Abstract

Background

This scoping review addressed the question ‘what do we know about stress-related changes in saliva and dental caries in general population?’

Methods

The review was conducted using electronic searches via Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and WoS. All published human studies with both observational and experimental designs were included. Two reviewers independently reviewed eligible articles and extracted the data. The studies’ quality was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool.

Results

Our search identified 232 reports, of which six were included in this review. All six studies were conducted in children and used salivary cortisol as stress marker. The studies varied by design, types of stressors, children’s caries experience, methods of saliva collection. Four studies reported a positive association between saliva cortisol levels and caries (p < 0.05) while the other two reported no association (p > 0.05). The quality of the included studies was weak to moderate.

Conclusions

There is lack of evidence about an association between stress-related changes in saliva and caries. Well-designed longitudinal studies with rigorous measurement technics for stress, saliva and dental caries are necessary. This will help to generate new insights into the multifactorial etiology of caries and provide evidence for a rational method for its control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dental caries remains one of the most prevalent chronic diseases worldwide placing a significant burden on individuals and healthcare systems [1, 2]. Accordingly, in 2010, the Global Burden of Disease Study indicated that more than 2.4 billion people worldwide are affected by untreated dental caries [2]. Caries has negative impact on general health and quality of life of individuals [3]. Pain, decrease in masticatory performance, alteration of diet and nutrition, loss of working hours, as well as unaesthetic appearance and reduction in social activities are direct and indirect sequelae of caries disease [3, 4].

The high prevalence of dental caries in certain groups of the society in combination with limited effectiveness of the traditional education-based efforts to improve oral hygiene behaviors for caries prevention [5, 6] highlights the necessity to develop new strategies in caries control. In this regard, several research groups have emphasized the need for in-depth investigation of psychosocial and biological pathways through which social environment affects dental caries [7,8,9]. Some emerging evidence suggests that stress could have a potential role in caries disease [7, 10, 11]. The link between caries disease and stress can be explained via different pathways. Some of which include (but are not limited to) alterations in life style and unhealthy behaviors (e.g., excessive sugar intake, neglect of oral hygiene) [12,13,14], as well as through stress-induced changes in salivary composition and salivary flow rate [15, 16].

Stress can be defined as a real or interpreted threat to the physiological or psychological integrity of an individual that results in a cascade of physiological and/or behavioral responses of the body to maintain homeostasis [17, 18]. There is a widely-recognized theory of allostatic load which explains the effects of stress on the human body [18]. Under chronic exposure to stress conditions, a ‘wear and tear’ of the allostatic systems (central nervous system (CNS), the autonomic nervous system (ANS), the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA)) accumulate [18]. Over time, the ANS system and HPA axis becomes dysregulated. Excessive secretion of hormone cortisol will overstimulate the glucocorticoid receptors in the body, and will alter the function of certain neurotransmitters (e.g., adrenaline, noradrenalin, serotonin), which can affect the CNS, emotional and cognitive function as well as metabolic and immune systems [18, 19].

Saliva maintains the homeostasis of the oral cavity through various functions such as lubrication, buffering action, maintenance of tooth integrity and antimicrobial activity [20]. Furthermore, salivary proteins/peptides play an important role in the adherence of the oral micro-organisms to the tooth surface [15] and in maintaining the equilibrium between remineralization and demineralization processes [21]. The innervation and secretion of salivary glands are regulated by the ANS system, that in turn, affects salivary proteins concentration and salivary flow rate [22]. Under repeated chronic stress conditions, the ANS system functions and consequently, the salivary glands function can get altered, which may increase risk of dental caries [23, 24]. On the other hand, caries-related chronic pain and dental procedures can in turn be associated with the increase of chronic stress load [25, 26]. Salivary cortisol level has been recognized as a valid measure of active free cortisol and as a potential stress biomarker [27]. Many correlational studies showed a positive association of cortisol levels with chronic diseases such as periodontal diseases, diabetes, cardio-vascular diseases [28, 29] as well as with dental caries [30, 31]. Some experimental studies have shown an increase in cortisol concentration as well as in salivary total protein and secretory IgA after an exposure to experimental stress [23, 32, 33]. In addition, changes in salivary composition and microbial adherence have been shown after experimental stress conditions [15].

Summarizing the above-mentioned evidence, several changes in composition and saliva secretion can occur under stress conditions that in turn may have an association with dental caries. We conducted this scoping review to address the question ‘what do we know about stress-related changes in saliva and dental caries in general population?’ The study objectives were: 1. to map published literature concerning an association between saliva stress-related changes and dental caries; 2. to identify potential knowledge gaps in this area of research.

Methods

Electronic searches and eligibility criteria

The scoping review was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework (2005) as well as by other relevant literature sources focusing on enhancing scoping review methodology [34,35,36]. Based on preliminary broad search and consultation with an expert librarian, the following key words and MeSH terms were determined: dental caries, saliva, salivary proteins, stress, psychological, anxiety, depression. In order to identify the relevant studies, electronic searches were carried out via OVID in Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO (1960 to 2016 Sep week 1), CINAHL (1998 to 2016 Sep week 1) and WoS (1998 to 2016 Sep week 1). The search was complemented by reference tracking in identified articles and manual searchers in dental journals (Caries Research; Journal of Dental Research; Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology from 2011 to 2016 year). The following recourses were used for grey literature search: the TripDatabase; websites of American, Canadian and British Dental Assocoations; the abstracts of IADR meetings (2002–2016). An example of the search strategy in Medline is presented in Appendix 1.

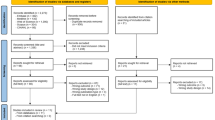

Predefined inclusion criteria were: human studies with both observational (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional) and experimental (randomized clinical trial and quasi-experimental) designs investigating the association between stress-related changes in salivary composition/secretion (flow rate, proteins, salivary stress measures (e.g. cortisol) and dental caries). The search was restricted to articles written in English or French. Studies with insufficient data on salivary characteristics or dental caries, those that included patients with chronic diseases or conditions that can affect salivary function (e.g., Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer), and /or taking medications such as antidepressants or glucocorticoids were excluded. Two reviewers (ST and VD) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the retrieved citations and identified eligible articles for full review. Inconsistency between reviewers was discussed with a third reviewer (EE) and resolved by consensus. All potential relevant studies were retained for full-text assessment (Fig. 1).

Studies’ quality assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP), Canada [37], was used to assess the quality of the included studies. This tool has demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability as well as construct and content validity [38, 39]. The instrument included the following six components: sample selection, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts. Each of these components was rated on a three-point Likert scale (strong, moderate and weak). A study was considered ‘strong’ if there were no weak ratings and with at least four strong ratings out of six. ‘Moderate’ were those with less than four strong ratings and one weak rating. Finally, ‘weak’ included those with two or more weak ratings. Quality assessment was performed independently by each reviewer (ST and VD), inconsistencies were resolved through discussion and with the research method expert (EE) if necessary.

Data extraction and data analysis

Data was extracted using a pre-agreed data extraction form to gather relevant information from each selected study (e.g., authors, study design, study sample, measurement instruments for stress, saliva and caries, main findings), and the extracted data was charted. The charted data was summarized into a narrative synthesis.

Results

Study selection

Our search resulted in a total of 232 publications, of which 6 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the narrative synthesis. The selection process and the general characteristics of the selected studies are presented in Fig. 1 and Table 1 respectively.

Characteristics of studies

The included studies were published between 2010 and 2014 and originated from United States, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Greece and India. Among the six included studies, three were quasi-experimental and three cross-sectional. All six studies were conducted in children with the age range from 4 to 14 years. The sample sizes varied from 30 to 97 individuals in experimental studies and between 64 to 145 participants in observational studies.

The type of stressors varied across studies and they included: various types of dental treatment procedures (e.g., tooth cleaning, fluoride application, placing restorations) in quasi- experimental studies, while caries experience per se, dental pain, low socio-economic status and family financial stress were defined as chronic stressors in the included cross-sectional studies. The methods of saliva collection varied across studies: three studies used stimulated saliva and three studies used unstimulated saliva samples. All six studies used salivary cortisol as a stress marker. All studies used immunoassay system for measuring saliva cortisol. One study measured saliva protein alpha-amylase using enzymatic chromatometry [40]. None of the included studies reported on other salivary proteins. None of the included studies measured the salivary flow rate.

The DMFT(S) (decayed, missed and filed teeth/surfaces) index was used for recording of caries disease in five of the included studies: four studies applied WHO (World Health Organization), 1997 [41] caries diagnostic criteria, one study used diagnostic criteria of Koch, 1970 [42] and one study did not report on this issue.

Quasi-experimental studies

In all of three quasi-experimental studies (Table 1) the salivary cortisol level was measured in children with and without dental caries before and after dental treatment [40, 43, 44]. The baseline caries experience, number of saliva cortisol measurements per day, the specific time of the day, time and number of follow-ups (weeks/months) varied among the studies. In one study, a positive association between pre-treatment salivary cortisol level and caries was reported [44]. In addition, they also observed a steady decrease in the salivary cortisol level in children with rampant caries within three months after dental treatment [44]. Two other studies reported no association between salivary cortisol levels (pre-treatment/post-treatment/recall) and caries [40, 43]. In addition, no association between salivary alpha-amylase levels (pre-treatment/post-treatment/follow up) and caries was detected [40].

Observational studies

All three studies with observational designs (Table 1) were cross-sectional in nature [30, 31, 45]. The number of saliva cortisol measurements per day, and the time of the day varied among the studies. In all these studies, higher levels of salivary cortisol in children with caries disease were reported. One study showed that salivary cortisol levels of the mothers with children who had early childhood caries (ECC) were higher than the salivary cortisol levels of mothers who had children who were caries free [45].

Quality of reviewed studies

Quality assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 2. Based on the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool [37], the global quality rating of the three included studies was moderate [30, 31, 40] and of the three remaining studies was weak [43,44,45]. Most of the studies were compromised with sample selection strategy and did not provide sufficient information on the validity and reliability of the measurement methods used, the confounding factors or adjusting for confounders in analyses.

Discussion

In this scoping review, we systematically collected and examined the types and sources of scientific literature concerning the response of saliva to stress and its association with caries disease. This review focused on a broad range of possible stress-induced changes in salivary characteristics (e.g., changes in saliva flow rate, salivary proteins, immunoglobulins, cortisol, etc.), where only six studies measured saliva cortisol levels, as a measure of stress response. To control some confounders, studies with subjects who had chronic diseases/conditions (e.g., depression, cancer, etc.) and/or taking medications (e.g., antidepressants, corticosteroids, chemotherapy, radiation in the head and neck region) that may affect salivary function were excluded. Four out of six included studies (three cross-sectional and one quasi-experimental) found positive associations between saliva cortisol levels and caries while the other two studies reported no associations. Although this current review showed a possible positive association between salivary cortisol level as indicator of stress and dental caries, due to the small number of published literature and the methodological limitations of the included studies, our results do not permit to draw any firm conclusions. Yet, it identifies the knowledge gap and suggests that much remains to be done in this area of research.

According to the literature, numerous studies have reported changes in saliva composition and its properties after exposure to event-related stress [15, 23, 32, 33]. For instance, the increase in salivary protein concentration, as well as increase in secretory IgA concentration were found among young healthy adults (experimental stressors: public speech, laboratory exercise) [15, 23]. In addition, Bosh et al. [15] have reported that microbial colonization processes (adherence and co-adherence) were affected after event-related experimental stress, and these changes correlated with specific changes in salivary protein composition. Hugo et al. [16] have demonstrated that chronic psychological stress was associated with low stimulated saliva flow in adults. The absence of evidence on the aforementioned stress-induced changes in saliva and their association with caries may be explained by the following: 1. Dental caries is a multifactorial chronic disease and its causality investigation needs rigorous longitudinal study design, while the studies included in our review were quasi-experimental or cross-sectional in nature. 2. Most of the studies that revealed the changes in salivary composition were focusing on event-related stress and used experimental stressors. Thus, these studies were focusing on acute stress response while chronic response of saliva to stress may be different.

It is important to keep in mind a possible bi-directional association between stress and dental caries. Cohort study conducted in Dunedin, New Zealand has documented that dental fear in young adulthood was related to experience of high levels of dental caries and the tooth loss due to caries in mid- and late adolescence [46]. Thus, severe caries experience may be a co-adjuvant factor to chronic stress load.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

Many limitations should be kept in mind. Age, caries experience and saliva collection time were very variable in all the included studies. The methodological quality of included studies varied from weak to moderate. Most studies were compromised by study design, small study sample selection and sizes, measures and various methodological flaws (e.g., single point measurement of saliva cortisol, dental caries measurement criteria, blinding, non-random allocation, etc.). Despite the mentioned limitations, this scoping review was conducted systematically maintaining high quality in every step. Therefore, we could identify the existing knowledge gap in this area of research.

Future recommendations for research

In view of the importance attributed to this topic and the identified knowledge gap, there is a high need to investigate the potential role of stress in caries disease through well designed and rigorous prospective cohort studies. One of the research focus may be related to the understanding of physiological mechanisms by which chronic stress exposures, related to low socio-economic status adversities, interact with biological body systems and consequently affect factors directly related to dental caries, such as saliva characteristics and tooth biofilm. When measuring stress, multiple methods are recommended focusing on 1. the sources of stress, 2. perception and the affective response to stressors and 3. the physiological stress responses. Each of the afforested approaches assesses different components of stress process [46]. Saliva cortisol has been acknowledged as a reliable indicator for HPA axis reactivity during the acute stress induction in experimental settings [24, 27]. However, the use of saliva cortisol as a chronic stress indicator has some limitations because of its secretion variability during chronic stress [47]. In addition, since cortisol secretion depends on circadian rhythm, multiple time point sampling during the same day and over time are necessary to completely capture stress-induced cortisol response [27]. Furthermore, several factors such as age, sex, menstrual cycle, drugs, diseases, time lag, and salivary flow rate could confound study results and should be considered [48, 49]. Since assessment of saliva cortisol as physiological indicator of stress is associated with several measurement complications which can affect the outcome, the measurement of hair cortisol level may be used as alternative method that represent the physiological response of the body to chronic stress [50].

Conclusions

There is lack of evidence about an association between stress-related changes in saliva and caries. This study observed that more rigorous and analytical technics are needed for a precise measurement of saliva and tooth biofilm characteristics such as salivary proteome and oral biofilm microbiome analysis [51, 52]. Regarding the dental caries measurement methods, detailed caries diagnostic systems are recommended for use which consider severity and activity of caries lesions [53, 54]. In addition, a well-planned and rigorous cohort studies could provide better understanding of the role of stress in caries disease and would help generate new insights into the multifactorial etiology of dental caries. The combination of these approaches may provide strong evidence for a rational method of prevention/treatment of this worldwide disease.

Abbreviations

- ANS:

-

Autonomic nervous system

- CHU:

-

Center Hospitalier Universitaire

- CIHR:

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- ECC:

-

Early childhood caries

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica Database

- EPHPP:

-

Effective Public Health Practice Project

- FRQS:

-

Fonds de Recherche du Québec

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis

- IADR:

-

International Association for Dental Research

- IgA:

-

Immunoglobulin A

- IRSPUM:

-

Institut de Recherche en Santé Publique de l’Université de Montréal

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- PsycINFO:

-

Psychological Information Database

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WoS:

-

Web of Science

References

Edelstein BL, Chinn CH. Update on disparities in oral health and access to dental care for America’s children. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(6):415–9.

Kassebaum NJ, Bernabe E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):650–8.

Arrow P, Raheb J, Miller M. Brief oral health promotion intervention among parents of young children to reduce early childhood dental decay. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):245.

Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(9):661–9.

Bader JD, Rozier RG, Lohr KN, Frame PS. Physicians’ roles in preventing dental caries in preschool children: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(4):315–25.

Kay E, Locker D. Is dental health education effective? A systematic review of current evidence. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24(4):231–5.

Finlayson TL, Williams DR, Siefert K, Jackson JS, Nowjack-Raymer R. Oral health disparities and psychosocial correlates of self-rated oral health in the National Survey of American life. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S246–55.

Kim Seow W. Environmental, maternal, and child factors which contribute to early childhood caries: a unifying conceptual model. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22(3):157–68.

Duijster D, van Loveren C, Dusseldorp E, Verrips GH. Modelling community, family, and individual determinants of childhood dental caries. Eur J Oral Sci. 2014;122(2):125–33.

Nelson S, Lee W, Albert JM, Singer LT. Early maternal psychosocial factors are predictors for adolescent caries. J Dent Res. 2012;91(9):859–64.

Tang C, Quinonez RB, Hallett K, Lee JY, Kenneth Whitt J. Examining the association between parenting stress and the development of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(6):454–60.

Deinzer R, Granrath N, Spahl M, Linz S, Waschul B, Herforth A. Stress, oral health behaviour and clinical outcome. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10(Pt 2):269–83.

Hugo FN, Hilgert JB, Bozzetti MC, Bandeira DR, Gonçalves TR, Pawlowski J, de Sousa MLR. Chronic stress, depression, and cortisol levels as risk indicators of elevated plaque and gingivitis levels in individuals aged 50 years and older. J Periodontol. 2006;77(6):1008–14.

Sanders A, Slade G, Turrell G, Spencer A, Marcenes W. Does psychological stress mediate social deprivation in tooth loss? J Dent Res. 2007;86(12):1166–70.

Bosch JA, Turkenburg M, Nazmi K, Veerman EC, de Geus EJ, Amerongen AVN. Stress as a determinant of saliva-mediated adherence and coadherence of oral and nonoral microorganisms. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):604–12.

Hugo FN, Hilgert JB, Corso S, Padilha DM, Bozzetti MC, Bandeira DR, Pawlowski J, Goncalves TR. Association of chronic stress, depression symptoms and cortisol with low saliva flow in a sample of south-Brazilians aged 50 years and older. Gerodontology. 2008;25(1):18–25.

McEwen BS: Stress, definitions and concepts of. 2000.

McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Stress-and allostasis-induced brain plasticity. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:431–45.

McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: central role of the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):367–81.

Humphrey SP, Williamson RT. A review of saliva: normal composition, flow, and function. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;85(2):162–9.

Martins C, Buczynski AK, Maia LC, Siqueira WL, de Araujo Castro GFB. Salivary proteins as a biomarker for dental caries—a systematic review. J Dent. 2013;41(1):2–8.

Proctor GB, Carpenter GH. Regulation of salivary gland function by autonomic nerves. Auton Neurosci. 2007;133(1):3–18.

Bosch JA, Brand HS, Ligtenberg TJ, Bermond B, Hoogstraten J, Amerongen AVN. Psychological stress as a determinant of protein levels and salivary-induced aggregation of Streptococcus gordonii in human whole saliva. Psychosom Med. 1996;58(4):374–82.

Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):434–45.

Gomes HS, Vieira LA, Costa PS, Batista AC, Costa LR. Professional dental prophylaxis increases salivary cortisol in children with dental behavioural management problems: a longitudinal study. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16(1):74.

Milsom K, Tickle M, Humphris G, Blinkhorn A. The relationship between anxiety and dental treatment experience in 5-year-old children. Br Dent J. 2003;194(9):503.

Allen AP, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Biological and psychological markers of stress in humans: focus on the Trier Social Stress Test. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;38:94–124.

Chiodini I, Adda G, Scillitani A, Coletti F, Morelli V, Di Lembo S, Epaminonda P, Masserini B, Beck-Peccoz P, Orsi E, et al. Cortisol secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes: relationship with chronic complications. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(1):83–8.

Pereg D, Gow R, Mosseri M, Lishner M, Rieder M, Van Uum S, Koren G. Hair cortisol and the risk for acute myocardial infarction in adult men. Stress. 2011;14(1):73–81.

Boyce WT, Den Besten PK, Stamperdahl J, Zhan L, Jiang Y, Adler NE, Featherstone JD. Social inequalities in childhood dental caries: the convergent roles of stress, bacteria and disadvantage. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(9):1644–52.

Barbosa T, Castelo P, Leme M, Gaviao M. Associations between oral health-related quality of life and emotional statuses in children and preadolescents. Oral Dis. 2012;18(7):639–47.

Naumova EA, Sandulescu T, Al Khatib P, Thie M, Lee W-K, Zimmer S, Arnold WH. Acute short-term mental stress does not influence salivary flow rate dynamics. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51323.

Naumova EA, Sandulescu T, Bochnig C, Al Khatib P, Lee WK, Zimmer S, Arnold WH. Dynamic changes in saliva after acute mental stress. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4884.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48.

National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University; 2008. (Updated 03 October, 2017) Retrieved from http://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84.

Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):12–8.

Yfanti K, Kitraki E, Emmanouil D, Pandis N, Papagiannoulis L. Psychometric and biohormonal indices of dental anxiety in children. A prospective cohort study. Stress. 2014;17(4):296–304.

Organization WH. World Health Organization: oral health surveys, basic methods. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997.

Koch G. Selection and caries prophylaxis of children with high caries activity. One-year results. Odontol Revy. 1970;21(1):71–81.

Kambalimath HV, Dixit UB, Thyagi PS. Salivary cortisol response to psychological stress in children with early childhood caries. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21(2):231–7.

Rai K, Hegde AM, Shetty S, Shetty S. Estimation of salivary cortisol in children with rampant caries. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2010;34(3):249–52.

Pani SC, Abuthuraya D, Alshammery HM, Alshammery D, Alshehri H. Salivary cortisol as a biomarker to explore the role of maternal stress in early childhood caries. Int J Dent. 2013;2013:565102.

Vanaelst B, De Vriendt T, Huybrechts I, Rinaldi S, De Henauw S. Epidemiological approaches to measure childhood stress. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(3):280–97.

Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. In: American Psychological Association; 2007.

Jessop DS, Turner-Cobb JM. Measurement and meaning of salivary cortisol: a focus on health and disease in children. Stress. 2008;11(1):1–14.

Hellhammer DH, Wüst S, Kudielka BM. Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(2):163–71.

Russell E, Koren G, Rieder M, Van Uum S. Hair cortisol as a biological marker of chronic stress: current status, future directions and unanswered questions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(5):589–601.

Lee YH, Zimmerman JN, Custodio W, Xiao Y, Basiri T, Hatibovic-Kofman S, Siqueira WL. Proteomic evaluation of acquired enamel pellicle during in vivo formation. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67919.

Dige I, Gronkjaer L, Nyvad B. Molecular studies of the structural ecology of natural occlusal caries. Caries Res. 2014;48(5):451–60.

Nyvad B, Machiulskiene V, Bælum V. Reliability of a new caries diagnostic system differentiating between active and inactive caries lesions. Caries Res. 1999;33(4):252–60.

Pitts N. “ICDAS”--an international system for caries detection and assessment being developed to facilitate caries epidemiology, research and appropriate clinical management. Community Dent Health. 2004;21(3):193.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Mr. Martin Morris (librarian, McGill University) for the design of the search strategy.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Institute de Recherché en Santé Publique de l’Université de Montréal (IRSPUM), for supporting this work through providing 2-year postdoctoral scholarship to Dr. S. Tikhonova. Dr. E. Emami holds a clinician-scientist Awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Fonds de recherche du Québec Santé (FRQ-S). The research allocations through these funds were used for supporting this work. The funding agencies did not play any role in the study design, data gathering, data analysis and interpretation, the manuscript writing.

Availability of data and materials

Data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed extensively to the work presented in this manuscript. ST, LB, EE and WS contributed to the conception and design of the study. ST and VS performed data acquisition. ST, LB, EE performed data analysis and interpretation. VS and KC revised the data analysis and data interpretaion. ST, LB, VS and EE were contributors in writing the manuscript. All the co-authors critically reviewed the manuscript, read and approved its final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Search strategy example, MEDLINE

1. exp. Saliva/.

2. exp. Salivary Proteins/ and Peptides/.

3. “Salivary Proteins and Peptides”.nm.

4. saliva*.mp.

5. or/1–4.

6. exp. Dental Caries/.

7. exp. Dental Caries Susceptibility/.

8. caries*.mp.

9. white spot*.mp.

10. ((tooth or teeth) adj5 decay*).mp.

11. carious.mp.

12. or/6–11.

13. 5 and 12.

14. Stress, Physiological/.

15. exp. Stress, Psychological/.

16. exp. Anxiety/.

17. exp. Depression/.

18. stress*.tw.

19. (anxiet* or anxious*).tw.

20. depression.tw.

21. anguish*.tw.

22. or/14–21.

23. 13 and 22.

24. 5 and 13 and 22.

25. limit 24 to (yr = “1960 -Current” and (english or french)).

26. limit 25 to humans.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tikhonova, S., Booij, L., D’Souza, V. et al. Investigating the association between stress, saliva and dental caries: a scoping review. BMC Oral Health 18, 41 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0500-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0500-z