Abstract

Background

Insulinoma is an uncommon insulin-secreting neuroendocrine tumor that presents with severe recurrent hypoglycemia. Although cases of extrapancreatic insulinomas have been reported, the majority of insulinomas occur in the pancreas. The number of reported cases of ectopic insulinomas with follow-up assessments is limited and they do not report disease recurrence. The current report presents the first documented case of recurrent extrapancreatic insulinoma with 8 years of follow-up, provides relevant literature review, and proposes surveillance and treatment strategies.

Case presentation

We describe an insulinoma localized in the duodenal wall of a 36-year-old female who presented in 2013 with weight gain and Whipple’s triad and was successfully managed with duodenotomy and enucleation. She presented again in 2017 with recurrent Whipple’s triad and was found to have metastatic disease localized exclusively to peripancreatic lymph nodes. Primary pancreatic insulinoma was not evident and her hypoglycemia resolved following lymph node dissection. Eight years after initial presentation continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) showed a trend for euglycemia, and PET-CT Gallium 68 DOTATATE scan evaluation indicated absence of recurrent disease.

Conclusion

Insulinomas are rare clinical entities and extrapancreatic insulinomas are particularly uncommon. Follow-up evaluation and treatment strategies for ectopic insulinoma recurrence presents a significant clinical challenge as the condition has hitherto remained undescribed in the literature. Available evidence in the literature indicates that lymph node metastases of intrapancreatic insulinomas likely do not change prognosis. Given the absence of long-term data informing the management and monitoring of patients with extrapancreatic insulinoma, we suggest patient education for hypoglycemic symptoms, monitoring for hypoglycemia with CGM, annual imaging, and a discussion with patients regarding treatment with octreotide or alternative somatostatin receptor analog therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Insulinoma is a rare neuroendocrine tumor (NET) with an incidence of 0.4 cases per 100,000 per year, and is typically seen in the 5th decade of life with a slight predominance of the female sex [1]. The vast majority of these cases (> 85%) are benign and almost all occur within the pancreatic parenchyma; however, ectopic insulinomas have previously been described in the duodenum [2], duodenohepatic ligament [3], kidney [4], appendix [5], spleen [6], perisplenic tissue [7], and adjacent to the ligament of Treitz [8]. Each of these extrapancreatic insulinoma cases was successfully managed with surgery, but the longest recurrence-free follow-up time described was only 3 months with no further reported follow-up assessment.

In the current report, we describe a 36-year-old female who presented with a primary insulinoma in the wall of the second portion of the duodenum that was surgically managed with resolution of her hypoglycemia. She then presented 4 years later with recurrent hypoglycemia and localized peripancreatic lymph node disease. We provide 8-year follow-up results and discuss strategies for follow-up evaluation, surveillance, and management of recurrent, metastatic extrapancreatic insulinoma.

Case presentation

In June 2013, a 36-year-old female presented with Whipple’s triad (documented, symptomatic hypoglycemia that responded to glucose) and weight gain of 40 pounds. Her serum glucose level was 49 mg/dL (normal range: 70–99 mg/dL) with inappropriately elevated insulin level of 8.1 μIU/mL (normal range: 2.6–24.9 μIU/mL) and C-peptide level of 2.2 ng/mL (normal range: 1.1–4.4 ng/mL) prior to receiving dextrose. A 72-hour fast confirmed hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia at 26 hours (glucose 36 mg/dL, insulin 10.3 mIU/L [normal range: 2.6–25 mIU/L], proinsulin 21.7 pmol/L [normal range: ≤21.7 pmol/L], C-peptide 2.3 μg/dL [normal range: 1.1–4.4 μg/dL], beta hydroxybutyric acid 0.06 mmol/L [normal range: 0.02–0.27 mmol/L], negative sulfonylurea screen, cortisol 28.9 μg/dL [normal range 6.2–19.4 μg/dL]). Serum calcium level was 8.8 mg/dL [normal range: 8.6–10.2 mg/dL] and parathyroid hormone level was 54 pg/mL [normal range: 10–65 pg/mL].

Abdominal CT with intravenous contrast showed a 1.1 cm × 1.6 cm × 2 cm hypervascular mass in the second portion of the duodenum without obstruction and a normal pancreas. OctreoScan did not show uptake in the area of the mass. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy identified a mass in the duodenal sweep and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) showed a 1.6 cm × 1.6 cm duodenal mass (Fig. 1) with 3 hypoechoic well-defined lymph nodes distal to the mass measuring up to 1 cm in length. She underwent exploratory laparotomy with duodenotomy and NET enucleation in August 2013. Histopathology showed a well-differentiated intermediate grade 1.5 cm NET with Ki-67 index of 3–4%. All 4 of the 4 resected lymph nodes were negative for disease. Following surgery, she experienced weight loss of 30 pounds and denied any symptoms of hypoglycemia at her 6-month follow-up evaluation. The patient’s family history was negative for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) syndrome, endocrine tumors or abnormalities of calcium metabolism, and her personal history was negative for nephrolithiasis or associated MEN-1 conditions. The patient’s calcium, parathyroid hormone, and prolactin levels were normal. MEN-1 testing was discussed with the patient but was not pursued at the time.

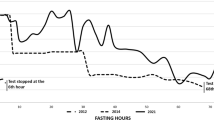

In September 2015 she reported hypoglycemia symptoms during exercise, and random glucose meter checks confirmed blood glucose levels ranging 60–70 mg/dL during these episodes. Seven-day continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) showed no glucose values < 60 mg/dL, and CT of the abdomen with intravenous contrast did not show evidence of disease. In 2015, Ga-68-DOTATATE imaging was not yet available at our institution to allow for further imaging evaluation.

In July 2017 the patient’s hypoglycemic symptoms returned with increasing frequency. Placement of another 7-day CGM showed that 29% of glucose values were < 60 mg/dL and revealed a pattern of nocturnal hypoglycemia. Abdominal CT evaluation did not show evidence of disease. PET-CT with Ga68-DOTATATE showed a 1.5 cm × 1.3 cm soft tissue nodule adjacent to the inferior pancreatic head and wall of the 2nd portion of the duodenum with maximum standardized uptake value (SUV) of 41 (Fig. 2). Repeated 72-hr fast was deemed unnecessary. EUS showed normal duodenum and pancreas but found peripancreatic lymphadenopathy. Lymph node fine-needle aspiration confirmed NET. Repeat surgery found metastatic, well-differentiated NET in 5 of 12 lymph nodes with a Ki-67 index of 3.8%. Insulin staining was not performed on the resected lymph nodes. Hypoglycemia resolved after surgery. Follow-up Ga68-DOTATATE scan in January 2018—4.5 years after her initial presentation—did not show evidence of disease. As of June 2021, she reported feeling well and CGM showed 99% time-in-range (blood glucose 70–180 mg/dL), with < 1% hypoglycemia over a 2-week period. Ga68-DOTATATE scan in 2020 showed small focus of uptake at the root of mesentery but was deemed possible overcall. Follow-up Ga68-DOTATATE scan in November 2021 showed no evidence of somatostatin receptor positive neoplasm, and diagnostic CGM is currently scheduled to occur every 3 months. Table 1 below is a summary of the patient’s history.

Discussion

Insulinoma is a rare tumor resulting in insulin hypersecretion. Patients with insulinoma present with neuroglycopenic symptoms such as confusion and seizure as well as occasional diaphoresis, anxiety, palpitations, and tremors. The majority of insulinomas are small (< 2 cm), single, sporadic, and arise within the pancreas with equal intra-organ distribution [1, 9, 10]. Ectopic insulinomas have also been described in the literature and have been reported to account for an estimated incidence of 1–2% of all insulinomas [11].

Ectopic insulinomas usually develop in ectopic pancreatic tissue and have been reported in 0.5–15% of autopsies as well as in 1 out of 500 abdominal surgeries [8]. In our patient, careful review of the initial resection specimen showed no evidence of adjacent ectopic pancreatic tissue.

A population-based study of 224 patients with surgically confirmed insulinomas presenting between 1927 and 1986 showed recurrence rates of 7% in patients with sporadic insulinomas compared with 21% in patients with MEN syndrome type 1 [12]. Recurrence of pancreatic insulinoma can develop 4–20 years after initial surgery [1], but there have not been reports of disease recurrence for extrapancreatic insulinomas. Also, previous cases of extrapancreatic insulinoma did not include significant follow-up evaluations as each respective patient was presumably cured surgically [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The longest follow-up evaluation reported among these cases was 4 months in the setting of a surgically-managed ectopic neuroendocrine tumor arising from the ligament of Treitz [8]. As our case seems to be the first recurrence of extrapancreatic insulinoma, the future surveillance and management of our patient remains a challenge Table 2.

In patients with a biochemical diagnosis of insulinoma, surgical cure rates range from 77 to 100%. When technically possible, tumor enucleation is preferred. For tumors not amenable to enucleation, various surgical techniques can be pursued, such as segmental resection of the pancreas, distal pancreatectomy, or pancreaticoduodenectomy [16]. Complications associated with surgery include pancreatic fistula, pseudocyst, intra-abdominal abscess, pancreatitis, hemorrhage, and diabetes. For patients who are not surgical candidates or are awaiting surgical intervention, medical therapy and dietary modifications are important interventional measures. These include diazoxide or long-acting somatostatin analogs such as octreotide and lanreotide. Endoscopically directed ethanol ablation has been utilized in refractory individuals who are not surgical candidates, but this approach is not considered to be standard of care in healthier patients [17]. Typically, short-acting octreotide is initiated to assess for tolerability and side effects, and, if tolerated, can be transitioned to long-acting somatostatin analog therapy.

Malignant insulinomas are those that show evidence of local invasion into surrounding soft tissue or distant metastases to the liver or lymph nodes. The 10-year survival for malignant insulinomas is reported to be 29% [18]. Aggressive surgical resection including pancreatic resection is considered first-line surgical treatment in the setting of malignant insulinomas. Liver resection and even liver transplantation have been attempted to improve patient survival if hepatic metastases are present. When surgical interventions are not feasible, alternative debulking procedures such as radiofrequency thermoablation, cryotherapy, hepatic artery embolization and chemoembolization can be attempted; such options provide good but temporary palliation [19]. For patients with highly proliferating, rapidly progressing, or symptomatic insulinomas, chemotherapy may produce greater tumor size reduction compared with somatostatin analogues.

Everolimus, an oral mTOR inhibitor, has been used for malignant insulinomas associated with refractory hypoglycemia [20]. The exact mechanism by which everolimus can control hypoglycemia in patients with insulinoma is not fully elucidated, but mechanisms proposed include increasing peripheral insulin resistance as well as decreasing beta-cell proliferation, survival and metabolism [21]. Peptide receptor radiotherapy (PRRT), which uses radiolabeled somatostatin analogues to target specific peptide receptors on tumor cells is another treatment option being used in inoperable locoregional or distant metastatic gastreoenteropanceratic NETs [22]. 177Lu-labeled PRRT is currently the radionuclide of choice. PRRT for high-grade gastroenteropancreatic NETs has shown promising response rates, disease control rates, progression free survival, and overall survival [23]. In patients with metastatic insulinoma, PRRT is also effective in controlling hypoglycemia even in the setting of tumor regrowth [24]. New agents under investigation as treatment options for malignant insulinomas associated with refractory hypoglycemia include anti-insulin receptor monoclonal antibodies [25], oral somatostatin receptor drugs, and soluble stable glucagon [26].

As improvements in imaging studies continue to increase the frequency of pancreatic NET detection, recent studies have also evaluated the role of lymph node metastases in prognosis and management strategies. A retrospective review found tumor location, tumor size, Ki-67 index, and presence of lymphovascular invasion were associated with lymph node metastasis. Tumor diameter > 1.5 cm, tumors located in the head of pancreas, presence of lymphovascular invasion on surgical pathology, and Ki-67 index > 20% were reported to frequently present with lymph node metastasis [27]. Further analysis in this study showed that lymph node metastasis was significantly associated with a decrease in disease-free survival (4.5 years compared with 14.6 years for patients without lymph node metastasis). At this time, multiple studies report that both the number and presence of positive lymph nodes have important prognostic value in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, thereby supporting the recommendation for systematic removal of lymph nodes in the peritumoral area during any pancreatic NET operation [28]. Patients with duodenal NETs treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy have been reported to have a higher incidence of metastasis to locoregional lymph nodes compared with patients with pancreatic NETs. In a study investigating surgical outcomes of patients with pancreatic versus duodenal NETs, those with duodenal NETs had more lymph node metastases. Yet, despite this difference in metastases, there was no impact on recurrence-free survival or overall survival between the two groups. Furthermore, those with duodenal NETs were more likely to have recurrent disease within 2 years of pancreaticoduodenectomy compared with those with pancreatic NETs. Further analysis is required to determine if these outcomes are similar in patients presenting with insulinomas. If so, this may suggest that a duodenal primary NET has higher malignant potential than a typical pancreatic primary NET [29].

At the present time, our patient continues to do well clinically with no evidence of significant hypoglycemia. She has declined octreotide treatment due to concerns with side effects and wishes to continue active surveillance with imaging. Given her recurrence of hypoglycemic symptoms and evidence of lymph node metastases 2 years after initial enucleation surgery, we suspect that she has microscopic, undetectable, clinically silent disease. As such, we will continue to monitor her closely for redevelopment of hypoglycemia.

Conclusion

Extrapancreatic insulinomas are rare and the few cases of the tumors described in the literature do not report long-term follow-up assessment. This report presents the first known case of an extrapancreatic insulinoma recurrence and the longest reported followup. Current evidence shows that lymph node metastases of intrapancreatic insulinomas likely do not change prognosis. It is unclear if this is applicable to extrapancreatic insulinomas as well. More long-term outcome data are necessary to help determine how these patients should be monitored and managed. To monitor and manage extrapancreatic insulinoma recurrence we suggest patient education for hypoglycemic symptoms, monitoring for hypoglycemia with continuous glucose monitoring, annual imaging, and an ongoing discussion with patient regarding treatment with octreotide or alternative somatostatin receptor analog therapies.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed.

Abbreviations

- NET:

-

Neuroendocrine tumor

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasound

- MEN-1:

-

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1

- CGM:

-

Continuous glucose monitoring

- SUV:

-

Standardized uptake value

- PRRT:

-

Peptide receptor radiotherapy

References

Iglesias P, Diez JJ. Management of endocrine disease: a clinical update on tumor-induced hypoglycemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(4):R147–57. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-13-1012.

La Rosa S, Pariani D, Calandra C, et al. Ectopic duodenal insulinoma: a very rare and challenging tumor type. Description of a case and review of the literature. Endocr Pathol. 2013;24(4):213–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-013-9262-y.

Xian-Ling W, Yi-Ming M, Jing-Tao D, et al. Successful laparoscope resection of ectopic insulinoma in duodenohepatic ligament. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341(5):420–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31820b8a67.

Ramkumar S, Dhingra A, Jyotsna V, et al. Ectopic insulin secreting neuroendocrine tumor of kidney with recurrent hypoglycemia: a diagnostic dilemma. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6823-14-36.

Lombardi M, Battezzati MA, Grosso F, Muni A, Volante M, Ansaldi E. Appendix insulin secreting neuroendocrine tumor in a diabetic patient: A challenging diagnosis. Journal of systems and integrative Neuroscience. 2016;2(3). https://doi.org/10.15761/jsin.1000128.

Cárdenas CM, Domínguez I, Campuzano M, et al. Malignant insulinoma arising from intrasplenic heterotopic pancreas. Jop. 2009;10(3):321–3.

Yoshikawa K, Wakasa H. Hypoglycemia associated with aberrant insulinoma: a case report of 16 years follow-up. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1980;132(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.132.17.

Hennings J, Garske U, Botling J, Hellman P. Malignant insulinoma in ectopic pancreatic tissue. Dig Surg. 2005;22(5):377–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000090998.

Sotoudehmanesh R, Hedayat A, Shirazian N, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) in the localization of insulinoma. Endocrine. 2007;31(3):238–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-007-0045-4.

Crippa S, Zerbi A, Boninsegna L, et al. Surgical management of insulinomas: short- and long-term outcomes after enucleations and pancreatic resections. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):261–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.1843.

Oberg K, Eriksson B. Endocrine tumours of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19(5):753–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2005.06.002.

Service FJ, McMahon MM, O'Brien PC, Ballard DJ. Functioning Insulinoma—incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival of patients: A 60-year study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66(7):711–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62083-7.

Zhang X, Jia H, Li F, et al. Ectopic insulinoma diagnosed by 68Ga-Exendin-4 PET/CT: A case report and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(13):e25076. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000025076.

Wang M, Vasey Q, Varikatt W, McLean M. Ectopic insulin secretion by a large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix. Clinical Case Reports. 2021;9(1):482–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.3562.

Garg R, Memon S, Patil V, Bandgar T. Extrapancreatic insulinoma. World J Nucl Med. 2020;19(2):162–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/wjnm.WJNM_41_19.

Shin JJ, Gorden P, Libutti SK. Insulinoma: pathophysiology, localization and management. Future Oncol. 2010;6(2):229–37. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon.09.165.

Kittah NE, Vella A. Management of Endocrine Disease: pathogenesis and management of hypoglycemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(1):R37–r47. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje-16-1062.

Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Sumiyoshi T, et al. Diagnosis and management of insulinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(6):829–37. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.829.

de Herder WW, Niederle B, Scoazec JY, et al. Well-differentiated pancreatic tumor/carcinoma: insulinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84(3):183–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000098010.

Bernard V, Lombard-Bohas C, Taquet MC, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in patients with metastatic insulinoma and refractory hypoglycemia. Eur J Endocrinol May 2013;168(5):665–674. doi:https://doi.org/10.1530/eje-12-1101.

Davi MV, Pia A, Guarnotta V, Pizza G, Colao A, Faggiano A. The treatment of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycaemia in adults: an update. J Endocrinol Investig Jan 2017;40(1):9–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-016-0536-3.

Hicks RJ, Kwekkeboom DJ, Krenning E, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for the standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with Radiolabelled somatostatin analogues. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105(3):295–309. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475526.

Sorbye H, Kong G, Grozinsky-Glasberg S. PRRT in high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (WHO G3). Endocr Relat Cancer. 2020;27(3):R67–77. https://doi.org/10.1530/erc-19-0400.

De Herder WW, Van Schaik E, Kwekkeboom D, Feelders RA. New therapeutic options for metastatic malignant insulinomas. Clin Endocrinol. 2011;75(3):277–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04145.x.

Corbin JA, Bhaskar V, Goldfine ID, et al. Inhibition of insulin receptor function by a human, allosteric monoclonal antibody: a potential new approach for the treatment of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. MAbs. 2014;6(1):262–72. https://doi.org/10.4161/mabs.26871.

Hawkes CP, De Leon DD, Rickels MR. Novel preparations of glucagon for the prevention and treatment of hypoglycemia. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(10):97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1216-4.

Hashim YM, Trinkaus KM, Linehan DC, et al. Regional lymphadenectomy is indicated in the surgical treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs). Ann Surg. 2014;259(2):197–203. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000000348.

Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the Management of Patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):153–71. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443171.

Dong DH, Zhang XF, Lopez-Aguiar AG, et al. Surgical outcomes of patients with duodenal vs pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors following pancreatoduodenectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122(3):442–9.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the patient for supporting this manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding provided for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DCM, CAS, VS, VC, DF, and AA were involved in the diagnostic workup and care of the patient. VC performed EUS. DF performed enucleation. MW and VS wrote the manuscript. All authors provided feedback and comments on the final manuscript. AA supervised all stages of manuscript development. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent to publish has been obtained from the patient in this case report. A copy of the consent form is available for the Editor to review upon request.

Competing interests

David C. Metz is a consultant to Crinetics, Curium, and AAA. For the rest of the authors, none were declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Walker, M.P., Shenoy, V., Metz, D.C. et al. Case presentation of 8-year follow up of recurrent malignant duodenal Insulinoma and lymph node metastases and literature review of malignant Insulinoma management. BMC Endocr Disord 22, 310 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-01219-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-01219-9