Abstract

Background

Global curricular homogenization is purported to have a multitude of benefits. However, homogenization, as typically practiced has been found to promote largely Western ideals. The purpose of this study was to explore the issue of representation in the development of global oncology curricula.

Methods

This systematic review of global oncology curricula involved a comprehensive search strategy of eight databases from inception to December 2018. Where available, both controlled vocabulary terms and text words were used. Two investigators independently reviewed the publications for eligibility. Full global/core oncology curricular documents were included. Data analysis included exploration of representation across a number of axes of power including sex and geographic sector, consistent with a neocolonial approach.

Results

32,835 documents were identified in the search and 17 remained following application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Eleven of 17 papers were published from 2010 to 2018 and 13 curricula originated from Europe. The 17 curricula had 300 authors; 207 were male and most were from Europe (n = 190; 64%) or North America (n = 73; 24%). The most common curricular purposes were promoting quality patient care (n = 11), harmonization of training standards (n = 10), and facilitating physician mobility (n = 3). The methods for creation of these curricula were most commonly a committee or task force (n = 10). Over time there was an increase in the proportion of female authors and the number of countries represented in the authorship.

Conclusion

Existing global oncology curricula are heavily influenced by Western male authors and as a result may not incorporate relevant socio-cultural perspectives impacting care in diverse geographic settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In cancer education the profound mismatch between the training curricula for healthcare professionals and the needs of patients, families and the health-care system, such as team training to foster shared care models, is argued to fuel a healthcare crisis [1]. The sources of these mismatches are not fully understood, however, the potential overarching influence of Western medical priorities, in the form of neocolonialism, might be a contributing factor. An example of this includes the emphasis on the biomedical model of healthcare [2] at the exclusion of other ways of orienting to care and illness. This perpetuation of a Western biomedical model has also been identified by Fouad, in global oncology work [3]. This deserves further study as global, core or regional oncology curricula have been published by several international agencies [4,5,6,7,8] and improved understanding of how representation of non-Western values and approaches may inform the development of future global focused curricula or the use of existing curricula in diverse parts of the world.

The homogenization of curricula through the spread of Western ideals is purported to have a multitude of benefits [9] including the recognition of credentials globally and improving the quality of education and ultimately patient care. Medicine is an example of a ‘credential society’ and in situations where credentials are not universally recognized there is potential for brain waste [10]. Brain waste is a situation where migrant workers are not able to obtain employment commensurate to their educational qualifications [9] and can be related to brain drain (the migration of workers from low-middle income to high income countries). Brain waste is of significant concern to migrating physicians whereupon, with their arrival in high-inclome countries, they cannot practice as physicians [11]. In situations where there is great global need for health professional services, such as the growing health professional crisis in oncology, opportunities to minimize brain waste are encouraged [12]. Efforts, including standardization or training and global certification, which may ultimately reduce brain waste, may disproportionately benefit high-income countries. However, notwithstanding the purported benefits of standardizing health education training, the imposition of Western ideals across the world perpetuates neocolonial relationships, which may in turn lead to a mismatch between global priorities and local needs [13]. The increasing brain circulation experienced with the movement of cancer professionals to and from their home countries or regions, the mobility of patients seeking care and the introduction of international accrediting bodies [14] has resulted in the development of new global/core curricula. This creates an urgency to explore the influence of neocolonialism in global oncology curricula to inform future curricular development efforts that are sensitive to the needs of diverse regions of the world. A neocolonial approach allows for an in-depth analysis of socio-cultural and political imbalances perpetuated through the circulation of knowledge and educational tools. Table 1 outlines key concepts used in this paper. Our work is an effort to start such an analysis in the field of global oncology by exploring as a first step representation, a core tenet of neocolonial analysis, in the development of global oncology curricula.

The Best Evidence in Medical Education movement aims to promote a strong evidence base in a variety of topics on medical education [19] As a result, medical curricula are expected to be grounded and developed through educational research principles. Ad hoc teaching practices are questioned and those founded in educational research are given pre-eminence [20]. As the majority of the research in medical education is currently published in English language journals with origins in European and North American publishing houses [3] one must question if these Western priorities may dominate curriculum development and dissemination efforts. Arguably, in an effort to promote an evidence base in medical education, traditional beliefs and practices are overlooked while justifying the use of western pedagogical practices and priorities in non-western parts of the world [20] In other words, a challenge in establishing ‘core’ curricula in the current medical education landscape is the tension between meeting local needs and achieving international standards [20]. This can be particularly difficult for humanistic competencies such as professionalism [21]. The resistance to the inclusion of new concepts and content in curriculum redesign efforts is well recognized [20]. It is this tension between the need for reform and the desire to maintain some existing practices that make the exploration of representation in the development of global curricula an important area for study. We asked, is there a mechanism currently to engage diverse international players in the development of global oncology curricula [22]?

The purpose of this study was to explore the issue of representation in global oncology curricula by determining what global curricula exist for oncology, who has developed them, for what purpose and what methods were used in their development. Using an anti-colonial approach in our analysis we explored whether inequities in perspectives exist in global oncology curriculum development work.

Methods

Data collection

For this systematic review we incorporated an anti-colonial analytical approach with a comprehensive search strategy that included specifically looking for curricula from non-Western regions. To accomplish this, we included a comprehensive search of the published literature without any language restrictions. We hand searched the reference list of our included publications to ensure no other relevant publications were missed. In addition, we reviewed the websites of oncology organizations globally to look for global oncology curricula. We also included non-medical expert curricular content in our search to include curricula that may not focus on the dominant biomedical model.

We searched for global oncology curricula in the following databases from inception to December 2018; Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Ovid MEDLINE® Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, PsycINFO, all from the OvidSP platform; and CINAHL from EBSCOhost. There were no language or date restrictions because we wanted to ensure we included publications from all regions. Where available, both controlled vocabulary terms and text words were used to maximize our search results and account for global linguistic variations in the subject components for oncology curriculum/education, global and humanistic. We included a variety of terms to ensure we captured all manner of curricula that focused on oncology training including supportive care and non-medical expert knowledge domains and skills to ensure we captured diverse intersections of power. See Supplementary file 1.

In addition, a hand search of major international cancer organizations including The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [23], the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) [24], The European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) [25], the African Organization for Research and Training in Cancer (AORTIC) [26], The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR) [27], The Federation of Asian Organizations for Radiation Oncology (FARO) [28], The Asociacion Ibero Latinoamericana de Terapia Radiante Oncologica (ALATRO) [29], The Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology (CARO) [30], The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) [31] and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) [32] was conducted to ensure curricula which were not published were included to mitigate Western publication bias in this review.

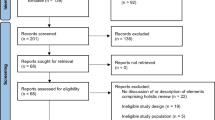

Duplicates were removed from the search by the information specialist. Two reviewers independently screened the curricula retrieved from the search. Consensus was reached on decisions to include or exclude potentially eligible curricula, with any disagreements resolved by adjudication by a third reviewer to make the final decision on eligibility for full-text review as necessary. For all eligible curricula identified the full text curricula were retrieved for detailed review, and independently screened by two reviewers. Any disagreements on inclusion of these curricula was resolved through adjudication by a third reviewer. A PRISMA flow chart was used to document the screening process.

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used for the systematic review. Curricula were included if their focus was on postgraduate medical education or residency level training in an oncology discipline (medical oncology, radiation oncology, and any surgical oncology specialty) their scope was global or multi-country/regional at a minimum. Regional was defined as the curricula focused on or was developed for use in two or more countries. For the purposes of this study a ‘global curriculum’ was conceptualized as a text, which intends to use a common vocabulary and shared philosophy, and which describes an outcome, including competency items, that are intended to be applicable across nations. The full curricula must be available either in the publication, as an online supplement or by contacting the authors or sponsoring institution. Papers were excluded if they did not include a curriculum (such as opinion papers, job descriptions, scopes of practice statements, program guidance documents, and position statements etc) because we focused on curricula as they are currently developed and in use. Curricula designed for undergraduate medical education, continuing medical education or non-medical professions were also excluded as they did not address the question of training for certification in an oncology specialty.

Data analysis

As mentioned above, the importance of representation in global health work has been stated by major healthcare agencies including the World Health Organization [33]. Anti-colonial theory has been previously used to explore power relationships in global health in medical education, including issues of representation [17, 34]. We were specifically interested in issues of representation in knowledge creation activities associated with the construction of global oncology curricula [2] and thus drew on anti-colonial theory to facilitate our analysis.

The curricular documents were analyzed and coded using NVivo version 11 [35]. Demographic details were extracted from the curricula including the medical specialties targeted by the curricula, the publication year, the number of authors, the authors’ sex, the authors medical specialty, the authors’ country, and data on translation from the primary language of publication to other languages. The purpose of the curricula and the methods used to develop the curricula were identified and coded. This analysis included application of an anti-colonial frame to determine representation across a number of axes of power including sex, language, profession and geographic sector. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the curricula.

Results

The search yielded 32,822 papers. An additional 13 papers were identified by hand searching relevant oncological organizations. This yielded a total of 32,835 papers. 9952 duplicates were identified and removed. The remaining 22,883 papers were then reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. 22,554 papers were excluded following this review. Full abstracts for the remaining 329 papers were obtained and reviewed. 281 papers were excluded leaving 48 papers that underwent full text review. Ultimately 17 of these papers met the inclusion criteria and formed the bases for analysis for this study. See Fig. 1.

What global curricula exist for oncology

Seventeen curricula were identified: 5 (29%) were from medical oncology, 5 (29%) were from radiation oncology, 5 (29%) were from surgical oncology, 1 (6%) from thoracic oncology and 1 (6%) from clinical oncology. Most of the curricula were published after 2000. 11 (65%) were published from 2010 to 2018. Table 2 summarizes the curricular details.

Who developed these curricula

The majority of these curricula, 13 (68%), originated from Europe. The 17 curricula had a total of 300 (mean 19; range 4–98) authors. The majority of the authors were male (n = 207, 69%). Most authors were from either Europe (n = 190; 64%) or North America (n = 73; 24%). Table 3 summarizes the author characteristics.

When the curricula were analyzed by the year of publication we identified a trend of increasing proportion of female authors from a mean of 17% in the oldest publications to a mean of 37% female authors in the more recently published curricula. In addition, the geographic distribution of authors represented in the publications increased from 1 country in the oldest publication to a mean of 9 countries represented in the most recent curricula. See Table 4.

What was the purpose for these curricula

The most common purpose for these curricula were promoting or improving the quality of patient care (n = 11), the harmonization of training standards (n = 10), and facilitating physician mobility across countries (n = 3).

What methods were used to develop the curricula

Eleven of the seventeen curricula describe the process used in their development of the curricula. The methods for creation of these curricula were most commonly a committee or task force (n = 10) and one was created using a modified Delphi process. All curricula were published in English. However, three provided official translation into 23, 8 and 5 languages respectively. Four curricula describe to what extent they have been externally endorsed. These data are summarized in Table 5.

Discussion

This theoretically framed systematic review of global oncology curricula has identified that the majority of these curricula originated from Western regions, were published in English for the primary document and are dominated by male authorship. We have demonstrated that there is an effort to include authors from varied global regions and women in the development of these global curricula in oncology as well as efforts to overcome the limitations of English publication through official translated documents. However, there remains a disproportional representation of Western authors participating in these consensus processes. This work sought to report, through an anti-colonial lens, a curricular review concept proposed by Bleakley et al. by reflecting on “what we are about when we design a programme of education” [17]. As stated by Bleakley et al. curricula, created through consensus agreement, are a human creation and therefore are influenced by those individuals’ interests and ideologies [17]. Using a European curricula as an example, a predominantly European representation on regional curricula for Europe is expected, it still remains important to explore the issue of regional representation given the increasing numbers of migrants and refugees around the world. Using the ESTRO Core curriculum as an example there was an increase in representation from 7 countries in 2004 to 32 countries in the 2011 version [7]. However, from our data we were not able to address the degree to which there was equity of contribution to the final curricular product by the various countries represented in the authorship, or what if any differences in opinion may have occurred during the deliberations. Addressing these details would be an important focus of future research best served by a qualitative approach.

The representation of female authors in the development of these curricula has increased over time. The proportion of women, while still under-represented compared to male authors, rose from 17% in the oldest curricula to a mean of 37% in the most recently published curricula. Women represent the majority of the global healthcare workforce, in Western and non-Western settings [49], as well as a growing proportion of the oncology workforce [50] and their underrepresentation in the development of global curricula is concerning. Ensuring representation of women, as they are delivering the majority of healthcare globally as well as representing a growing proportion of the oncology workforce, may be a factor in mitigating the perceived mismatch between curricula and desired competencies for clinical practice.

Although the training and credentialing of physicians remains largely a nation-bound activity currently, higher-education environments are simultaneously global, national and local [51]. Promoting physician mobility was one of the main purposes of these curricula identified in our study. Identifying this as a priority may reflect the decline of the nation-state in the face of a globalizing workforce [52]. The ability to move between nations promotes brain circulation and may reduce brain waste [9, 53]. This phenomenon is well recognized in the Canadian context where immigrant physicians were the least likely to be employed [53]. In oncology, where the profound lack of qualified oncologists in the face of a rapidly growing cancer population is resulting in serious gaps in cancer care, efforts to ensure all qualified physicians are seeing patients is laudable. However, caution is needed as there are many examples where mobility of credentials results in brain drain from low and middle income countries and may widen the gaps in access to care in areas that need it the most [9]. Models of training that address local needs, provide high standards of care and promote local and/or regional retention are desirable and have been achieved in areas such as psychiatry [54].

Much global health work is premised on study, research and practices that aim to improve health for all people [15] with an implicit assumption that care needs of cancer patients will be the same anywhere in the world. Eleven of the curricula in our analysis identified improving the quality of patient care as their purpose. Given the composition of the curricular committees that generate these materials, the effort may be perpetuating dominant Western discourses in medical care and training. A dominant discourse is “a particular language and a distinctive worldview in which some things are regarded as inherently more important or true than others” [55]. If we consider that the curricula identified in our work are mostly created by Western organizations, or certain dominant countries within a specific region, and engage to varying degrees’ authors, contributors and endorsements from other regions one questions to what degree dominant discourses of Western medical and educational priorities are imposed in regions across the globe. We must question how differing global interests and priorities are represented in these working groups; previous colonial structures can be reproduced in modern encounters [56]. We must continue to question how current curricula development practices, which largely rely on consensus work through committees may silence or otherwise poorly represent alternative or minority perspectives [57]. The discourse of the West improving patient care in the Global South is dominant in the literature. The non-Western perspectives are considered less knowledgeable about medical education and this may contribute to the disproportional representation of Western authors in global curricular efforts [56].

Our study has several limitations. One limitation of this work is the phenomenon of the marginalization of non-English language scholarship [51]. All of the curricula identified in this work were developed and initially published in English. Subsequently two were officially translated into five and eight languages respectively. The impact of the dominance of English-language in the global space of curriculum development requires further study as it is possible that the predominance of English language marginalizes other perspectives and does not incorporate regional or local practices [51]. This use of English to develop and disseminate the curricula for ‘quality’ training may also promote neocolonialism. Another limitation of our work, which utilized a systematic review strategy, is that of publication bias. The dominance of Western perspectives in the published literature is well known including in the field of global oncology [3]. The authors were conscious of the limitations and utilized hand searches of international groups in oncology as well as contacting members of these organizations including those that are not English speaking as their primary language. However, using the published literature as a focus for our work has allowed us to make explicit imbalances in representation that compromise sated efforts to produce curricula that are globally applicable. The methodology of a systematic review does not allow us to capture complex socio-political relationships at play in the development of global curricula. As the field struggles with questions of building capacity in oncology treatment around the world, future research should consider studying process and implementation issues using methods that are specifically designed to capture power issues. Another limitation is our categorization of different regions of the world as Western and non-Western. We acknowledge, while this facilitates the analysis, it is an oversimplification of the diversity of many countries which constitute these regions. Nevertheless, the socio-political history of medical fields has largely favoured Western high resource regions of the world and as our study shows, representing other perspectives and experiences required deliberate effort. In addition, we were not able to perform an intersectionality analysis to explore if the increase in female representation is dominated by a rise only in Western female participation [58]. This would be an important area for future work. Finally, we are not able to draw conclusions about the degree to which the representation bias is reflected in the content of the existing curricula, and hence the degree to which this content reflects the healthcare and health-system priorities in diverse geographic settings. We also were unable to report on the nature in which these curricula are actually implemented in local contexts and the degree of local customizations that occurs, including the incorporation of alternative, indigenous health approaches, to better address local health care needs is also not known. Further studies that employ a qualitative methodology would be better suited to addressing these critical considerations.

Conclusions

Using a critical, anticolonial lens we have reported the Western, male influence in the creation of global oncology curricula. We suggest, that as a result, these curricula may not incorporate relevant socio-cultural perspectives impacting care in diverse geographic settings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AORTIC:

-

The African Organization for Research and Training in Cancer

- ASCO:

-

The American Society of Clinical Oncology

- ASTRO:

-

American Society for Radiation Oncology

- CARO:

-

The Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica dataBASE

- ESMO:

-

The European Society of Medical Oncology

- ESTRO:

-

The European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology

- IEAE:

-

The International Atomic Energy Agency

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RANZCR:

-

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–58.

Hollenberg D, Muzzin L. Epistemological Challenges to Integrative Medicine: An anti-colonial perspective on the combination of complementary/alternative medicine with biomedicine. Health Sociol Rev. 2010;1(19):34-56.

Fouad T. Academic dependency: a postcolonial critique of global health collaborations in oncology. Med Anthropol Theory. 2018;5(2):127–41.

Burmeister J, Chen Z, Chetty I, Dieterich S, Doemer A, Dominello M, et al. The American Society for Radiation Oncology's 2015 Core Physics Curriculum for Radiation Oncology Residents. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95(4):1298–303.

Are C, Berman R, Wyld L, Cummings C, Lecoq C, Audisio RA. Global curriculum in surgical oncology. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(6):754–66.

Dittrich C, Kosty M, Jezdic S, Pyle D, Berardi R, Bergh J, et al. ESMO / ASCO recommendations for a global curriculum in medical oncology edition 2016. 2016.

Eriksen JG, Beavis AW, Coffey MA, Leer JWH, Magrini SM, Benstead K, et al. The updated ESTRO core curricula 2011 for clinicians, medical physicists and RTTs in radiotherapy/radiation oncology. Radiother Oncol. 2012;103(1):103–8.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). IAEA Syllabus for the Education and Training of Radiation Oncologists (2009); (Training Course Series No. 36). http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/TCS-36_web.pdf. Accessed 10 April 2019.

Spring J. Globalization of education: an introduction. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2014.

Brain VA, Revisited M. Globalisation. Soc Educ. 2006;4(1):7–24.

Lofters A, Slater M, Fumakia N, Thulien N. "Brain drain" and "brain waste": experiences of international medical graduates in Ontario. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:81–9.

Atun R, Jaffray DA, Barton MB, Bray F, Baumann M, Vikram B, et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(10):1153–86.

Martimianakis MA, Hafferty FW. The world as the new local clinic: a critical analysis of three discourses of global medical competency. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:31–8.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Royal College International (2020). http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/international-e. Accessed 22 Jan 2020.

Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1993–5.

PG A. Education and neocolonialism. In: Ashcroft B GG, Tiffin H, editor. The post-colonial Studies Reader. London: Routledge; 2004. p. 452–456.

Bleakley A, Brice J, Bligh J. Thinking the post-colonial in medical education. Med Educ. 2008;42(3):266–70.

Sharma M. Çan the patient speak?': postcolonialism and patient involvement in undergrduate and postgraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2018;52:471–9.

Best Evidence in Medical and Health Professional Education. The BEME Collaboration (2020) https://www.bemecollaboration.org/. Accessed 22 Jan 2020.

Sefton AJ. New approaches to medical education: an international perspective. Med Princ Pract. 2004;13(5):239–48.

Jha V, McLean M, Gibbs TJ, Sandars J. Medical professionalism across cultures: a challenge for medicine and medical education. Med Teach. 2015;37(1):74–80.

Sallie A, Marston KW, Jones JP. Flattening ontologies of globalization: The Nollywood case. Globalizations. 2007;4(1):45–63.

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). ASCO Annual Meeting (2020). https://www.asco.org/. Accessed 25 June 2017.

American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). ASTRO Targeting Cancer Care (2020). https://www.astro.org/home/. Accessed 25 June 2017.

European Society for Radiotherapy & Oncology (ESTRO). ESTRO (2020). http://estro.org/. Accessed 24 June 2017.

African Organization for Research & Training in Cancer (AORTIC). AORTIC (2001). http://www.aortic-africa.org. Accessed 1 July 2018.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR). (2020). http://www.ranzcr.com. Accessed 24 June 2017.

Federation of Asian Organizations for Radiation Oncology (FARO). What's new: FARO Meeting 2019 (2019). http://www.faroac.org/ Accessed 7 Jan 2020.

Asociación Ibero Latinoamericana de Terapia Radiante Oncológica (ALATRO). ALATRO (2019). http://www.alatro.org/. Accessed 7 Jan 2020.

Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology (CARO). (2016). http://www.caro-acro.ca/. Accessed 25 June 2017.

European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) (2020). http://www.esmo.org/. Accessed 24 June 2017.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). (2019). https://www.iaea.org/. Accessed 24 June 2017.

Keeling A. A new gender majority in the WHO leadership team announced or man bites dog in WHO. (2017). https://www.womeningh.org/single-post/2017/11/08/A-New-Gender-Majority-in-the-WHO-Leadership-Team-Announced-or-Man-Bites-Dog-in-WHO. Accessed 24 June 2017.

Whitehead CR. On gunboats and grand pianos: medical education exports and the long shadow of colonialism. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21(1):1–4.

NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2015. Available from: http://www.qrsinternational.com/nvivo.

Muss HB, Von Roenn J, Damon LE, Deangelis LM, Flaherty LE, Harari PM, et al. ACCO: ASCO core curriculum outline. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):2049–77.

Turner S, Seel M, Trotter T, Giuliani M, Benstead K, Eriksen JG, et al. Defining a leader role curriculum for radiation oncology: a global Delphi consensus study. Radiother Oncol. 2017;123(2):331–6.

Audisio RNP, Poston G, Wyld L. ESSO Core Curriculum 2013. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(S1):S1–S32.

Turner S MC, Longergan D, Holt T, Lehman M, James M, Lee M, Penniment M, Yuile P, Kok D, Lee A, Ng E, Allen A. Radiation oncology training program curriculum (2012). https://www.ranzcr.com/college/document-library/radiation-oncology-training-program-curriculum. Accessed 25 June 2017.

ESMO/ASCO Task Force on Global Curriculum in Medical Oncology, Hansen HH, Bajorin DF, Muss HB, Purkalne G, Schrijvers D, et al. Recommendations for a global core curriculum in medical oncology. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1603–12.

Naredi P, Leidenius M, Hocevar M, Roelofesen F, van de Velde C, Audisio RA. Recommended core curriculum for the specialist training in surgical oncology within Europe. Surg Oncol. 2008;17(4):271–5.

The Royal College of Radiologists. Specialty Training Curriculum for Clinical Oncology. London: The Faculty of Clinical Oncology; 2016.

Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board. Specialty Training Curriculum for Medical Oncology. London; 2017.

Are C1, Yanala U2, Malhotra G2, Hall B2, Smith L3,Wyld L4, Cummings C5, Lecoq C6, Audisio RA7, Berman RS8. Global Curriculum in Research Literacy for the Surgical Oncologist. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018 Mar;25(3):604–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-6277-5. Epub 2017 Dec 11.

Gamarra F, Noël J-L, Brunelli A, Dingemans A-MC, Felip E, Gaga M, et al. Thoracic oncology HERMES: European curriculum recommendations for training in thoracic oncology. Breathe. 2016;12(3):249.

Schweitzer RJ, Edwards MH, Lawrence W Jr, Mozden PJ, Scanlon EF, Leffall LD Jr. Training guidelines for surgical oncology. Cancer. 1981;48(10):2336–40.

Rauh SNO, Brandao M, Colomer R, Turhal S. European training requirements for the specialty of medical oncology. Brussels; 2017.

Baumann M, Leer J, Dahl O, De Neve W, Hunter R, Rampling R, et al. Updated European core curriculum for radiotherapists (radiation oncologists). Recommended curriculum for the specialist training of medical practitioners in radiotherapy (radiation oncology) within Europe. Radiother Oncol. 2004;70(2):107–13.

Langer A, Meleis A, Knaul FM, Atun R, Aran M, Arreola-Ornelas H, et al. Women and health: the key for sustainable development. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1165–210.

American Society of Clinical Oncology. The state of cancer care in America, 2017: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(4):e353–e94.

Marginson S. Global field and global imagining: Bourdieu and worldwide higher education. Br J Sociol Educ. 2008;29(3):303–15.

Scholte JA. Globalization: A critical introduction. 2nd ed: Macmillan International Higher Education: UK; 2005.

Goldberg MP. Discursive policy webs in a globalisation era: a discussion of access to professions and trades for immigrant professionals in Ontario, Canada. Glob Soc Educ. 2006;4(1):77–102.

Whitehead C, Wondimagegn D, Baheretibeb Y, Hodges B. The international partner as invited guest: beyond colonial and import-export models of medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(12):1760–3.

Brookfield S. The power of critical theory for adult learning and teaching. 1st ed. Columbus: Open University Press; 2005.

Hanson L, Cheng J. Production of the Global Health doctor: discourses on international medical electives. Engaged Scholar J. 2018;4(1):161–80.

Spivak GC. In other worlds: essays in cultural politics: New York; 2012.

Tsouroufli M, Rees CE, Monrouxe LV, Sundaram V. Gender, identities and intersectionality in medical education research. Med Educ. 2011;45(3):213–6.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This project was made possible with a Mapping the Landscape, Journeying Together grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation. Funding supported costs of data acquisition and salary support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (MG, RF, MB, JP, ED, TM, JF) contributed to study design and data analysis. MG, RF, MB and JP conducted data collection. All authors (MG, RF, MB, JP, ED, TM, JF) contributed to writing, reviewing and approving the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received a waiver from the UHN Research Ethics Board.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

MG has received funding from Elekta Inc., AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly not related to this work. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Ovid Medline search strategy: A Critical Review of Representation in the Development of Global Oncology Curricula and the Influence of Neocolonialism

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Giuliani, M., Frambach, J., Broadhurst, M. et al. A critical review of representation in the development of global oncology curricula and the influence of neocolonialism. BMC Med Educ 20, 93 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-1989-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-1989-9