Abstract

Background

With the increasing recognition that leadership skills can be acquired, there is a heightened focus on incorporating leadership training as a part of graduate medical education. However, there is considerable lack of agreement regarding how to facilitate acquisition of these skills to resident, chief resident, and fellow physicians.

Methods

Articles were identified through a search of Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, ERIC, PsycNet, Cochrane Systemic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from 1948 to 2019. Additional sources were identified through contacting authors and scanning references. We included articles that described and evaluated leadership training programs in the United States and Canada. Methodological quality was assessed via the MERSQI (Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument).

Results

Fifteen studies, which collectively included 639 residents, chief residents, and fellows, met the eligibility criteria. The format, content, and duration of these programs varied considerably. The majority focused on conflict management, interpersonal skills, and stress management. Twelve were prospective case series and three were retrospective. Seven used pre- and post-test surveys, while seven used course evaluations. Only three had follow-up evaluations after 6 months to 1 year. MERSQI scores ranged from 6 to 9.

Conclusions

Despite interest in incorporating structured leadership training into graduate medical education curricula, there is a lack of methodologically rigorous studies evaluating its effectiveness. High-quality well-designed studies, focusing particularly on the validity of content, internal structure, and relationship to other variables, are required in order to determine if these programs have a lasting effect on the acquisition of leadership skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The American healthcare system is in a state of tremendous flux, with the role of physicians and other healthcare providers rapidly changing to keep up with technological advances, financial restructuring, and the adoption of new societal and technological standards. Leadership training has been proposed as a means of managing these changes and ensuring that physicians are able to navigate their changing roles as health providers [1]. This follows the example of the business community, where leadership development is considered a high priority among managers.

Leadership is a term that is used to describe the ability of an individual to guide an organization or group of individuals [2]. In contrast to managers, leaders tend to exert authority through words and actions to convince followers towards a fulfillment of a vision, rather than through reward or punishment to induce control over subordinates. While considerable controversy exists over what styles and skills are necessary for effective leadership, this has become a burgeoning field of study. Sitkin and colleagues have identified six interrelated domains of leadership, namely personal, relational, contextual, inspirational, supportive, and responsible [3]. Each domain of leadership has an associated conceptual basis, group of behaviors, and set of skills. While an in-depth discussion of these domains and their application to medical education is beyond the scope of this article, acknowledgement of the importance of leadership and the heterogeneity of leadership styles is essential towards understandings the role of leadership development in graduate medical education.

With regards to medicine, it has been noted by several authors that there is a lack of leadership training for physicians in academic medical centers [4]. There has been a tendency to believe that leadership skills are acquired on the job and cannot be taught effectively, leaving a deficit of highly qualified physician leaders [5]. However, it is being increasingly recognized at least some leadership skills can be cultivated through formal and informal education, and that effective leaders cultivate their leadership capacity through diligent practice [6, 7]. Despite these calls for leadership training, the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has not yet articulated a specific position on leadership training. Currently, leadership skills constitute sub-competencies in two of the six competencies promoted by the Outcome Project of the ACGME, namely (1) professionalism and (2) interpersonal skills and communication skills [8]. New program requirements proposed by the ACGME have focused on the medical team, which is intimately linked to team leadership. Further, some of the members of the Council of Review Committee Residents Leadership Subcommittee of the ACGME have supported the need for leadership training, although they state that their opinions are not necessarily the official position of the ACGME [9].

There are scarce data about how leadership training programs are implemented in the framework of graduate medical education, i.e. residency and fellowship programs. Even less is known about the impact of these programs. Two systematic reviews have been performed regarding physician leadership training programs, but these did not specifically focus on resident and fellow physicians in North America, who operate in a very distinct environment and face unique challenges compared to physician executives, faculty members, and trainees in other geographic settings [10, 11]. In addition, a third systematic review focused on resident and fellow physicians in North America but did not assess the methodological rigor of included studies [12]. In order to document and characterize the impacts of these programs on leadership development, as well as provide direction for how to frame medical education interventions to study leadership development in graduate medical education, we have conducted a systematic review of literature.

Methods

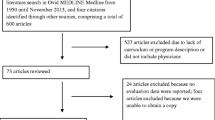

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was used to guide our literature search and report (Supplement). Figure 1 documents how we selected articles for inclusion in our analysis, and Table 1 documents the characteristics of the included studies.

Search strategy

Two authors (B.K. and M.L.S.) searched MEDLINE (from 1948 to January 31th, 2019), EMBASE (from 1988 to January 31th, 2019), CINAHL (from 1994 to January 31th, 2019), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (from 1996 to January 31th, 2019), Cochrane Systematic Reviews (from 1993 to June 30th, 2017), ERIC (from 1965 to January 31th, 2019) and PsycNet (1970 to January 31th, 2019), for potentially relevant studies. These searches were limited to articles written in English. A Boolean search strategy using a series of three terms was employed in order to obtain these articles. Search terms included (“medical education,” OR “residency,” OR “fellowship,” OR “medical training”) AND (“leadership” OR “management” OR “advocacy”) AND (“development” OR “skills” OR “training” OR “workshop” OR “session” OR “curriculum” OR “activities” OR “syllabus” OR “modules”).

Additionally, we supplemented this search by scanning the references of identified studies, as well as the related three systematic reviews [10,11,12]. In order to address publication bias, we also attempted to contact the authors of studies that were ultimately included in our review. The contact information of six authors was obtained, but only one had replied back with four articles, but none of these were new, previously unidentified studies.

Eligibility criteria

All qualitative and quantitative studies written in the English language that contained data regarding the implementation and evaluation of leadership training programs during graduate medical education were eligible. These graduate medical education programs consisted of residency and fellowship programs in either Canada or the United States. For our purposes, we included chief residents, who, depending on the training program, may be senior resident physicians or very recent graduates of residency programs. Due to the similarities in the structure of medical education training programs between Canada and the United States, we decided to include both countries.

We excluded studies that did not specifically deal with leadership training in graduate medical education, such as studies solely describing practice management or quality improvement. Similarly, we excluded studies that were not designed towards trainees in graduate medical education.

Study selection process

The two authors independently screened titles and abstracts compiled during the literature search. Full text of relevant articles was obtained based on the eligibility criteria noted above. Abstracts without concomitant full studies were excluded as they would be unlikely to provide enough detailed information for the systematic review. Conflicts were resolved by discussion and an apparatus was set up for a third author (M.S.) to resolve any discrepancies.

Data abstraction

The two authors jointly developed criteria for data abstraction. These included study design, physician characteristics, and outcomes. We discussed any studies that were subject to conflict, and calculated the kappa statistic. The MERSQI (Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument) criteria were used to appraise the methodological quality of included studies (Table 2).

Synthesis of included studies

A narrative review was drafted based on the included studies. While the original intent was to perform a meta-analysis, this could not be performed due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes and absence of an adequate sample size to test different variables.

Results

Literature search

Fifteen thousand one hundred fifty-nine citations were obtained through the literature search strategy, of which 46 articles were deemed potentially relevant. Thirty of these did not include data on either evaluation or implementation, resulting in 15 unique studies [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Among these, four were excluded since they were descriptive of new leadership curricula but lacked information on how effectiveness was assessed [28,29,30,31]. The kappa statistic was calculated and was 0.93 for the 15 included studies; the two authors disagreed about the inclusion of only one article which was adjudicated and it was determined that it should be included.

Study and population characteristics

Fifteen studies were altogether included in the analysis. Of the 15 unique studies identified, 12 were prospective case series and three were retrospective case series. Fourteen were quantitative in nature and one had a qualitative component. Surveys were used to determine the effect of the intervention in 12 of the studies, while another looked at outcomes in terms of awards, grants, and projects either won or executed by participants after completion. Among those evaluated by survey instruments, eight used self-assessment surveys and seven used course evaluations. Seven used pre- and post-test surveys while an eighth used a post-test and retrospective pre-test. Geographically, Fourteen studies were conducted in the United States and one was conducted in Canada. Two of these involved participants from multiple institutions [13, 15].

Altogether, there were 639 residents or fellows participating in the 15 studies. All participants were graduate medical education trainees, but these varied among different residency and fellowship training programs. Three were designed specifically for chief residents and three for senior residents, while the rest of the nine were open to residents of all different training years. Only one explicitly included fellow physicians in addition to resident physicians. Details regarding age and gender were not available for 13 of the 15 studies.

There was considerable variety in content, methods of instruction and the duration of intervention. Four studies did not enumerate the specific topics beyond development of “leadership skills.” The most common topics listed included teamwork, communication, and conflict resolution, which were seen in seven of the studies, followed by stress management in 4 studies. Ancillary topics in advocacy, personal finance, quality improvement, public health, and business management were also seen in several studies. A full list of topics covered is noted in Table 1.

The methods of instruction also varied: nine were workshops, four were didactic sessions, one was a series of small-group discussions, and one was an entire three-year residency program. Even among these, there was considerable heterogeneity in the length of time of each workshop/seminar, with some sessions as short as 30 min and others lasting for over 90 min. Additionally, the duration of training ranged considerably from a one-day workshop to a three-year residency program.

Quality assessment

Only two of the 15 studies included details on the age or gender of the participants, and so the representativeness of these studies compared to the general population of GME trainees is unclear. The 12 prospective case series did not detail specifically about how participants were selected, aside from being members of the residency or fellowship program. Similarly, no exclusion criteria were elaborated.

Self-reported questionnaires were utilized in 14 of the 15 of the studies. However, only one was noted to be validated by authors. Also, none described blinding of outcomes assessment. One study reported follow-up after 6 months; two additional studies reported follow-up after 12 months. The remaining 12 did not have follow-up. One study looked at the outcomes in terms of awards and grants 6 years after graduation of the first set of cohorts.

MERSQI scores were calculated for each of the included studies, and varied from 6 to 9 out of a possible maximal score of 18 (Table 2).

Impact of leadership programs

Among the seven studies that used pre- and post- self-assessment surveys, all showed improvement in the perceptions and attitudes of knowledge and leadership skills, although measured in different ways. In the six surveys evaluating the programs themselves, there was broad satisfaction at the quality and content of the program.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to characterize and appraise leadership development programs specifically among graduate medical education trainees. Of note, one prior systematic review had appraised the strength of conclusions using the Best Evidence in Medical Education (BEME) Index, but did not appraise the methodology, framework, and results in total. To do so, we employed the MERSQI. The MERSQI is a validated and widely used instrument to assess quality of educational interventions, and, among the most commonly used instruments (BEME, MERSQI, modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [m-NOS]), it is most strongly associated with study quality, as assessed by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [32]. By using the MERSQI to more critically inspect these studies, our analysis informs educators about how to build upon what has been previously published to better structure leadership development programs in graduate medical education training programs.

The biggest limitation in the design of these studies is the lack of validity (Internal structure, content, and relationship to other variables). Only one article (Lee, Tse, and Naguwa [18]) documented efforts to ensure that there was validity in the internal structure of their intervention. None sought to validate content and relationship to other variables. We strongly recommend that future studies critically examine and report the steps that they take to ensure validity. Admittedly, this is difficult given the absence of a single definition of leadership and the tendency for leadership to be viewed as a situationally- and contextually-dependent competency [3,4,5]. However, it should not deter investigators in exploring and analyzing how the variables being measured may link to the concept of leadership.

Likewise, future studies need to examine outcomes on patient/healthcare and behaviors. Only one of the 15 examined knowledge or skills (Whitman [13]) while the others studied satisfaction, attitudes, and perceptions as outcomes. Because leadership is so intrinsically tied to behavioral patterns, evaluation of these sorts of outcomes is essential [1, 2]. Likewise, leadership is consistently mentioned in the articles included in our analysis as potentially transformative for healthcare, yet the impacts of these interventions on such outcomes are not measured or documented. This is an understandable limitation given the practical challenges of designing medical education studies but it is difficult to interpret the significance of these studies without data regarding more meaningful outcomes that are more closely tied to leadership.

Of course, our analysis has some important limitations. First, because leadership encompasses several overlapping concepts, the foci of these studies were slightly different. Some articles did not break down what types of leadership skills were emphasized in these training programs, while others provided significantly more detail. This variability in content and focus underline the importance of looking critically at leadership as a set of overlapping competencies. Moreover, it reinforces the need to scrutinize study design and methodology of prior published studies, over specific results, since it is unclear how much overlap there is in content between the curricula of the 15 included studies.

Second, the outcomes reported were largely self-reported through non-validated questionnaires. Except for Kuo’s report of the establishment of a three-year residency program, all of the included studies used either pre- and post-test knowledge-based assessments, or self-assessments. Six of the studies that evaluated the course content and composition demonstrated that participants were satisfied, according to the authors’ conclusions. Additionally, 6 studies demonstrated there was a positive impact on their own perception that they had learned about leadership skills. While these are helpful in determining what was learned and how learners viewed their experiences, it does not necessarily provide information about how leadership training impacts behaviors or institutional culture. The absence of follow-up beyond the initial training course in all but three studies also makes it difficult to determine what lasting impact these training programs had on participants.

Thirdly, inclusion and exclusion criteria were not clearly elucidated in the included studies. In the absence of this information, it is difficult to ascertain selection bias or drop-out between training sessions. Similarly, demographic information regarding age and gender were missing in all but one study. These findings preclude generalization of any particular conclusion about leadership training in graduate medical education.

Our systematic review does have certain methodological shortcomings. We limited our search to articles focusing on leadership, but due to the ambiguities regarding the precise definition of leadership, we may have missed articles related to “team leaders,” “managers,” “self-management” or other topics within the realms of leadership training. It is therefore vital to establish clearer definitions of leadership in the context of healthcare and to articulate what competencies define physician leadership. Using clearer definitions of leadership may facilitate investigators to better describe their efforts to uphold the validity of contents, internal structure, and relationship to other variables.

Strengths of our systematic review include the use of multiple databases and the solicitation of other references by both searching the reference lists and by attempting to contact authors of the published material. The methodological rigor of the review was upheld through strict adherence to the PRISMA statement, and each study was evaluated by the MERSQI, a validated instrument to appraise the methodological quality of studies.

Conclusion

This systematic analysis has identified a significant absence in the publication of rigorously designed and evaluated leadership training programs. There is particularly a lack of studies that describe the validity of content, relationship to other variables, and internal structure. What has been published suggests that leadership training is a worthwhile endeavor, and that participants do learn more about leadership and are favorably disposed to workshops and seminars. We recommend that further high-quality research be undertaken in order to better understand how leadership skills can best be imparted for trainees in graduate medical education, and how formal training programs influence more long-term and objective measures of leadership and management.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ACMGE:

-

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

- BEME:

-

Best Evidence in Medical Education

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica Database

- MERSQI:

-

Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument

- m-NOS:

-

modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

References

Mafe C, Menyah E, Nkere M. A proposal for health care management and leadership education within the UK undergraduate medical curriculum. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:87–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S96781.

Rosenman ED, Branzetti JB, Fernandez R, et al. Assessing team leadership in emergency medicine: the milestones and beyond. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):332–40.

Sitkin SB, Lind EA, Siang S. The six domains of leadership. Lead Lead. 2009;2006(S1):27–33.

LeTourneau B, Curry W. In search of physician leadership. Chicago: Health Administration Press; 1998.

Mipos D. Are all physicians leaders? The opinions of Permanente physician–leaders. Permanente J. 2002;6:55–6.

Berwick DM, Nolan TW. Physicians as leaders in improving health care: a new series in annals of internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:289–92.

Fairchild DG, Benjamin EM, Gifford DR, Huot SJ. Physician leadership: enhancing the career development of academic physician administrators and leaders. Acad Med. 2004;79:214–8.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/home/home.asp. Accessed 25 July 2016.

Jardine D, Correa R, Schultz H, et al. The need for a leadership curriculum for residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):307–9.

Straus SE, Soobiah C, Levinson W. The impact of leadership training programs on physicians in academic medical centers: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(5):710–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828af493.

Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, et al. Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):656–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1.

Sadowski B, Cantrell S, Barelski A, et al. Leadership training in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(2):134–48.

Whitman N. A management skills workshop for chief residents. J Med Educ. 1988;63(6):442–6.

Doughty RA, Williams PD, Seashore CN. Chief resident training. Developing leadership skills for future medical leaders. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145(6):639–42.

Mygdal WK, Monteiro M, Hitchcock M, et al. Outcomes of the first family practice chief resident leadership conference. Fam Med. 1991;23(4):308–10.

Evans DV, Egnew TR. Outdoor-based leadership training and group development of family practice interns. Fam Med. 1997;29(7):471–6.

Crites GE, Schuster RJ. A preliminary report of an educational intervention in practice management. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4:15.

Lee MT, Tse AM, Naguwa GS. Building leadership skills in paediatric residents. Med Educ. 2004;38(5):559–60.

Stoller JK, Rose M, Lee R, et al. Teambuilding and leadership training in an internal medicine residency training program. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):692–7.

Hemer PR, Karon BS, Hernandez JS, et al. Leadership and management training for residents and fellows: a curriculum for future medical directors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(4):610–4.

Stergiopoulos V, Maggi J, Sockalingam S. Teaching the physician-manager role to psychiatric residents: development and implementation of a pilot curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(2):125–30.

Pettit JE, Dahdaleh NS, Albert GW, et al. Neurosurgery resident leadership development: an innovative approach. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(2):546–50 discussion 550.

Kuo AK, Thyne SM, Chen HC, et al. An innovative residency program designed to develop leaders to improve the health of children. Acad Med. 2010;85(10):1603–8.

Brandon CJ, Mullan PB. Teaching medical management and operations engineering for systems-based practice to radiology residents. Acad Radiol. 2013;20(3):345–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2012.09.025.

Cole DC, Giordano CR, Vasilopoulos T, et al. Resident physicians improve nontechnical skills when on operating room management and leadership rotation. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(1):300–7.

Itri JN, Yacob S, Mithqal A. Teaching Communication Skills to Radiology Residents. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2017;46(5):377–81.

Hill DA, Jimenez JC, Cohn SM, et al. How to be a leader: a course for residents. Cureus. 2018;10(7):e3067.

Ackerly DC, Sangvai DG, Udayakumar K, et al. Training the next generation of physician-executives: an innovative residency pathway in management and leadership. Acad Med. 2011;86(5):575–9.

Babitch LA. Teaching practice management skills to pediatric residents. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45(9):846–9.

Awad SS, Hayley B, Fagan SP, et al. The impact of a novel resident leadership training curriculum. Am J Surg. 2004;188(5):481–4.

Wipf JE, Pinsky LE, Burke W. Turning interns into senior residents: preparing residents for their teaching and leadership roles. Acad Med. 1995 Jul;70(7):591–6.

Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S. Method and reporting quality in health professions education research: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45(3):227–38.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jeffrey Pettit, PhD MA and Hanna Mawad, MD.

Funding

This study was funded through the Arnold P. Gold Research Institute’s “Mapping the Landscape, Journeying Together” Grant. This funding body was not involved in the design of the study, in data-collection, −analysis, and -interpretation and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BK: literature review concept design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript. MLS: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript. MS: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MS is an Associate Editor of BMC Medical Education.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Appendix 1: PRISMA Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, B., Swee, M.L. & Suneja, M. Leadership training programs in graduate medical education: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ 20, 175 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02089-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02089-2