Abstract

Background

Recent studies have gone to great lengths to differentiate mentoring from teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision in efforts to better understand mentoring processes. This review seeks to evaluate the notion that teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision may in fact all be part of the mentoring process. To evaluate this theory, this review scrutinizes current literature on teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision to evaluate their commonalities with prevailing concepts of novice mentoring.

Methods

A three staged approach is adopted to evaluate this premise. Stage one involves four systematic reviews on one-to-one learning interactions in teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision within Internal Medicine, published between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2018. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach to thematic analysis was used to identify key elements within these approaches and facilitate comparisons between them.

Stage two provides an updated view of one-to-one mentoring between a senior physician and a medical student or junior doctor to contextualise the discussion.

Stage three infuses mentoring into the findings delineated in stage one.

Results

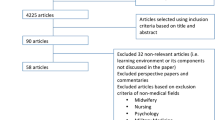

Seventeen thousand four hundred ninety-nine citations were reviewed, 235 full-text articles were reviewed, and 104 articles were thematically analysed. Four themes were identified – characteristics, processes, nature of relationship, and problems faced in each of the four educational roles.

Conclusions

Role modelling, teaching and tutoring, coaching and supervision lie within a mentoring spectrum of increasingly structured interactions, assisted by assessments, feedback and personalised support that culminate with a mentoring approach. Still requiring validation, these findings necessitate a reconceptualization of mentoring and changes to mentor training programs and how mentoring is assessed and supported.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mentoring nurtures professional and personal development [1], improves learning and clinical competency and enhances career satisfaction amongst mentees and mentors [2, 3]. These successes are largely reliant upon the mentor’s ability to nurture personalized mentoring relationships and steer the mentoring process [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. To do so, mentors adopt many supportive and educational roles [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. These include being a supervisor “focused upon professional development of the student”, a coach facilitating learner development through use of “deliberate practice strategies”, a role model “setting out to create a positive example of good practice”, an advisor “helping with scheduling, logistics and applications” and a sponsor “influencing promotion and advancement” [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. This has fuelled the notion that teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision lie within the scope of a mentoring role and dismissed long-held beliefs that conflation between these practices and mentoring was a significant source of confusion in conceptualizing mentoring. To better understand this perspective, a clear understanding of teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision is warranted. This requires distancing these practices from prevailing accounts of mentoring that is often conflated with these supportive and educational roles [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Here mentoring is defined as a ‘dynamic, context dependent, goal sensitive, mutually beneficial relationship between an experienced clinician and junior clinicians and or undergraduates that is focused upon advancing the development of the mentee’ [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

The need for this study

The implications of this theory would necessitate a review of how mentoring is conceived and have wide-ranging effects upon the understanding, structuring, oversight and support of mentoring approaches, curricula and mentor training programs [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Methods

To evaluate the notion that teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision may be a part of an overarching concept of mentoring, this study was made up of three stages. Stage 1 consists of systematic reviews of teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision carried out to provide better understanding of these processes. In acknowledgement of mentoring’s, coaching’s and supervision’s context-dependent, approach-specific nature, studies were confined to educational accounts that involve one-to-one interactions between tutor and learner. The term tutor was used to encapsulate mentor, supervisor, teacher, role model and coach.

Stage 2 drew upon prevailing descriptions of novice mentoring, the dominant form of mentoring, given that mentoring’s context dependent nature prevents conflation of different forms of mentoring [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Stage 3 sought to determine similarities between teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision and mentoring.

To carry out the systematic reviews, Stage 1 adopted Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach to thematic analysis to identify key themes within teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision in medical education [17].

Stage 2 drew upon recent accounts of novice mentoring. Focus was maintained on novice mentoring which is the dominant form of mentoring in medical education and to prevent it from being conflated with other distinct forms of mentoring such as peer, group and e-mentoring [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Stage 3 sought comparisons being made between novice mentoring and teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision to determine the overlap between each of these approaches.

Stage 1: thematic analysis of teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision

Methodology

A systematic review was proposed to explore the size and scope of available literature on assessing the impact of medical ethics education in published peer-reviewed literature [18,19,20,21,22]. This allowed for systematic extraction and synthesis of actionable and applicable information [23] whilst summarizing available literature [24, 25] across a wide-range of pedagogies, assessment contents and practice settings [26,27,28,29,30].

Levac et al. (2010) [31]‘s and Arksey and O’Malley (2005) [18]‘s framework for systematic review was used to map “the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available” [21] and “produce a profile of the existing literature in a topic area, creating a rich database of literature that can serve as a foundation” to inform practice and guide further research [19, 32, 33].

Guided by PRISMA-P 2015 checklist [24], Levac et al. (2010) [31]‘s and Arksey and O’Malley (2005) [18]‘s framework, a 6-stage systematic review protocol was developed for this study [18,19,20,21,22, 31].

Stage a: identifying the research question

Guided by two librarians from the medical libraries at Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at National University Singapore and the National Cancer Centre Singapore and educational experts and clinicians from the Singapore General Hospital, the Division of Cancer Education at the National Cancer Centre Singapore and the Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute at the University of Liverpool (henceforth the advisory team), the 14-person research team (YR, JY, AH, KT, KP, NQ, RP, BT, AC, YP, RK, DT, SM, and LK) discussed prevailing concepts and practice surrounding issues, and practices surrounding teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision and identified the primary research question to be: ‘what is known of teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision in Internal Medicine?’. The secondary questions were “what are the key elements of teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision in Internal Medicine?’. These questions were designed on the population, concept and context elements of the inclusion and exclusion criteria [34, 35], using a PICOS format (Table 1).

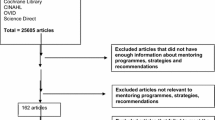

Guided by the advisory team, the 14-person research team worked in teams of threes under the supervision of the senior researchers (LK, SM, DT, and RK) and supported by near peer mentors (YP and KT) to carry out independent searches of accounts of role modelling, teaching, tutoring, coaching and supervision published in the PubMed, Scopus, ERIC and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The searches were carried out between the 12th September 2017 and 18th October 2017. The respective search strategies are found in the PRISMA in Fig. 1. In keeping with Pham et al. (2014) [33]‘s approach of ensuring a viable and sustainable research process, articles published in English or had English translations published between 1st January 2000 to 31st December 2015 were included in the initial search.

With all searches reviewed by the senior reviewers, the review process was extended, and additional searches were performed between 12th May 2019 and 24th April 2019 to review newly published literature from 1st January 2016 to 31st December 2018 for each of the learning approaches.

Focus was on accounts of role modelling, tutoring, teaching, coaching and supervision that clearly described one-on-one interactions between a clinician and a learner in Internal Medicine. Accounts of teaching, tutoring and role modelling that did not clearly state one-on-one interactions were excluded as it did not facilitate comparisons with mentoring, supervision and coaching. Accounts of teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision in clinical specialities not traditionally associated with Internal Medicine as defined by the World Health Organization’s classification of healthcare workers, were also excluded to further focus this review [36].

Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach to thematic analysis [17] was used to circumnavigate the wide-range of research methodologies that made statistical pooling and analysis difficult [17] in the papers reviewed. The narrative produced was guided by the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide [37] and the STORIES (Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement [38].

Stage B: identifying relevant studies

Guided by the advisory team, the research team developed individual search strategies for teaching, tutoring, role modelling, coaching and supervision and selected PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and ERIC databases for review. In keeping with Pham et al. (2014) [33]‘s approach of ensuring a viable and sustainable research process, the research team confined the searches to articles published between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2018 to account for prevailing manpower and time constraints faced by the team.

Stage C: selecting studies to be included in the review

After the independent searches of the databases were combined employing the ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach and a final list of article to be reviewed was determined, the 7-members of the research team (YR, JY, AH, KP, NQ, RP, BT) guided by the senior reviewers (SM, RK, DT and LK) and near peer mentors (KT and YP) independently screened the title and abstracts.

A consensus based approach employing the ‘negotiated consensual validation’ approach was reached on the final list of papers to be included for thematic analysis [39].

The PRISMA charts are attached below (Fig. 1).

Stage D: data characterization and analysis

In the absence of a priori framework and a clear definition of role modelling, teaching and tutoring, coaching and supervision, Braun and Clarke’s (2006) [17] approach to thematic analysis was adopted to identify consistencies across these approaches [2, 14, 15, 17, 40,41,42,43,44].

Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach was used to create codes from the ‘surface’ meaning of the data. Semantic themes were identified from ‘detail rich’ codes focused upon the various aspects of the role modelling, teaching, tutoring, coaching and supervisory process [17]. Each of the 10 coded scripts from role modelling, teaching and tutoring, coaching and supervision were reviewed by the senior reviewers. The research team discussed and agreed upon a common coding framework and codebook using Sambunjak et al. (2010)‘s “negotiated consensual validation” approach [45]. Working in teams of three, overseen by the senior reviewers (SM, RK, DT, and LK) and peer mentors (KT and YP), the reviewers carried out independent thematic analyses of all articles in each of the four topics using the codebook, with new codes discussed online and at face-to-face at reviewers’ meetings [17, 46,47,48,49].

Stage E: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

From the 18,938 articles reviewed, 34 articles on role modelling, 9 articles on teaching and tutoring, 43 articles on coaching and 18 articles on supervision were identified. The four themes identified include characteristics, processes, nature of relationship, and problems of the four educational roles.

The narrative produced was guided by the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide [37] and the STORIES (Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement [50].

Results

Characteristics of each of the four educational roles

Thematic analysis of the prevailing descriptions of role modelling, teaching, tutoring, coaching and supervision were carried out. Their characteristics and descriptions are highlighted in the table below (Table 2).

Educational processes

Role modelling is often a ‘one off’ unstructured experience that neither the learner nor the role model has prepared for [100]. Role modelling may be unconsciously carried out and may be either an exemplary action or one that ought not to be repeated [55, 57, 59, 62]. Given the unplanned nature of role modelling, it may even breach standards of practice [55, 57, 59, 62]. Role modelling may not have a longitudinal component and is often not appraised [55, 57, 59, 62], subject to feedback or reflection [60, 63, 100,101,102].

The learning processes in teaching and tutoring, coaching and supervision are interactive [64,65,66, 74,75,76,77, 79, 81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91, 93,94,95,96,97,98], context-specific, goal-sensitive and dynamic [63, 75, 82, 84,85,86, 92] process that are guided by the objectives of the clinical training program [66, 70, 71, 92, 93, 99] and supported and overseen by a host organization [67, 68, 73, 76, 77, 82, 83, 92].

Teaching and tutoring need not be matched though having learners and tutors with complementary abilities, motivations, personalities, and values for coaching and supervision is helpful. Teaching and tutoring, coaching and supervision is influenced by individual learning goals [75, 82, 84,85,86], relationships [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81], program structure [67, 68], assessments [66, 70, 71], and environment [64]. All teaching and tutoring, coaching and supervision programs are structured, planned, and often have longitudinal component which are horizontally and vertically integrated [90, 103, 104]. The programs usually include feedback, reflection and an evaluative process [90, 103, 104].

The distinctive aspects of each learning processes are highlighted in Fig. 2.

Nature of relationship

Role Modelling

Role modelling is unpredictable and involves varying levels of interaction and communication [100]. Some interactions are purposive; built through sharing of professional and personal experiences and socializing [60, 63, 101, 102] whilst others are entirely opportunistic.

A lack of structure however may result in negative role modelling [55, 57, 59, 62]. Negative role modelling [55, 57, 59, 62] may dissuade students from particular career choices [57], cause trainees to become cynical about academic life [62], discourage reflective practice skills [55] and undermine professional and patient-centered behaviour [63].

Teaching and tutoring

Structured programs [66] that include experiential learning [65,66,67,68,69,70,71], discussions [70, 71], or guided reflections [65, 66] formed the basis for teacher-student interactions [65, 70]. Given the variability of these interactions [68, 69, 71, 105], teacher-student relationships tend to be superficial [65, 66]. However, supportive and approachable teachers [65,66,67, 106], who are willing to commit and provide student-centric teachings [65, 66, 70, 105], are able to develop more successful learning relationships and achieve greater goals [69, 70, 106].

Coaching

The relationship between the coach and trainee is focused upon learning a specific skill [72]. The complexity of the skill determines the duration of the relationship [72].

Coaching begins with the demonstration of the skills in a planned role modelling process, which tapers over time as goals were achieved and as trainees develop their ability to self-monitor and sustain their training [72].

It is debatable as to whether coaching provides psychological and emotional support [74, 80, 84]. Some commentators suggest that coaching relationships are transactional and focused upon professional improvement whilst others suggest the presence of evaluations within coaching interactions necessitate a trusting [74, 80, 84] and safe environment [73, 90, 91].

Supervision

The supervisory relationships are hierarchical [92]. With the trainee dependent on the supervisor for academic progression and career advancement [92], trusting relationships between supervisor and trainee are less likely [92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99].

A comparison of the nature of relationships across various educational roles are found in Appendix 1 in Table 4.

Problems faced in the four educational roles

Each of these educational approaches face common problems. Many revolve around insufficient training, poor program structure, inadequate learning resources and inaccurate program evaluation and learning assessment [55, 80, 93, 95, 96, 100, 107,108,109,110,111].

Role modelling faces limited time for teaching [55, 100, 107,108,109] and bedside tutorials [110] whilst coaching faces inadequate financial, administrative and assessment support that are not conducive of nurturing organizational culture to ensure protected time and recognition for coaches [80, 111].

Supervision faces organizational issues that include a lack of consistent level of support and training [93], resource limitation and competing tensions between service and education demands [95, 96]. A detailed account of these challenges is found in Appendix 2 in Table 5.

Discussion

Drawing the findings together

Based on the data from the four systematic reviews, it is possible to proffer a clearer understanding of each of the approaches.

Role Modelling

Positive role modelling can be defined as “a process where a trainer consciously or unconsciously demonstrates positive or negative behaviours, actions or attitudes. The learner observes, weighs up and reflects upon these characteristics, skills and or behaviours upon their own practice/attitude/behaviour and emulates, experiments, and assimilates it into his/her own personal/professional identity. Positive role modelling is more impactful when it occurs in a trusting, professional relationship.” [51,52,53,54,55, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64, 100, 102, 109, 112,113,114,115]

Teaching and tutoring

Teaching and tutoring is “a professional goal-specific [66], task-oriented [66], standardized [67, 68], and structured learning process [66, 69] on clinical knowledge and skills [65,66,67,68,69,70,71], driven by clinical competency and performance outcomes [69, 70, 106]. The professional [65, 66, 69,70,71, 105, 106], tutor-, and student-dependent [65, 66] tutor-learner relationship requires protected time [65,66,67, 70] to develop in a safe and productive learning environment [69], supported by the host organization [67], for effective teaching [65, 67, 69,70,71, 106] and feedback [66, 67, 70, 71, 105] processes.”

Coaching

Coaching can be defined as a “longitudinal professional relationship between an expert coach and a trainee focused upon mastery of a clearly defined, measurable and achievable skill that is that the trainee or training organization feels the trainee can improve upon. The relationship is built upon professional trust in a ‘safe environment’ that facilitates practice of the skill. The coach evaluates the performance, needs and abilities of the trainee, role models skills, encourages learning, provides specific individualized feedback and devises a plan to achieve the goals. The trainee is accountable for their training and responsible for self-monitoring.” [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86, 88,89,90,91]

Supervision

Supervision is an “individualized, focused, goal-specific, time-limited and context-sensitive clinical training process by a senior clinician aimed at assessing and improving particular gaps and weaknesses in the clinical care and patient safety by trainees by providing them with oversight, guidance and feedback and holding trainees up and accountable to established clinical standards and codes of practice. This process will utilize coaching and role modelling to meet its goals [92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99].

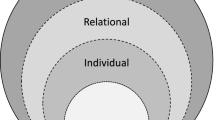

Comparing the findings of the four systematic reviews, there are a number of key insights and similarities that may be discerned. These commonalities lay the foundation for a collective perspective of the four educational approaches. These features are shown in Table 3 and the characteristics of each approach is shown in Fig. 3.

The data would suggest that the more relevant aspects of role modelling appears to be contained within teaching and tutoring, which in turn appears to be subsumed by coaching. Supervision appears to contain features of role modelling, teaching and tutoring, and coaching.

Viewed figuratively as concentric rings, role modelling would be at the centre of the rings, enclosed by teaching and tutoring, then coaching and finally supervision as the outer most ring.

Stage 2 mapping mentoring practice

To determine mentoring’s relationship with the concentric rings featured in Fig. 3, Stage 2 will provide a summary of prevailing concepts of mentoring drawn from two recent systematic scoping reviews of novice mentoring and a recent study of mentoring experiences within a novice mentoring program.

Sng et al. (2017) [2]‘s and Tan et al. (2018) [12]‘s systematic scoping reviews highlight a number of key aspects of mentoring

- 1.

Mentoring can be defined as ‘dynamic, context dependent, goal sensitive, mutually beneficial relationship between an experienced clinician and junior clinicians or undergraduates that is focused upon advancing the development of the mentee’.

- 2.

Mentoring possesses adopt an evolving, adaptive, goal-specific, context-sensitive, and mentee-, mentor-, relationship-, and host organization-dependent nature (mentoring’s nature) that prevents conflation with other forms of mentoring.

- 3.

Novice mentoring’s success lies with its nurturing of personalized relationships between the mentee and mentor

- 4.

To develop personalized mentoring relationships, there must be balance between individualization of mentoring relationships that includes catering to the mentee’s needs, abilities, goals and situation and ensuring a consistent mentoring approach that is both compliant to prevailing codes of conduct and sufficiently structured to allow effective, timely, appropriate, personalized, specific, holistic, longitudinal and accessible evaluations and support for the mentee, mentoring and the mentoring relationship.

Evidencing these findings and forwarding new insights of novice mentoring, Krishna et al. (2019) [3]‘s study of mentoring experiences in a novice mentoring program also unearthed new aspects to mentoring. These include

- 1.

mentoring’s competency-based stages of development that requires mentees to achieve basic competencies at each stage of the mentoring process before progressing to the next stage.

- 2.

progress through the various stages of mentoring requires effective communication, timely and appropriate assessments and support appropriate balancing between consistency and structure.

- 3.

oversight and support of the mentoring process depends upon the host organization and well-trained and supported mentors.

Stage 3 mentoring Spectrum

Mentoring’s use of personalized holistic and longitudinal support throughout the mentoring process would require mentees to be taught, and provided with guidance as they apply their knowledge and skills, be assessed and provided with feedback and then re-evaluated before progressing to the next stage of the mentoring process. At each stage of the mentoring process which Krishna et al. (2019) [3] describe as “‘circumscribed sequential projects’ with ‘specific goals and competency requirements’” , it is likely that mentors will employ role modelling, teaching and tutoring, coaching and supervision to support the mentee and the evolving mentoring relationship. This would see mentoring encompassing supervision’s role and occupying the outer most ring in Fig. 4.

This suggests that role modelling, teaching, tutoring, coaching and supervision lie within a mentoring spectrum (Fig. 4). The mentoring spectrum describes a range of educational practices contained under the aegis of mentoring beginning with role modelling on the left side of the spectrum and mentoring on the right. Beginning with role modelling, there is progressively complex interactions culminating with personalized attention in role modelling behaviours, attitudes and practices, teaching new skills and knowledge, coaching individual learner’s on different aspects of the skills they need, appraising their progress and providing feedback as they are supervised to complete their immediate goals within the project. Separating supervision from the more complex relationships seen in mentoring is the provision of personalized, timely, holistic and longitudinal support and the adaptation of the mentoring approach to accommodate the mentee’s needs, goals, circumstance and abilities.

Other features that evidence the notion of a mentoring spectrum include

- 1.

Motivation of learners

All educational approaches are reliant upon the learner’s ability to observe, discern gaps in their ability, learn, reflect, weigh up considerations, be open to feedback and be accountable for their own learning. However, the approaches rely on increasing learner motivation moving from left to right of the mentoring spectrum.

- 2.

Learning Relationship

Moving from left to right along the mentoring spectrum also highlights increasing planning and structuring of the mentoring process. Improved structuring of educational interactions better supports learning relationships and nurtures more holistic and personalised educational relationships. Better learning relationships also facilitate better outcomes.

Learning relationships also become more interactive moving from left to right in the mentoring spectrum. In role modelling, learners may not have an educational relationship with the tutor whilst learning relationships in mentoring are dynamic and enduring [2, 92, 116,117,118,119].

- 3.

Nurturing learning environment

Building a learning relationship relies on the learning environment and moving from left to right of the mentoring spectrum sees learning environments becoming increasingly important to the quality and nature of the learning relationship. These learning environments also become more individualised and serve to nurture particular learning relationships within the larger educational environment. This is especially evident in supervision and mentoring [90, 91].

- 4.

Learning assessment

Assessments also play an increasing role moving from left to right of the mentoring spectrum. These assessments must be timely, appropriate and personalised and accompanied by open and frank discussions and personalized, appropriate, specific, timely, holistic, accessible and longitudinal feedback and support [2, 116,117,118,119]. The presence of regular appraisals also reiterate the importance of individualized and safe educational environment [90, 91].

The impact of the mentoring spectrum

An overarching mentoring spectrum combining role modelling, teaching and tutoring, coaching, supervision, and mentoring has wide ramification upon how these educational approaches are employed.

- 1.

The implication upon mentor training is significant. Acknowledging the roles to be played within the mentoring spectrum highlights the need for mentors to be trained in all these educational approaches.

- 2.

The unplanned and unconscious nature of role modelling and the need for balance between personalising and consistency within the mentoring approach both highlight the need for clear standards of practice, codes of conduct and practice guidelines (henceforth Codes of Practice or CoP). There must also be opportunities for mentee and mentors to align expectations and accept their responsibilities and roles and for mentees and mentors to be briefed on the prevailing goals and timelines of their respective educational projects and processes.

- 3.

The learners and tutors must also be appropriately matched to ensure that they have complementary working styles, learning approaches and personalities, goals and abilities [120, 121]. This will help build better educational interactions.

The implications of the mentoring spectrum upon mentoring practice is vast and includes requiring

- i.

mentors-in-training to be trained and skilled on all these educational approaches and be mentored when applying these skill sets and competencies for each of the educational roles.

- ii.

mentors and mentees to be briefed on CoPs, expectations on roles, responsibilities and expectations and effective oversight, assessment, and support provided by the host organization.

- iii.

robust, longitudinal and holistic assessment processes in light of the changing nature of the mentoring process and the mentor’s roles and the presence of evolving mentoring relationships and different stages of the various aspects within the mentoring spectrum.

- iv.

the host organization to take an active role in overseeing and providing personalized, appropriate, specific, timely, holistic, accessible and longitudinal financial and administrative support in running and overseeing the mentoring process given the diverse processes within the mentoring spectrum [2, 116,117,118,119].

- v.

that the mentoring process is sufficiently structured to accommodate for the inevitable changes in the mentoring process without breaching the CoP.

- vi.

the need for a safe and nurturing working environment that will nurture trusting and enduring mentoring relationships that will not only enhance better role modelling when the mentee has established ties with the mentor but also facilitate discussions that extend beyond professional issues which will allow the provision of holistic support.

- vii.

the need for an open and safe mentoring culture that allows open discussions, constructive feedback and frank discussions.

Limitation

This review posits that these practices are interrelated is based on a number of novel yet unproven assumptions. Selecting only four of the many educational roles also limits the scope of understanding of the entire spectrum of educational roles in mentoring. In addition, the practices described in this review focus specific education settings, and draw from a particular definition of role modelling, teaching and tutoring supervision and coaching that may not be applicable in other education settings. Within the context of role modelling for example, there is no consideration of negative role modelling which limits the validity of the conclusions reached. In addition, many of the papers contextualized within the European and American healthcare system and training programs, limit their applicability to other educational and healthcare systems.

Conclusions

The findings of this review not only suggest a new way of conceptualizing mentoring but also highlights the need for further study into the matching, pre-mentoring, mentoring relationship, mentoring evaluations, mentoring structure, the mentoring environment and mentoring culture. This theoretical concept though supported by data from novice mentoring processes will still need to be carefully studied and validated. One key area for further study must be the manner that mentees, mentors and the host organization interact (mentoring dynamics) given its influence upon all processes within the mentoring spectrum. Similarly, important is the design of effective assessment tools and policing of the mentoring process and the mentoring environment.

However, we are confident that this new concept of mentoring will enhance the mentoring process and mentoring outcomes as medical education strives toward personalized medical education.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data generated or analysed in this study can be provided upon request.

Abbreviations

- BEME:

-

Best Evidence Medical Education

- CoP:

-

Codes of Practice

- STORIES:

-

Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis

References

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Herta KD. Formal mentoring programmes for medical students and doctors--a review of the Medline literature. Med Teach. 2006;28(3):248–57.

Sng JH, Pei Y, Toh YP, Peh TY, Neo SH, Krishna LKR. Mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior doctors and/or medical students: a thematic review. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):866–75.

Krishna L, Toh Y, Mason S, Kanesvaran R. Mentoring stages: a study of undergraduate mentoring in palliative medicine in Singapore. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214643–3.

Chong JY, Ching AH, Renganathan Y, Lim WQ, Toh YP, Mason S, Krishna LK. Enhancing mentoring experiences through e-mentoring: a systematic scoping review of e-mentoring programs between 2000 and. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2017;2019:1–32.

Hee JM, Yap HW, Ong ZX, Quek SQM, Toh YP, Mason S, Krishna LKR. Understanding the mentoring environment through thematic analysis of the learning environment in medical education: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019:1–10.

Ikbal MFBM, Wu JT, Wahab MT, Kanesvaran R, LKR K. Mentoring in Palliative Medicine: Guiding Program Design through Thematic Analysis of Mentoring in Internal Medicine between 2000 and 2015. J Palliat Care Med. 2017;7(5).

Yap HW, Chua J, Toh YP, Choi HJ, Mattar S, Kanesvaran R, Krishna LKR. Thematic review of mentoring in occupational therapy and physiotherapy between 2000 and 2015, sitting occupational therapy and physiotherapy in a holistic palliative medicine multidisciplinary mentoring program. J Palliative Care Pediatrics. 2017;2(1):46–55.

Lin J, Chew YR, Toh YP, Krishna LKR. Mentoring in nursing: an integrative review of commentaries, editorials, and perspectives papers. Nurse Educ. 2018;43(1):E1–5.

Loo WTW, Ikbal MFBM, Wu JT, Wahab MT, Yeam CT, Ee HFM, Kanesvaran R, Radha Krishna LK. Towards a Practice Guided Evidence Based Theory of Mentoring in Palliative Care. J Palliat Care Med. 2017;7(1).

Sheri K, Too JYJ, Chuah SEL, Toh YP, Mason S, Krishna LKR. A scoping review of mentor training programs in medicine between 1990 and 2017. Med Edu Online. 2019;24(1):1555435.

Tan B, Toh YL, Toh YP, Kanesvaran R, LKR K. Extending Mentoring in Palliative Medicine-Systematic Review on Peer, Near-Peer and Group Mentoring in General Medicine. J Palliat Care Med. 2017;07(06).

Tan YS, Teo SWA, Pei Y, Sng JH, Yap HW, Toh YP, Krishna LKR. A framework for mentoring of medical students: thematic analysis of mentoring programmes between 2000 and. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2015;2018:1–27.

Toh YP, Karthik R, Teo CC, Suppiah S, Cheung SL, Krishna L. Toward Mentoring in Palliative Social Work: A Narrative Review of Mentoring Programs in Social Work. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2017;35(3):523–31.

Toh YP, Lam BL, Soo J, Chua KLL, Krishna L. Developing Palliative Care Physicians through Mentoring Relationships. Palliat Med Care. 2017;4(1).

Wahab MT, Ikbal MFBM, Wu J, Loo WTW, Kanesvaran R, LKR K. Creating Effective Interprofessional Mentoring Relationships in Palliative Care- Lessons from Medicine, Nursing, Surgery and Social Work. J Palliat Care Med. 2016;06(06).

Wu J, Wahab MT, Ikbal MFBM, Loo TWW, Kanesvaran R, Krishna LKR. Toward an Interprofessional mentoring program in palliative care - a review of undergraduate and postgraduate mentoring in medicine, nursing, surgery and social work. J Palliat Care Med. 2016;06(06):1–11.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Lorenzetti DL, Powelson SE. A scoping review of mentoring programs for academic librarians. J Acad Librariansh. 2015;41(2):186–96.

Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence: methods for studying the delivery and organisation of health services. London: Routledge; 2001.

Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, Rodriguez AM, Ahmed S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:54.

Du Mont J, Macdonald S, Kosa D, Elliot S, Spencer C, Yaffe M. Development of a comprehensive hospital-based elder abuse intervention: an initial systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125105.

Osama T, Brindley D, Majeed A, Murray KA, Shah H, Toumazos M, Van Velthoven M, Car J, Wells G, Meinert E. Teaching the relationship between health and climate change: a systematic scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e020330.

O'Donovan J, O'Donovan C, Kuhn I, Sachs SE, Winters N. Ongoing training of community health workers in low-income andmiddle-income countries: a systematic scoping review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e021467.

Chidwick P, Faith K, Godkin D, Hardingham L. Clinical education of ethicists: the role of a clinical ethics fellowship. BMC medical ethics. 2004;5(1):6.

Pinkus RL, Aumann GM, Kuczewski MG, Medsger A, Meisel A, Parker LS, Wicclair MR: The Consortium Ethics Program: an approach to establishing a permanent regional ethics network. In: HEC forum : an interdisciplinary journal on hospitals' ethical and legal issues: 1995: Springer; 1995: 13–32.

Pape D, Manning S: The educational ladder model for ethics committees: confidence and change flourishing through core competency development. In: HEC forum : an interdisciplinary journal on hospitals' ethical and legal issues: 2006: Springer; 2006: 305–318.

Pinkus RB: The Consortium Ethics Program: Continuing Ethics Education for Community Healthcare Professionals. In: HEC forum : an interdisciplinary journal on hospitals' ethical and legal issues: 1999: Springer; 1999: 233–246.

May T. The breadth of bioethics: Core areas of bioethics education for hospital ethics committees. J Med Philosophy. 2001;26(1):101–18.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):48.

Pham MT, Rajic A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D: The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers' manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. In.; 2015.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Classification of health workforce statistics [Internet]. [http://www.who.int/hrh/statistics/Health_workers_classification.pdf].

Haig A, Dozier M. BEME guide no. 3: systematic searching for evidence in medical education--part 2: constructing searches. Med Teach. 2003;25(5):463–84.

Gordon M, Gibbs T. STORIES statement: publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC Med. 2014;12:143.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J: Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research: springer publishing company; 2006.

Soemantri D, Herrera C, Riquelme A. Measuring the educational environment in health professions studies: a systematic review. Medical teacher. 2010;32(12):947–52.

Schönrock-Adema J, Heijne-Penninga M, van Hell EA, Cohen-Schotanus J. Necessary steps in factor analysis: enhancing validation studies of educational instruments. The PHEEM applied to clerks as an example. Medical teacher. 2009;31(6):e226–32.

Riquelme A, Herrera C, Aranis C, Oporto J, Padilla O. Psychometric analyses and internal consistency of the PHEEM questionnaire to measure the clinical learning environment in the clerkship of a medical School in Chile. Medical teacher. 2009;31(6):e221–5.

Herrera C, Pacheco J, Rosso F, Cisterna C, Daniela A, Becker S, Padilla O, Riquelme A. Evaluation of the undergraduate educational environment in six medical schools in Chile. Revista Med Chile. 2010;138(6):677–84.

Strand P, Sjöborg K, Stalmeijer R, Wichmann-Hansen G, Jakobsson U, Edgren G. Development and psychometric evaluation of the undergraduate clinical education environment measure (UCEEM). Medical Teacher. 2013;35(12):1014–26.

Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72–8.

Cassol H, Pétré B, Degrange S, Martial C, Charland-Verville V, Lallier F, Bragard I, Guillaume M, Laureys S. Qualitative thematic analysis of the phenomenology of near-death experiences. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193001.

Price S, Schofield S. How do junior doctors in the UK learn to provide end of life care: a qualitative evaluation of postgraduate education. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:45.

des Ordons ALR, Lockyer J, Hartwick M, Sarti A, Ajjawi R. An exploration of contextual dimensions impacting goals of care conversations in postgraduate medical education. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15(1):34.

Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalen S, Hult H, Dahlgren LO, Hindbeck H, Ponzer S. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(2):148–53.

Frei E, Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Mentoring programs for medical students--a review of the PubMed literature 2000-2008. BMC medical education. 2010;10:32.

Agarwal R, Sonnad SS, Beery J, Lewin J. Role models in academic radiology: current status and pathways to improvement. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7(1):50–5.

Kravet SJ, Christmas C, Durso S, Parson G, Burkhart K, Wright S. The intersection between clinical excellence and role modeling in medicine. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(4):465–8.

Wright SM, Carrese JA. Excellence in role modelling: insight and perspectives from the pros. CMAJ. 2002;167(6):638–43.

der Leeuw HGAR J-v, Van Dijk N, Wieringa-De Waard M. Assessment of the clinical trainer as a role model: a role model apperception tool (RoMAT). Acad Med. 2014;89(4):671–7.

Côté L, Laughrea PA. Preceptors' understanding and use of role modeling to develop the CanMEDS competencies in residents. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):934–9.

Cote L, Leclere H. How clinical teachers perceive the doctor-patient relationship and themselves as role models. Acad Med. 2000;75(11):1117–24.

Kutob RM, Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D. The diverse functions of role models across primary care specialties. Fam Med. 2006;38(4):244–51.

Wright SM, Carrese JA. Serving as a physician role model for a diverse population of medical learners. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):623–8.

Lombarts KM, Heineman MJ, Arah OA. Good clinical teachers likely to be specialist role models: results from a multicenter cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15202.

Mirhaghi A, Moonaghi HK, Sharafi S, Zeydi AE. Role modeling: a precious heritage in medical education. Acta Facultatis Medicae Naissensis. 2015;32(1):31–42.

Taylor CA, Taylor JC, Stoller JK. The influence of mentorship and role modeling on developing physician-leaders: views of aspiring and established physician-leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1130–4.

Matthews C. Role modelling: how does it influence teaching in family medicine? Med Educ. 2000;34(6):443–8.

Passi V, Johnson S, Peile E, Wright S, Hafferty F, Johnson N. Doctor role modelling in medical education: BEME guide no. 27. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):e1422–36.

Wyber R, Egan T. For better or worse: Role models for New Zealand house officers. N Z Med J. 2007;120(1253):U2518.

Grant A, Robling M. Introducing undergraduate medical teaching into general practice: an action research study. Medical teacher. 2006;28(7):e192–7.

Thuraisingam AI, MacDonald J, Shaw IS. Insights into endoscopy training: a qualitative study of learning experience. Medical teacher. 2006;28(5):453–9.

Parish SJ, Weber CM, Steiner-Grossman P, Milan FB, Burton WB, Marantz PR. APPLIED RESEARCH: teaching clinical skills through videotape review: a randomized trial of group versus individual reviews. Teaching Learning in Med. 2006;18(2):92–8.

Stern DT, Williams BC, Gill A, Gruppen LD, Woolliscroft JO, Grum CM. Is there a relationship between attending physicians' and residents' teaching skills and students' examination scores? Acad Med. 2000;75(11):1144–6.

Carney PA, Dietrich AJ, Eliassen S, Pipas C, Donahue D. Differences in ambulatory teaching and learning by gender match of preceptors and students. Family Med Kansas City. 2000;32(9):618–23.

Laidley TL, Braddock CH, Fihn SD. Did I answer your question? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(1):46–50.

Nagel C, Kirby J, Rushforth B, Pearson D. Foundation programme doctors as teachers. Clin Teach. 2011;8(4):249–53.

George P, Reis S, Dobson M, Nothnagle M. Using a learning coach to develop family medicine residents' goal-setting and reflection skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(2):289–93.

Palamara K, Kauffman C, Stone VE, Bazari H, Donelan K. Promoting success: a professional development coaching program for interns in medicine. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(4):630–7.

McKimm J: Personal Support and Mentoring. In: Essential Guide to Educational Supervision in Postgraduate Medical Education. edn.; 2009: 12–28.

de Figueiredo MN, Rudolph B, Bylund CL, Goelz T, Heußner P, Sattel H, Fritzsche K, Wuensch A. ComOn coaching: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of a varied number of coaching sessions on transfer into clinical practice following communication skills training. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:503.

Wenrich MD, Jackson MB, Maestas RR, Wolfhagen IH, Scherpbier AJ: From cheerleader to coach: The developmental progression of bedside teachers in giving feedback to early learners. Acad Med 2015, 90(11 Association of American Medical Colleges Medical Education Meeting):S91-S97.

Ravitz P, Lancee WJ, Lawson A, Maunder R, Hunter JJ, Leszcz M, McNaughton N, Pain C. Improving physician-patient communication through coaching of simulated encounters. Acad Psych. 2013;37(2):87–93.

Wuensch A, Goelz T, Bertz H, Wirsching M, Fritzsche K. Disclosing information about randomised controlled trials in oncology: training concept and evaluation of an individualised communication skills training for physicians COM-ON-rct. Eur J Cancer Care. 2011;20(5):570–6.

Brinkman WB, Geraghty SR, Lanphear BP, Khoury JC, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Dewitt TG, Britto MT. Effect of multisource feedback on resident communication skills and professionalism: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatrics Adolescent Med. 2007;161(1):44–9.

Schneider S, Kingsolver K, Rosdahl J. Physician coaching to enhance well-being: a qualitative analysis of a pilot intervention. Explore (New York, NY). 2014;10(6):372–9.

Wald HS. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):701–6.

Gonzalez-Guajardo EE, Salinas-Martinez AM, Botello-Garcia A, Mathiew-Quiros A. Clinical coaching in primary care: capable of improving control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus? Primary Care Diabetes. 2016;10(3):171–8.

Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IH, Scherpbier AJ. Cognitive apprenticeship in clinical practice: can it stimulate learning in the opinion of students? Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):535–46.

George P, Rei S, Nothnagle M. Using a learning coach to teach residents evidence-based medicine. Fam Med. 2012;44(5):351–5.

Green DE, Maximin S. Professional coaching in radiology: practice corner. Radiographics. 2015;35(3):971–2.

Kravitz RL. From the editors' desk: improving performance through coaching, incentives, feedback, and practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(4):393–4.

Lin CT, Barley GE, Cifuentes M. Personalized remedial intensive training of one medical student in communication and interview skills. Teach Learn Med. 2001;13(4):232–9.

Fuller G. Do you need a coach? Pract Neurol. 2012;12(1):2–3.

Byyny RL. Mentoring and coaching in medicine. Pharos Alpha Omega Alpha-Honor Med Soc Alpha Omega Alpha. 2012;75(1):1–3.

Cavalcanti RB, Detsky AS. The education and training of future physicians: why coaches can't be judges. JAMA. 2011;306(9):993–4.

Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DH, Snellen-Balendong HA, van Santen-Hoeufft M, Wolfhagen IH, Scherpbier AJ. Clinical teaching based on principles of cognitive apprenticeship: views of experienced clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):861–5.

Byrne JM, Kashner M, Gilman SC, Aron DC, Cannon GW, Chang BK, Godleski L, Golden RM, Henley SS, Holland GJ, et al. Measuring the intensity of resident supervision in the department of veterans affairs: the resident supervision index. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1171–81.

Grant J, Kilminster S, Jolly B, Cottrell D. Clinical supervision of SpRs: where does it happen, when does it happen and is it effective? Specialist registrars. Med Educ. 2003;37(2):140–8.

Kennedy TJT, Lingard L, Baker GR, Kitchen L, Regehr G. Clinical oversight: conceptualizing the relationship between supervision and safety. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1080–5.

Kennedy TJT, Regehr G, Baker GR, Lingard L. Preserving professional credibility: grounded theory study of medical trainees’ requests for clinical support. The BMJ. 2009;338:b128.

Farnan JM, Johnson JK, Meltzer DO, Harris I, Humphrey HJ, Schwartz A, Arora VM. Strategies for effective on-call supervision for internal medicine residents: the superb/safety model. J Graduate Med Educ. 2010;2(1):46–52.

Farnan JM, Petty LA, Georgitis E, Martin S, Chiu E, Prochaska M, Arora VM. A systematic review: the effect of clinical supervision on patient and residency education outcomes. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):428–42.

Farnan JLL, Burger A, Harrison R, Machulsky J, Parekh V, Sharpe B, Schleyer A, Boonyasai R, Arora V. Hospitalists and house staff supervision: a marriage of convenience? J Hosp Med. 2011.

Kilminster SM, Jolly BC. Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: a literature review. Med Educ. 2000;34(10):827–40.

Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod H. Role modeling in Physicians' professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1203–10.

Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. Factors influencing residents’ evaluations of clinical faculty member teaching qualities and role model status. Med Educ. 2012;46(4):381–9.

der Leeuw HGAR J-v, van Dijk N, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Wieringa-de Waard M. The attributes of the clinical trainer as a role model: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(1):26–34.

Recupero PR, Cooney MC, Rayner C, Heru AM, Price M. Supervisor-trainee relationship boundaries in medical education. Med Teacher. 2005;27(6):484–8.

Farnan JM, Burger A, Boonayasai RT, Leykum L, Harrison R, Machulsky J, Parekh V, Sharpe BA, Schleyer AM, Arora VM. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):521–3.

Dominelli GS, Dominelli PB, Rathgeber SL, Webster SB. Effect of different single-session educational modalities on improving medical students' ability to demonstrate proper pressurized metered dose inhaler technique. J Asthma. 2012;49(4):434–9.

Marusic M, Markulin H, Lukic IK, Marusic A. Academic advancement of authors receiving tutoring from a medical journal. Teaching Learning Med. 2006;18(2):126–9.

der Leeuw HGAR J-v, van Dijk N, De Jong W, Wieringa-de Waard M. Educating the clinical trainer: professional gain for the trainee? A controlled intervention study in general practice. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(6):455–73.

Weissmann PF, Branch WT, Gracey CF, Haidet P, Frankel RM. Role modeling humanistic behavior: learning bedside manner from the experts. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):661–7.

Elzubeir MA, Rizk DEE. Identifying characteristics that students, interns and residents look for in their role models. Med Educ. 2001;35(3):272–7.

Branch WT Jr, Kern D, Haidet P, Weissmann P, Gracey CF, Mitchell G, Inui T. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. Jama. 2001;286(9):1067–74.

Gifford KA, Fall LH. Doctor coach: a deliberate practice approach to teaching and learning clinical skills. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):272–6.

Koh GC, Tam JK, Lee JN, Agrawal N, Koh DR, Samarasekera D, Tan CH. Are medical students' views of an ideal physician eroding? A study on perceived qualities of a "role model" doctor before and after housemanship and between two cohorts five years apart. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2015;44(3):79–84.

Steele MM, Fisman S, Davidson B. Mentoring and role models in recruitment and retention: a study of junior medical faculty perceptions. Med Teacher. 2013;35(5):e1130–8.

Boerebach BCM, Lombarts K, Keijzer C, Heineman MJ, Arah OA. The teacher, the physician and the person: How faculty's teaching performance influences their role modelling. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32089.

Stahn B, Harendza S. Role models play the greatest role – a qualitative study on reasons for choosing postgraduate training at a university hospital. GMS Zeitschrift fur Medizinische Ausbildung. 2014;31(4):1–15.

Straus SE, Chatur F, Taylor M. Issues in the mentor-mentee relationship in academic medicine: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):135–9.

Thomas-MacLean R, Hamoline R, Quinlan E, Ramsden VR, Kuzmicz J. Discussing mentorship: an ongoing study for the development of a mentorship program in Saskatchewan. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(7):e263–72.

Hawkins A, Jones K, Stanton A. A mentorship programme for final-year students. Clin Teach. 2014;11(5):345–9.

Areephanthu CJ, Bole R, Stratton T, Kelly TH, Starnes CP, Sawaya BP. Impact of professional student mentored research fellowship on medical education and academic medicine career path. Clin Translational Sci. 2015;8(5):479–83.

Tjan AK. What the best mentors do. Harv Bus Rev. 2017;2(27):17.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital mentoring toolkit & curriculum [http://bwhmentoringtoolkit.partners.org].

Cottrell D, Kilminster S, Jolly B, Grant J. What is effective supervision and how does it happen? A critical incident study. Med Educ. 2002;36(11):1042–9.

Haber LA, Lau CY, Sharpe BA, Arora VM, Farnan JM, Ranji SR. Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision-making, and autonomy. J Hospital Med (Online). 2012;7(8):606–10.

Hauer KE, Oza SK, Kogan JR, Stankiewicz CA, Stenfors-Hayes T, Cate OT, Batt J, O'Sullivan PS. How clinical supervisors develop trust in their trainees: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2015;49(8):783–95.

Goelz T, Wuensch A, Stubenrauch S, Bertz H, Wirsching M, Fritzsche K. Addressing the transition from curative to palliative care: concept and acceptance of a specific communication skills training for physicians in oncology - COM-ON-p. Onkologie. 2010;33(1–2):65–9.

Thorn PM, Raj JM. A culture of coaching: achieving peak performance of individuals and teams in academic health centers. Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1482–3.

Sagasser MH, Kramer AW, van Weel C, van der Vleuten CP. GP supervisors' experience in supporting self-regulated learning: a balancing act. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2015;20(3):727–44.

der Leeuw HGAR J-v, Wieringa-de Waard M, Van Dijk N. Feedback on role model behaviour: effective for clinical trainers? Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(3):153–7.

Loo L, Puri N, Hegstad D, Kawayeh A, Kim D. “Page me if you need me ”-dysfluency on rounds (the wrong message). J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:S56–7.

Tamuz M, Giardina TD, Thomas EJ, Menon S, Singh H. Rethinking resident supervision to improve safety: from hierarchical to interprofessional models. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(8):448–56.

der Leeuw HGAR J-v, Buwalda N, Wieringa-de Waard M, Van Dijk N. Learning from a role model: a cascade or whirlpool effect? Med Teacher. 2015;37(5):482–9.

Kennedy TJ, Regehr G, Baker GR, Lingard LA. Progressive independence in clinical training: a tradition worth defending? Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S106–11.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out as part of the Palliative Medicine Initiative run by the Department of Supportive and Palliative Care at the National Cancer Centre Singapore. The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose advice and feedback greatly improved this manuscript.

Notes of contributors

Associate Professor Lalit Krishna is a Senior Consultant at the Division of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Centre Singapore; Associate Dean for Ethics and Professionalism at Duke-NUS Medical School and Course Director (Phase 4 and 5) at the Centre for Biomedical Ethics, National University of Singapore. A/Prof Krishna is presently undertaking an MD at Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute at the University of Liverpool. Email: lalit.radha-krishna@liverpool.ac.uk

Ms Yaazhini Renganathan is a third year medical student from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, at the National University of Singapore. Email: yaazhini0206@gmail.com

Mr Tay Kuang Teck is a fifth year medical student from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, at the National University of Singapore. Email: taykuangteck@u.nus.edu

Dr Benjamin Tan Jia Xing, MBBS, is a medical officer at the Singapore General Hospital, Singapore. Email: benjamin.tanjx@mohh.com.sg

Ms Chong Jia Yan is a third year medical student from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, at the National University of Singapore. Email: c.jiayan8@gmail.com

Ms Ching Ann Hui is a third year medical student from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, at the National University of Singapore. Email: annhui.ching@gmail.com

Mr Kishore Prakash is a fifth year medical student from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, at the National University of Singapore. Email: kishore@u.nus.edu

Mr Nicholas Quek Wei Sheng is a fifth year medical student from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, at the National University of Singapore. Email: nicholasquekws@u.nus.edu

Dr Rachel Peh Huidi, MBBS, is a medical officer at the National Cancer Centre, Singapore. Email: rachel.peh@mohh.com.sg

Ms Annelissa Chin Mien Chew is a senior librarian at the Medical Library, National University of Singapore Libraries, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: annelissa_chin@nus.edu.sg

Professor David Taylor, BSc, MEd, MA, EdD, PhD, is a Professor of Medical Education and Physiology at Gulf Medical University in Ajman, UAE. Email: dcmt@liverpool.ac.uk

Dr Stephen Mason, PhD PGCHE BA (Hons), is the Research & Development Lead at the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, Academic Palliative & End of Life Care Centre. Email: Stephen.Mason@liverpool.ac.uk

Dr Ravindran Kanesvaran, MRCP (UK), BSc (Hons), MD, FAMS (Med Onco), is a Senior Consultant in the Department of Medical Oncology of the National Cancer Centre Singapore. He is also an Assistant Professor at Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School and clinical senior lecturer at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore. Email: ravindran.kanesvaran@nccs.com.sg

Dr Toh Ying Pin, MBBS, MRCPaed, is a resident in the Department of Family Medicine at National University Health System, Singapore. Email address: yingpintoh@gmail.com

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LK, YP, KT, BT, JY, AH, KP, NQ, and RP contributed to the research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis and results synthesis, manuscript writing and review, and administrative work for the journal submission. AC contributed to the conceptualizing and developing of search strategy and methodological design. DT, SM, YP, and RK contributed to the research design, data analysis, methodology, results, and manuscript review. LK, RP, RK, YP, and KT were also involved in mentoring and research team management. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Radha Krishna, L.K., Renganathan, Y., Tay, K. et al. Educational roles as a continuum of mentoring’s role in medicine – a systematic review and thematic analysis of educational studies from 2000 to 2018. BMC Med Educ 19, 439 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1872-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1872-8