Abstract

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is major public health problem that affects many dimensions of women’s health. However, the role of IPV on women’s reproductive health in general and pregnancy loss in particular, is largely unknown in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study investigated the association between IPV and pregnancy loss in Ethiopia.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of nationally representative data from the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) was conducted. Married women of reproductive age (15–49 years) who participated in the domestic violence sub-study of the survey were included in the analysis. Adjusted odds ratios were estimated using multilevel logistic regression models to represent the association of IPV with outcome variable.

Results

Among 4167 women included in the analysis, pregnancy loss had been experienced by 467 (11.2%). In total, 1504 (36.1%) participants reported having ever experienced any form of IPV, with 25.1, 11.9, and 24.1% reporting physical, sexual and emotional IPV respectively. A total of 2371 (56.9%) women had also experienced at least one act of partner controlling behaviour. After adjusting for potential confounders, a significant association was observed between IPV (a composite measure of physical, sexual and emotional abuse) and pregnancy loss (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) 1.54, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.12, 2.14). The odds of pregnancy loss were also higher (AOR 1.72, 95% CI: 1.06, 2.79) among women who had experienced multiple acts of partner controlling behaviours, compared with women who had not experienced partner controlling behaviours. The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) indicated that pregnancy loss exhibits significant between-cluster variation (p < 0.001); about 25% of the variation in pregnancy loss was attributable to differences between clusters.

Conclusion

IPV against women, including partner controlling behaviour, is significantly associated with pregnancy loss in Ethiopia. Therefore, there is a clear need to develop IPV prevention strategies and to incorporate IPV interventions into maternal health programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The aim of the current study is to examine pregnancy loss in relation to intimate partner violence (IPV) including partner controlling behaviours in Ethiopia. Pregnancy loss and IPV are both high in Ethiopia, but there is a lack of evidence regarding the relationship between the two major public health problems in the country. IPV is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “any behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship that includes acts of physical aggression, psychological abuse, sexual coercion and controlling behaviours” ([1] p89). For the purposes of this paper, pregnancy loss is defined as the termination of pregnancy either through abortion or stillbirth [2, 3]. Abortion is defined as the termination of pregnancy before foetal viability. Abortion can be either spontaneous (miscarriage), which is the termination of a pregnancy not provoked deliberately, or induced, which is voluntary termination of pregnancy [4]. Induced abortion is unsafe if it is performed in an unhygienic setting, by unqualified providers or without the necessary equipment [4]. Worldwide, the estimated annual number of unsafe abortions between 2010 and 2014 was 25.1 million, representing 45% of all abortions globally, and 97% of abortions in developing countries [5]. In Ethiopia, in 2014, it was estimated that 13% of all pregnancies ended with induced abortion [6]. Moreover, many women had unsafe abortions with about 47% of abortions not performed in a health facility [6]. Unsafe induced abortion is one of the five leading direct causes of maternal mortality in Ethiopia [7]. In addition to their effect on maternal mortality, abortions also contribute to other long-term adverse maternal health consequences, such as chronic pain, pelvic inflammatory diseases, ectopic pregnancies, infertility, and mental health problems [8].

Different socio-economic, demographic and fertility-related factors have been found to be associated with abortion. Factors commonly related to abortion are younger maternal age, unstable relationships, rape, family objection to the pregnancy, health concerns, non-use of contraception, contraceptive failure, lack of reproductive education, limited access to reproductive health services, and financial constraints [8,9,10]. IPV, which is also a global public health problem and affects one in every three women [11], has been identified as a factor associated with induced abortion [12, 13] and spontaneous abortion [14, 15]. However, there are some limitations in estimating the effect of IPV on abortion. For instance, it is more difficult for women to disclose induced abortion, especially if the abortion was illegal [16] or culturally unacceptable, [8] which might lead to bias. Additionally, there is no universal definition of abortion; for example, some countries define abortion as occurring before 20 weeks of gestation [15] or 22 weeks of gestation [17], while others use a 28 week threshold [14]. For this reason, women may also face difficulties identifying the technical distinction between miscarriage (involuntary termination of pregnancy before viability of foetus to survive out of the uterus) and stillbirth (involuntary termination after viability) [8, 18]. Due to this, some researchers have classified these outcomes as a composite measure using the term “pregnancy loss” [2, 3, 13, 19,20,21]. In studies conducted based on these composite measures, researchers have found a significant relationship between maternal IPV experience and pregnancy loss [2, 3, 13, 16, 19,20,21,22]. In communities with patriarchal norms, partner controlling behaviour may also affect women’s decision-making regarding fertility and use of contraception, which could also contribute to termination of pregnancy [22,23,24].

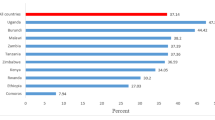

Ethiopia has one of the highest national rates of IPV, with the lifetime prevalence of IPV ranging from 20 to 78% in different areas of the country [25] and about 57% of women reporting having experienced at least one form of marital controlling behaviour from their partner [7]. There are no consolidated IPV prevention guidelines or services in the Ethiopian health system. Existing interventions are mainly for rape victims. Tolerant community norms with regard to IPV can lead individuals and organisations to disregard some acts of violence; norms of male superiority, and perceiving IPV as an inevitable part of a relationship allow IPV to persist in Ethiopian society and challenge intervention and prevention efforts [26]. In such contexts, a violent and/or controlling partner can further escalate the rate of abortion. In one small-scale study from west Ethiopia, significant relationship between women’s experience of IPV and termination of pregnancy (spontaneous/induced abortion) were identified [27]. However, there is no sufficient national level evidence regarding the role of IPV in pregnancy loss in Ethiopia.

The existing evidence regarding the effects of IPV on women’s health in Ethiopia is also limited. Existing studies have found associations between IPV and depression [28,29,30,31], psychiatric disorders [32], risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections [27] and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) [33, 34], unmet need for family planning [35], unintended pregnancy [27], and low maternal health service utilization [36, 37]. Most of the studies have been conducted in small geographic locations that lack national level representativeness. Insufficient national level evidence might be one of the reasons that little attention has been given to IPV within maternal health programs. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the association of IPV, including partner controlling behaviour, with pregnancy loss in Ethiopia.

Methods

Data source

This study used data from the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), which was the year the domestic violence module was added. The EDHS was a national survey conducted from 18 January to 27 June 2016. The 2016 EDHS data was collected with five questionnaires (household, women, men, biomarker and health facility).

Sample size and sampling procedures

The EDHS used 84,915 enumeration areas; each enumeration area has an average of 181 households from nine regions and two city administrations. A two-stage stratified cluster sampling design was then implemented. First, 645 enumeration areas were selected from urban (202 enumeration areas) and rural (443 enumeration areas) areas based on proportional to size allocation. In the second stage, on average, 28 households per selected enumeration area were identified using systematic random sampling. All women aged 15–49 years in the household were eligible for the EDHS interview. Accordingly, 15,683 women, with a response rate of 95%, participated in the general survey [7].

For the domestic violence sub-study, only one married woman per household was interviewed. Of those women who were eligible, 97% (n = 5860) were interviewed, with 3% not involved mainly due to a lack of privacy. Background characteristics between selected women for the IPV sub-study and the general female population in the selected households was shown to be similar and did not reduce representativeness of the EDHS sample [7].

For this analysis, ever-married women who had complete data related to their pregnancy and birth history and responded to the IPV questionnaire were included. Women who had never been pregnant, who were missing either the outcome variable or IPV data were excluded from the analysis. Accordingly, 4167 (unweighted sample of 4372) women were included in the analysis.

Measurement and variables

The outcome variable for this study was pregnancy loss. In the 2016 EDHS, women were asked a single question “Did you have any miscarriages, abortions or stillbirths that ended before 2011?” In addition, women were asked about their pregnancy and birth history during the 5 years (2011 to 2016) before the survey that provided information about whether the pregnancy was terminated or ended with a live birth [7]. Aggregating the responses from these two questions, women who had ever experienced pregnancy loss were identified. Accordingly, pregnancy loss was coded as ‘Yes’ if respondents reported ever having experienced a miscarriage, induced abortion, or stillbirth and ‘No’ if women had never experienced any of the three events. This method of defining pregnancy loss has been used in previous research [18, 20, 22].

The exposure variable was having ever experienced IPV (physical, emotional, and sexual violence, and partner controlling behaviour). IPV was measured based on women’s self-reported responses to questions asked whether or not they had experienced a number of violent acts within their relationship, perpetrated by their husband/partner for currently married women and recent husband/partner for previously married women (including widows). Physical IPV was assessed by asking participants seven questions regarding having: ever been pushed, shaken, or thrown something at her; slapped; her arm twisted or hair pulled; punched with fist or with something that could hurt; kicked, dragged, or beaten up; been choked or burnt on purpose; or been threatened or attacked with a knife, gun, or any other weapon. Three questions were asked to measure sexual IPV: having ever been physically forced to have sexual intercourse with her partner even when she did not want to, physically forced to perform any other sexual acts she did not want to, or forced with threats or in any other way to perform sexual acts she did not want to. Likewise, emotional IPV was assessed by asking three questions: if the participant had ever been humiliated, threatened, or insulted or made to feel bad about herself. Those women who were married more than once were also asked about spousal violence committed by any other husband/partner with two questions that asked about having ever been hit, slapped, kicked or done something else to hurt her and ever been physically forced to have intercourse or perform any other sexual acts against her will. Respondents were categorized as having experienced lifetime IPV if they had experience of any single act of physical, sexual or emotional IPV since the age of 15 years [7]. Likewise, any single act of partner controlling behaviour was categorized as ‘yes’ if one of the following behaviours were reportedly carried out on a woman by her husband: ‘being jealous if she talks to men’, ‘accusing her of being unfaithful’, ‘does not allow her to meet her friends’, ‘limits her contact with family’, and ‘tries to know where she is at all times’. Where women reported two or more acts of partner controlling behaviour, the responses were coded as ‘multiple controlling behaviours’ [7].

Variables that needed to be controlled in order to estimate the unbiased effect of the exposure upon the outcome were identified based on an examination of previous literature [2, 3, 8, 13, 16, 18,19,20,21,22, 27]. Accordingly, current age of the respondent (15–19/20–24/25–29/30–34/35–39/40–44/45–49 years), age at first cohabitation (< 15/15–18/≥18 years), respondent’s educational status (uneducated/primary/secondary+), religion (Christian/Muslim/other), number of children ever born (≤1/2–3/≥4) were considered. In addition, respondent’s employment status, rurality (urban/rural), region (11 administrative regions), decision-making, wealth index, media access, substance abuse, and pregnancy intention were included. Respondent’s employment status was grouped as employed/not employed based on their response to “have you been employed in the last 12 months”. Decision-making autonomy was coded as ‘yes’ if women reported being involved in all decisions regarding her own health care, major household purchases and visits to her family or relatives. Household wealth index was measured based on the number and kind of goods households have and housing characteristics (drinking water, toilet facility, flooring material and availability of electricity), and was generated using principal component analysis and classified into quintiles from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very rich). Media access was measured as whether the respondent read a newspaper, listened to the radio, or watched television and was categorized as no access, access less than once a week, and access at least once a week. Substance abuse was classified ‘yes’ if respondent drinks alcohol, chews khat (a green plant consumed as a stimulant) or smokes tobacco and ‘no’ otherwise. Pregnancy intention of respondents was categorized into two as ‘unintended’ and ‘intended’. A respondent was defined as having an unintended pregnancy if she had a pregnancy in the past 5 years that was either mistimed (wanted the pregnancy to happen later i.e. after 2 years) or unwanted (did not want the pregnancy at all).

Data processing and analysis

Multilevel logistic regression models were fitted considering hierarchical nature of EDHS data (4167 women nested in 640 clusters). Multilevel analysis allows for the estimation of valid standard errors by adjusting for within-cluster correlation of the response variable [38]. Two models were constructed; Model I (the empty or unconditional model) and Model II (two independent models for IPV and partner control behaviours). In Model I, no independent variables were included. This model was used to estimate the random intercept at cluster level and the variation in pregnancy loss between clusters. Then, a second model was constructed by adding covariates and main independent variable (IPV or partner controlling behaviours) to Model I. Interactions between variables were assessed. Model fit was tested using Likelihood ratio test and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Model II was the final model used to estimate measures of association between IPV and pregnancy loss. Adjusted odds ratios together with the 95% CI were used to report associations. Statistical significance was declared using a p-value < 0.05. The measure of variance (random effects) was reported in terms of the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). The ICC measures the extent to which women within the same cluster are more similar to each other in the outcome variable (i.e. pregnancy loss) than they are to women in different clusters [38].

All the analyses took into account the EDHS sampling weight and were based on the weighted sample (n = 4167). The sampling weights used in the EDHS account for the complex sampling procedures (multi-stage stratified cluster sampling) that might cause an unequal probability of selection for certain areas or subgroups either due to design or coincidence. Hence, sampling weights were adjusted for differences in probability of selection and interview that allow extrapolation of results to the national level of representativeness [7].

Results

General characteristics of respondents

The majority of study participants were aged 25–29 years (22.4%), married before 18 years of age (63.6%), illiterate (63.6%), Christian (65.2%) or living in a rural area (82.7%). In total, 39.1% of participants reported having no decision-making autonomy, 47.9% of individuals described themselves as having a habit of substance abuse, and 63.1% had no access to media. In terms of regional context, about two third of participants were from Oromia (n = 1659; 39.8%) and Amhara (n = 966; 23.2%) regions whereas three regions (Dire Dawa, Gambela, and Harari) represents only 1% of study participants (Table 1).

Prevalence of different forms of IPV and pregnancy loss

Table 2 shows the estimated prevalence of different forms of IPV and pregnancy loss with 95% CIs. The least prevalent form of IPV was sexual IPV (n = 496, 11.9%), and the most prevalent form was partner controlling behaviour (n = 2371, 56.9%). About two in every three women had experienced at least one form of IPV in their lifetime. The number of participants who had experienced pregnancy loss was 467 (11.2%). Table 3 shows pregnancy loss by different participant characteristics.

The association of IPV with pregnancy loss

In the univariate analysis, a significant association was observed between pregnancy loss and any form of IPV (Crude Odds Ratio (COR) 1.48; 95% CI 1.10, 2.00) and multiple acts of partner controlling behaviour (COR 1.45; 95% CI 1.02, 2.05). However, there were no significant associations observed between women experiencing single act of partner controlling behaviour and pregnancy loss (COR 1.39; 95% CI 0.95, 2.02) (Table 4).

The results of the multilevel logistic regression analyses are presented in Table 4. Model I shows that there was statistically significant variation in pregnancy loss between clusters (σ2 = 1.23, p-value < 0.001). The ICC showed that pregnancy loss within the same cluster had a higher clustering (ICC = 27.2%). After the inclusion of independent variables in Model II, the ICC indicated that about 25% of the variation in pregnancy loss was attributable to differences between clusters. In addition, after controlling for sociodemographic and fertility-related variables, significant associations were observed between experience of any form of IPV (AOR 1.54, 95% CI: 1.12, 2.14) and having experienced multiple acts of partner controlling behaviour (AOR 1.72, 95% CI: 1.06, 2.79) and pregnancy loss.

Discussion

The current study is based on nationally representative Ethiopian data and revealed that IPV was associated with pregnancy loss (abortion, miscarriage, or stillbirth) after controlling for potentially confounding variables. Multiple, but not single, partner controlling behaviours were also associated with pregnancy loss. This is the first national level study to investigate pregnancy loss in relation to IPV in Ethiopia. The results make evident that maternal health programs in Ethiopia must design strategies to reduce IPV and extend the existed maternal health services to encompass IPV services.

The findings of this study revealed that experience of IPV was associated with pregnancy loss. This finding is in line with results from studies performed in Germany [22], Pakistan [2], Bangladesh [13, 16], Cameroon [3], Democratic Republic of Congo [19], Tanzania [20], Kenya [21], and west Ethiopia [27]. Previous studies have also shown that IPV was significantly associated with induced abortion [12, 13, 20] and miscarriage [14, 15]. It is important to note that there may be reverse causality between IPV and pregnancy loss, in that women who have experienced pregnancy termination might experience IPV [24]. For example, a longitudinal study from India indicated that a history of induced abortion increased subsequent sexual and verbal abuse [24]. This might especially occur in communities where women are considered responsible for poor reproductive health outcomes [20].

The current study has also demonstrated that the odds of pregnancy loss were higher among women who have experienced multiple acts of partner controlling behaviour. This finding is in line with results from a study conducted in India [23]. Other previous studies have also established that partner’s reproductive coercion against wives, such as forced sexual activity, forced contraception, and forced pregnancy, result in a higher likelihood of termination of pregnancy [39,40,41]. However, the way partner controlling behaviour was measured in these studies was different to the measures used in the current study. We measured partner control in a way that reflects the general autonomy of women in their relationship whereas previous studies measured ‘partner control’ using measures of women’s sexual and reproduction autonomy [39, 40]. Hence, the findings are not directly comparable.

In the current study, there was no significant relationship between a single partner controlling behaviour and pregnancy loss. The higher the number of partner controlling behaviours, the more severely a woman was being controlled; therefore, her autonomy in decision-making is lower, and her ability to control her fertility is more likely to be compromised compared with women not subjected to controlling behaviours. This can lead to unintended pregnancies that in turn may further increase the rate of induced abortion [6, 10].

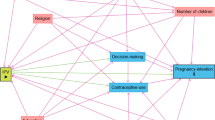

Different potential direct and indirect pathways can be proposed for the observed associations between IPV and partner controlling behaviour with pregnancy loss. The direct pathways operate through injury, such as blunt abdominal trauma that leads to miscarriage [15, 16, 22] and through Sexually Transmitted Diseases such as HIV that occur due to sexual violence [42, 43] that in turn lead to foetal infection and miscarriage [14]. In addition, the mother’s poor mental or physical health that occurs due to IPV can cause poor foetal health [44, 45]. Withholding access to maternal health care due to partner controlling behaviour [20, 46, 47], or unwanted pregnancies that occur as a result of the inability to make decisions about fertility [8, 48, 49] can also explain the observed associations. The schematic representation of the possible pathways from IPV to pregnancy loss are presented in Fig. 1. While these have been demonstrated in past research, many of these pathways have not yet been examined in the Ethiopian context. Future longitudinal research is needed to verify and clarify the causal and temporal pathways between IPV and pregnancy loss. The current study has laid a foundation for this future work.

According to the UN report in 2016, Ethiopia’s Gender Inequality Index (GII) was 0.499 (ranked 116th of 188 countries), which is much higher than the perfect gender equality marker of GII of zero [50]. Therefore, as this study was conducted in a country where there is high gender inequality and patriarchal views [50], with high fertility desire among men more so than among women [7], men may threaten their wives and restrict them from accessing abortion services [51]. Due to this, women may not disclose abortion to their partner. When women attempt to hide access of abortion services from their abusive partner, they may be at increased risk of unsafe abortion [20]. Moreover, some women may not have been able to terminate their pregnancy safely due to beliefs that safe abortion is expensive or unavailable [10].

The Sustainable Development Goals with the theme of ‘no one should left behind’ [52] also put emphasis on improving gender equality. It is difficult to achieve this goal unless the issue of IPV is well addressed in the national programs of the country. Therefore, the outcomes of this study might be useful in developing comprehensive IPV prevention strategies and incorporate IPV interventions into existing maternal health programs. IPV interventions that focus on prevention, provision and protection (3Ps) can be put in place. With regard to prevention, the health sector should integrate IPV screening tools in maternal health care services and identify women who are experiencing IPV. The health sector can also play active roles in creating awareness about the consequences of IPV through school-based programs, community conversations and media. Other key interventions include counselling, medical care, and shelters. Case reporting systems and referral pathways are also needed to facilitate provision of these services. Intersectoral collaborations between justice, social and health systems can bring about systemic changes that protect women from IPV and promote women’s overall health. We also suggest policymakers, health care providers and stakeholders working in tackling IPV against women can use the evidence of the current study to underscore the need for funding such endeavours.

Lastly, this study revealed that variation in pregnancy loss was not completely explained by the included variables. This shows that some other community level variables and arcane social processes might be present. Therefore, future studies should focus on investigating community level factors and explore the social processes contributing to pregnancy loss. This is principally helpful for countries like Ethiopia, which contains a population of over 80 ethnic groups living in diverse contexts. These findings also suggest combined interventions directed at different community groups and regions may help to reduce pregnancy loss in this country.

Strength and limitations of the study

The current study reveals the first Ethiopian national evidence that demonstrates the association between IPV and pregnancy loss, which is based on nationally representative and high quality data that were collected with well-trained data collectors, standardized measurement tools, and firm consideration of research ethics. This study has also provided new evidence that partner controlling behaviour, as a form of IPV, increases the odds of pregnancy loss. However, the study has limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of study precludes the analysis of cause and effect relationships, as previously mentioned. Similarly, since both the exposure (IPV) and outcome (pregnancy loss) variables were measured retrospectively, it is possible that the outcome preceded the exposure in some cases. Second, although potential confounding variables were included, there could still be some residual confounding effects. For example, some factors occurring during pregnancy such as foetal conditions, maternal nutrition and weight gain, and infections were not assessed in this study due to these variables not being recorded in the dataset. The ICC estimates also suggest that the included variables did not completely explained the variation in pregnancy loss. Third, women may not want to report their experience of pregnancy loss due to distress or social reasons and under-reporting of IPV may occur due to fear of repercussions, stigma, or shame. However, the study has strictly followed WHO strategies for domestic violence research, which minimizes such under-reporting. Lastly, in Ethiopia, where patriarchal views are common, controlling behaviour is considered an acceptable behaviour for husbands in interactions with their wives [53, 54]. For this reason, women might not consider some controlling behaviours to be controlling, and this might led to underreporting.

Conclusions

This study provides an important public health message that pregnancy loss is associated with IPV and partner controlling behaviour. The study also showed that significant cluster-level effects were found. The observed association makes evident that interventions are needed to reduce IPV in Ethiopia; this could help to minimize poor maternal health outcomes resulting from pregnancy loss.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is freely available to the public at www.measuredhs.com and can be accessed after request is made to and approved by the Demographic and Health Survey program.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COR:

-

Crude Odds Ratio

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- IPV:

-

Intimate Partner Violence

References

Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

Zakar R, Nasrullah M, Zakar MZ, Ali H. The association of intimate partner violence with unintended pregnancy and pregnancy loss in Pakistan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(1):26–31.

Alio AP, Nana PN, Salihu HM. Spousal violence and potentially preventable single and recurrent spontaneous fetal loss in an African setting: cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2009;373(9660):318–24.

Ganatra B, Tunçalp Ö, Johnston HB, Johnson BR Jr, Gülmezoglu AM, Temmerman M. From concept to measurement: operationalizing WHO’s definition of unsafe abortion. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(3):155.

Sedgh G, Bearak J, Singh S, Bankole A, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, et al. Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):258–67.

Moore AM, Gebrehiwot Y, Fetters T, Wado YD, Bankole A, Singh S, et al. The estimated incidence of induced abortion in Ethiopia, 2014: changes in the provision of services since 2008. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;42(3):111–20.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA). Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016 full report. Addis Ababa and Calverton: Central Statistical Agency (CSA); 2017.

Pallitto CC, Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Heise L, Ellsberg M, Watts C, et al. Intimate partner violence, abortion, and unintended pregnancy: results from the WHO multi-country study on Women's health and domestic violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;120(1):3–9.

Lauro D. Abortion and contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: how women plan their families. Afr J Reprod Health. 2011;15(1):13–23.

Gebreselassie H, Fetters T, Singh S, Abdella A, Gebrehiwot Y, Tesfaye S, et al. Caring for women with abortion complications in Ethiopia: National estimates and future implications. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;36(1):6–15.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and nonpartner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Taft AJ, Watson LF. Termination of pregnancy: associations with partner violence and other factors in a national cohort of young Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(2):135–42.

Rahman M. Intimate partner violence and termination of pregnancy: a cross-sectional study of married Bangladeshi women. Reprod Health. 2015;12:102.

Johri M, Morales RE, Boivin JF, Samayoa BE, Hoch JS, Grazioso CF, et al. Increased risk of miscarriage among women experiencing physical or sexual intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Guatemala City, Guatemala: cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:49.

Nur N. Association between domestic violence and miscarriage: a population-based cross-sectional study among women of childbearing ages, Sivas, Turkey. Women Health. 2014;54(5):425–38.

Silverman JG, Gupta J, Decker MR, Kapur N, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. BJOG. 2007;114(10):1246–52.

Nelson DB, Grisso JA, Joffe MM, Brensinger C, Ness RB, McMahon K, et al. Violence does not influence early pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(5):1205–11.

Rao N, Norris Turner A, Harrington B, Nampandeni P, Banda V, Norris A. Correlations between intimate partner violence and spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, and neonatal death in rural Malawi. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138(1):74–8.

Tiruneh FN, Chuang KY, Ntenda PAM, Chuang YC. Unwanted pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and other risk factors for intimate partner violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Women Health. 2018;58(9):983–1000.

Stockl H, Filippi V, Watts C, Mbwambo JK. Induced abortion, pregnancy loss and intimate partner violence in Tanzania: a population based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:12.

Emenike E, Lawoko S, Dalal K. Intimate partner violence and reproductive health of women in Kenya. Geneva: International Council of Nurses; 2008.

Stockl H, Hertlein L, Himsl I, Delius M, Hasbargen U, Friese K, et al. Intimate partner violence and its association with pregnancy loss and pregnancy planning. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(1):128–33.

Tiwari S, Gray R, Jenkinson C, Carson C. Association between spousal emotional abuse and reproductive outcomes of women in India: findings from cross-sectional analysis of the 2005-2006 National Family Health Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(5):509–19.

Stephenson R, Jadhav A, Winter A, Hindin M. Domestic violence and abortion among rural women in four Indian states. Violence Against Women. 2016;22(13):1642–58.

Semahegn A, Mengistie B. Domestic violence against women and associated factors in Ethiopia; systematic review. Reprod Health. 2015;12:78.

FDRE Ministry of Health (FMoH). Health sector gender mainstreaming manual. Addis Ababa: FDRE Ministry of Health (FMoH); 2013.

Abeya S, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Health effects of intimate partner violence against women: evidence from community based cross sectional study in Western Ethiopia. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2013;2:48.

Deyessa N, Berhane Y, Alem A, Ellsberg M, Emmelin M, Hogberg U, et al. Intimate partner violence and depression among women in rural Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health. 2009;5:8.

Adamu AF, Adinew YM. Domestic violence as a risk factor for postpartum depression among Ethiopian women: facility based study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2018;14:109.

Belay S, Astatkie A, Emmelin M, Hinderaker SG. Intimate partner violence and maternal depression during pregnancy: a community-based cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220003.

Woldetensay YK, Belachew T, Biesalski HK, Ghosh S, Lacruz ME, Scherbaum V, et al. The role of nutrition, intimate partner violence and social support in prenatal depressive symptoms in rural Ethiopia: community based birth cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):374.

Belete H. Leveling and abuse among patients with bipolar disorder at psychiatric outpatient departments in Ethiopia. Ann General Psychiatry. 2017;16:29.

Hassen F, Deyassa N. The relationship between sexual violence and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among women using voluntary counseling and testing services in south Wollo Zone, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:271.

Deyessa N. Intimate partner violence and Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection among married women in Addis Ababa. Ethiop Med J. 2018;56(1):51–9.

Deyessa N, Argaw A. Intimate partner violence and unmet need for contraceptive use among Ethiopian women living in marital union. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2018;32(3):1–8.

Mohammed BH, Johnston JM, Harwell JI, Yi H, Tsang KW, Haidar JA. Intimate partner violence and utilization of maternal health care services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):178.

Gashaw BT, Magnus JH, Schei B. Intimate partner violence and late entry into antenatal care in Ethiopia. Women Birth. 2019;32(6):e530–e7.

Peugh JL. A practical guide to multilevel modeling. J Sch Psychol. 2010;48(1):85–112.

Moore AM, Frowirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(11):1737–44.

Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Levenson RR, Waldman J, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence, and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–22.

John NA, Edmeades J. Reproductive coercion and contraceptive use in Ethiopia. Etude Popul Afr. 2018;32(1):3884–92.

Laanpere M, Ringmets I, Part K, Karro H. Intimate partner violence and sexual health outcomes: a population-based study among 16-44-year-old women in Estonia. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;23(4):688–93.

Lary H, Maman S, Katebalila M, McCauley AJM. Exploring the association between HIV and violence: young people’s experiences with infidelity, violence and forced sex in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30:200–6.

Morland LA, Leskin GA, Block CR, Campbell JC, Friedman MJ. Intimate partner violence and miscarriage: examination of the role of physical and psychological abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(5):652–69.

Al-Modallal H, Sowan AK, Hamaideh S, Peden AR, Al-Omari H, Al-Rawashdeh AB. Psychological outcomes of intimate partner violence experienced by Jordanian working women. Health Care Women Int. 2012;33(3):217–27.

Arcos E, Uarac M, Molina I, Repossi A, Ulloa M. Impact of domestic violence on reproductive and neonatal health. Rev Med Chil. 2001;129(12):1413–24.

Ibrahim ZM, Sayed Ahmed WA, El-Hamid SA, Hagras AM. Intimate partner violence among Egyptian pregnant women: incidence, risk factors, and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2015;42(2):212–9.

Sarkar NN. The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(3):266–71.

Nguyen PH, Nguyen SV, Nguyen MQ, Nguyen NT, Keithly SC, Mai LT, et al. The association and a potential pathway between gender-based violence and induced abortion in Thai Nguyen province, Vietnam. Glob Health Action. 2012;5:1–11.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human development report 2016. New York: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); 2016.

Kebede MT, Hilden PK, Middelthon A-L. The tale of the hearts: deciding on abortion in Ethiopia. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(4):393–405.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Sustainable development goals (SDGs). 2015.

Abeya SG, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Intimate partner violence against women in West Ethiopia: a qualitative study on attitudes, woman’s response, and suggested measures as perceived by community members. Reprod Health. 2012;9:14.

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–9.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the University of Newcastle, Australia which has provided a scholarship for the student researcher (Tenaw Yimer Tiruye) and Australian Research Council that has funded Dr. Melissa Harris. We are grateful to the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia and Measure Demographic and Health Survey program, which allowed us to access and use the data freely. We are also thankful to the women who participated in the survey and shared their IPV experiences. We thank the University of Newcastle, the Hunter Medical Research Institute, and the Research Centre for Generational Health and Ageing for creating a quality research environment for us to accomplish this work.

Funding

This study is partially funded by the University of Newcastle, Australia which has provided a scholarship for the student researcher (primary author) and supported him in obtaining statistical support and training. The third author is funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TYT carried out conceptualization of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the original draft. CC, MLH, EH and DL have made substantial contributions to the conception of the study, the analysis and interpretation of data. CC, MLH, EH and DL provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. All authors contributed to reviewing and editing the original draft and the final manuscript. The authors have read and approved the final manuscript and each author agrees with its submission.

Authors’ information

Tenaw Tiruye is a Ph.D. student at the University of Newcastle, Australia. His research focuses on the determinants, consequences and responses to intimate partner violence. He is interested in evaluating multidimensional effects of intimate partner violence on maternal and child health and generating evidence for decision-making. Prof Deb Loxton is a professor of public health at the University of Newcastle. She is a co-director of research center for generational health and aging and co-director of Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. She has interest on examining the health and wellbeing of women who have lived with violent partners, and the impact of reproductive health options and choices on women. Dr. Catherine Chojenta is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Newcastle. She is a public health researcher with a particular focus on women’s health and wellbeing across the life course. Dr. Melissa Harris is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Newcastle. Dr. Harris has an interest in chronic diseases management, including the impacts of psychological factors on physical health and healthcare outcomes and contraceptive practices of women. Dr. Liz Holliday is an Associate Professor and senior biostatistician in the School of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Newcastle. Her particular focus is promoting statistical excellence in medical research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The original survey was conducted after being ethically approved by the National Research Ethics Review Committee (NRERC) (Ref. No: 3.10/114/2016). EDHS questions follow World Health Organization (2001) ethical and safety precautions and strategies for domestic violence research. Accordingly, one woman per household was interviewed, and the interview continued only if participants consent to participate and privacy was certain. Confidentiality was completely assured, interviewers were well trained and all the necessary information was provided for women who had experienced IPV [7]. Before the analysis, permission from the Demographic and Health Survey program and ethical approval from University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref. No: H-2018-0055) was obtained.

Consent for publication

“Not applicable”.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist. All authors agreed on the submission of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiruye, T.Y., Chojenta, C., Harris, M.L. et al. Intimate partner violence against women and its association with pregnancy loss in Ethiopia: evidence from a national survey. BMC Women's Health 20, 192 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01028-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01028-z