Abstract

Background

The incidence of human papilloma virus (HPV)-related oral cancer has recently increased worldwide. The role of dentists is of prime importance in the early detection of oral cancer which would result in a favourable outcome for the patients. The aim of the current study was to assess the knowledge, awareness and attitudes of dental students, interns and postgraduate maxillofacial residents at the University of Jordan (UJ) to different aspects of oral cancer, particularly those related to HPV.

Methods

A paper-based survey was conducted at UJ among all pre-clinical dental students (pre-clinical group), clinical dental students, interns and postgraduate maxillofacial residents (clinical group). The survey included five sections comprising 29 items. The sections included questions investigating oral cancer knowledge, oral cancer screening, HPV knowledge and the ability to discuss personal topics with patients.

Results

A total of 376 respondents out of 1052 potential participants completed at least one item of the survey (study coverage of 35.7%). Among the study participants, the pre-clinical group represented 41.2% (n = 155) and the clinical group represented 58.8% (n = 221). The majority of participants in the clinical group showed better knowledge on oral cancer potential anatomic sites, clinical presentation and possible risk factors compared to the pre-clinical group. Most participants in the clinical group (n = 195, 88.2%) correctly identified HPV as a risk factor for oral cancer development. The majority of participants in the clinical group displayed suitable attitude towards oral cancer screening despite their desire for a reliable screening device and additional training in oral cancer screening. A number of limitations in basic knowledge about HPV was noticed among participants in the clinical group particularly related to unawareness of the vaccine availability. The majority of participants in the clinical group displayed hesitancy in discussing personal topics with the patients, including the history of previous sexually transmitted infections and sexual abuse.

Conclusions

Gaps in knowledge regarding HPV-related oral cancer has been detected which necessitate intervention measures including curricular changes, training workshops and awareness campaigns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cancers of the oral cavity, oropharynx and lips represent a growing problem worldwide with an estimated incidence of about 448,000 cases and 228,000 deaths in 2018 [1]. Although the majority of cancers arising from these three sub-sites are squamous cell carcinomas, they have different major etiologic factors (ultra-violet exposure for lip cancer, tobacco, alcohol, and areca-nut chewing for oral cavity cancer, and human papilloma virus [HPV] infection for oropharyngeal cancer) [2, 3]. Furthermore, cancers arising from different anatomic sub-sites exhibit different biologic behaviour, and different prognosis and management [4,5,6].

The high mortality rate associated with oral cancer is related to late presentation of a large proportion of patients with advanced disease [7]. Thus, early diagnosis appears to be of prime importance for achieving a favourable outcome in the patients [8]. Although the oral cavity represents an easily accessible site for clinical examination, the lack of awareness in both the patients and health-care professionals precludes early detection of precancerous and early cancer lesions [9,10,11]. A promising strategy to improve survival among patients with oral cancer is increasing awareness and knowledge among the patients and health-care professionals [12]. Dentists represent a significant sector which faces this problem, thus focusing on this group with educational material is of high value [12]. Identifying the gaps in dental professionals’ knowledge and increasing their confidence in discussing HPV as a sexually transmitted infection (STI) is important to detect early cases [13].

The potential role of high-risk HPV types, particularly HPV-16 as risk factors for the development of oral cancer has been elucidated for decades [14, 15]. Additionally, the burden of HPV-related oral cancer is increasing worldwide [16, 17]. Various studies from developed countries (e.g. North America, Europe, Japan and Australia) reported that 17–56% of all oral cancers are HPV-related [18]. However, limited data are available from the less developed regions including the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) [18]. HPV infection with malignant strains is likely to play a role in oral cancer in the MENA despite the scarcity of data on this subject including a few studies from Yemen, Sudan, Syria, and Iran [19,20,21,22,23].

Several studies examined knowledge and awareness of patients, students, and dental professionals toward oral cancer in different parts of the world and reported variable results [10, 24,25,26]. Nevertheless, few studies examined knowledge of health care professionals about HPV-related oral cancer and their attitude toward HPV screening and discussing personal topics with patients [27, 28].

Earlier studies from Jordan aimed to assess general knowledge of oral cancer of the dental students, recently graduated medical and dental professionals, and among the patients [10, 29, 30]. However, no previous reports have been found in Jordan that assessed knowledge of HPV-related oral cancer among dental students. Thus, the objectives of the current project were: (1) to assess the general knowledge of dental students at the University of Jordan (UJ) regarding different aspects of oral cancer (anatomic sites, clinical presentation and risk factors). (2) to evaluate the attitude of clinical students regarding screening of oral cancer. (3) to assess the knowledge of dental students at UJ regarding different aspects of HPV infection. (4) to assess the attitude of the clinical students regarding the discussion of personal topics with patients.

Methods

Study participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted using a paper-based questionnaire that was distributed among pre-clinical doctor of dental surgery (DDS) students (2nd and 3rd year students), clinical DDS students (4th and 5th year students), interns, and postgraduate maxillofacial residents at the University of Jordan (UJ) and Jordan University Hospital (JUH). The survey was distributed among potential participants during December 2018 and January 2019. In subsequent analysis, the pre-clinical students were considered as one group “pre-clinical” and the 4th year, 5th year DDS students, interns and postgraduate residents were considered as a second group “clinical”.

At the time of manuscript writing, the DDS program at UJ comprised 196 credit hours distributed over five years. The curriculum first year entails basic science courses and elective courses and is considered a pre-med foundation year with candidates divided into the doctor of medicine program and into the DDS program. Pre-clinical courses taken during the second and third curriculum years include basic medical and dental sciences. The start of clinical courses is from the summer semester of the third year. Internship is a one-year period and postgraduate maxillofacial residency training entails clinical rotations for four years and the residents are also considered as postgraduate students.

The target study population was all DDS students from 2nd year up till postgraduate residents with the aim of reducing coverage error of the survey. The total number of potential study participants was 1052, distributed as follows: 2nd year (n = 337), 3rd year (n = 257), 4th year (n = 199), 5th year (n = 202), interns (n = 45) and postgraduate maxillofacial residents (n = 12).

Ethical permission

The study was approved by the JUH institutional review board (IRB/296/2018) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. An informed consent was taken from every participant verbally, and the collected data were treated confidentially.

Data collection

The survey items were adopted from previous studies among dentists and dental students in USA, Netherlands and Spain [26, 31, 32]. To assess the time needed to complete the survey, question wording, survey flow, and choice of response, a pilot test was performed on randomly selected participants from the pre-clinical and clinical groups (n = 10). Electronic-based survey was sent by e-mail (n = 5) and the paper-based survey (n = 5) was distributed in-person. No response was obtained from the five participants who received the survey by e-mail as compared to 100% response rate in the paper-based pilot survey. Hence, it was decided to conduct this study using the paper-based format. English language was used to conduct the survey as English is the official teaching language of dentistry at UJ. Minor modifications were made according to the results of pilot test, and the results of this pilot testing were not included in the final analysis. The final version of the survey took approximately 5–10 min to complete. Surveys were distributed at the beginning or the end of classes at lecture rooms for the DDS students. For interns and postgraduate residents, participation was offered in-person in the Department of Dentistry, JUH. In all cases, participation was voluntary and anonymous. The students were informed of the nature of the study through an information section at the start of the survey. Then, the self-administered survey was distributed and collected back after about 10 min.

Survey items

The survey items were constructed in light of the study objectives that were mentioned previously in the introduction section. The survey comprised five sections, each of which consisted of several items with a total of 29 items in the entire questionnaire. The first section included questions on age, gender, nationality and current level of education. The second section included items related to oral cancer knowledge (anatomic sites, early signs, clinical presentation and risk factors). The third section included items related to attitude towards oral cancer screening. The fourth section was about HPV knowledge. The final section included items related to discussing personal topics with the patients (Additional file 1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted through IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 for Windows. Two-sided Fisher’s exact test (FET) and Mann-Whitney U test (M-W) were used when appropriate. To compare the mean score for certain survey items across different educational levels, we used the Kruskal-Wallis (K-W) test. To compare the scores stratified by gender and nationality that were associated with being comfortable in asking the patients about personal topics, two-sided independent samples t-test was used. Statistical significance was considered for p < 0.050. To calculate the sample size margin of error, “Sample size calculator” available freely online from CheckMarket (“Sample size calculator”, CheckMarket, https://www.checkmarket.com/sample-size-calculator/. accessed 3 May 2019) was used.

Results

Study participants

A total of 376 participants out of 1052 potential participants completed at least one item of the survey yielding a study coverage of 35.7%. A hundred and fifty five participants were pre-clinical students (41.2%) and 221 participants were clinical students, interns and postgraduate residents (58.8%). The response was higher among the clinical group compared to the pre-clinical group (48.3% vs. 26.1%, p < 0.001, FET). The details of participants’ distribution were as follows: second-year pre-clinical students (n = 70, 18.6%), third-year pre-clinical students (n = 85, 22.6%), fourth-year clinical students (n = 124, 33%), fifth year clinical students (n = 67, 17.8%), interns (n = 24, 6.4%) and postgraduate residents (n = 6, 1.6%). The highest response rate was among the 4th year students (124/199, 62.3%), followed by the interns (24/45, 53.3%), postgraduate residents (6/12, 50.0%), 5th year students (67/202, 33.2%), 3rd year students (85/257, 33.1%) and 2nd year students (70/337, 20.8%). The calculated sample size margin of error was 4.06%, considering the 95% confidence level.

About three-fourths of the study population were females (n = 280), and the median age of the study participants was 21 years (mean: 21.2, interquartile range [IQR]: 20–22, Table 1). Gender-based comparison of age revealed no differences (median age 21 years for both, IQR: (20-22) vs. (20-23) for males and females, respectively, p = 0.168, M-W). Of the whole study sample, 57.7% of the students were Jordanians whereas 15.7% where of non-Jordanian citizenship (of 13 nationalities and 94.8% of non-Jordanian students came from the MENA countries). Data on nationality were missing for 100 participants (26.6%).

Oral cancer knowledge

All participants in the clinical group stated that they heard of oral cancer (n = 221) compared to 79.4% (n = 123) of the participants in the pre-clinical group (p < 0.001, FET, Table 2).

Regarding the possible anatomic locations for oral cancer, the vast majority of the participants in the clinical group correctly identified the tongue and floor of the mouth (96.8 and 90.5% respectively). However, a considerable percentage of the participants in the clinical group did not recognize the following as potential sites for oral cancer: lips (42.1%), palate (39.4%), jaw bone (38.9%) and buccal mucosa (35.3%). Higher percentage of correct identification of oral cancer anatomic sites was observed in the clinical group compared to the pre-clinical group, except for the buccal mucosa (p = 0.351, Table 2, Additional file 2).

A considerable percentage of the participants in the clinical group did not recognize the following as possible oral cancer early signs: mass (48.4%), red lesion (39.4%), ulcer (37.6%) and white lesion (29.9%). However, the participants in the clinical group were more likely to correctly identify early signs of oral cancer compared to the pre-clinical group for all items (Table 2, Additional file 2).

For the clinical manifestations of oral cancer, the clinical group showed better knowledge in all items compared to the pre-clinical group and the majority correctly identified lymph node enlargement as a sign for oral cancer (86.4%). However, a large percentage of the participants in the clinical group failed to identify difficulty in swallowing (37.1%), tooth mobility and mucosal bleeding (49.8% for both) as signs and symptoms of oral cancer (Additional file 2).

Regarding the risk factors for oral cancer, the vast majority of participants in the clinical group correctly identified smoking (97.7%), HPV (88.2%), alcohol consumption (87.8%) and family history of oral cancer (76.0%) to be associated with the disease. However, a large percentage failed to identify sun exposure (53.8%) and severe anemia (68.3%) as possible risk factors for oral cancer. The clinical group showed significantly higher percentage of knowledge compared to the pre-clinical group (p < 0.001 for all comparisons, FET, Additional file 2).

Oral cancer screening

Regarding the frequency with which the participants in the clinical group examine patients for signs of oral cancer, the most common response was only to new patients in their first visit (n = 78, 36.8%). Slightly less than one-third of the participants in the clinical group reported that they will screen patients at every visit (n = 67, 31.6%), whereas more than a fourth of the participants in the clinical group reported that they only examine patients for signs of oral cancer if they suspect something (n = 57, 26.9%). Ten participants in the clinical group reported that they never or rarely examine their patients for signs of oral cancer (4.5%). Postgraduate residents were more likely to screen patients at every visit (50.0%) followed by interns (41.7%), 5th year students (40.0%) and 4th years students (23.9%), however this difference lacked statistical significance (p = 0.059, K-W, Fig. 1a).

Regarding the visual screening of oral cancer and on a scale from 1 to 5 (where 5 being the most confident), postgraduate residents showed the highest level of confidence (mean = 4.5, standard deviation [SD] = 0.55) followed by interns (mean = 2.79, SD = 0.88), 5th year clinical students (mean = 2.66, SD = 0.89) and lastly 4th year students (mean = 2.49, SD = 0.98, p < 0.001; K-W). Regarding manual palpation as a screening method for oral cancer and on a scale from 1 to 5 (where 5 being the most confident), postgraduate residents showed the highest level of confidence to perform screening (mean = 4.5, SD = 0.55), followed by 4th and 5th year clinical students (mean = 2.65, SD = 1.01 for both) and lastly interns (mean = 2.58, SD = 0.72, p = 0.002, K-W, Figs. 1b and c). No statistically significant differences were observed upon comparing gender and nationality groups regarding attitude towards screening (comparisons were done using t test).

The majority of clinical students reported that a reliable screening device for oral cancer is needed (n = 196, 92.9%) and that they need additional training on screening (n = 198, 93.4%).

HPV knowledge

All participants in the clinical group who provided responses stated that they heard of HPV prior to participation in the survey (n = 214) compared to 65.0% (n = 52) of the participants in the pre-clinical group (p < 0.001, FET, Table 2).

A majority of the participants in the clinical group showed superior knowledge on HPV compared to the pre-clinical group participants, through providing correct responses to the following items: HPV can cause oral cancer (97.2% vs. 82.7%, p < 0.001), HPV can cause an STI (92.8% vs. 82.7%, p = 0.032) and that a person can have HPV without knowing it (91.0% vs. 75.5%, p = 0.004). In addition, participants in the clinical group showed better knowledge compared to the pre-clinical group participants in the following items: HPV causes AIDS (73.0% vs. 53.8%, p = 0.011) and HPV causes herpes and cold sores (56.9% vs. 24.5%, p < 0.001). We found no statistically significant difference in knowledge upon comparing the clinical and pre-clinical groups for the following items: Certain strains of HPV causes cervical cancer (94.8% vs. 88.7%, p = 0.121) and antibiotics can cure HPV infection (86.9% vs. 75.5%, p = 0.054). Both clinical and pre-clinical groups showed low level of knowledge to the following items without statistically significant difference: there is a vaccine for HPV (36.8% vs. 44.0%, p = 0.419) and most HPV infections resolve within a short period of time (22.1% vs. 32.0%, p = 0.145, FET for all comparisons, Additional file 2).

The stratification of the clinical group by level of education (4th year, 5th year, interns and residents) revealed statistically significant differences in HPV knowledge to the following items: there is a vaccine for HPV (28.8, 44.6, 60.9 and 16.7% correct responses among 4th year, 5th year, interns and residents respectively, p = 0.009, K-W) and most HPV infections resolve within a short period of time (26.3, 10.8, 34.8 and 16.7% correct responses among 4th year, 5th year, interns and residents respectively p = 0.041, K-W, Fig. 2).

Human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge among the clinical students at the University of Jordan. The survey items are stratified by level of education. P values were calculated using Kruskal-Wallis test. AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. STI: sexually transmitted infection. Statistically significant values are shown in red

The vast majority of the participants in the clinical group (97.2%) reported that it is important to enhance knowledge about HPV related oral cancer to the public. A majority of the participants in the clinical group (68.8%) stated that the best way to inform patients about HPV is to tell them that HPV can cause oral cancer compared to 31.2% who stated that the best way to inform patients about HPV is to tell them that the virus is associated with STI.

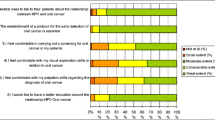

Discussing personal topics with patients

The responses were scored on the three items related to discussing personal topics with patients as follows: 1 = not comfortable at all, 2 = slightly comfortable, 3 = somewhat comfortable, 4 = moderately comfortable and 5 = most comfortable. Regardless of level of education, the majority of participants in the clinical group reported higher confidence in asking patients about their life style (mean = 3.74, SD = 1.19). However, confidence level decreased in relation to STI (mean = 2.34, SD = 1.24) and to sexual abuse (mean = 2.07, SD = 1.28). Stratified by gender, males were more comfortable than female participants to ask patients about STI (2.76 vs. 2.21, p = 0.005, t-test). Male participants had higher mean for the other two items but without statistical significance (Fig. 3).

Attitude of clinical students at the University of Jordan towards discussing personal topics with patients. We scored the responses on the three items as follows: 1 = not comfortable at all, 2 = slightly comfortable, 3 = somewhat comfortable, 4 = moderately comfortable and 5 = most comfortable. The survey items are stratified based on gender, nationality and age. P values were calculated using the two-sided independent samples t-test

In addition, Jordanian participants were more reluctant to ask about STI compared to non-Jordanian participants (mean = 2.26 vs. 2.81, p = 0.024, t-test). Moreover, older participants (more than or equal to 22 year (the median age of the clinical group) were more comfortable to ask about STI compared to younger participants (2.52 vs. 2.11, p = 0.016, t test, Fig. 3).

Discussion

In the current study, the main objective was to assess knowledge and attitudes of dental students, interns and postgraduate maxillofacial surgery residents at UJ (the oldest and largest University in Jordan), towards HPV-related oral cancer. The UJ is one of two universities in the country that offers dentistry education. The current work was motivated by the accumulating evidence pointing to an increasing prevalence of high-risk HPV types as the underlying etiology for oral cancer worldwide [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. In addition, HPV is anticipated to be the most common risk factor for oral cancer in the next decade [40]. Sufficient knowledge on oral cancer among general practitioners and dentists is critical, since early diagnosis is a decisive factor in reducing the morbidity and mortality from the disease [12, 41].

The assessment of level of knowledge and attitudes of the future dentists is crucial to highlight the limitations of the current curriculum taught locally. Moreover, the results of the study are expected to be beneficial at the country level, and might have an added value at the regional level, since a relatively large percentage of the participants were non-Jordanians and likely to practice dentistry in the neighbouring countries. The emphasis on dental staff awareness and the importance of dentists’ roles in the early diagnosis of oral cancer is invaluable particularly in the developing countries [42, 43].

Oral microbiology is an integral part of the dentistry curriculum. Certain microbes including HPV mandate special focus in dentistry not only in relation to cancer [44]. HPV represents an important pathogen causing oral lesions that are frequently encountered by the dentists, hence deep knowledge is important for the diagnosis and ensuring the patients about the nature of HPV-related oral disease [44].

The main findings of the study can be summarized as follows: First, the results revealed good overall knowledge among the clinical group regarding different aspects of oral cancer compared to pre-clinical group. The commonest anatomic sites, clinical manifestations and risk factors were correctly identified by the majority of the participants in the clinical group. However, a relatively large percentage of the clinical group failed to identify lips, buccal mucosa and palate as potential sites for oral cancer development. Lack of knowledge regarding buccal mucosa is particularly worrisome since these cancers generally have poor prognosis [5]. In addition, more than one-third of the participants in the clinical group failed to identify the frequent early lesions of oral cancer including the hard painless masses and mixed red-white lesions “erytholeukoplastic lesions” which might lead to delay in diagnosis that is associated with less-favourable outcome [45]. For the risk factors of oral cancer, the clinical group showed better results compared to the previous studies that were conducted in Jordan both among dental students and recently graduated medical and dental professionals [29, 30]. This might be related to intervention measures including improved dental education in light of the previous results of studies conducted in Jordan and globally. In addition, the rate of correct identification of smoking, alcohol consumption and HPV as risk factors for the disease was higher than the rates observed in some of the MENA countries among dentists and dental students, but in line with results of studies conducted in the Netherlands, Spain and Saudi Arabia [31, 32, 46,47,48].

Second, the participants in the clinical group showed varying attitudes toward oral cancer screening, with a stepwise increase in confidence to perform visual and manual palpation screening depending on the level of education. Improvements in the local educational curriculum are recommended including emphasizing the importance of conducting oral cancer screening as a routine practice.

Third, the participants in the clinical group showed better overall knowledge regarding HPV compared to participants in the pre-clinical group. Nevertheless, certain gaps were identified concerning basic knowledge of the virus. Despite the fact that oral cancer represents the most ominous outcome for HPV infection in the oral cavity, HPV comprises more than 200 types, with varying oncogenic potential [49]. Knowledge of these types and their associated clinical diseases is indispensable for dentists since HPV infections are common in the oral cavity and can manifest in different ways [44].

Fourth, participants in the clinical group were reluctant to discuss issues related to STI and history of sexual abuse with patients. This was particularly evident among female Jordanian participants. The role of communication with patients to reveal history of STIs and sexual abuse is important since HPV types that are associated with oral cancer are usually transmitted through oral sex [50,51,52]. The aforementioned reluctance might be related to cultural and religious attitude towards discussing these issues in the MENA. However, similar difficulties in discussing these topics were also reported among American dentists and Spanish dental students [26, 32].

Finally, the majority of participants aspire for more training and devices that can aid in oral cancer screening which should be addressed. Possible options include continued education in the form of workshops, practical training sessions and awareness campaigns.

The current study had certain limitations as follows: One limitation inherent in a large number of surveys is the possibility that a fraction of participants responded in a way they believe to be suitable for the authors conducting the survey. During the distribution of the questionnaires to participants, it was attempted to minimize this limitation by declining to answer questions or responding to enquiries regarding the different questionnaire items. Sampling error is another potential limitation as the choice of participants to take part in the study might have been influenced by their previous knowledge on oral cancer and HPV which was evident by the low percentage of the pre-clinical participants who agreed to take part in the study. Non-response error should also be considered in spite of our attempt to formulate clear questions that were assessed and modified using the pilot testing. To reduce coverage error we tried to sample as much students as possible during the narrowest feasible period. Another potential limitation was the female predominance in the sample which might have influence on some results particularly those related to discussion of personal topics with patients. Since the study was conducted in a single institution (UJ), our results might not reflect the overall knowledge and attitudes of dental students in the country. Finally, the higher response rate among fourth year clinical students might be explained by the participation of three authors who are themselves at the same educational level, which might motivated some reluctant respondents to participate.

Conclusions

The majority of the participants in the clinical group at UJ showed better knowledge regarding oral cancer in various survey items compared to the pre-clinical group participants. Nevertheless, gaps in knowledge were observed particularly in aspects related to clinical presentation of the disease which might be an impediment to life-saving intervention measures. The overall knowledge of the participants in the clinical group regarding HPV was satisfactory, albeit with gaps in certain aspects (e.g. availability of vaccine). Participants in the clinical group showed reluctance to discuss topics like STIs and history of sexual abuse with the patients (particularly among female participants). This issue can be addressed through improved educational training programs. Knowledge about HPV-related oral cancer is crucial and is recommended to be taught as an integral part of the basic curriculum and clinical training of dental students. A follow-up comparative study is recommended among medical students.

Abbreviations

- DDS:

-

Doctor of dental surgery

- FET:

-

Two-sided Fisher’s exact test

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- JUH:

-

Jordan University Hospital

- K-W:

-

Kruskal-Wallis test

- MENA:

-

Middle East and North Africa

- M-W:

-

Mann-Whitney U test

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- UJ:

-

University of Jordan

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D, Ferris RL. Head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2008;371(9625):1695–709.

Kumar M, Nanavati R, Modi TG, Dobariya C. Oral cancer: etiology and risk factors: a review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12(2):458–63.

Chen PH, Shieh TY, Ho PS, Tsai CC, Yang YH, Lin YC, et al. Prognostic factors associated with the survival of oral and pharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwan. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:101.

Jan JC, Hsu WH, Liu SA, Wong YK, Poon CK, Jiang RS, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with buccal squamous cell carcinoma: 10-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(2):396–404.

Genden EM, Ferlito A, Silver CE, Takes RP, Suarez C, Owen RP, et al. Contemporary management of cancer of the oral cavity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267(7):1001–17.

Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4–5):309–16.

Baykul T, Yilmaz HH, Aydin U, Aydin MA, Aksoy M, Yildirim D. Early diagnosis of oral cancer. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(3):737–49.

Lingen MW, Kalmar JR, Karrison T, Speight PM. Critical evaluation of diagnostic aids for the detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(1):10–22.

Hassona Y, Scully C, Abu Ghosh M, Khoury Z, Jarrar S, Sawair F. Mouth cancer awareness and beliefs among dental patients. Int Dent J. 2015;65(1):15–21.

Peacock ZS, Pogrel MA, Schmidt BL. Exploring the reasons for delay in treatment of oral cancer. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(10):1346–52.

Messadi DV, Wilder-Smith P, Wolinsky L. Improving oral cancer survival: the role of dental providers. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2009;37(11):789–98.

Dodd RH, Forster AS, Waller J, Marlow LAV. Discussing HPV with oropharyngeal cancer patients: a cross-sectional survey of attitudes in health professionals. Oral Oncol. 2017;68:67–73.

Mork J, Lie AK, Glattre E, Hallmans G, Jellum E, Koskela P, et al. Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(15):1125–31.

Liu X, Gao XL, Liang XH, Tang YL. The etiologic spectrum of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in young patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7(40):66226–38.

Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(36):4550–9.

Hashibe M, Sturgis EM. Epidemiology of oral-cavity and oropharyngeal carcinomas: controlling a tobacco epidemic while a human papillomavirus epidemic emerges. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2013;46(4):507–20.

de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(6):607–15.

Nasher AT, Al-Hebshi NN, Al-Moayad EE, Suleiman AM. Viral infection and oral habits as risk factors for oral squamous cell carcinoma in Yemen: a case-control study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118(5):566–72 e1.

Jalouli J, Ibrahim SO, Sapkota D, Jalouli MM, Vasstrand EN, Hirsch JM, et al. Presence of human papilloma virus, herpes simplex virus and Epstein-Barr virus DNA in oral biopsies from Sudanese patients with regard to toombak use. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39(8):599–604.

Al Moustafa AE, Al-Awadhi R, Missaoui N, Adam I, Durusoy R, Ghabreau L, et al. Human papillomaviruses-related cancers. Presence and prevention strategies in the middle east and north African regions. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(7):1812–21.

Al Moustafa AE, Ghabreau L, Akil N, Rastam S, Alachkar A, Yasmeen A. High-risk HPVs and human carcinomas in the Syrian population. Front Oncol. 2014;4:68.

Saghravanian N, Ghazvini K, Babakoohi S, Firooz A, Mohtasham N. Low prevalence of high risk genotypes of human papilloma virus in normal oral mucosa, oral leukoplakia and verrucous carcinoma. Acta Odontol Scand. 2011;69(6):406–9.

Carter LM, Ogden GR. Oral cancer awareness of undergraduate medical and dental students. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:44.

Kebabcioglu O, Pekiner FN. Assessing Oral Cancer awareness among dentists. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(5):1020–6.

Daley E, Dodd V, DeBate R, Vamos C, Wheldon C, Kline N, et al. Prevention of HPV-related oral cancer: assessing dentists' readiness. Public Health. 2014;128(3):231–8.

Daley E, DeBate R, Dodd V, Dyer K, Fuhrmann H, Helmy H, et al. Exploring awareness, attitudes, and perceived role among oral health providers regarding HPV-related oral cancers. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(2):136–42.

Arora S, Ramachandra SS, Squier C. Knowledge about human papillomavirus (HPV) related oral cancers among oral health professionals in university setting-a cross sectional study. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2018;8(1):35–9.

Alami AY, El Sabbagh RF, Hamdan A. Knowledge of oral cancer among recently graduated medical and dental professionals in Amman, Jordan. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(10):1356–64.

Hassona Y, Scully C, Abu Tarboush N, Baqain Z, Ismail F, Hawamdeh S, et al. Oral Cancer knowledge and diagnostic ability among dental students. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32(3):566–70.

Poelman MR, Brand HS, Forouzanfar T, Daley EM, Jager DHJ. Prevention of HPV-related Oral Cancer by dentists: assessing the opinion of Dutch dental students. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(6):1347–54.

Lorenzo-Pouso AI, Gandara-Vila P, Banga C, Gallas M, Perez-Sayans M, Garcia A, et al. Human Papillomavirus-Related Oral Cancer: Knowledge and Awareness Among Spanish Dental Students. J Cancer Educ. 2018.

Gooi Z, Chan JY, Fakhry C. The epidemiology of the human papillomavirus related to oropharyngeal head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(4):894–900.

Joseph AW, D'Souza G. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2012;45(4):739–64.

Forte T, Niu J, Lockwood GA, Bryant HE. Incidence trends in head and neck cancers and human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal cancer in Canada, 1992-2009. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(8):1343–8.

Chan MH, Wang F, Mang WK, Tse LA. Sex differences in time trends on incidence rates of oropharyngeal and Oral cavity cancers in Hong Kong. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018;127(12):895–902.

Blomberg M, Nielsen A, Munk C, Kjaer SK. Trends in head and neck cancer incidence in Denmark, 1978-2007: focus on human papillomavirus associated sites. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(3):733–41.

Weatherspoon DJ, Chattopadhyay A, Boroumand S, Garcia I. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer incidence trends and disparities in the United States: 2000-2010. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(4):497–504.

Chikandiwa A, Pisa PT, Sengayi M, Singh E, Delany-Moretlwe S. Patterns and trends of HPV-related cancers other than cervix in South Africa from 1994-2013. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;58:121–9.

Startling lack of awareness of HPV-mouth cancer link. Br Dent J. 2017;223:10–752.

Pai SI, Westra WH. Molecular pathology of head and neck cancer: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:49–70.

Zohoori FV, Shah K, Mason J, Shucksmith J. Identifying factors to improve oral cancer screening uptake: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47410.

Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. Oral cancer in developing countries: the time to act is upon us. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2014;7(1):58–9.

Candotto V, Lauritano D, Nardone M, Baggi L, Arcuri C, Gatto R, et al. HPV infection in the oral cavity: epidemiology, clinical manifestations and relationship with oral cancer. Oral Implantol (Rome). 2017;10(3):209–20.

Bagan J, Sarrion G, Jimenez Y. Oral cancer: clinical features. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(6):414–7.

Hashim R, Abo-Fanas A, Al-Tak A, Al-Kadri A, Abu EY. Early detection of Oral Cancer- Dentists' knowledge and practices in the United Arab Emirates. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(8):2351–5.

Alaizari NA, Al-Maweri SA. Oral cancer: knowledge, practices and opinions of dentists in Yemen. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(14):5627–31.

Kujan O, Alzoghaibi I, Azzeghaiby S, Altamimi MA, Tarakji B, Hanouneh S, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of Saudi dental undergraduates on oral cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(4):735–8.

Bzhalava D, Eklund C, Dillner J. International standardization and classification of human papillomavirus types. Virology. 2015;476:341–4.

Martin-Hernan F, Sanchez-Hernandez JG, Cano J, Campo J, del Romero J. Oral cancer, HPV infection and evidence of sexual transmission. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18(3):e439–44.

Brondani M. HPV, oral sex, and the risk of oral cancer: food for thought. Spec Care Dentist. 2008;28(5):183–4.

Nguyen NP, Nguyen LM, Thomas S, Hong-Ly B, Chi A, Vos P, et al. Oral sex and oropharyngeal cancer: The role of the primary care physicians. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(28):e4228.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the participation of the DDS students, interns and postgraduate maxillofacial residents at UJ and JUH in this study. We also would like to thank the teaching staff at the School of Medicine and School of Dentistry at UJ for their help and support of the study.

Funding

We declare that we received no funding nor financial support/grants by any institutional, private or corporate entity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS, AAH, YH, AM and GÖS developed the concept and design of this study and supervised the work. MS, EF, DD, AY and YH contributed to design of the questionnaire. DD, DT and SZ performed the pilot-testing. EF, DD, AY, DT and SZ contributed to data collection by the distribution of the survey. MS performed statistical analyses, prepared tables and figures and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and gave the final approval.

Authors’ information

Malik Sallam: Assistant Professor in Laboratory Medicine at the School of Medicine, UJ and Consultant in Laboratory Medicine at JUH.

Esraa Al-Fraihat: Resident doctor in Laboratory Medicine at JUH.

Deema Dababseh, Duaa Taim and Seraj Zabadi: Fourth year DDS students at the School of Dentistry, UJ.

Alaa’ Yaseen: MSc student at the School of Medicine, UJ.

Ahmad A. Hamdan: Assistant Professor Periodontology at the School of Dentistry, UJ and Consultant in Periodontology at JUH.

Yazan Hassona: Associate Professor in Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine and Special Needs Dentistry at the School of Dentistry, UJ and Consultant in Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine and Special Needs Dentistry at JUH.

Azmi Mahafzah: Professor in Laboratory Medicine at the School of Medicine, UJ and Consultant in Laboratory Medicine at JUH.

Gülşen Özkaya Şahin: Specialist in Clinical Microbiology at the Department of Laboratory Medicine, Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Jordan University Hospital institutional review board (IRB/296/2018) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was taken from all participants verbally, and the collected data were treated confidentially. Verbal consent was obtained from every single participant rather than written consent to keep anonymity of the participants and decrease the time and paper content of the questionnaire. The verbal consent approach was approved by JUH institutional review board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We declare that we have no competing interests nor conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

The paper-based questionnaire template that was used in the study. (PDF 115 kb)

Additional file 2:

Additional results. (PDF 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sallam, M., Al-Fraihat, E., Dababseh, D. et al. Dental students’ awareness and attitudes toward HPV-related oral cancer: a cross sectional study at the University of Jordan. BMC Oral Health 19, 171 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0864-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0864-8