Abstract

Background

Persistent diabetes-related distress (DRD) is experienced by patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Knowing factors associated with persistent DRD will aid clinicians in prioritising interventions efforts.

Methods

A total of 216 patients were recruited from a tertiary hospital in Singapore, an Asian city state, and followed for 1.5 years (2011–2014). Data was collected by self-completed questionnaires assessing DRD (measured by the Problem Areas in Diabetes score) and other psychosocial aspects such as social support, presenteeism, depression, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) at three time points. Clinical data (body-mass-index and glycated haemoglobin) was obtained from medical records. Change score was calculated for each clinical and psychosocial variable to capture changes in these variables from baseline. Generalized Linear Model with Generalized Estimating Equation method was used to assess whether baseline and change scores in clinical and psychosocial are associated with DRD over time.

Results

Complete data was available for 73 patients, with mean age 44 (SD 12.5) years and 67% males. Persistent DRD was experienced by 21% of the patients. In the final model, baseline HRQoL (OR = 0.56, p < 0.05) and change score of EDS (OR = 1.22, p < 0.05) was significantly associated with DRD over time.

Conclusions

EDS might be a surrogate marker for persistent DRD and should be explored in larger samples of population to confirm the findings from this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Persistent diabetes-related distress (DRD), which is defined as distress experienced over at least nine months [1] has been shown to lead to clinical depression [2]. Lipscombe et al. found that baseline factors such as being older, not married, having more complications and chronic conditions, having less family support and being depressed were associated with increasing and severe levels of distress [3].

The aim of this study is to explore changes in clinical (such as body mass index (BMI) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c)) and psychosocial factors (such as social support, presenteeism, depression, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS)), above and beyond baseline, and their association with DRD over time. Observed significant changes will enable researchers and clinicians to prioritise their interventions [4] to prevent the development of persistent DRD.

Methods

This is a longitudinal study on psychological outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus with data collected over three time-points (baseline “B”, first follow-up “F1” at 6 months and second follow-up “F2” between 12 and 18 months) conducted at a single tertiary hospital in Singapore [5]. Only patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) were included in this analysis. The institutional review board of the National Healthcare Group reviewed and approved the study protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Socio-demographic information were collected using self-administered questionnaires, clinical factors, such as BMI, HbA1c and medication usage were retrieved from electronic medical records (EMR) and medical history of co-morbidities (i.e., cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, nephropathy, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease and anaemia) were captured through a combination of self-report and EMR.

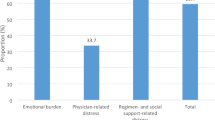

Distress was measured with the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID), with scores 40 and above indicative of severe DRD [6]. Social support was measured with two items: 1) single item measuring support from family using the Family Functioning Measure [7]; 2) Question 22 from the World Health Organisation Quality of Life Brief questionnaire measuring support from friends [8]. Presenteeism was measured using the modified question “On a scale of 0 “Least effective” to 10 “Most effective”, how effective are you at work?” [9]. Depression was captured using Kessler-10 Psychological Distress Scale [10]. HRQoL was measured with the Audit of Diabetes-Dependent Quality of Life [11]. EDS was measured using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale [12].

Statistical analysis

Generalized linear model (GLM) with the Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) method was used to model the longitudinal binary outcome. Three steps were taken to generate the final model: Step 1, we performed a regression analysis for each selected clinical and psychosocial variables at baseline with adjustment for time (i.e., baseline, follow-up 1 and 2) (M1). Step 2, on top of the baseline clinical or psychosocial variable from M1, we added its corresponding change score which captures its change from baseline (M2). In step 3, in addition to the variables in M2, we adjusted for baseline socio-demographic (Age, Gender: Male/Female, Ethnicity: Chinese/Non-Chinese), medication usage (Insulin: Yes/No) and comorbidities (Yes/No) (M3). Our final model included clinical and psychosocial variables which were significant in M3 and baseline socio-demographic, medication usage and comorbidities. As the change scores were considered higher order terms to the baseline variables, the baseline would be included into the final model although only the change score was significant.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 for Windows (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

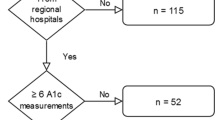

Of the 216 subjects recruited at baseline, only 73 patients had complete data at three time-points from 2011 to 2014, resulting in an overall attrition rate of 66.2%. A comparison of subjects at baseline and those who did not return can be found in Table 1. The patients who did not return were not different from those at baseline in their clinical and psychosocial characteristics.

Table 2 presented the results of the various models with varying degree of adjustment and the results were in general consistent in the direction of association among the significant findings. In the first model with adjustment for time only (M1), baseline HbA1c, support from friends, depression and HRQoL were significantly associated with DRD over time. When change scores were included into the models (M2), only baseline depression and baseline HRQoL remained significantly associated with current distress. Although baseline EDS remained insignificant in both M1 and M2, change in current EDS (from baseline) was significantly associated with DRD over time. The significant findings in M2 persisted after adjusting for baseline socio-demographic, medication use and comorbidities (M3). Interestingly, baseline HbA1c became significantly associated with DRD over time in M3 even though it was not significant in M2 but significant in M1.

The final model (Table 3) included all significant clinical and psychological variables from M3. Baseline HRQoL and change score of EDS remained significantly associated with DRD over time, where higher HRQoL at baseline significantly reduced the odds of DRD (OR = 0.60, p < 0.01) over time but increase in EDS from baseline over time was significantly associated with increased odds in DRD over time (OR = 1.22, p < 0.01).

Discussion

In this study, we found that increase in current EDS from baseline, was significantly associated with increased odds of DRD over time, suggesting the compound negative impact of EDS on DRD with time. Possible explanations for this include: 1) EDS has been shown to be associated with reduced motivation to engage in diabetes self-management activities [13], which ultimately results in poorer control [14] and hence DRD [15]; 2) EDS being positively associated with depression [16], which has also shown to be associated with DRD [17]; and 3) EDS is associated with sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), restless leg syndrome (RLS) and insomnia [18] which have been shown to negatively affect HbA1c [14], further aggravating the DRD. This suggests that EDS can be used as a surrogate marker for DRD and can be addressed in interventions that aims to reduce DRD.

Of particular interest was the finding that persistent DRD was only associated with psychosocial rather than clinical variables in our study. These findings corroborated with previous studies which showed that psychosocial variables had a larger impact on DRD over time compared to clinical factors [19, 20]. One postulation is that clinical variables are indicators of the emotional stresses experienced by patients [20], since patients with diabetes may suffer from distress due to the disease and the challenges from the daily grind of living, managing and caring for diabetes [21]. Another possibility is related to the concept whereby patients’ behaviours are primarily driven by their own perceptions and their surrounding influences [22]. Given that T2DM is a chronic condition which involves a life-long process of complex and demanding set of self-management instructions, DRD is likely to be driven by patients’ perceptions rather than the disease status of the patients. This would suggest the importance of behavioural intervention to help patients cope with DRD.

Based on a literature review on PUBMED, no studies were found to have addressed the association between EDS and DRD. However, studies have shown the association between EDS and depression [16, 23]. In fact, Koutsourelakis et al noted that depression and diabetes were key determinants of EDS among those with OSA [24]. As such, it is possible that the relationship between EDS and DRD is bidirectional. To factor in the possibility of reversal causality in our findings, we reanalysed Model 3 with DRD as a continuous variable and modelled both baseline and change in EDS as endogenous variables that were functions of DRD. The results from the reanalysis were similar to Table 3, suggesting the robustness of the significant association between changes in EDS and DRD, and clinicians should consider addressing EDS in routine clinic sessions.

While this study presents novel findings, a major limitation faced was the large attrition of patients from the cohort. This not only severely limited the power of the analysis, but could have introduced bias in the findings. However, when we compared the clinical and psychosocial characteristics between those who returned for the follow-ups and those who did not, there were no significant differences between the two groups (Table 1) suggesting bias in the findings might be minimal.

Second, we did not collect additional information on sleep phenotype, apart from the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. In patients with T2DM, EDS has been shown to be associated with sleep disorders such as OSA, RLS and insomnia [18, 25, 26]. However, the study by Dixon et al has shown that EDS was more associated with poor energy, depression and symptoms of nocturnal sleep disturbance than OSA in obese patients [27]. Nonetheless, future work addressing the issue of sleep in patients with T2DM should include other measures of sleep to have a better understanding on how sleep affects the emotional aspects of patients with T2DM.

Last, our sample was drawn from a specialist outpatient clinic of the National University Hospital thus limiting the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusion

Increased EDS, above and beyond baseline, and baseline HRQoL were associated with persistent DRD. Given that the change in EDS appears to have an impact on persistent DRD in our study, clinicians could consider looking out for signs of EDS during routine clinical practice to address persistent DRD. However, in light of the limited sample size of this study, it is important for larger cohorts to study the effect of EDS on DRD to confirm the findings.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DRD:

-

Diabetes-related distress

- EDS:

-

Excessive daytime sleepiness

- EMR:

-

Electronic medical records

- GEE:

-

Generalized estimating equation

- GLM:

-

Generalized linear model

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated haemoglobin

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- PAID:

-

Problem areas in diabetes

- PUBMED:

-

Search engine accessing primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics

- RLS:

-

Restless leg syndrome

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

References

Fisher L, Skaff M, Mullan J, Arean P, Glasgow R, Masharani U. A longitudinal study of affective and anxiety disorders, depressive affect and diabetes distress in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25(9):1096–101.

Ehrmann D, Kulzer B, Haak T, Hermanns N. Longitudinal relationship of diabetes-related distress and depressive symptoms: analysing incidence and persistence. Diabet Med. 2015;32(10):1264–71. Epub 2015/07/24.

Lipscombe C, Burns RJ, Schmitz N. Exploring trajectories of diabetes distress in adults with type 2 diabetes; a latent class growth modeling approach. J Affect Disord. 2015;188:160–6. Epub 2015/09/13.

Young-Hyman D, de Groot M, Hill-Briggs F, Gonzalez JS, Hood K, Peyrot M. Psychosocial Care for People With Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(12):2126–40. Epub 2016/11/24.

Tan LS, Khoo EY, Tan CS, Griva K, Mohamed A, New M, et al. Sensitivity of three widely used questionnaires for measuring psychological distress among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(1):153–62. Epub 2014/06/29.

Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Krichbaum M, Kubiak T, Haak T. How to screen for depression and emotional problems in patients with diabetes: comparison of screening characteristics of depression questionnaires, measurement of diabetes-specific emotional problems and standard clinical assessment. Diabetologia. 2006;49(3):469–77. Epub 2006/01/25.

Stewart AL, Ware JE. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach: Duke University Press; 1992.

WHOQOL Group. WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment, Programme on Mental Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. PharmacoEconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65. Epub 1993/10/05.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-L, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(06):959–76.

Bradley C. The development of an individualized questionnaire measure of perceived impact of diabetes on quality of life: the ADDQoL. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:79–91.

Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–5.

Chasens ER, Olshansky E. Daytime sleepiness, diabetes, and psychological well-being. Issues in mental health nursing. 2008;29(10):1134–50. Epub 2008/10/15.

Keskin A, Unalacak M, Bilge U, Yildiz P, Guler S, Selcuk EB, et al. Effects of Sleep Disorders on Hemoglobin A1c Levels in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Chin Med J. 2015;128(24):3292–7. Epub 2015/12/17.

Co MA, Tan LS, Tai ES, Griva K, Amir M, Chong KJ, et al. Factors associated with psychological distress, behavioral impact and health-related quality of life among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(3):378–83. Epub 2015/02/11.

Pamidi S, Knutson KL, Ghods F, Mokhlesi B. Depressive symptoms and obesity as predictors of sleepiness and quality of life in patients with REM-related obstructive sleep apnea: cross-sectional analysis of a large clinical population. Sleep Med. 2011;12(9):827–31. Epub 2011/10/08.

Burns RJ, Deschenes SS, Schmitz N. Cyclical relationship between depressive symptoms and diabetes distress in people with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from the Montreal Evaluation of Diabetes Treatment Cohort Study. Diabet Med. 2015;32(10):1272–8. Epub 2015/07/24.

Resnick HE, Redline S, Shahar E, Gilpin A, Newman A, Walter R, et al. Diabetes and sleep disturbances: findings from the Sleep Heart Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):702–9. Epub 2003/03/01.

Fisher L, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, Glasgow RE, Arean P, Hessler D. Predicting diabetes distress in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabet Med. 2009;26(6):622–7.

Karlsen B, Oftedal B, Bru E. The relationship between clinical indicators, coping styles, perceived support and diabetes-related distress among adults with type 2 diabetes. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(2):391–401. Epub 2011/06/29.

Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Welch G, Jacobson AM, Aponte JE, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(6):754–60. Epub 1995/06/01.

Fife BL. The conceptualization of meaning in illness. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(2):309–16. Epub 1994/01/01.

Medeiros C, Bruin V, Ferrer D, Paiva T, Montenegro Junior R, Forti A, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in type 2 diabetes. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2013;57(6):425–30. Epub 2013/09/14.

Koutsourelakis I, Perraki E, Bonakis A, Vagiakis E, Roussos C, Zakynthinos S. Determinants of subjective sleepiness in suspected obstructive sleep apnoea. J Sleep Res. 2008;17(4):437–43. Epub 2008/09/03.

Eriksson AK, Ekbom A, Granath F, Hilding A, Efendic S, Ostenson CG. Psychological distress and risk of pre-diabetes and Type 2 diabetes in a prospective study of Swedish middle-aged men and women. Diabet Med. 2008;25(7):834–42. Epub 2008/06/03.

Lopes LA, Lins Cde M, Adeodato VG, Quental DP, de Bruin PF, Montenegro Jr RM, et al. Restless legs syndrome and quality of sleep in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2633–6. Epub 2005/10/27.

Dixon JB, Dixon ME, Anderson ML, Schachter L, O'Brien PE. Daytime sleepiness in the obese: not as simple as obstructive sleep apnea. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(10):2504–11. Epub 2007/10/11.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education Singapore Academic Research Fund Tier 1 (Grant No.: FY2011-FRC3-007).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

MLT performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CST provided the expertise on statistical analysis. EYHK, HLW, KG and YSL wrote the protocol and designed the study. JL and EST provided expert opinion on the design of the study, the analyses of the paper and the interpretation of the results and discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) of the National Healthcare Group (NHG) reviewed and approved the study protocol. The NHG DSRB represents the Republic of Singapore. Informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, M.L., Tan, C.S., Griva, K. et al. Factors associated with diabetes-related distress over time among patients with T2DM in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. BMC Endocr Disord 17, 36 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-017-0184-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-017-0184-4