Abstract

Background

Primary nasopharyngeal lymphoma (NPL) is a very rare tumor of Waldeyer ring (WR) lymphoid tissue. It is challenging to differentiate lymphoma infiltration of pituitary from a pituitary adenoma, meningioma infiltration, and other sellar lesions to plan a suitable treatment strategy. We presented for the first time a unique case of NPL with an unusual presentation of oculomotor nerve palsy associated with pan-pituitary involvement in a diabetic patient.

Case presentation

A 64-year old diabetic woman with no previous history of malignancy presented with intermittent diplopia for about the last nine months. Severe headache, left eye ptosis and hypoglycemic episodes were added to her symptoms after a while. Further complaints include generalized weakness, loss of appetite, generalized musculoskeletal pain, and 6–7 kg weight loss within six months. Her family history was unremarkable. Physical examinations of eyes indicated left eye 3rd, 4th, and 6th nerve palsy. But, she was not anisocoric, and the pupillary reflexes were normal on both eyes. No lymphadenopathy, organomegaly and other abnormalities were found. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a heterogeneous enhancement in the seller and suprasellar regions, enlargement of the stalk, parasellar dural enhancement and thickening of the sphenoid sinus without bone erosion. Also, both cavernous sinuses were infiltrated and both internal carotid arteries were encased by the neoplastic lesion. It suggested an infiltrative neoplastic lesion which compressed the cranial nerves. Pituitary hormone levels assessment indicated a pan-hypopituitarism. Following nasopharyngeal mucosal biopsy, the immunohistochemistry (IHC) findings revealed a low-grade non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma. Systemic workup, including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies, bone marrow aspiration, chest and abdominopelvic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) indicated no other involvement by the lymphoma. After chemotherapy courses, central adrenal insufficiency, partial central diabetes incipidious (CDI) and central hypothyroidism have been resolved. To our best knowledge, we found 17 cases of NPL with cranial nerve palsy, 1 case of NPL with pan-hypopituitarism and no NPL case with both cranial nerve palsy and pituitary dysfunction.

Conclusions

The incidence of cranial neuropathy in patients with diabetes should not merely be attributed to diabetic neuropathy without further evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nasopharyngeal lymphoma (NPL) is a rare malignancy with extranodal lymphoid proliferation [1]. NPL is classified into Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). NHL lymphoma accounts for 86 to 90% of all lymphoma cases [2, 3]. Lymphoid tissues of the palatine tonsils, soft palate, nasopharynx, oropharyngeal wall, and base of the tongue is known as the Waldeyer’s ring [1]. Previous studies have indicated that less than 10–18% of NHL cases involve the Waldeyer’s ring [1, 4], which about 35–37% of them were at the nasopharyngeal site [1]. In most cases, NPL appears with nasal manifestations, including epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and purulent rhinorrhea. However, it can present with a neck mass, headache, and B symptoms (i.e., weight loss, night sweats, and fever), less commonly [5].

On the other hand, 10–15% of intracranial neoplasms were attributed to pituitary tumors [6]. It has been reported that pituitary adenoma and meningioma are the most common tumors which can involve the pituitary gland. However, it is a rare site for diffuse malignant disease and metastasis [7]. The pituitary gland can be involved by metastatic lesions via the skull base, hematogenous, or meningeal spread [8]. According to a recent systematic review, the pituitary metastases (PM) are uncommon, accounting for 0.4% of intracranial metastases [9]. Almost every cancer is reported having a potential source for sellar metastasis. Lung and breast neoplasms are responsible for two-thirds of PM. The frequency of NHL involving the hypothalamus-pituitary axis is < 0.5% among PM [10]. A systematic review in 2015 stated that the most common symptom among all reported PM cases is diabetes insipidus. Anterior hypopituitarism (39.66%), visual deterioration (41.38%), cranial nerve palsies (41.38%) and headaches (32.76%) were the other symptoms which were reported. As symptomatic PM can be closely mimic a pituitary adenoma, the presentations of diabetes insipidus and/or cranial neuropathies could suggest PM rather than pituitary adenoma, especially in a rapidly developed courses, and in patients over 50 years old. Moreover, some studies have suggested that the presence of bony erosion without sellar enlargement indicates PM more than a pituitary adenoma [11]. PM has a poor prognosis and the management of patients with PM is palliative. The diagnosis of such malignancies is challenging because patients mostly presented nonspecific signs that could overshadow symptoms of hypopituitarism or diabetes insipidus, so the diagnosis is ultimately confirmed by histopathology [9, 12]. Sellar masses are rarely constituted by infiltrative neoplasm (such as lymphoma), inflammatory and granulomatous diseases of the pituitary [13]. Therefore, in a patient with lymphoma, it is essential to differentiate lymphoma infiltration of the pituitary from benign lesions to plan an appropriate treatment strategy.

Case presentation

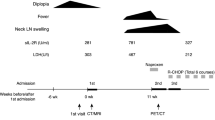

A 64-year old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus for more than thirty years and no previous history of malignancy presented with intermittent diplopia for about the last nine months, especially while going down the stairs. Diplopia was gradually increasing frequency and intensity in the previous few months. During the previous two months, the patient developed a severe headache, left eye ptosis, and hypoglycemic episodes. Further complaints include generalized weakness, loss of appetite, generalized musculoskeletal pain, and 6–7 kg weight loss within six months. Her hemoglobin A1C levels were around 7% in prior visits. Her family history was unremarkable.

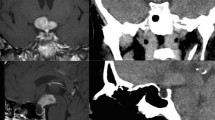

In our initial physical examinations, she was obese (body mass index =34 kg/m2), and her blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg. No lymphadenopathy and organomegaly were found. No other abnormalities were noted on physical examinations except for left eye ptosis (3rd, 4th, and 6th nerve palsy). But, she was not anisocoric, and the pupillary reflexes were normal on both eyes. The pupils were round and equal and reacted to light consensually and directly. Visual acuity was normal in both eyes. The other examinations of cranial nerves were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hypothalamus and pituitary indicated a heterogeneous enhancement of the sellar and suprasellar regions, enlargement of the stalk, parasellar dural enhancement with the involvement of both cavernous sinuses and internal carotid arteries, and thickening of the sphenoid sinus without any bone erosion. It was not possible to differentiate between pituitary tumor and infiltrated nasopharyngeal region. It suggested an infiltrative neoplastic lesion that compressed left III, IV and VI cranial nerves. Also, the thickening of the sphenoid sinuses and nasopharyngeal regions was seen (Fig. 1).

Complete blood cell testing showed leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. As per whole blood count, red blood cell (RBC) and platelet counts were 4.69 Mil/ mm3 and 88,000/mm3, respectively. Also, white blood cell count (WBC) was 3100/mm3 (consist of 44% lymphocytes, 45% neutrophils, 8.7% monocyte, 1.6% eosinophil and 0.7% basophil). Hemoglobin and hematocrit were 12.9 g/dl and 37.6%, respectively.

To evaluate the patient for infiltrative disease, i.e., lymphoma, sarcoidosis, and tuberculosis, we tested serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels, which were reported in the normal range (LDH: 353 (230–460 U/L) and ACE: 51.1(8–52 U/L)). Also, the purified protein derivative (PPD/tuberculin) test was negative.

To rule out immunological diseases that could infiltrate cavernous sinuses and pituitary gland area (e.g., Wegener’s granulomatosis, Ig G4 related disease), immunologic assays were done. All serum immunology assays except perinuclear anti-neutrophil antibodies (P-ANCA or anti-MPO) were within their reference values i.e. immunoglobulin G (IgG): 1055 (700–1600 mg/dL), Ig A: 208 (70-400 mg/dL), Ig M: 45 (40–230 mg/dL), Cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil antibodies (C-ANCA or Anti-PR3): 4.9 (Negative: < 10 U/mL), and IgG4: 550.3 (39–864 mg/L). The result of P-ANCA was 23.5 U/mL (Negative: < 10). The bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed according to bi-cytopenia that showed cellular marrow without atypia.

Laboratory evaluation of hypothalamic and pituitary axis revealed a pan-hypopituitarism i.e. free T4: 0.6 (0.7–2.5 ng/dL), free T3: 0.18 (0.2–0.5 ng/dL), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): 0.47 (0.3–4.2 μIU/mL), cortisol at 8 am: 3 (5–23 μg/dL), adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH): 24.78 (7.2–64 pg/mL), luteinizing hormone (LH): 1.2 (8.2–40.8 IU/L), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH): 5.3 (35–153 IU/L), prolactin: 9.7 (2.1–17.7 ng/mL), and insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1): 24 (33–220 ng/mL).

In cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analyses, protein and LDH were elevated (Table 1). CSF cytology examination showed a few small lymphoid cells with irregular nuclei.

Pathologic findings of tissue biopsy of thickened nasopharyngeal mucosa reported a low-grade lymphoma. Cell immunohistochemistry (IHC) were positive for CD20 and Bcl-2 in most lymphoid cells (B-cells). Moreover, CD3 and CD5 were positive, and CD10 was negative in some lymphoid cells (T-cells). Also, CD-23 and cyclin D1 were negative, and cell proliferation index Ki-67 was about 10%. These findings revealed a low-grade B-cell lymphoma (Fig. 2).

Chest and abdominopelvic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) indicated no abnormalities and lymphadenopathy. So we concluded that the final diagnosis for the current patient was a primary lymphoma originated from the nasopharyngeal mucosa by spreading the upwards areas, including both cavernous sinuses, sellar, and suprasellar regions.

She received six courses of chemotherapy with CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and dexamethasone plus Rituximab. Oral prednisolone (7.5 mg daily) and levothyroxine (50 μg daily) were prescribed simultaneously with chemotherapy, due to her pan-hypopituitarism. A few days after prednisolone usage, ptosis dramatically improved. MRI enhancement in the sellar and suprasellar regions and both cavernous sinuses were largely eliminated after the last chemotherapy course (Fig. 3). Besides, hematological defects were improved significantly.

One month after treatment with prednisolone, the patient complained about polyuria and nocturia. Partial central diabetes insidious (CDI) was diagnosed based on more than 3 l 24-h urine volume, mild hypernatremia (Na: 147 meq/L) and low urine osmolality (urine specific gravity was 1.005 whereas the urine specific gravity in the first evaluation was 1.010). After chemotherapy courses central adrenal insufficiency, partial CDI and central hypothyroidism have been resolved.

Search strategy for literature review

We searched PubMed for articles published from Jan 1, 1990, to Aug 1, 2020, using the search terms “nasopharyngeal lymphoma”, “non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the nasopharynx”, “nasopharyngeal B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma”, “nasopharyngeal Hodgkin’s disease” in combination with the terms “pan-hypopituitarism”, “pituitary dysfunction”, “cranial nerves palsy”, “multiple cranial nerve palsy”, “oculomotor nerve palsy”, “isolated oculomotor nerve palsy”, “multiple cranial nerve dysfunction”,” III cranial nerve palsy”, “IV cranial nerve palsy”, “VI cranial nerve palsy”, “third cranial nerve palsy”,“4th cranial nerve palsy”,“6th cranial nerve palsy”. Articles published in English were included. We focused mostly on articles from case reports or case series.

Discussion and Conclusions

We have described a woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus and nasopharyngeal B-cell lymphoma infiltration of both cavernous sinuses and pituitary gland, who presented with the left eye ptosis (3rd, 4th, and 6th nerve palsy), severe headache, and pan-hypopituitarism.

Clinical presentations in our patient (i.e., hypopituitarism, headaches, and visual disturbances) could suggest the infiltration of the pituitary gland by lymphoma, leukemia, and metastasis to the pituitary. In our patient, the left eye oculomotor nerve palsy suggested two main differential diagnoses as diabetic cranial neuropathy or cavernous sinuses involvement.

A comprehensive review on the management of III nerve palsy suggested that when a patient presents with an acute onset of unilateral limitation of an eye, the defect should be categorized to “complete or partial” and “with or without the involvement of the pupil” to come to a diagnosis. Pupil-sparing in old patients with known systemic vascular disease can suggest ischemic mononeuropathy as a common cause [14]

The adjacent cavernous sinus infiltration involving nerve III, IV, and VI, usually induces cranial nerve palsy in decreasing order of frequency. 6th nerve palsy is relatively uncommon because it is well sheltered in the cavernous sinus [7]. In diabetic neuropathy, multiple cranial nerve palsies are extremely rare, and pupillary reflex usually spared because the ischemic lesion is confined to the core of the nerve and does not affect peripherally situated pupillomotor fibers [15]. Although diabetic neuropathy is the most common cause of third nerve palsy, it is advisable to perform a brain MRI to exclude other causes of oculomotor nerve palsy [16].

On the other hand, poor glycemic control or rapid treatment of hyperglycemia could increase the risk of diabetic neuropathy [17]. It may have an acute onset resulting from ischemic infarction of the vasa nervorum [18]. Diabetic neuropathy was less suggested in our patient due to well-controlled diabetes, the chronic and insidious presentation of the symptoms, and multi-neuropathy involvement.

Sato et al. stated that isolated oculomotor nerve palsy was most frequently associated with the large B-cell lymphoma cell type. Pupil sparing oculomotor nerve palsy suggests infarction of the oculomotor nerve, as is commonly observed in patients with diabetes mellitus; despite this, there was no infarction of the oculomotor nerve on histological examination in the reported cases with lymphoma and isolated oculomotor palsy [19] These findings suggest that whether the pupil is involved or spared may depend on damage to the pupilomotor fibers in the oculomotor nerve by infiltration or compression by lymphoma. Moreover, as acknowledged by Brazis, compressive cavernous sinus lesions might spare the pupil “because they often involve only the superior division of the oculomotor nerve that carries no pupillomotor fibers, or the superior aspect of the nerve anterior to the point where the pupillomotor fibers descend in their course near the inferior oblique muscle” [15]

Excluding neoplastic disorders, other etiologies of multiple cranial nerve palsy include infections (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis), inflammatory diseases (e.g., sarcoidosis, vasculitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, amyloidosis, connective tissue disease, rheumatoid arthritis), vascular disease (e.g., diabetes, aneurysm, carotid artery dissection, sickle-cell disease), bone disease (e.g., Paget’s disease) and trauma (e.g., closed head injury) [20].

Regarding the source of the lymphoma, pituitary lymphoma is very rare, and there is no report for extra-sellar spreading in literature till now [21]. On the other hand, malignancy of WR lymphoid tissue and primary involvement of nasopharyngeal is an uncommon tumor that includes a small part of NHL and has the potential to infiltrate the adjacent tissues [1]. So, in this case nasopharyngeal lymphoma was more probable than primary CNS lymphoma.

A few studies are reporting the clinical characteristics of NH lymphomas [22, 23]. Hsueh et al. reported that in 35 cases of NPL during 22 years’ follow-up with the average age of 59.6 years, WBC of 12,992/mm3, LDH of 337.7 U/L, and the meantime from initial symptoms to diagnosis of 2.6 months, neck lymph nodes involvement or other distant involvements were detected in less than a third of patients at the time of diagnosis. Also, 14.3% of the patients were presented with B symptoms. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma was the most common pathological diagnosis of nasopharyngeal (n = 17), followed by NK/T cell lymphoma (n = 9). Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, mantle cell lymphoma, and small lymphocytic lymphoma was the other pathologic diagnoses [5]. To compare our patient with Hsueh et al. study, our patient had leukopenia and a longer duration from initial symptoms (i.e., diplopia) to diagnosis (about 9 months) and similar age and LDH levels. Pathological findings in our patient were compatible with mantle zone lymphoma, which was one of the lesser-known cases in NH lymphomas. Our patient’s presentations were noteworthy due to her pituitary and cavernous sinus involvement, while she had no remarkable B-symptoms and nasal involvement. Unusual manifestations of a rare disease led to a prolonged diagnosis.

NHL of the nasopharyngeal region is usually invasive and has a strikingly poor prognosis than other extranodal lymphomas [24]. Also, localized disease and low-grade NPL are associated with a better prognosis [22]. Moreover, B symptoms have been reported to be associated with poor prognosis [25]. Our patient suggested having a relatively good prognosis due to her localized and low-grade disease.

There are limited data regarding epidemiologic and treatment outcomes of NH lymphoma [5]. The treatment of localized disease (stage I, II and non-bulky disease) with activity index less than 2 and normal LDH level is based on the CHOP regimen (3 to 4 cycles) plus Rituximab (if CD20 positive in immunochemistry). Based on Allam et al. study, More than 80% of patients may be successfully treated by this regimen [22]. Our patient responded to chemotherapy and resolved her hematological defects.

Glucocorticoids act as a down-regulatory signal to suppress arginine vasopressin (AVP (and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH (secretion via negative feedback loops, respectively. In patients with hypocortisolism, glucocorticoid deficiency stimulates CRH, and therefore AVP release. So glucocorticoid replacement could increase free water excretion and unmask the concomitant CDI [26] as showen in our patient. Although pituitary dysfunction was improved in most cases, complete recovery occurred less frequently [27]. Adrenal insufficiency, central hypothyroidism and CDI have been resolved in our patient.

To our best knowledge, we found 17 cases of NPL with cranial nerve palsy, 1 case of NPL with pan-hypopituitarism and no NPL case with both cranial nerve palsy and pituitary dysfunction as showed in Table 2 [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

In conclusion, we presented for the first time a unique case of NPL with an unusual presentation of oculomotor nerve palsy associated with pan-pituitary involvement in a diabetic patient. The incidence of cranial neuropathy in patients with diabetes should not merely be attributed to diabetic neuropathy without further evaluation.

Availability of data and materials

All data used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NPL:

-

Nasopharyngeal lymphoma

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell

- WBC:

-

White blood cell count

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- PPD:

-

Purified protein derivative

- P-ANCA:

-

Perinuclear anti-neutrophil antibodies

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- C-ANCA:

-

Cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil antibodies

- TSH:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- ACTH:

-

Adrenocorticotrophic, hormone

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone

- FSH:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- IGF-1:

-

Insulin growth factor-1

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- IHC:

-

Cell immunohistochemistry

- HRCT:

-

High-resolution computed tomography

- CHOP:

-

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone

- CDI:

-

Central diabetes insidious

- AVP:

-

Arginine vasopressin

- CRH:

-

Corticotropin-releasing hormone

References

Wu R-Y, Li Y-X, Wang W-H, Jin J, Wang S-L, Liu Y-P, Song Y-W, Fang H, Ren H, Liu Q-F. Clinical disparity and favorable prognoses for patients with Waldeyer ring extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37(1):41–6.

Smith A, Crouch S, Lax S, Li J, Painter D, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Lymphoma incidence, survival and prevalence 2004–2014: sub-type analyses from the UK’s Haematological malignancy research network. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(9):1575–84.

Sun J, Yang Q, Lu Z, He M, Gao L, Zhu M, Sun L, Wei L, Li M, Liu C. Distribution of lymphoid neoplasms in China: analysis of 4,638 cases according to the World Health Organization classification. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138(3):429–34.

Rosenberg SA, Diamond HD, Jaslowitz B, Craver LF. Lymphosarcoma: a review of 1269 cases. Medicine. 1961;40(1):31–84.

Hsueh C-Y, Yang C-F, Gau J-P, Kuan EC, Ho C-Y, Chiou T-J, Hsiao L-T, Lin T-A, Lan M-Y. Nasopharyngeal lymphoma: a 22-year review of 35 cases. J Clin Med. 2019;8(10):1604.

Freda PU, Beckers AM, Katznelson L, Molitch ME, Montori VM, Post KD, Vance ML. Pituitary incidentaloma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(4):894–904.

Komninos J, Vlassopoulou V, Protopapa D, Korfias S, Kontogeorgos G, Sakas DE, Thalassinos NC. Tumors metastatic to the pituitary gland: case report and literature review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(2):574–80.

Bonneville JF, Bonneville F, Cattin F. [MRI of the pituitary gland: indications and results in gynaecology and in obstetrics].Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2005;33(3):147–53.

Ng S, Fomekong F, Delabar V, Jacquesson T, Enachescu C, Raverot G, Manet R, Jouanneau E. Current status and treatment modalities in metastases to the pituitary: a systematic review. J Neuro-Oncol. 2020;146(2):219–27.

Shimon I. Metastatic Spread to the Pituitary. Neuroendocrinology. 2020;110(9-10):805–8.

He W, Chen F, Dalm B, Kirby PA, Greenlee JD. Metastatic involvement of the pituitary gland: a systematic review with pooled individual patient data analysis. Pituitary. 2015;18(1):159–68.

Novák V, Hrabálek L, Hampl M, Hoza J, Fryšák Z, Vaverka M. Metastatic pituitary disorders. Klin Onkol. 2017;30(4):273–81.

Carpinteri R, Patelli I, Casanueva F, Giustina A. Inflammatory and granulomatous expansive lesions of the pituitary. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23(5):639–50.

Ganger A. A comprehensive review on the management of III nerve palsy. Delhi J Ophthalmol. 2016;27(2):86–91.

Brazis PW. Isolated palsies of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. In: Seminars in neurology: 2009: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2009. p. 014–28.

Said G. Diabetic neuropathy--a review. Nat Clin Pract Neuroly. 2007;3(6):331–40.

Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Treatment-induced diabetic neuropathy: a reversible painful autonomic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(4):534–41.

Bansal V, Kalita J, Misra U. Diabetic neuropathy. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(964):95–100.

Sato H, Hashimoto T, Yoneda S, Hirabayashi K, Oguchi K, Higuchi K. Lymphoma as a cause of isolated oculomotor nerve palsy. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18(9):1256–8.

Carroll CG, Campbell WW: Multiple cranial neuropathies. In: Seminars in neurology: 2009: © Thieme Medical Publishers; 2009. p.53–65.

Tarabay A, Cossu G, Berhouma M, Levivier M, Daniel RT, Messerer M. Primary pituitary lymphoma: an update of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2016;130(3):383–95.

Allam W, Ismaili N, Elmajjaoui S, Elgueddari BK, Ismaili M, Errihani H. Primary Nasopharyngeal non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a retrospective review of 26 Moroccan patients. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2009;9(1):11.

Lei K-K, Suen J, Hui P, Tong M, Li W, Yau S. Primary nasal and nasopharyngeal lymphomas: a comparative study of clinical presentation and treatment outcome. Clin Oncol. 1999;11(6):379–87.

Yuan Z, Li Y, Zhao L, Gao Y, Liu X, Gu D, Qian T, Yu Z. Clinical features, treatment and prognosis of 136 patients with primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the nasopharynx. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2004;26(7):425–9.

Urquhart A, Berg R. Hodgkin's and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(9):1565–9.

Chin H, Quek T, Leow M. Central diabetes insipidus unmasked by corticosteroid therapy for cerebral metastases: beware the case with pituitary involvement and hypopituitarism. JR Coll Phys Edinb. 2017;47:247–9.

Foo SH, Sobah SA: Burkitt’s lymphoma presenting with hypopituitarism: a case report and review of literature. Endocrinol Diab Metab Case Rep 2014, 2014(1).

Mohammadianpanah M, Ahmadloo N, Mozaffari MA, Mosleh-Shirazi MA, Omidvari S, Mosalaei A. Primary localized stages I and II non- Hodgkin's lymphoma of the nasopharynx: a retrospective 17-year single institutional experience. Ann Hematol. 2009;88(5):441–7.

Da Silva RL, Fernandes T, Lopes A, Santos S, Mafra M, Rodrigues AS, de Sousa AB. B lymphoblastic lymphoma presenting as a tumor of the nasopharynx in an adult patient. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4(4):318–23.

Kay MC, McCrary JA. Multiple cranial nerve palsies in late metastasis of midline malignant reticulosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88(6):1087–90.

Keane JR. Twelfth-nerve palsy: analysis of 100 cases. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(6):561–6.

Riggs HE, Rupp C, Ray H, Yaskin JC. Cranial nerve syndromes associated with nasopharyngeal malignancy. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatr. 1957;77(5):473–82.

Van der Vliet H, van Oers M, Schot L, Majoie C, van der Meer J. A space-occupying lesion of the skull base, masked by nasopharyngeal lymphatic tissue hypertrophy and causing cranial nerve dysfunction in an HIV-infected patient. Ann Hematol. 2002;81(3):164–6.

Ingram L, Fairclough D, Furman W, Sandlund J, Kun L, Rivera G, Pui CH. Cranial nerve palsy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer. 1991;67(9):2262–8.

Bunick EM, Hirsh LF, Rose LI. Panhypopituitarism resulting from Hodgkin’s disease of the nasopharynx. Cancer. 1978;41(3):1134–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FH, MZ and RHA: wrote the manuscript, SH: contributed in the patient discussion and final diagnosis, MT: performed immunohistochemical staining of the lesion, MM: referred the case from the private clinic and edited the manuscript, FH: reviewed and edited manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Series Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zahedi, M., Hizomi Arani, R., Tohidi, M. et al. Nasopharyngeal B-cell lymphoma with pan-hypopituitarism and oculomotor nerve palsy: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Endocr Disord 20, 163 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00644-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-020-00644-y