Abstract

Background

Pancreatic cancer is noted for its late presentation at diagnosis, limited prognosis and physical and psychosocial symptom burden. This study examined associations between timing of palliative care referral (PCR) and aggressive cancer care received by pancreatic cancer patients in the last 30 days of life through a single health service.

Method

A retrospective cohort analysis of end-of-life (EOL) care outcomes of patients with pancreatic cancer who died between 2012 and 2016. Key indicators of aggressive cancer care in the last 30 days of life used were: ≥1 emergency department (ED) presentations, acute inpatient/intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and chemotherapy use. We examined time from PCR to death and place of death. Early and late PCR were defined as > 90 and ≤ 90 days before death respectively.

Results

Out of the 278 eligible deaths, 187 (67.3%) were categorized as receiving a late PCR and 91 (32.7%) an early PCR. The median time between referral and death was 48 days. Compared to those receiving early PCR, those with late PCR had: 18.1% (95% CI 6.8–29.4%) more ED presentations; 12.5% (95% CI 1.7–24.8%) more acute hospital admissions; with no differences in ICU admissions. Pain and complications of cancer accounted for the majority of overall ED presentations. Of the 166 patients who received chemotherapy within 30 days of death, 23 (24.5%) had a late PCR and 12 (16.7%) an early PCR, with no association of PCR status either unadjusted or adjusted for age or gender. The majority of patients (55.8%) died at the inpatient palliative care unit.

Conclusion

Our findings reaffirm the benefits of early PCR for pancreatic cancer patients to avoid inappropriate care toward the EOL. We suggest that in modern cancer care, there can sometimes be a need to reconsider the use of the term ‘aggressive cancer care’ at the EOL when the care is appropriately based on an individual patient’s presenting physical and psychosocial needs. Pancreatic cancer patients warrant early PCR but the debate must thus continue as to how we best achieve and benchmark outcomes that are compatible with patient and family needs and healthcare priorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is unsettling for patients and their families, with late presentations at diagnosis and new therapeutic agents offering only modest improvements in survival [1, 2]. The median overall survival of metastatic pancreatic cancer is 8–11 months and the median overall survival of locally advanced (but not metastatic) inoperable pancreatic cancer is 12–14 months [3, 4]. Currently, less than 5–7% of Australians diagnosed with metastatic disease survive beyond five years [5]. Patients often experience significant physical symptom burden, treatment side effects, and psychosocial burden leading to depression and anxiety [6]. Despite pancreatic cancer being the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States of America [7] and Europe [8] and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in Australia [9], few studies have examined the impact of palliative care on the quality of end-of-life (EOL) care received in this patient cohort [10, 11].

Quality EOL indicators to evaluate the use of aggressive treatments toward the EOL for cancer patients are increasingly recommended and endorsed by peak bodies, including the National Quality Forum [12] and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Quality Oncology Practice Initiative [13]. Traditionally, aggressive cancer care received toward the EOL can be defined as any of the following: use of chemotherapy in the last 14 [14] or 30 days [11] of life, emergency department (ED) presentation, acute hospital/intensive care unit (ICU) admission within 30 days of death or death in ICU, and late referral to hospice/palliative care services (≤3 months from referral to death) [15, 16]. Studies have shown that cancer patients experience more aggressive treatments toward the EOL when they are younger, diagnosed with hematological cancers, have distant metastatic disease, poor prognostic tumors, and are managed by oncologists and in teaching hospitals [11, 17, 18].

EOL care however, is enhanced in cancer patients when palliative care is integrated early and provided for a longer duration, particularly after discontinuing chemotherapy [19]. Nonetheless, reports of chemotherapy use for patients with varied cancer diagnoses within the last month of life remains wide-ranging from less than 8 to 45.5% [11, 20, 21]. A retrospective cohort study of 366 cancer patients found that those referred early to palliative care benefited at the EOL through more hospice inpatient utilization (74% versus 47%, adjusted p < 0.001) [22] and fewer emergency room visits (39% vs. 68%, p < 0.001), hospitalizations (48% vs. 81%, p < 0.003) and hospital deaths (17% vs. 31%, p = 0.004) in the last 30 days of life. Furthermore, when EOL care planning discussions occurred, patients received less acute care within 30 days of death (OR: 0.67; p = 0.025) [15].

Data relating specifically to the use of aggressive treatments toward the EOL for pancreatic cancer patients remain limited. American surveillance data (comparing data from 1992 to 1994 and 2004–2006) has shown that despite an increase in hospice enrollment of pancreatic cancer patients, admissions to ICU and chemotherapy use in the last month of life increased significantly from 15.5 to 19.6% (p < 0.0001) and 8.1 to 16.4% (p < 0.0001) respectively [23]. A Swiss study of 231 pancreatic cancer patients similarly showed that 24% of patients received chemotherapy in the last 4 weeks of life, with the median survival from last chemotherapy to death being 7.5 weeks (95% CI 6.7–8.4) [24]. Conversely a retrospective population cohort study of 5381 Canadian patients with advanced pancreatic cancer found that PCR was associated with less chemotherapy treatment (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.25–0.46), fewer ICU admissions (OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.08–0.18), reduced emergency department visits (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.16–0.23), and fewer hospitalizations near death (OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.19–0.31) [10]. Similarly, a Taiwanese study showed that pancreatic cancer patients receiving inpatient palliative care compared to acute hospital care were more likely to receive opioids (84.4% vs. 56.5%, respectively; p < 0.001), had shorter acute hospital stays (10.6 ± 11.1 days vs. 20.6 ± 16.3 days, respectively; p < 0.001), fewer aggressive procedures, and lower medical costs (both, p < 0.005) [25].

The poor survival outcomes and high symptom burden experienced in pancreatic cancer makes it the ideal prototype cancer to study the quality of EOL care. This study, conducted at a single health service, aimed to examine associations between timing of PCR and aggressive cancer care received by pancreatic cancer patients in the last 30 days of life.

Methods

Design

We conducted a retrospective observational study of a prevalent cohort of all patients registered with a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer between January 2012 and December 2016 in a single institution. We included patients over the age of 18 who were registered patients with Cabrini Health, who had received a referral to the palliative care service and who subsequently died. Follow up data was available until March 2017. Ethics approval was obtained from Cabrini Health’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Number: 06–19–06-17). The hospital’s administration provided consent to review patient records and utilize data for the purpose of this study. The Strobe statement was used as a guideline in preparation of this manuscript [26].

Setting

The data was obtained from a large not-for-profit, private health care service providing acute, sub-acute and community based care across six campuses in Melbourne, Australia. The Health Service has 31 accredited medical oncologists consulting across two sites, both providing chemotherapy services through day oncology clinics. In 2016, there were 3398 new cancer diagnoses registered, along with 24,551 same day and 9367 overnight episodes of care. Specialist palliative care is provide via a large integrated service incorporating a 22 bed inpatient unit, community service, supportive care clinics and consult services at no cost to the patient.

Data sources and outcomes

The hospital’s administrative database was used to identify eligible patients using the International Classification of Diseases [27] Code C25.0 to C25.9 and who had a death registered on the database (C25.0-C25.9 describes the diagnosis ‘malignant neoplasm of pancreas’ in more detail). Confirmatory data on further deaths were obtained through the state department’s register of deaths. We captured basic demographic variables (age, sex, country of birth, date and place of death).

Clinical electronic and written case records and the hospital chemotherapy drug administration database were subsequently examined to identify key indicators of aggressive cancer care in the last 30 days of life which included: intravenous chemotherapy use, multiple emergency department presentations and acute hospital admission (defined as ≥1), or intensive care admission (≥ 1). We included chemotherapy administration in external hospitals if these data were available in the clinical records, as patients may have chosen to receive treatment elsewhere. We further determined if referral to the hospitals’ palliative care service had occurred, the interval between referral to palliative care and death, and the place of death. We choose to define early palliative care based on the duration of continuity of palliative care before death [15]. Thus early and late PCR were defined as more than 90 days and less than or equal to 90 days before death respectively.

Statistical analysis

Summary measures of patients’ socio-demographic characteristics were presented as mean (SD), median [25th - 75th percentile] or number (%) according to type and distribution. Unadjusted associations between PCR and measures of aggressive cancer care and place of death used likelihood ratio chi-squared statistic based on a univariable logistic model, and the associations were also tested using a multivariable logistic model to adjust for age and gender. Strength of association is presented as either odds ratio (OR) or risk difference (RD) and the associated 95% confidence interval. There was no missing data except for four patient files which did not have information on chemotherapy usage. No imputations were made. The two-sided significance level was set at 0.05 and no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata v 15 statistical software [28].

Results

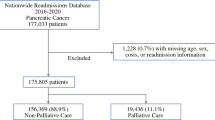

We identified 457 patients with a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer over the study period. Of these, 278 met the eligibility criteria of being registered with the health service with a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, receiving a referral to the hospital’s palliative care service, more than 18 years of age and dying within the study period. Patient characteristics by PCR status are presented in Table 1. Compared to patients receiving late PCR those with an early PCR were younger, with mean difference 5.1 (95%CI 2.2 to 8.0) years. The median time between referral and death was 48 days, with 187/278 (67.3%) of patients categorized as receiving a late PCR and 91/278 (32.7%) receiving an early PCR.

Emergency department presentation, acute hospital and intensive care unit admission.

Measures of aggressiveness of cancer care are summarized in Table 2. One hundred and one (36.3%) patients presented to the ED within the last 30 days of life and, of these, 15 (14.9%) had more than one admission. Those with a late PCR were 18.1% (95%CI 6.8–29.4%, p = 0.003) more likely to have an ED presentation than those with an early PCR. Reasons for ED presentation were widely varied (see Table 2) with main reasons including pain, nausea, vomiting and complications of cancer (e.g. biliary obstruction and ascites) and infection. One hundred and seventy (61.2%) patients had an admission to the acute hospital in the last 30 days of life, with 19 (6.8%) having more than one admission. There is moderate evidence that late PCR is associated with a 12.5% (95%CI 1.7–24.8%, p = 0.04) higher acute hospital admission rate compared to early PCR (Table 3). Furthermore, the number of admission episodes is increased in those receiving late PCR compared to those receiving early PCR in the last 30 days of life (Table 2). Based upon a total of 191 admission episodes, 31.4% were discharged home, 38.7% transferred to an inpatient palliative care unit and 28.8% died in hospital. Only 3 (1.1%) patients had an ICU admission in the last 30 days of life and there were no deaths in the ICU. There was also no association between the timing of PCR and patients’ place of death (Table 3).

Chemotherapy use

Details of chemotherapy use are summarized in Fig. 1. Overall 170 (61.2%) patients were recorded as having received intravenous chemotherapy at any one time during the study period. Those patients with early PCR were more likely to receive chemotherapy at any time compared to those with late PCR [risk difference 28.3% (95%CI 17.4 to 39.2, p < 0.001)] (Table 3). Overall, 108 (38.8%) did not receive chemotherapy due to advanced nature of the illness at diagnosis, high risk due to comorbidities or patient refusal. Details for the use of chemotherapy within 30 days of death was available for 166 patients. Twenty-three patients (24.5%) received chemotherapy with late PCR and 12 (16.7%) with early PCR within 30 days of death. There was no association of chemotherapy usage within 30 days of death and PCR status either unadjusted or adjusted for age or gender (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first Australian study to examine EOL outcomes in a cohort of pancreatic cancer patients referred to a palliative care service and its association with timing of PCR. Given that a recent systematic review demonstrated a 98% loss of healthy life in pancreatic cancer patients [29], it is paramount that due vigilance is given to the EOL care experience of patients and caregivers. The ASCO practice guidelines for metastatic pancreatic cancer recognizes palliative care as an important adjunct in management and recommends early initiation of a referral, preferably at the first visit [6]. This recommendation is further validated by findings from a recent multicenter Delphi study undertaken to establish an international core set of patient reported outcomes (PROs) in pancreatic cancer [30]. Eight PRO’S rated as ‘very important’ by patients (curative- and palliative-setting) and health care professionals were: general quality of life, general health, physical ability, ability to work/do usual activities, fear of reoccurrence, satisfaction with services/care organizations, abdominal complaints (pain/discomfort) and relationship with partner/family.

There remains ambiguity as to what constitutes an early referral to palliative care, with figures ranging from > 3 months before death [15, 22, 31] to 6–14 months prior to death [32]. Only a third of our patient cohort (32.7%) received an early PCR (> 3 months before death). This compares to 10.1% of 922 [31] and 33% of 366 [15] patients with all cancer types in single American institutions. Additionally our median time between referral to death was 48 days. This compared to Bennett et al. who found the median duration of palliative care involvement before death across 3 services in the United Kingdom was 37 days, with differences in duration identified between cancer and non-cancer patients (16 versus 22 days) and setting of care (community or the acute hospital; 22 days versus 13 days). There was a statistical difference (p = < 0.001) between cancer types, with prostate or breast cancer having the longest time (median days of 43.5 and 48 days respectively) and hematological and head and neck cancers having the shortest time (median 26 days) [32]. A similar retrospective Irish study conducted across an integrated palliative care service found that mean time from referral to death interval was 70 days, with the majority receiving care across more than one setting [33].

Studies have also demonstrated that longer referral-to death interval increases likelihood of dying at home or in an inpatient hospice [34] and the intensity of palliative care follow up is associated with fewer instances of aggressive treatments used near death, with the minimum number of palliative care contacts needed to benefit ranging between three and four [10]. Additionally, home has been shown to be the preferred place of death for the majority of cancer patients [35] and those never admitted to an inpatient palliative care unit, whilst those with at least one admission to an inpatient palliative care unit have shown preference for care in this setting [32]. Despite our findings demonstrating no association between timing of PCR and place of death, the majority (55.8%) of patients died in the inpatient palliative care unit, with only a fifth (20.5%) dying at home/residential care facility. We did not collect data on the intensity of palliative care follow up following referral that may have influenced this outcome. In this cohort with pancreatic cancer, the location for death for a pancreatic cancer patient may have been influenced by poorly controlled symptoms and complications of cancer as detailed in Table 2, necessitating the availability of expert care. The additional perceived burden on others and security with the familiarity of staff and environment [36] may have been contributing factors. Our high death rates in the inpatient palliative care unit may also be attributed to our model of early integration palliative care [37], which facilitates admission for symptom control and rehabilitation through the illness trajectory and not simply EOL care. 38.7% of those admitted into hospital were subsequently transferred to the inpatient palliative care unit, thus increasing the likelihood of patients having one or more admissions to an inpatient palliative care unit pre-death, possibly influencing preference for care in the this setting toward the EOL.

When evaluating quality indicators for care of cancer patients in their last days of life, Raijmakers et al. found that > 80% of respondents agreed that < 4% of patients who die should have > 1 ED visit, > 1 hospitalizations or have an ICU admission in the last 30 days [38]. Our findings were contrary to these recommendations, with just over a third (36.3%) of patients presenting to the ED and close to two thirds (61.2%) having an acute hospital admission in the last 30 days of life. Additionally, 14.9% had > 1 ED presentations and 6.8% > 1 hospital admission. Nonetheless, ED presentations and hospital admissions remain common in patients with advanced cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 studies by Henson et al. examined ED attendance by cancer patients in their last month of life [39]. It described contributing demographic, clinical and environmental variables that increased the likelihood of ED presentations which included being male and of black race, having lung cancer, lower socioeconomic status and without a PCR [39]. Worsening symptoms, treatment toxicity and caregiver stress have also been shown to contribute to ED visits [40] as found in our study (Table 2). Nonetheless, our findings supported the findings of Hui et al. [15], confirming benefits of early palliative care, with a late PCR increasing the likelihood of ED presentations and number of hospital admissions in this cohort.

These contradictory findings of seemingly aggressive cancer care supports the findings of Wijnhoven et al. who in a qualitative study exploring the impact of incurable cancer (pancreatic and non-small cell lung cancer) on family members and primary care-givers suggests that ED presentations and hospital admission may be considered to be part of necessary treatment as opposed to avoidable burdens [41]. Figure 2 demonstrates the integrated model of care at the study site, demonstrating how symptom complexity, psychosocial distress, lack of inpatient palliative care beds or staffing may lead to ED or acute hospital presentations. Patient and caregiver strain can be significant when patients experience the array of symptoms and complications that may arise with pancreatic cancer as shown in our findings. Pain is associated with reduced survival in pancreatic cancer and affects up to 80% of patients, with 50% requiring strong opioid analgesia [42]. Depression together with anxiety affects 33–50% of patients [43], influencing overall quality of life and the social, emotional and functional wellbeing of both patient and caregiver. Complications may include obstruction, ascites and thromboembolism [6], all of which cause significant symptomology and require acute medical intervention.

Patient flow through an integrated model of care Images depicted in Fig. 2 were adapted from icons by Freepik, Smartline and Smashicons from www.flaticon.com

Finally, the use of chemotherapy in situations that are deemed futile remains common in cancer, with its use sometimes being justified as a means to reinforce hope in dire situations [44]. This collusion of hope may be unnecessary if honest conversations and early involvement of palliative care service are used to assist patients and families come to terms with the inevitable outcome. In our study, we failed to categorize the cohort to those with potentially curable, locally advanced or metastatic disease and failed to exclude those with a diagnosis of an additional cancer. These factors may have contributed to chemotherapy use in the small cohort of 35 (20.6%) of the 170 patients who received treatment in the last 30 days of life.

Conclusion

Our findings mirror the results of a small number of international studies and reaffirm the benefits of early referral to palliative care for pancreatic cancer patients to avoid futile treatment and inappropriate care toward the EOL [10, 23, 25]. We however question the current benchmarks for aggressive cancer care at the EOL, based on our findings that patients with significant symptoms and whose caregivers lack support appropriately require acute hospital service utilization or care in a supported environment. We suggest that in modern cancer care, there can sometimes be a need to reconsider the use of the term ‘aggressive cancer care’ at the EOL when the care is appropriately based on an individual patient’s presenting physical and psychosocial need [45]. For pancreatic cancer patients, the wide spectrum of significant symptomology experienced and the condensed time frame associated with the diagnosis may appropriately justify the use of acute services and treatments at this point of life.

Ironically, the widespread use of what is traditionally described as aggressive treatments in the final month of life may paradoxically rise with palliative care integration earlier in the disease trajectory and into the acute setting, as symptom burden is appropriately managed, unless outreach community services develop alternate solutions to reduce hospital presentations and maintain care in the community. The debate must thus continue as to how we best achieve and benchmark outcomes that are compatible with patient and family needs, informed views, experiences and healthcare priorities.

Abbreviations

- ASCO:

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- ED:

-

Emergency Department

- EOL:

-

End-of-life

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- PCR:

-

Palliative Care Referral

- PRO:

-

Patient Reported Outcomes

- RD:

-

Risk Difference

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

References

Saluja AK, Dudeja V, Banerjee S. Evolution of novel therapeutic options for pancreatic cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0000000000000298.

Sherman DW, McGuire DB, Free D, Cheon JY. A pilot study of the experience of family caregivers of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer using a mixed methods approach. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:385–399.e381–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.006.

Vogel A, Rommler-Zehrer J, Li JS, McGovern D, Romano A, Stahl M. Efficacy and safety profile of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer treated to disease progression: a subanalysis from a phase 3 trial (MPACT). BMC Cancer. 2016;16:817. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2798-8.

Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. New Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–25. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011923.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2017. Cancer Compendium: information and trends by cancer type. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-survival-and-prevalence-in-australia-perio/data. Accessed 24 Apr 2019.

Sohal DP, Mangu PB, Khorana AA, Shah MA, Philip PA, O'Reilly EM, et al. Metastatic pancreatic Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2784–96. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.1412.

Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–21. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-14-0155.

Pancreatic Cancer Europe. 2018. https://www.pancreaticcancereurope.eu/. Accessed on 16 Oct 2018.

Cancer Australia. 2017. All cancers in Australia. https://canceraustralia.gov.au/affected-cancer/what-cancer/cancer-australia-statistics. Accessed on 14 Apr 2018.

Jang RW, Krzyzanowska MK, Zimmermann C, Taback N, Alibhai SM. Palliative care and the aggressiveness of EOL care in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 107. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju424.

Adam H, Hug S, Bosshard G. Chemotherapy near the EOL: a retrospective single-Centre analysis of patients’ charts. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684x-13-26.

Burke HB. Improving the safety and quality of cancer care. Cancer. 2017;123:549–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30438.

McNiff K. The quality oncology practice initiative: assessing and improving care within the medical oncology practice. J Oncol Pract. 2006;2:26–30. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2006.2.1.26.

Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the EOL: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3860–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.15.8253.

Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ, Block S. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of EOL cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1133–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.03.059.

Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, Dev R, Chisholm G, Bruera E. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of EOL care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743–9.

Tang ST, Wu SC, Hung YN, Chen JS, Huang EW, Liu TW. Determinants of aggressive EOL care for Taiwanese cancer decedents, 2001 to 2006. J Clinic Oncol. 2009;27:4613–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.20.5096.

Hui D, Didwaniya N, Vidal M, Shin SH, Chisholm G, Roquemore J, Bruera E. Quality of EOL care in patients with hematologic malignancies: a retrospective cohort study. Cancer. 2014;120:1572–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28614.

Davis MP, Temel JS, Balboni T, Glare P. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4:99–121. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.04.04.

Ahluwalia SC, Tisnado DM, Walling AM, Dy SM, Asch SM, Ettner SL, et al. Association of early patient-physician care planning discussions and EOL care intensity in advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:834–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.0431.

Taberner Bonastre P, Taberner Bonastre MT, Soler Company E, Perez-Serrano Lainosa MD. Chemotherapy near the EOL; assessment of the clinical practise in onco-hematological in adult patients. Farm Hosp. 2016;40:14–24. https://doi.org/10.7399/fh.2016.40.1.8918.

Amano K, Morita T, Tatara R, Katayama H, Uno T, Takagi I. Association between early palliative care referrals, inpatient hospice utilization, and aggressiveness of care at the end-of-life. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:270–3. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.0132.

Sheffield KM, Crowell KT, Lin YL, Djukom C, Goodwin JS, Riall TS. Surveillance of pancreatic cancer patients after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1670–7. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-2152-y.

Frigeri M, De Dosso S, Castillo-Fernandez O, Feuerlein K, Neuenschwander H, Saletti P. Chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: too close to death? Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:157–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1505-9.

Wang JP, Wu CY, Hwang IH, Kao CH, Hung YP, Hwang SJ, Li CP. How different is the care of terminal pancreatic cancer patients in inpatient palliative care units and acute hospital wards? A nationwide population-based study BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0075-x.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1495–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013.

World Health Organisation. 2018. Classification http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/. Accessed 14 Apr 2018.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 15: College Station TU; 2017.

Carrato A, Falcone A, Ducreux M, Valle JW, Parnaby A, Djazouli K, et al. A systematic review of the burden of pancreatic cancer in Europe: real-world impact on survival, quality of life and costs. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:201–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-015-9724-1.

van Rijssen LB, Gerritsen A, Henselmans I, Sprangers MA, Jacobs M, Bassi C, Busch OR, et al. Core set of patient-reported outcomes in pancreatic cancer (COPRAC): an international delphi study smong patients and health care providers. Ann Surg. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002633.

Scibetta C, Kerr K, McGuire J, Rabow MW. The costs of waiting: implications of the timing of palliative care consultation among a cohort of decedents at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:69–75. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0119.

Bennett MI, Ziegler L, Allsop M, Daniel S, Hurlow A. What determines duration of palliative care before death for patients with advanced disease? A retrospective cohort study of community and hospital palliative care provision in a large UK city. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012576. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012576.

O'Leary MJ, O'Brien AC, Murphy M, Crowley CM, Leahy HM, McCarthy JM, Collins JC, O’Brien T. Place of care: from referral to specialist palliative care until death. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7:53–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000696.

Poulose JV, Do YK, Neo PS. Association between referral-to-death interval and location of death of patients referred to a hospital-based specialist palliative care service. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2013;46:173–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.08.009.

Khan SA, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. EOL care--what do cancer patients want? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:100–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.217.

Waller A, Sanson-Fisher R, Zdenkowski N, Douglas C, Hall A, Walsh J. The right place at the right time: medical oncology outpatients’ perceptions of location of EOL care. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2018;16:35–41. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2017.7025.

Michael N, O'Callaghan C, Brooker JE, Walker H, Hiscock R, Phillips D. Introducing a model incorporating early integration of specialist palliative care: a qualitative research study of staff's perspectives. Palliat Med. 2016;30:303–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315598069.

Raijmakers N, Galushko M, Domeisen F, Beccaro M, Lundh Hagelin C, Lindqvist O, et al. Quality indicators for care of cancer patients in their last days of life: literature update and experts’ evaluation. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:308–16. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0393.

Henson LA, Gao W, Higginson IJ, Smith M, Davies JM, Ellis-Smith C, Daveson BA. Emergency department attendance by patients with cancer in their last month of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clinic Oncol. 2015;33:370–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.57.3568.

Barbera L, Atzema C, Sutradhar R, Seow H, Howell D, Husain A, et al. Do patient-reported symptoms predict emergency department visits in cancer patients? A population-based analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:427–437 e425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.010.

Wijnhoven MN, Terpstra WE, van Rossem R, Haazer C, Gunnink-Boonstra N, Sonke GS, Buiting HM. Bereaved relatives’ experiences during the incurable phase of cancer: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009009. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009009.

Koulouris AI, Banim P, Hart AR. Pain in patients with pancreatic cancer: prevalence, mechanisms, management and future developments. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:861–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4488-z.

Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004:57–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh014.

Buiting HM, Rurup ML, Wijsbek H, van Zuylen L, den Hartogh G. Understanding provision of chemotherapy to patients with end stage cancer: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2011;342. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d1933.

Bolt EE, Pasman HRW, Willems D, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Appropriate and inappropriate care in the last phase of life: an explorative study among patients and relatives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):655.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. David Philips and Simone Reed who assisted with data extraction.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from Menarini Australia Ltd. The funding body was not involved in the design of the study, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, or in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to organizational requirements for release but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NM contributed to study design, study supervision, interpretation of results and wrote the manuscript; GB, AM and WDS contributed to study design, data acquisition and analysis; COC contributed to study supervision, interpretation of the result and critically revised the manuscript for important content; DC contributed to data analysis plan and data analysis; RH contributed to analysis plan, data analysis and interpretation of the results, DK, and JS contributed to study design and interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was approved by Cabrini Health’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Number: 06–19–06-17). Informed consent to participate was not required as this was a retrospective study of deceased patients. All data was de-identified and thus does not compromising anonymity or confidentiality or breach local data protection laws.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

N Michael is a member of the advisory board of Menarini Australia Ltd. All other authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Michael, N., Beale, G., O’Callaghan, C. et al. Timing of palliative care referral and aggressive cancer care toward the end-of-life in pancreatic cancer: a retrospective, single-center observational study. BMC Palliat Care 18, 13 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0399-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0399-4