS approach to monitor CHW performance in relation to completing quarterly household surveys and health information sharing with the target communities, in Luangwa district, which is one of rural districts in Zambia.

Methods

Between April 2011 and December 2013, seven health facilities in Luangwa District were enrolled into the BHOMA project LQAS survey study. Each health facility catchment area was divided into geographical zones, where each zone included up to a maximum of 300 households. Existing and new CHWs from within the communities were recruited through established community participatory methods by engaging traditional leaders and neighborhood health committee members from all villages within the zone to ensure representativeness for all zones. Using the existing structures in each community, both existing and new CHWs were recruited following open advertisement and interviews. Selected CHWs met minimum qualifications of reaching grade 7 and ability to read and write.

A total of 70 candidate CHWs were interviewed from which 33 were recruited according to the number of the district zones for the study. Of these 14 were female (age range 18 to 35) and 19 were male (age range 20 to 48). The median educational level among CHWs was grade 12 (range 7–12); see Table 1.

The CHWs underwent project-specific orientation on a “community care” package. The training package included data entry using mobile phones and collection of demographic data, age bands, tracking and recording of mortalities. They were also taught on how to collect data on HIV, pregnancy, immunizations, and were to conduct various health-related topics. CHWs conducted monthly household surveys with the goal of reaching all households in their respective zones each quarter and thereafter submit electronically the data collected to the data management team based at the BHOMA central office in Lusaka. If they found a patient with a life-threatening condition or a clinical “danger sign”, they were trained to provide start doses of basic drugs from the CHW drug kit such as paracetamol and oral rehydration salts and then refer the patient to the nearest heath centre. Clinical “danger signs” include failure to drink or breastfeed, continuous vomiting, convulsions, lethargy/unconsciousness, chest in-drawing, severe shortness of breath, severe bleeding, and severe palmer pallor. The danger signs were classified according to the Zambia Ministry of Health integrated management of childhood illnesses (IMCI) classification guidelines. Pregnant women who had not started antenatal care were also referred to the maternal child health facility.

As part of quality assurance process, CHW supervisors were trained to coordinate the activities of CHWs and to use the LQAS survey questionnaire (see Additional file 1) to confirm CHW household visitation. Based on the households visited by CHWs in the previous quarter, the data management team at the BHOMA central office in Lusaka generated a random list of sampled households according to LQAS methodology [13].

The BHOMA study was reviewed and approved by both the University of Zambia Biomedical Ethics and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Ethics Committees.

Data collection

In each of the selected zone, 19 households were sampled by the CHW supervisors using a standardized questionnaire to be completed by either the head of the household or any member above 16 years as listed in Additional file 1. A sample size of 19 provides an acceptable level of error for decision-making by managers; at least 90% of the time, it identifies areas that have reached the set target or below the average coverage of the programme [17]. Since LQAS uses the binomial formula to calculate smaller samples and to come up with a decision criteria for grouping CHWs by their performance using a three triage assessment system; adequate, inadequate and very inadequate [15]. In this study, the same criteria was used to assign the CHW to the triage system and these were; coverage as been adequate if 75% or more of the targeted households were visited, inadequate if the coverage was between 50 and 75% and very inadequate if 50% or less. For instance in a sample of 19 households if only five or fewer have not been visited, then the CHW is said to have provided adequate coverage. If more than five households have not been visited, the CHW performance is considered as inadequate.

The CHW supervisors validated the data by counterchecking the unique household identity number and a summary of the health information discussed. Once the questionnaires were completed, they were submitted to the district study team for further data completeness checks before forwarding the forms to the data management team at the central office in Lusaka. CHW coverage performance was assessed by confirming physical visitation of a CHW to each household listed on the quarterly sample within each zone and delivery of health information on at least one health topic. A threshold was set apriori at 75% as the minimum standard for coverage.

Data analysis

To use LQAS decision rules, the study applied two rules for analysis;

-

1.

Define the performance standards for the survey coverage under the study using the three-part triage system.

-

2.

Develop a decision rule that states the maximum number of households which have not been visited during the intervention allowed in the LQAS. Any number greater than this threshold results in a CHW performance as being inadequate. In this example if five or fewer households are not visited by the CHW, the performance is adequate. If six or more households are not visited, the CHW performance is considered inadequate.

Thus the LQA sample size depends on performance standards, the classification error and the number of permissible error and all of them are interrelated. A detailed theory can be found elsewhere [15].

Data was collected on paper and captured on a CHW LQAS access database by the data management team at the study central office in Lusaka. The variables analyzed were the mean performance of households % visited in each of the survey round and also the frequency of at least one health topic being discussed by the CHWs. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics. Chi-squared tests were used for testing associations. ANOVAs were used to compare mean performance between CHWs. Each CHW performance was evaluated and assigned a performance score. Mean performance scores were computed for all the CHWs as a sum of total households visited by each CHW/total households to be sampled × 100 as determined by the data management team at the central office in Lusaka.

Results

CHW household visitation coverage

The household visits by the CHW were an important task that needed to be monitored by the CHW Supervisors. The LQAS shows that the household coverage was adequate in most of the rounds except in rounds 1 and 7 were the performance was inadequate (five of the 33 CHW) at two primary care facilities and needed improvement and mentorship.

The 33 zones had a total of 4,616 households. Each household was visited every quarter, resulting in 32,212 visits during the 7 surveys. Between 355 and 558 households were visited during each round of the LQAS survey, and CHW supervisors performed an average of 24 LQAS visits following each survey round. The mean performance of the CHWs was 94.9% (range 89.0–97.9%); round 1 had the lowest scores while round 6 had the highest scores as summarized in Table 2. There was no empiric evidence of the CHWs not visiting the households as the 75% benchmark was always met; rather, all sites trended over rounds toward increased CHW performance (p = 0.0014).

No difference in performance was found among the CHWs when their sex or educational attainment level was considered. Of note, at one site where one CHW attained only grade 9 level, LQAS scores were consistently as high as those in another site where all the CHWs had reached grade 12.

Health topics discussed

Households reported the following health education topics being discussed by CHWs during their visits in descending order: malaria, HIV/AIDS, other, diarrhea, family planning, water and sanitation, TB, child health, STIs and pregnancy. Malaria was the most discussed topic in every round as seen in Fig. 1 (Health topic discussed per round by CHWs). This is attributed to the high incidence of malaria cases recorded in most of the primary care facilities and also the district being in a valley and surrounded by two rivers.

Discussion

LQAS provided an objective assessment of CHW performance regarding household visitation rate and confirmation of key health information delivered at the household level. In this study, LQAS demonstrated consistent household visits by CHWs and hence validated its applicability in our settings for monitoring CHW performance. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have used LQAS to monitor CHW performance [18]. Two major additional findings from this study were (1) the confirmed CHW household visitation rate demonstrated a positive trend, increasing over time, and (2) the pattern of topics discussed was consistent with the burden of disease as captured through the OPD attendances at the health facility and common illnesses that were identified in the CHW zones. LQAS improved accountability of CHWs (through the requirement of providing information on their performance) and enabled continuous feedback on their performance. Through both pathways, LQAS proved an important mechanism for monitoring household visitations.

In low- and middle-income settings, CHWs play a critical role in health care provision, and objective assessment of their performance is key. This is particularly important in countries like Zambia where the government is expanding involvement of CHWs through a training programme that results in a formal civil service job such as the Community Health Assistant (CHA) [6].

District planners can evaluate CHW data quality through LQAS to identify targeted priority areas for investing resources [17, 19, 20]. LQAS was easy to implement as it did not require complicated epidemiological or statistical designs and was manageable in the field. LQAS also proved to be a powerful performance appraisal tool offering project supervisors a method of identifying both well- and poorly-performing workers and tracking their performance improvements [19–21].

In the BHOMA project, the opportunity for routine feedback on performance following each round was found to be a key improvement factor; CHWs understood well the use of the monitoring tool and were aware that poor performance would not go unnoticed. This finding is consistent with previous literature demonstrating that LQAS as a monitoring tool results in improved health outputs and outcomes including underperforming areas [22–24].

A limitation of our study was that we were not able to objectively assess any correlations between improved CHW performance and improvements in the quality of care at individual PHCs or any impact on morbidity or mortality, which were the key objectives of the main project. With an objective impact assessment, the effectiveness of CHWs should also be conducted with the LQAS methodology providing useful individual and zonal level performance data. These data are likely to be essential for informing any national scale up considerations.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that supervisors can feasibly monitor CHW performance through regular LQAS surveys. This methodology is not complicated to design, implement, or monitor as demonstrated by its application in one of the most rural and hard-to-reach areas of Zambia. We recommend its broader application for validating surveys and routine healthcare programmes.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variation

- BHOMA:

-

Better Health Outcomes through Mentoring and Assessments

- CHA:

-

Community health assistant

- CHW:

-

Community health worker

- CIDRZ:

-

Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- ID:

-

Identity number

- IMCI:

-

Integrated management of childhood illnesses

- LQAS:

-

Lot quality assurance sampling

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- NHC:

-

Neighbourhood health committee

- OPD:

-

Outpatient department

- PHC:

-

Primary health care

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- TBA:

-

Traditional birth attendants

References

Lehmann U, Damme WV, Barten F, Sanders D. Task shifting: the answer to the human resources crisis in Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:49. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-7-49.

Lindsey E, Sheilds L, Stajduhar K. Creating effective nursing partnerships: An approach to community based action. Nurs Outlook. 1999;45(1):23–6.

Kane SS, Gerretsen B, Scherpbier R, Poz MD, Dieleman M. A realist synthesis of randomized control trials involving use of community health workers for delivering child health interventions in low and middle income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:286.

Javanparast S, Baum F, Labonte R, Sanders D, Rajabi Z, Heidari G. The experience of community health workers training in Iran: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:291.

National Health Strategic Plan: 2011–2015. http://www.mcdmch.gov.zm/content/national-healthstrategic-plan-nhsp-2011-2015.

Zulu JM, Kinsman J, Michelo C, Hurtig A. Developing the national community health assistant strategy in Zambia: a policy analysis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:24.

Braun R, Catalani C, Wimbush J, Israelski D. Community Health Workers and Mobile Technology: A Systematic Review of the Literature. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65772. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065772. Accessed 9 Oct 2014.

Gilmore B, McAuliffe E. Effectiveness of community health workers delivering preventive interventions for maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:847.

Makaula P, Bloch P, Banda HT, Mbera GB, Mangani C, Sousa A, et al. Primary health care in rural Malawi - a qualitative assessment exploring the relevance of the community-directed intervention approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:328.

Stringer JSA, Taylor-Chisembele A, Chibwesha CJ, Chi HF, Ayles H, Manda H, et al. Protocol-driven primary care and community linkages to improve population health in rural Zambia: the Better Health Outcomes through Mentoring and Assessment (BHOMA) project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S7.

Schutter L, Sindano N, Theis M, Zue C, Joseph J, Chilengi R, et al. A mobile phone-based, community health worker program for referral, follow-up and service outreach in rural Zambia: outcomes and overview. Telemed E Health. 2014;20(8):721–8. doi:10.1089/tmj.2013.0240. Accessed 17 December 2014.

Tumusiime DK, Agaba G, Kyomuhangi T, Finch J, Kabakyenga J, Macleod S. Introduction of mobile phones for use by volunteer community health workers in support of integrated community case management in Bushenyi District, Uganda: development and implementation process. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14 Suppl 1:S2.

Lanata CF, Black RE. Lot quality assurance sampling techniques in health surveys in developing countries: advantages and current constraints. Health Serv Res. 1991;44(3):133–9. World health statistics quarterly.

Mushtaq MU, Majrooh MA, Ullah ZMS, Akram J, Siddiqui AM, Shad MA, et al. Are we doing enough? Evaluation of the Polio Eradication Initiative in a district of Pakistan’s Punjab province: LQAS study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:60.

Pezzoli L, Conteh I, Kamara W, Gacic-Dobo M, Ronveaux O, Perea WA, et al. Intervene before leaving: Clustered lot quality assurance sampling to monitor vaccination coverage at health district level before the end of a yellow fever and measles vaccination campaign in Sierra Leone in 2009. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:415.

Valadaz JJ, Diprete Brown L, Varges WV, Morley D. Using lot quality assurance sampling to assess measurements for growth monitoring in a developing country’s primary health care system. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:381–7.

National LQAS conference. Enhancing Evidence Based Planning at District Level: The LQAS Experience in Uganda Sheraton Hotel Kampala. 2006.

Hedt-Gauthier BL, Mitsunaga T, Hund L, Olives C, Pagano M. The effect of clustering on lot quality assurance sampling: a probabilistic model to calculate sample sizes for quality assessments. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2013;10:1.

Perez F, Ba H, Dastagire SG, Altmann. The role of community health workers in improving child health programmes in Mali. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9:28.

Biedron C, Pagano M, Hedt BL, Killian A, Ratcliffe, Mabunda S, Valadez JJ, et al. An assessment of Lot Quality Assurance Sampling to evaluate malaria outcome indicators: extending malaria indicator surveys. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:72–9.

Gigante J, Dell M, Sharkey A. “Getting Beyond”: How to Give Effective Feedback. Pediatrics. 2011;127:205. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3351.

Valadez JJ, Devkota B, Pradhan MM, Meherda P, Sonal GS, Dhariwal A, et al. Improving malaria treatment and prevention in India by aiding district managers to manage their programmes with local information: a trial assessing the impact of Lot Quality Assurance Sampling on programme outcomes. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(10):1226–36.

Oladele EA, Ormond L, Adeyemi O, Patrick D, Okoh F, Oresanya O, et al. Tracking the Quality of Care for Sick Children Using Lot Quality Assurance Sampling: Targeting Improvements of Health Services in Jigawa, Nigeria. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44319. doi:10.1371/joural.pone.0044319.

Gupte MD, Murthy BN, Mahmood K, Meeralakshmi S, Nagaraju B, Prabhakaran R. Application of lot quality assurance sampling for Leprosy elimination monitoring- examination of some critical factors. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:344–8. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh024.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the CHW Supervisors for the surveys. We thank the District Quality Improvement Team for support on the study. We are particularly grateful to all participating households from Luangwa District.

Funding

This project was funded by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (DDCF) through research grant number 2009060 (http://www.ddcf.org, RC). The funder had no role in the project design, data collection and data analysis of the results reported in this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data are part of large dataset that is being used for other purposes so it cannot be shared publicly. However, authors can be contacted for specific information that can be shared to individuals who are interested.

Authors’ contributions

MM supervised data collection, drafted and prepared the manuscript. JZ collected and verified the data from the field. ST revised the manuscript. PM performed the computational data analysis, WM revised the manuscript and RC revised, provided guidance. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent to publication

The Ministry of Health provided the authority to undertake and publish the research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by both the University of Zambia Biomedical Ethics and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Ethics Committees. The BHOMA study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov Identify NCT01942278. The ethical approval provided a waiver of individual written consent as this was a project to strengthen the routine health systems.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

BHOMA household monitoring tool. (PDF 90 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mwanza, M., Zulu, J., Topp, S.M. et al. Use of Lot quality assurance sampling surveys to evaluate community health worker performance in rural Zambia: a case of Luangwa district. BMC Health Serv Res 17, 279 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2229-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2229-9