Abstract

Background

There are no published studies regarding the efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for the prevention of osteoporotic fracture. Therefore, we conducted this nationwide, population-based cohort study to investigate the probable effect of TCM to decrease the fracture rate.

Methods

We identified cases with osteoporosis and selected a comparison group that was frequency-matched according to sex, age (per 5 years), diagnosis year of osteoporosis, and index year. The difference between the two groups in the development of fracture was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test.

Results

After inserting age, gender, urbanization level, and comorbidities into the Cox’s proportional hazard model, patients who used TCM had a lower hazard ratio (HR) of fracture (adjusted HR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.37–0.59) compared to the non-TCM user group. The Kaplan-Meier curves showed that osteoporosis patients who used TCM had a lower incidence of fracture events than those who did not (p < 0.00001). Our study also demonstrated that the longer the TCM use, the lesser the fracture rate.

Conclusion

Our study showed that TCM might have a positive impact on the prevention of osteoporotic fracture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoporosis is defined as a skeletal disorder that occurs with the decrease in bone density and quality, leading to an increased risk of fracture [1]. The most frequent fracture areas are the hip, wrist, and spine. In the United States, 1.5 million osteoporotic patients over 50 years of age suffer from hip fractures each year [2] and over 3.5 million fragility fractures occur each year in Europe [3]. Osteoporotic fracture is an economic burden which cost US$17 billion annually in the United States in 2005 and €37 billion in Europe in 2010 [3, 4]. In Taiwan, the incidence of hip fracture increases 9.3% annually, with 13,892 women and 8616 men over 50 years of age suffering from hip fracture in 2010. According to the data from Health Promotion Administration, approximately 40% of women over the age of 70 need long-term bed rest and care due to hip fracture, and 10% die from hip fracture in Taiwan. In Taiwan, every case requires more than NT$100,000 during the acute phase, and more resources are needed in the long run [5]. The incidence of fractures is expected to increase over the next 30 years because of the increase in the aged population [6]. Half of all hip fractures will occur in Asia by 2050 where the amount of older people will be most markedly increased [7].

There are numerous drugs available for treating osteoporosis; however, only bisphosphonates and denosumab have been demonstrated to have antifracture efficacy. Besides, only teriparatide and intact Parathyroid hormone (PTH) are approved to stimulate bone formation; the others are antiresorptive agents. In view of this, people might wonder whether other therapies have been ignored. There are no published studies regarding the efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for the prevention of osteoporotic fracture. Some studies revealed the effects of TCM, such as Cistanche deserticola extract, Baicalin, Semen Astragali Complanati decoction, and Rhizoma Cibotii decoction, in regard to promoting bone formation, mineralization, and decreasing bone loss [8,9,10]. However, these studies used cell-lines and animal models. Therefore, large-scale, population-based analyses examining the preventative effect of TCM herbal products for osteoporotic fracture are needed.

To investigate the probable effect of TCM to decrease the fracture rate in patients with osteoporosis, we analyzed the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan from 2000 to 2010. TCM has been reimbursed by the National Health Insurance (NHI) program since 1996 in Taiwan, including Chinese herbal products, acupuncture/moxibustion, and manipulative therapy [11]. At the end of 2011, more than 99% of the population were enrolled in the NHI program [12]. This study provides important information for clinicians and shows that Chinese herbal prescriptions could also be useful for further pharmacological investigation or clinical trials.

Methods

Data source

Taiwan launched the mandatory National Health Insurance (NHI) program in 1995 and has been reimbursing Western and TCM since 1996. TCM treatment includes Chinese herbal medicine, acupuncture, and moxibustion therapy in ambulatory clinics. Large computerized data (NHIRD) was used to perform our nationwide population-based cohort study. We used the LHID2000 (Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000) provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, which is managed by the National Health Research Institutes. The LHID2000 includes data from 1 million randomly selected patients who were NHI beneficiaries in 2000. Similar distributions of beneficiaries based on age and gender of beneficiary age and gender in the LHID2000 and the general NHI database were observed. The registration and claim dataset from the LHID2000 spans the years 2000 to 2011. Ambulatory care claims contain an individual’s gender, date of birth, visit date, and the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for three primary diagnoses. Inpatient claims contain ICD-9-CM codes for the principal diagnosis and up to four secondary diagnoses. A disease diagnosis without valid supporting clinical findings may be considered as medical fraud by the NHI with a penalty of 100-fold the payment claimed by the treating physician or hospital. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of China Medical University (CMUH104-REC2–115).

Study population

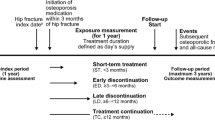

Our population cohort study used newly diagnosed osteoporosis patients (aged ≥18 years) identified between 2000 and 2010 and followed up until the December 31, 2011 or the first manifestation of fracture. Subjects with osteoporosis were required to have at least two outpatient claims or at least one inpatient claim with the diagnosis of ICD—CM code 733.0 during the study period. The exclusion criteria included less than 18 years old, incomplete information of age and sex, and withdrawal from the NHIRD during the follow-up period. Patients who received TCM treatment for their osteoporosis from the initial diagnosis to December 31, 2010, were identified as the TCM user cohort. The date of the first TCM treatment after a new diagnosis of osteoporosis was used as the index date for the cohort group. No diagnosis and TCM treatment code in the database was categorized as non-TCM users. Figure 1 shows the subject recruitment flowchart of osteoporosis patients from the NHIRD in Taiwan.

The recruitment flowchart of subjects from the one million samples randomly selected from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan. There were a total of 54,075 osteoporosis patients registered in the NHIRD, with 37,960 patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2010. After ruling out patients with missing information and aged > 18 years, as well as matching 1:1 by sex, age, diagnosis year of osteoporosis, and index year, both groups contained 804 patients

Covariate assessment

Sociodemographic factors included age and sex. Patients were divided into two groups based on their age; < 65 years and ≥ 65 years old. The townships in which subjects registered for insurance were grouped into four levels of urbanization based on a score calculated by incorporating variables indicating population density (people/km2), population ratio of different educational levels, population ratio of elderly, population ratio of agriculture workers, and the number of physicians per 100,000 people [13]. Baseline comorbidities comprised alcohol-related disease (ICD-9-CM: 291, 303, 305.00, 305.01, 305.02, 305.03, 571.0–571.3, 790.3, V11.3), cancer (140–208), cardiovascular disease (410–414, 428, 430–438, 440–448), chronic kidney disease (585–586, 588.8–588.9), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (491, 492, 493, 496), diabetes mellitus (250), dementia (290.0, 290.1, 290.2, 290.3, 290.4, 294.1, 331.0), depression (296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311), hyperlipidemia (272.0, 272.1, 272.2, 272.3, 272.4), hypertension (401–405), and Parkinson’s disease (332.x).

Data analysis

Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages. The difference in proportions was assessed using the chi-square test. Cox’s proportional hazard model estimated hazard ratios (HR) of TCM usage on fractures. The difference in fracture development between the two groups was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed and figures were created using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.) and R software, with p < 0.05 in two-tailed tests indicating statistical significance.

Results

Overall, there were 1427 TCM users and 3067 non-TCM users among the osteoporosis patients. After frequency matching, there were 804 patients in the TCM user and non-TCM user groups. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics according to TCM usage. Osteoporosis patients in both groups had a similar distribution of gender and age. The mean age of the TCM user and non-TCM user groups was 64.48 ± 11.08 and 64.57 ± 11.08, respectively, and the female and male percentages were 76.49 and 23.51%, respectively. Compared with non-TCM user group, TCM users had a higher proportion of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hyperlipidemia, but had a lower proportion of cancer.

A total of 323 patients were newly diagnosed with a fracture during the follow-up period (59% non-TCM users and 40% TCM users). A reduced risk of fracture recurrence was associated with TCM use (Crude HR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.4–0.63). After inserting age, gender, urbanization level, alcohol-related disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, dementia, depression, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and Parkinson’s disease into the Cox’s proportional hazard model, TCM use had a lower HR of fracture (adjusted HR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.37–0.59) compared to the non-TCM user group (Table 2).

The Kaplan-Meier curves showed that osteoporosis patients using TCM had a lower incidence rate of fracture events than those not using it (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2).

Table 3 shows the distribution of TCM users according to their accumulated days of herbal use. Patients with < 30 days of Chinese herb medicine use per year (including non-TCM users) were selected as the reference. Patients who accumulated between 30 and 180 days of herbal use showed an aHR of 0.60 (95% CI: 0.43–0.84), and those with more than 180 days of herbal use showed an aHR of 0.37 (0.20–0.68). When analyzing patients with more than 30 accumulated days of herbal use, those who cumulatively used herbal prescriptions for more than 180 days had a lower risk of fracture (aHR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.32–1.24) than in the compared cohort; however, this was not statistically significant.

The HR of the 10-single herb and multiherb products most commonly prescribed for the treatment of osteoporosis are listed in Table 4. Frequency meant how many times the single herb or multiple herb formula was used during the research. Number of person-days meant how many days the single herb or multiple herb formula was used during the research.

Discussion

With the increase in osteoporosis prevalence and incidence, prevention of osteoporotic fracture is of great importance [14]. People have become more interested in natural products in recent years and TCM is becoming a common choice in complementary and alternative medicine. There are some difficulties when surveying the preventive effect of TCM for osteoporotic fracture in operational studies. First, a long follow-up time is required for bone mass and fracture events. The longest reported follow-up time in Western medicine for osteoporosis was ten years [15]. Therefore, most studies focus on the benefit to bone health [16] rather than the fracture rate. Secondly, a common problem of studying TCM is that it is difficult to quantify Chinese herbs. Current Chinese herb studies focus on extracts or simple herbs [9, 17, 18], which greatly differ from those used in the clinical setting. For the above reasons, there are no studies on the fracture incidence following TCM therapy in patients with osteoporosis. Therefore, we could conduct this survey using NHIRD analysis.

Our results showed a decreased risk of fracture following the use of TCM therapy among osteoporosis patients (HR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.37–0.59; p < 0.0001). The follow-up period was also longer in the TCM user group than in the non-TCM user group (5.38 and 3.75 years, respectively). It means TCM use might delayed the occurrence of fracture after osteoporosis was diagnosed. The Kaplan–Meier curve also demonstrated that patients who took TCM had a lower incidence of fracture. In addition, our study demonstrated that the longer the use of TCM, the lesser the fracture rate. Patients who took TCM between 30 to 180 days were at less risk than those who took TCM for less than 30 days. Similarly, patients who took TCM for more than 180 days were at less risk than those who took TCM between 30 to 180 days. This result strengthens the relationship between TCM and osteoporotic fracture.

We should consider the possibility of a decreased fracture rate after using TCM therapy. First, TCM may improve bone strength [16], while falls are also a prominent factor for which one tenth lead to fracture [19]. Some studies demonstrate that the most important cause of a fracture is a fall rather than bone strength [20,21,22]. TCM may improve the quality of life by reducing limb pain or strengthening muscle endurance [23,24,25]. Some Chinese herbal clinical trials conducted in China showed that people who took Chinese herbs had a better quality of life or reduced symptoms including pain, muscle fatigue, and limited mobility. While these trials were included in a review study [26], they did not match the standard of peer-reviewed journals.

The frequency of major osteoporotic fractures varies in different races, especially in hip fractures, with rates varying by > 200-fold. White women have a higher fracture risk than black women. Furthermore, variation was also observed in different regions with northern Europe and Mediterranean areas experience the highest rates and the lowest rates, respectively [27]. Based on these differences, it is difficult to conclude the benefit of TCM when comparing ethnic groups.

The most commonly prescribed single herbs and formulas were presented in Table 4. While this is not the discussion point of our research, it may be important for clinicians and researchers. The results provide future research candidates for basic and clinical trials. Some herbs have been proven to be beneficial to bone health, such as Eucommiae Cortex (Du-Zhong) [28], Achuranthes (Huai-niu-xi) [29, 30], Salviae miltiorrhizae Radix [18], Dipsaci Radix (Xu-Duan) [31], Testudinis Plastrum (Gui-ban) [32,33,34], Drynariae Rhizoma (Gu sui-bu) [35,36,37], Du Huo Ji Sheng Tang [38], and zuo Gui Wan [39]. We found patients lived in highly urbanized areas were more likely to receive TCM treatment. In addition, some comorbidities showed significant difference between two groups in baseline. It might mean the patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hyperlipidemia preferred to receive TCM, and the patients with cancer were not disposed to use TCM. Besides, less cancer rate might also mean patients in TCM group take care themselves better than another group usually. Because of this, they go further to seek TCM treatment when osteoporosis is diagnosed.

There are some limitations to our research. Firstly, we were unable to include medicines taken at the patient’s own expense. According to the specification of the NHI program, Western medicine for osteoporosis can only be applied after a fracture occurred. It is possible that the patients source such medicines at their own expense when they were diagnosed with osteoporosis before a fracture happens. Secondly, some data related to fractures, such as a patient’s exercise, lifestyle, BMI, alcohol, and cigarette use is not available from the NHI program. Thirdly, the Kaplan–Meier curve might be influenced by economic levels and patient severity. However, we can conclude that TCM might have a positive impact on the prevention of osteoporotic fracture from Tables 2 and 3. Moreover, this study is derived from a very large, well-indicated data set, which provided a practical method to investigate the effect of TCM in osteoporotic patients. Our study not only reveals the preventative value of TCM use for patients with osteoporosis in the clinical setting, but also provides valuable information regarding the most common prescriptions provided to osteoporotic patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study had a relatively large population and long follow-up time, which demonstrated that TCM might have a positive impact on the prevention of osteoporotic fracture. Further research is needed to verify the causal relationship between TCM and the outcomes. More clinical trials are also required to confirm whether this relationship is true in non-Asian patients.

Abbreviations

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- LHID2000:

-

Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000

- NHI:

-

National Health Insurance

- NHIRD:

-

National Health Insurance Research Database

- PTH:

-

Parathyroid hormone

- TCM:

-

Traditional Chinese medicine

References

NCD P. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;6:285–785.

(US) OotSG. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. In: Reports of the Surgeon General. edn. Edited by Rockville; 2004.

Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jönsson B, Kanis JA. K: Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8(136).

Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465–75.

2015 Taiwan consensus guidelines and prevention of osteoporosis in adults. https://www.puzih.mohw.gov.tw/public/hygiene/ebf03aeee1551307ea349553c0726840.pdf.

Kinsella K, He W: U.S. Census Bureau, International Population Reports, P95/09–1. An Aging World: 2008, US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 2009.

Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ. Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int. 1992;2:285–9.

Li TM, Huang HC, Su CM, Ho TY, Wu CM, Chen WC, Fong YC, Tang CH. Cistanche deserticola extract increases bone formation in osteoblasts. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64(6):897–907.

Guo AJ, Choi RC, Cheung AW, Chen VP, Xu SL, Dong TT, Chen JJ, Tsim KW. Baicalin, a flavone, induces the differentiation of cultured osteoblasts: an action via the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(32):27882–93.

GGX ML, Rong P, Dong J, Zhang Z, Zhao H, Teng J, Zhao H, Pan J, Li Y, Zha Q, Zhang Y, Ju D. Semen astragali complanati- and rhizoma cibotii-enhanced bone formation in osteoporosis rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(141).

TP H, PH L, AS L, SL Y, HH C, Yen HR. Y: A nationwide population-based study of traditional Chinese medicine usage in children in Taiwan. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(3):500–10.

2011 National Health Insurance Annual Statistical Report [http://www.mohw.gov.tw/en/Ministry/Statistic.aspx?f_list_no=474&fod_list_no=5236]. Accessed 25 Jan 2019

Liu CYHY, Chuang YL, Chen YJ, Weng WS, Liu JS, Liang KY. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manag. 2006;14:1–22.

International Osteoporosis Foundation. https://www.iofbonehealth.org/impact-osteoporosis. Accessed 25 Jan 2019

Black DM, AVS KEE, Cauley JA, Levis S, Quandt SA, Satterfield S, Wallace RB, Bauer DC, Palermo L, Wehren LE, Lombardi A, Santora AC, Cummings SR. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment. JAMA. 2006;296(24).

Che CT, Wong MS, Lam CW. Natural products from Chinese medicines with potential benefits to bone health. Molecules. 2016;21(3):239.

Feng XLY, Wu Z, Fang Y, Xu H, Zhao P, Xu Y, Feng H. Fructus ligustri lucidi ethanol extract improves bone mineral density and properties through modulating calcium absorption-related gene expression in kidney and duodenum of growing rats. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;94(4):433–41.

Guo YLY, Xue L, Severino RP, Gao S, Niu J, Qin LP, Zhang D, Bromme D. Salvia miltiorrhiza: an ancient Chinese herbal medicine as a source for anti- osteoporotic drugs. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155(3):1401–16.

Berry SD, Miller RR. Falls: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and relationship to fracture. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6(4):149–54.

Kannus PU-RK, Palvanen M, Parkkari J. Non-pharmacological means to prevent fractures among older adults. Ann Med. 2005;37:302–10.

Svenhjalmar van Helden ACMvG, Piet P. Geusens, Alfons Kessels, Arie C. Nieuwenhuijzen Kruseman, Peter R.G. Brink: Bone and fall-related fracture risks in women and men with a recent clinical fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008, 90(241–248).

Jä r TLSH, Khan KM, Heinonen A, Kannus P. Shifting the focus in fracture prevention from osteoporosis to falls. BMJ. 2008;336:124–6.

Chen BZH, Marszalek J, Chung M, Lin X, Zhang M, Pang J, Wang C. Traditional Chinese medications for knee osteoarthritis pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Chin Med. 2016;44(4):677–703.

Chen BZH, Chung M, Lin X, Zhang M, Pang J, Wang C. Chinese herbal Bath therapy for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015.

Yeh TSHC, Chuang HL, Hsu MC. Angelica sinensis improves exercise performance and protects against physical fatigue in trained mice. Molecules. 2014;19(4):3926–39.

Liu Y, Liu JP, Xia Y. Chinese herbal medicines for treating osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD005467.

Johnell OGB, Allander E, Kanis JA. The apparent incidence of hip fracture in Europe: a study of national register sources. Osteoporos Int. 1992;2:298–302.

Qi S, Zheng H, Chen C, Jiang H. Du-Zhong (Eucommia ulmoides Oliv.) cortex extract alleviates Lead acetate-induced bone loss in rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2018.

Zhang SZQ, Zhang D, Wang C, Yan C. Anti-osteoporosis activity of a novel Achyranthes bidentata polysaccharide via stimulating bone formation. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;184:288–98.

D S, Z C, S H, J T, N L, H Q, X C, C W, K C, Y S, et al. Achyranthes bidentata polysaccharide suppresses osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption via inhibiting RANKL signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(6):4826–35.

K K, Q L, X Y, Z X, Y W, J S, L C, W X, L H, H S: Asperosaponin VI promotes bone marrow stromal cell osteogenic differentiation through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in an osteoporosis model. Sci Rep 2016, 19(6):35233.

GY S, H R, JJ H, ZD Z, WH Z, X Y, Q S, T Q, YZ Z, JJ T, et al. Plastrum Testudinis extracts promote BMSC proliferation and osteogenic differentiation by regulating let-7f-5p and the TNFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;47(6):2307–18.

H R, G S, J T, T Q, Z Z, W Z, X Y, J H, Liang ZY, et al. Promotion effect of extracts from plastrum testudinis on alendronate against glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in rat spine. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10617.

D L, H R, T Q, G S, B X, Q W, Z Y, J T, Z Z, X J: Extracts from plastrum testudinis reverse glucocorticoid-induced spinal. Biomed Pharmacother 2016, 82:151–160.

S S, Z G, X L, Y N, Y Z, C L, Y L, Z W. Total flavonoids of Drynariae Rhizoma prevent bone loss induced by Hindlimb unloading in rats. Molecules. 2017;22(7).

SH S, YK Z, CQ L, Q Y, Y L, Y Z, WP H, ZZ W. Effects of total flavonoids from Drynariae Rhizoma prevent bone loss in vivo and in vitro. Bone Rep. 2016;10(5):262–73.

ZC Q, XL D, Y D GKX, XL W, KC W, MS W, XS Y. Discovery of a new class of Cathepsin K inhibitors in Rhizoma Drynariae as potential candidates for the treatment of osteoporosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(12).

JY W, WM C, CS W, SC H, PW C, JH C. Du-Huo-Ji-sheng-Tang and its active component Ligusticum chuanxiong promote osteogenic differentiation and decrease the aging process of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;198:64–72.

N L, Z Z, B W, X M, Y G, C Y, Z W, L W, R M, X L, et al. Regulatory effect of traditional Chinese medicinal formula Zuo-Gui-wan on the. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;166:228–39.

NHIRD [ http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/]. Accessed 25 Jan 2019

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Uni-edit for editing and proofreading this manuscript.

Funding

The data analysis of this study is supported by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center (MOHW106-TDU-B-212-113004), China Medical University Hospital, Academia Sinica Taiwan Biobank Stroke Biosignature Project (BM10601010036), Taiwan Clinical Trial Consortium for Stroke (MOST 106–2321-B-039-005), Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan, Taiwan Brain Disease Foundation, Taipei, Taiwan, and Katsuzo and Kiyo Aoshima Memorial Funds, Japan.

Availability of data and materials

Large computerized data (NHIRD; [40]) was used to perform our nationwide population-based cohort study. We used the LHID2000 (Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000) provided by the National Health Insurance Administration, which is managed by the National Health Research Institutes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantive intellectual contributions to this study to qualify as authors. YCW and CHT designed the study. YCW and CHT collected subject data. JHC performed statistical analysis. An initial draft of the manuscript was written by YCW. JHC, HCH, and CHT re-drafted parts of the manuscript and provided helpful advice on the final revision. All authors were involved in writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, YC., Chiang, JH., Hsu, HC. et al. Decreased fracture incidence with traditional Chinese medicine therapy in patients with osteoporosis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BMC Complement Altern Med 19, 42 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2446-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2446-3