Abstract

Background

Use of podcasts has several advantages in medical education. Podcasts can be of different types based on their length: short (1–5 min), moderate (6–15 min) and long (>15 min) duration. Short-duration podcasts are unique since they can deliver high-yield information in a short time. The perceptions of medical students towards short-duration podcasts are not well understood and this study aimed to analyze the same. An exploratory analysis of students’ podcast usage and performance in summative assessments was also undertaken.

Methods

First-year medical students (N = 94) participated in the study. Eight audiovisual podcasts, each ≤3 min duration (3-MinuTe Lessons; 3MTLs) were developed for two topics in biochemistry. The podcasts were made available for students after didactic lectures on the topics. Feedback was collected from students about their perceptions to 3MTLs using a self-reported questionnaire. The scores of students in summative assessments were compared based on their usage of 3MTLs.

Results

Feedback revealed that 3MTLs were well received by students as a useful and convenient supplementary tool. Students used 3MTLs for topic review, to get an overview, as well as for quick revision and felt that 3MTLs were helpful in improving their understanding of the topic, clarify concepts and focus on important points and in turn, in preparation for assessments. A significant proportion (49%) felt that 3-min duration was optimal while, an equal proportion suggested an increase in the duration to 5 min with more information. The overall mean scores in assessments were not different between students based on 3MTLs usage. The pairwise comparisons revealed better scores amongst students who used 3MTLs for both topics.

Conclusion

Overall, short-duration podcasts were perceived by students as useful supplementary learning tools that aided them for revision and in preparation for assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Biochemistry is considered by medical students as a difficult subject to study, while it’s also an equally challenging task for the teachers to teach [1]. Unlike the subjects where it may be possible for students to correlate with specimens, dissections, or real life examples, conceptualization in biochemistry is often, a challenge [1]. Traditional didactic teaching and textbooks may not suit all students since learning preferences are different among individuals [2]. The new generation of medical students is more proficient with the use of technology. Hence, educators need to come up with strategies to assist self-learning [3]. In this context, podcasts can be a useful educational technology that can cater to learners with auditory, visual or mixed learning preferences [4]. The term ‘podcast,’ now refers to audio/video files that can be downloaded or streamed on portable media players [5]. Podcasting was initially developed for entertainment but has been tried in the fields of medical, dental, nursing and veterinary education [6,7,8,9]. Understandably, students have the advantage to access podcasts by devices of their choice (smartphones, tablets, and computers). Since podcasts can be used anywhere, anytime, they enable students to learn at their pace [5, 10].

There is a notable enthusiasm among educators for the adoption of podcasts into medical education [11,12,13]. On the other hand, a few educators also raise caution in using podcasts, citing lack of credible evidence [14]. Additionally, the success of this technology also depends on other factors such as the purpose of podcasts, type of podcasts, mode of delivery, target audience, etc. Hence, there are still gaps in our understanding of the utility of podcasts in medical education. Despite the available evidence to support the use of podcasts, currently, there is no defined role for it in medical education [14]. The consensus is that podcasting should be used to complement rather than replace traditional teaching for a richer learning experience [6, 12, 15].

In the past, several studies have used podcasts in medical education for different purposes. Podcasts have been tried as a teaching method in comparison to traditional didactic teaching [8, 16,17,18,19,20,21] or text-based learning [22, 23]. Most other investigators have used podcasts as tools to supplement routine teaching practices [6, 7, 10, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Alternatively, a few investigators have tried podcasts as a preparatory tool for “flipped-classroom” which allows teaching hours to be utilized for problem-solving interactions [35, 36].

An additional factor that can influence the success of podcasts, albeit less studied, is the length of podcasts. Based on a classification by Carvalho et al., podcasts can be of different types based on their length: short (1–5 min), moderate (6–15 min) and long (>15 min) duration [37]. A common practice among several universities has been to record and provide entire lecture sessions, analogous to long-duration podcasts [38,39,40]. However, it is known that long duration podcasts are less preferred by listeners [41]. The general recommendation is to maintain the length of podcasts <15 min, considering the attention span of listeners [37, 38, 42]. In the past, several researchers have mainly used moderate-duration podcasts for their investigation [6, 8, 27, 29, 30, 34]. Short-duration podcasts are less studied, and there are only a few studies in this regard [28, 43, 44]. Aguiar et al. used short-duration podcasts for delivering learning outcomes and guidelines for reading the topic without providing any conceptual information, as such [43]. In a study by Narula et al., clinical clerks were provided with 5-min podcasts each designed to cover a selected core internal medicine concept [28]. Another study used short-duration podcasts for information delivery and student feedback on evolution and heredity topics [44]. However, students’ perceptions towards short-duration podcasts are less understood.

Short-duration podcasts are unique since they are capsules of high-yield information for students to review quickly. However, an inherent disadvantage of short-duration podcasts is the limited information that can be conveyed due to the time barrier. This factor can be critical from the students’ perspective; because gathering information within short-duration may require some prior knowledge on the topic. Hence, it is important to analyze the usefulness of podcasts among medical students. This pilot study was undertaken to analyze the perceptions and preferences of medical students towards short-duration podcasts in biochemistry. An exploratory analysis of students’ usage of podcasts and its impact on performance in summative assessments was also undertaken.

Methods

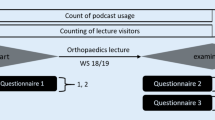

The study was conducted in the Department of Biochemistry at Christian Medical College, Vellore, India from December 2015 to March 2016. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). First-year medical students (N = 100) from the Batch of 2015 from the institution were invited to participate in the study. Since the investigator (AR) and participants were acquainted with each other, the study had a post-positivistic approach. The investigator’s speculation was that short-duration podcasts would be useful as supplementary learning tools.

Podcast development and delivery

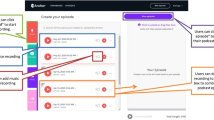

A decision on the type of podcast to be used for this study was based on the taxonomy proposed earlier [37]. Accordingly, the type of podcasts was informative; the medium was videos of short-duration (≤ 3 min per episode), the author was the investigator (AR) himself, the style was formal, and the purpose was to inform. All podcasts (3-MinuTe Lessons; 3MTLs) consisted of a graphical slide show with a video inset of the narrator in each slide. The slide show was created using Microsoft PowerPoint™ (Microsoft, WA, USA) and audio-visual component was recorded using Office Mix™ (Microsoft, WA, USA). The script for the podcasts was written in advance, tailored to fit the time-frame and was read out by the investigator during the recording.

Initially, a pilot episode was recorded by the investigator. Faculty members (n = 5), postgraduate students (n = 3) and second-year medical students (n = 3) from the institution were invited to review the pilot podcast and provide an informal feedback (data not shown). Subsequently, eight 3MTLs were developed for two topics taught under biochemistry curriculum (Table 1). The content of 3MTLs was designed in such a way that only brief highlights of the topics were covered. All 3MTLs used in this study had 320 × 240 image resolution with file sizes between 6.2 to 8.8 MB such that they would be optimal for use with small screen devices without occupying a lot of storage space. Production of each 3MTL required around 6–8 h inclusive of planning, rehearsal sessions, and final recording.

The topics were initially delivered as lectures of 1-h duration each, by the investigator (AR) on eight different occasions (Table 1). Subsequent to each lecture, 3MTL on the topic was made available on the institution’s e-learning portal (http://e-learning.cmcvellore.ac.in). This education portal was developed in collaboration with Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, on an open source platform called the Tufts University Sciences Knowledge Base (TUSK) (for more details on the portal, refer to [45, 46]). After the upload of the first 3MTL in the series, students were announced about the availability of 3MTLs in the e-learning portal and mode of access. Students were allowed to stream and download 3MTLs without restrictions. As per routine practice, lecture slides were also made available for the students. Written assessments were conducted as part of the students’ ongoing schedule. Cumulative data on students’ usage was monitored using a tracking option available in the e-learning portal.

Survey

Feedback was collected in a classroom setting from the students who provided informed consent. A two-part questionnaire developed for this study was used for data collection. The questionnaire was reviewed for construct validity by two faculty members and two postgraduate students not involved in the study. Part A questionnaire was designed to obtain anonymous feedback and suggestions from students and contained two open-ended items (A1 and A2). Part B questionnaire (Additional file 1) was designed to collect specific data with closed-ended items (B1-B16). Items B1 to B8 were questions about the educational background of students (B1-B4) and their study habits (B5-B8). Items B9-B13 were designed to assess the pattern of usage of 3MTLs by the students. A 5-point Likert scale was used for B14 (where, 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good and 5 = excellent) and B15 (where, 1 = not useful, 2 = somewhat useful, 3 = useful, 4 = very useful and 5 = extremely useful) to assess the quality of 3MTLs and their usefulness from the students’ perspective, respectively. The aspects evaluated in B14 were clarity of presentation, use of simple, clear language, adequacy of content, quality of audio, quality of video and ease of downloading (streaming) on e-learning. Item B16 asked students if they would recommend 3MTLs for other topics in the future. Data was extracted from the completed questionnaires and participants were anonymized for analysis.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data analysis for responses from items A1 and A2 were carried out using a previously published coding scheme after adaptation [47]. The qualitative analysis of both items was scored on 5-point rating scale under three major categories: learning, engagement, and quality, each of which was further subcategorized. The coding scheme used for analysis is shown in Table 2. All responses by students were rated for each subcategory by two raters independently (SSP and MN) and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The average rating was calculated for each subcategory, and total effect of each was calculated by multiplying the average rating by the total number of students who commented on the respective subcategory.

Quantitative analysis

Students were divided into 3 groups based on self-reported 3MTL usage [3MTL: Heavy-users (used 3MTLs for two topics); 3MTL: Intermediate-users (used 3MTLs for one topic); 3MTL: Non-users (did not use 3MTLs)]. Assessment scores of students were obtained from departmental records. Data integrity was verified by random cross checking at two different time points. The impact of 3MTL usage was studied by comparing scores obtained by students in written assessments. Each assessment constituted a written test for a maximum score of 30 and absolute scores obtained by students were used for quantitative analysis. The assessment questions were essay and short answer descriptive type, testing a combination of factual recall and application-based knowledge. Faculty members in the department (including investigators on a rotational basis, as per departmental policy) were involved in the design of questions for assessment and scoring the answer scripts. Questions used in assessments were screened for construct validity by a faculty member not part of the study.

Test3MTL denotes the assessment conducted on topics in Table 1 (which had 3MTL supplementation). TestP and TestS refer to the assessments that immediately preceded and succeeded Test3MTL, respectively. Scores of students in 5 historic assessments (conducted before TestP) were also obtained. Although each of the assessments covered different modules (Additional file 5: Table S4), the pattern of assessments was similar. Only topics covered for Test3MTL had podcast supplementation; also, content for Test3MTL as well as other assessments was based on curricular requirements and not strictly on the learning outcomes of 3MTLs.

To study intra-individual changes, pairwise comparison of scores were calculated (Test3MTL minus TestP; Test3MTL minus TestS). For instance, if a student’s score in TestP, Test3MTL and TestS was 24, 27 and 23, respectively, the pair differences in scores would be: Test3MTL minus TestP = 3 and Test3MTL minus TestS = 4. Subsequently, an average of the pairwise differences in scores was calculated for 3MTL: Heavy-users, Intermediate-users, and Non-users. To test if a subset of students in 3MTL: Heavy-users may be the primary beneficiaries of 3MTLs accounting for the above observation, 3MTL: Heavy-users were further sub-classified into tertiles based on their average scores in historical assessments as Below-average performers, Average performers, and Above-average performers.

Statistical analysis

Likert scale data were handled as ordinal data [48]. Parametric tests were used for analysis. ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s posthoc test used for comparison of Test3MTL scores between different groups. For pairwise comparisons (Test3MTL vs TestP/ Test3MTL vs TestS), paired t-test was used. All statistical analyses were done with SPSS v. 16 software. Reporting of the study is as per Standards for Reporting of Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines [49] considering additional recommendations related to medical education research [50,51,52].

Results

Ninety-four students consented to participate in the study. Feedback indicated that 41 students (43.6%) used 3MTLs for both topics, 34 students (36.2%) used for one of the topics while 19 students (20.2%) did not use 3MTLs. The usage statistics from the e-learning portal indicated that at the end of the study period, the total numbers of views and visitors for 3MTLs were 477 and 308, respectively (Table 1).

Ninety-one students responded for Item A1 of feedback questionnaire which asked ‘Did you find the 3-Minute Lesson videos useful? Please elaborate,’ and 79 students (86.8%) mentioned that 3MTLs were useful. Summary of comments for item A1 is shown in Table 3 (for detailed comments, see Additional file 2: Table S1). Qualitative analysis for item A1 revealed that the majority of students’ comments were about learning category, specifically to help offered by 3MTLs for revision, preparation for assessments and general learning which were rated the top 3 subcategories. A few students specified 3MTLs were helpful in gaining an overview of the topic and studying. A few students also mentioned the advantage of the short-duration of the podcasts and the teacher’s voice in the audio component. In the engagement category, some students specified that 3MTLs were more useful and engaging compared to reading textbooks or lecture slides. Very few comments from students were about the quality aspects of the podcasts. Of note, the students’ ability to control the podcasts and convenience in using them were mentioned by a few students. Technological issues faced by students in using 3MTLs was rated the lowest among all subcategories. Eleven students who indicated they did not use 3MTLs, specified reasons such as, they ‘prefer reading’ and that ‘slides were easier to download.’

Item A2 was ‘What suggestions do you have to improve the 3-Minute Lesson videos?’ and it received 76 responses. Summary of responses to item A2 is shown in Table 4 (for detailed comments, see Additional file 3: Table S2). In the learning category, the majority of students’ comments suggested improving the challenge component of 3MTLs by including more concepts and extending to other complex topics in biochemistry. Another suggestion was to increase the duration of podcasts. In the engagement category, the major suggestion was to address the technological issues in using 3MTLs by making them easier to download and decreasing the size of the files. A few students also suggested increasing the interactivity of podcasts. In the quality category, the suggestions were to improve the quality of audio, video, and graphics used in 3MTLs.

For analysis of responses from the Part B questionnaire (for data from items B1 to B10, see Additional file 4: Table S3), students who indicated they did not use 3MTLs for either of the topics (n = 19) were excluded. The majority of responses indicated that students used 3MTLs for revision while, a smaller percentage also used it for orientation, and studying (Fig. 1i). Smartphones and laptops were the major gadgets used by students to access 3MTLs (Fig. 1ii). When questioned about their perception of the length of the podcast, 37 students (49.3%; Fig. 1iii) indicated that the time duration of podcasts was optimal, while an equal proportion felt that duration can be increased, preferably to 5 min. Mean scores on the rating of the quality of 3MTLs were lowest for ease of downloading (streaming) on e-learning and highest for the use of simple, clear language (Fig. 2). Mean scores for the usefulness of 3MTLs were lowest for motivation obtained to the read the topic and highest for helping to prepare for the test (Fig. 2). Also, an overwhelming majority (96%; n = 72) of students indicated that they would recommend 3MTLs for other topics in future.

Overall, average scores in Test3MTL were not different when compared with TestP or TestS or among student groups based on 3MTLs usage (Fig. 3). However, the difference of scores in pairwise comparisons (Test3MTL vs. TestP; Test3MTL vs. TestS) was statistically significant (Table 3). In the pairwise comparisons with students groups stratified based on 3MTL usage, the difference was significant amongst 3MTL: Heavy-users in Test3MTL vs. TestP. In the comparison of Test3MTL vs. TestS, all three subgroups showed significant pairwise differences. Also, the magnitude of the score difference amongst 3MTL: Heavy-users in pairwise comparisons were higher than both Intermediate and Non-users (Table 5). Further, 3MTL: Heavy-users were sub-classified into tertiles based on their average scores in historical assessments and pairwise comparisons were repeated (Additional file 5: Table S4). Notably, only the Above-average performers among the 3MTL: Heavy-users had consistently higher pairwise scores in the Test3MTL vs. TestP and Test3MTL vs. TestS comparisons (Table 5). Other demographic characteristics were similar in the subgroups of 3MTL: Heavy-users (data not shown).

Comparison of scores of students in written assessments. i) Scores in the test (Test3MTL) which had implemented 3MTLs were compared with assessments that immediately preceded (TestP) and succeeded (TestS). Tests were scored out of a maximum of 30. Data is represented as mean ± SD in all groups (N = 92). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. ii) Based on self-reported 3MTL usage, students were divided into 3 groups for comparison [3MTL: Heavy-users (used 3MTLs for two topics; N = 41); 3MTL: Intermediate-users (used 3MTLs for some of the topics; N = 32); 3MTL: Non-users (did not use 3MTLs; N = 19)]. Tests were scored out of a maximum of 30. Data is represented as mean ± SD in all groups. NS- Not significant

Discussion

This pilot study was designed to analyze the perceptions of medical students to short-duration podcasts in biochemistry. Specifically, the study was designed to analyze how and why students accessed podcasts and their experiences in the process. Additionally, an exploratory analysis of the use of podcasts and students’ performance in the assessments was also done. Overall, podcasts were well received in this study and students perceived 3MTLs mainly as a supplementary learning tool. Students felt that 3MTLs were a valuable addition to routine teaching practice and suggested extending it to other topics. The results of the qualitative and quantitative analysis indicated that students mainly used 3MTLs for revision purpose after having read the topic. Particularly, students reported using 3MTLs for a quick review before assessments. This aspect was corroborated with a spike in the number of visitors and views of 3MTLs a day before assessment in the e-learning portal (data not shown). A smaller proportion of students used 3MTLs as a preparatory tool for gaining a topic overview. Additionally, students also felt that 3MTLs were helpful in improving their understanding of the topic, clarify concepts and focus on important points. These findings are consistent with other previous studies involving podcasts [5, 24, 30,31,32, 53].

Interestingly, half of the students perceived that the length of podcasts was optimum while an equal proportion suggested that the duration of podcasts can be increased to about 5 min. The survey by Matava et al. showed that podcast listeners preferred different podcast durations depending on the content [41]. For case presentations, procedural skills, journal article summaries, and discussions, the preferred podcast duration were 5–15 min, while for recorded lectures, a 15–30 min podcast was preferred; podcasts >45 min were least preferred. Matava et al. explain this observation as “respondents perceive that a certain amount of time is necessary to convey key learning objectives” [41].

Respondents in our study also indicated a preference to the audio and visual component in podcasts similar to few earlier observations [5, 34, 41]. Students noted that the teacher’s voice-over in the background was reassuring and useful in learning while the visual component in the podcasts made them lively. A few students felt that 3MTLs were more useful and interesting compared with reading texts. However, these observations were not shared by the majority, and a few students specified their preference to reading as the reason for not using 3MTLs. These observations further reiterate about different learning preferences among students. Certainly, the inclusion of audio-visual component in podcasts would be advantageous for students with aural, visual or multimodal learning preferences [2].

It was noted that the majority of students reported using smartphones to access 3MTLs followed by laptops. This observation was an interesting contrast since, several studies conducted before 2014 have reported that podcasts were accessed by listeners mainly through computers followed by portable media players [5, 6, 10, 31,32,33, 37, 41, 54,55,56,57]. However, general podcast listenership trends in the USA and UK has shown a shift towards smartphones after 2014 [58, 59]. Keeping in line with this trend, the more recent studies in medical education also indicate that podcasts are mainly accessed through smartphones over computers [60, 61] and our results corroborate with this observation.

Attention to technological issues of podcasts and their perceptions to users are important. Earlier observations show that technological issues are often cited by students as barriers to accessing podcasts [32]. Findings from this present study also indicate technical issues: ease of downloading (streaming) 3MTLs had lower ratings (Fig. 2 ii) and several students who did not access podcasts cited download issues and bigger file size as reasons. Additionally, the ease of downloading was rated lower among students who accessed 3MTLs on phones compared to computers (data not shown). A probable reason for this could be that podcasts were made available through the institution’s e-learning portal, a website best suited for use with computers. An alternative option to overcoming issues with the medium of delivery would be to make podcasts available through more than one portal that allows video streaming (e.g., YouTube, Facebook). Other device-related technical factors could be issues related to internet connectivity, server, browser compatibility, device’s storage capacity, software or hardware. Concerning the format of podcasts, the major feedback provided by students in this study was towards the improvement of audio and video quality. A major reason could be that only basic equipment was used for recording the podcasts. The investigator’s lack of experience in podcasting could be another contributing factor. Also, 3MTLs were made available in 320 × 240 image resolution ideally suited for viewing in handheld gadgets. It is possible that students who accessed podcasts on devices with larger screens may have rated the video quality lower. However, production of high-quality video podcasts would also require more preparation time, costlier recording equipment, and larger file sizes, amongst other factors. The costs and benefits would need to be weighed while considering the production of video podcasts. However, it is important for podcasters to be aware of these issues while deciding on the format and medium of delivery of podcasts.

An exploratory comparison of scores in summative assessments also suggested that use of 3MTLs was associated with better performance. A few studies in the past have used a pre-test-post-test quiz to assess the effectiveness of podcast implementation in comparison to lecture-teaching and showed weak evidence for improvement in podcast group [25,26,27]. Comparison between teaching with lectures and video podcasts by a crossover trial observed that student evaluations were not different between the two formats [8]. In this study, the overall mean scores were not different between students based on 3MTLs usage, suggesting that factual recall is similar amongst students, irrespective of podcast usage. However, the pairwise comparisons revealed better scores amongst 3MTL: Heavy users. It is further possible that a subset of students in 3MTL: Heavy-users may be the primary beneficiaries of 3MTLs since sub-stratification of 3MTL: Heavy users showed that benefit was consistently observed only amongst ‘Above-average performers.’

Some potential confounders of this study are factors about the student’s background related to school education, study habits, learning preferences, and availability of gadgets to access 3MTLs (Additional file 6). The questionnaire was designed to collect information on some of the above factors, but, no patterns were detected in the use of 3MTLs (data not shown). Participants were recruited by convenience sampling, and hence there is a possible sampling bias in the study. There is a possibility of response bias considering that investigator (AR) and participants are well acquainted and AR was also involved in the delivery of lectures, creation on 3MTLs and feedback collection. Another limitation of this study would be the lack of baseline pre-test scores on the topics under study. Finally, data on the total number of views and visitors from the website statistics may be an underestimate, since it does not account for files downloaded and transferred to students by other means. In comparison to previous studies, there are also a few aspects of the methodology of this current study that are worth mention. A major difference would be that fixed, short-duration podcasts aimed at providing highlights of the topic were used in this study, while others have used moderate- or long-duration podcasts [8, 25, 30, 34]. Also, in this study 3MTLs were only provided as a supplementary tool, and hence, assessments were held as per routine teaching schedule, and no additional assessments (specifically related to 3MTLs) were conducted.

Authors’ perspectives

Informal feedback from medical students at CMC, Vellore often suggests that students find biochemistry a difficult subject to study and remember. Lecture capture is not practiced in the author’s institution, and hence students are limited to, lectures and text-based learning resources. The idea for developing podcasts evolved to provide additional resources for students with different learning preferences. The inspiration of the time frame was partly from the Three Minute Thesis competition conducted by University of Queensland, Australia (https://threeminutethesis.uq.edu.au/). The responses from faculty and students for pilot podcast episode were motivating, and the idea eventually evolved to cover the entire module. The author’s department and institution were supportive, however, no additional resources were obtained from any source. The podcast recording and delivery were done by the author himself using his personal equipment. Planning and creation of each podcast episode required about 6–8 h. The script for the podcast was written in advance and rehearsed multiple times to ensure it fits the time frame. The author found the implementation of podcasts in his teaching module was, by itself, an enriching experience. Though podcast development is laborious, they can be reusable tools to deliver high-yield information to students and may also partly relieve the burden on faculty occupied with clinical, research or administrative responsibilities. In institutions, that do not follow lecture-capture approach, short and moderate-duration podcasts can be useful alternatives.

Conclusion

To conclude, short-duration podcasts are useful supplementary tools in medical education. Analysis of the feedback from students suggests that they consider podcasts as a very useful tool for review and preparation for assessments. The authors’ beliefs about the future of this media concur with others who view podcasts as a supplementary learning tool but not meant to replace traditional teaching.

Abbreviations

- 3MTL:

-

3-minute lesson

- SRQR:

-

Standards for Reporting of Qualitative Research

References

Wood EJ. Biochemistry is a difficult subject for both student and teacher. Biochem Educ. 1990;18(4):170–2.

Fleming ND. I'm different; not dumb. Modes of presentation (VARK) in the tertiary classroom. In: Research and Development in Higher Education, Proceedings of the1995 Annual Conference of the Higher Education and Research Development Society of Australasia (HERDSA): 1995; 1995: 308–313.

Kennedy G, Gray K, Tse J. 'Net Generation' medical students: technological experiences of pre-clinical and clinical students. Med Teach. 2008;30(1):10–6.

Zapalska A, Brozik D. Learning styles and online education. Campus Wide Inf Syst. 2006;23(5):325–35.

Copley J. Audio and video podcasts of lectures for campus-based students: production and evaluation of student use. Innov Educ Teach Int. 2007;44(4):387–99.

Walmsley AD, Lambe CS, Perryer DG, Hill KB. Podcasts--an adjunct to the teaching of dentistry. Br Dent J. 2009;206(3):157–60.

Kardong-Edgren S, Emerson R. Student adoption and perception of lecture podcasts in undergraduate bachelor of science in nursing courses. J Nurs Educ. 2010;49(7):398–401.

Schreiber BE, Fukuta J, Gordon F. Live lecture versus video podcast in undergraduate medical education: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:68.

Gough KC. Enhanced podcasts for teaching biochemistry to veterinary students. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2011;39(6):421–5.

Evans C. The effectiveness of m-learning in the form of podcast revision lectures in higher education. Comput Educ. 2008;50(2):491–8.

Rainsbury JW, McDonnell SM. Podcasts: an educational revolution in the making? J R Soc Med. 2006;99(9):481–2.

White J, Sharma N. Podcasting: a technology, not a toy. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2012;17(4):601–3.

Long SR, Edwards PB. Podcasting: making waves in millennial education. J Nurs Staff Dev. 2010;26(3):96–101. quiz 102-103

Zanussi L, Paget M, Tworek J, McLaughlin K. Podcasting in medical education: can we turn this toy into an effective learning tool? Adv Health Sci Educ. 2012;17(4):597–600.

Jham BC, Duraes GV, Strassler HE, Sensi LG. Joining the podcast revolution. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(3):278–81.

McKinney AA, Page K. Podcasts and videostreaming: Useful tools to facilitate learning of pathophysiology in undergraduate nurse education? Nurse Educ Pract. 2009;9(6):372–6.

Vogt M, Schaffner B, Ribar A, Chavez R. The impact of podcasting on the learning and satisfaction of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2010;10(1):38–42.

Nast A, Schafer-Hesterberg G, Zielke H, Sterry W, Rzany B. Online lectures for students in dermatology: a replacement for traditional teaching or a valuable addition? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(9):1039–43.

Florescu CC, Mullen JA, Nguyen VM, Sanders BE, Vu PQ. Evaluating Didactic Methods for Training Medical Students in the Use of Bedside Ultrasound for Clinical Practice at a Faculty of Medicine in Romania. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34(10):1873–82.

Bhatti I, Jones K, Richardson L, Foreman D, Lund J, Tierney G. E-learning vs lecture: which is the best approach to surgical teaching? Color Dis. 2011;13(4):459–62.

Bensalem-Owen M, Chau DF, Sardam SC, Fahy BG. Education research: evaluating the use of podcasting for residents during EEG instruction: a pilot study. Neurology. 2011;77(8):e42–4.

Back DA, von Malotky J, Sostmann K, Hube R, Peters H, Hoff E. Superior Gain in Knowledge by Podcasts Versus Text-Based Learning in Teaching Orthopedics: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(1):154–60.

Edmond M, Neville F, Khalil HS. A comparison of teaching three common ear, nose, and throat conditions to medical students through video podcasts and written handouts: a pilot study. Adv Med Edu Pract. 2016;7:281–6.

Brittain S, Glowacki P, Van Ittersum J, Johnson L. Podcasting Lectures. Educ Q. 2006;3:24–31.

Kalludi S, Punja D, Rao R, Dhar M. Is Video Podcast Supplementation as a Learning Aid Beneficial to Dental Students? J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(12):CC04–7.

Kalludi SN, Punja D, Pai KM, Dhar M. Efficacy and perceived utility of podcasts as a supplementary teaching aid among first-year dental students. Australas Med J. 2013;6(9):450–7.

O'Neill E, Power A, Stevens N, Humphreys H. Effectiveness of podcasts as an adjunct learning strategy in teaching clinical microbiology among medical students. J Hospital Infection. 2010;75(1):83–4.

Narula N, Ahmed L, Rudkowski J. An evaluation of the '5 Minute Medicine' video podcast series compared to conventional medical resources for the internal medicine clerkship. Med Teach. 2012;34(11):e751–5.

White JS, Sharma N, Boora P. Surgery 101: evaluating the use of podcasting in a general surgery clerkship. Med Teach. 2011;33(11):941–3.

Pilarski PP, Alan Johnstone D, Pettepher CC, Osheroff N. From music to macromolecules: using rich media/podcast lecture recordings to enhance the preclinical educational experience. Med Teach. 2008;30(6):630–2.

Meade O, Bowskill D, Lymn JS. Pharmacology as a foreign language: a preliminary evaluation of podcasting as a supplementary learning tool for non-medical prescribing students. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:74.

Meade O, Bowskill D, Lymn JS. Pharmacology podcasts: a qualitative study of non-medical prescribing students' use, perceptions and impact on learning. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:2.

Mostyn A, Jenkinson CM, McCormick D, Meade O, Lymn JS. An exploration of student experiences of using biology podcasts in nursing training. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:12.

Shantikumar S. From lecture theatre to portable media: students' perceptions of an enhanced podcast for revision. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):535–8.

Mellefont L, Fei J. Using echo360 Personal Capture Software to Create a ‘Flipped’ Classroom for Microbiology Laboratory Classes. ASCILITE. 2014:534–8.

Raupach T, Grefe C, Brown J, Meyer K, Schuelper N, Anders S. Moving Knowledge Acquisition From the Lecture Hall to the Student Home: A Prospective Intervention Study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(9):e223.

Carvalho AA, Aguiar C, Santos H, Oliveira L, Marques A, Maciel R. Podcasts in Higher Education: Students’ and Lecturers’ Perspectives. In: Tatnall A, Jones A, editors. Education and Technology for a Better World: 9th IFIP TC 3 World Conference on Computers in Education, WCCE 2009, Bento Gonçalves, Brazil, July 27–31, 2009 Proceedings. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2009. p. 417–26.

Sandars J. Twelve tips for using podcasts in medical education. Med Teach. 2009;31(5):387–9.

Shaw GP, Molnar D. Non-native English language speakers benefit most from the use of lecture capture in medical school. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2011;39(6):416–20.

Horvath Z, O'Donnell JA, Johnson LA, Karimbux NY, Shuler CF, Spallek H. Use of lecture recordings in dental education: assessment of status quo and recommendations. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(11):1431–42.

Matava CT, Rosen D, Siu E, Bould DM. eLearning among Canadian anesthesia residents: a survey of podcast use and content needs. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:59.

Lee M, Chan A. Reducing the effects of isolation and promoting inclusivity for distance learners through podcasting. Turk Online J Distance Educ. 2007;8(1):85–104.

Aguiar C, Carvalho AA, Carvalho CJ. Use of short podcasts to reinforce learning outcomes in biology. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2009;37(5):287–9.

Almeida-Aguiar C, Carvalho AA. Exploring podcasting in heredity and evolution teaching. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2016;44(5):429–32.

Varghese J, Faith M, Jacob M. Impact of e-resources on learning in biochemistry: first-year medical students' perceptions. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:21.

Lee MY, Albright S, O'Leary L, Terkla DG, Wilson N. Expanding the reach of health sciences education and empowering others: the OpenCourseWare initiative at Tufts University. Med Teach. 2008;30(2):159–63.

Kay RH, Knaack L. An examination of the impact of learning objects in secondary school. J Comput Assist Learn. 2008;24(6):447–61.

Jamieson S. Likert scales: how to (ab)use them. Med Educ. 2004;38(12):1217–8.

O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51.

Tavakol M, Sandars J. Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part I. Med Teach. 2014;36(9):746–56.

Tavakol M, Sandars J. Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part II. Med Teach. 2014;36(10):838–48.

Coverdale JH, Roberts LW, Balon R, Beresin EV. Writing for academia: getting your research into print: AMEE Guide No. 74. Med Teach. 2013;35(2):e926–34.

Lonn S, Teasley SD. Podcasting in higher education: What are the implications for teaching and learning? Internet High Educ. 2009;12(2):88–92.

Hill J, Nelson A, France D, Woodland W. Integrating Podcast Technology Effectively into Student Learning: A Reflexive Examination. J Geogr High Educ. 2012;36(3):437–54.

Lyles H, Robertson B, Mangino M, Cox JR. Audio podcasting in a tablet PC-enhanced biochemistry course. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2007;35(6):456–61.

Taylor MZ. Podcast Lectures as a Primary Teaching Technology: Results of a One-Year Trial. J Pol Sci Educ. 2009;5(2):119–37.

Malan D: Podcasting Computer Science E-1. In: In SIGCSE 2007: Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education: March 7–10, 2007 2007; Covington, Kentucky; 2007.

The podcast consumer 2016. [http://www.edisonresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/The-Podcast-Consumer-2016.pdf].

Device distribution of podcast listening time in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2016 [https://www.statista.com/statistics/412226/podcast-listening-by-device-uk/].

Nwosu AC, Monnery D, Reid VL, Chapman L. Use of podcast technology to facilitate education, communication and dissemination in palliative care: the development of the AmiPal podcast. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(2):212–7.

Riddell J, Swaminathan A, Lee M, Mohamed A, Rogers R, Rezaie SR. A Survey of Emergency Medicine Residents' Use of Educational Podcasts. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(2):229–34.

Acknowledgments

The investigator would like to thank and acknowledge the inputs of Dr. Molly Jacob (Professor, Department of Biochemistry) and Dr. Vinay Oommen (Associate Professor, Department of Physiology) Christian Medical College, Vellore towards the development of 3MTLs. Following members from Christian Medical College, Vellore provided feedback for the pilot video: Dr. Molly Jacob, Dr. Joe Varghese (Professor, Department of Biochemistry), Dr. Vinay Oommen; Drs. Arthi TS, Mathuravalli K, Jagadish R and Padmanaban V (Postgraduates, Department of Biochemistry); Joshua Martin, Rakshana MJ, and Praiselin Petrishya Joseph (MBBS students, Batch of 2014). Their inputs and contributions are duly acknowledged. MBBS students from Batch of 2015 are thanked for taking part in the study. The investigator would also like to acknowledge Dr. Tripti Jacob (Associate Professor, Department of Anatomy) for her critical comments on the manuscript.

Funding

No financial support was received for the study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

About the investigators

Anand R, MBBS, MD., is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biochemistry at Christian Medical College, Vellore. He is formally trained with experience in biochemistry and basic medical education, but not in qualitative research or podcasting.

Prakash SS, MBBS, MD., and Muthuraman N, MBBS, MD., are currently Assistant Professors in the Department of Biochemistry at Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR designed and conducted the study, created podcasts, collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. SSP and MN analyzed the qualitative data and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board, Christian Medical College, Vellore approved the study protocol (IRB Min. No. 10131 [OBSERVE] dated 22nd June 2016). All study participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Part B – Questionnaire. (DOCX 23 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Students' responses to question A1. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Students' responses to question A2. (DOCX 17 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S3.

Data from responses for items B3-B10. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S4.

List of assessment topics. (DOCX 12 kb)

Additional file 6: Table S5.

Average scores of 3MTL heavy users in assessments. (DOCX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Prakash, S., Muthuraman, N. & Anand, R. Short-duration podcasts as a supplementary learning tool: perceptions of medical students and impact on assessment performance. BMC Med Educ 17, 167 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1001-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1001-5