Abstract

Background

Duodenal Diaphragm in adults is very uncommon, caused by congenital and acquired changes. It is reported that acquired duodenal diaphragm is related to the long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Case summary

We report an adult presentation of duodenal diaphragm in a 77-year-old woman, suffered from acute cholangitis and choledocholithiasis. She was performed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedure to remove the stone in common bile duct (CBD). After the stenosis ring dilated by endoscopic balloon dilatation, ERCP procedure was applied, and the CBD stone was removed successfully.

Conclusion

Duodenal diaphragm is difficult to diagnose in clinic. Although the patient in this case had relatively mild symptoms of incomplete upper hemi-abdominal obstruction, these symptoms could be obscured by the emergency acute upper abdominal pain with fever as clinical manifestations of acute cholangitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Duodenal diaphragm usually presents in infancy or childhood with congenital etiology, and it is rare in adults. We report an adult presentation of duodenal diaphragm in a 77-year-old Chinese woman, who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedure to remove the stone in common bile duct (CBD). The occurrence of adult duodenal diaphragm in current case may associate with long-term application of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Case presentation

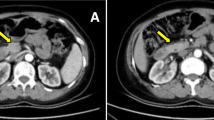

The patient in our case came to Huaibei People’s Hospital emergently accompanied with a 10-h history of acute upper abdominal pain and persistent fever. In order to receive ECRP treatment, she was transferred from local hospital with the diagnosis of acute cholangitis and choledocholithiasis. She had the history of rheumatoid arthritis for 30 years, with irregular treatment by traditional Chinese medicine, NSAIDs and steroids (ibuprofen, indometacin, and prednisone). She also had a history of progressive epigastric fullness for half a year, accompanied with bloating, nausea and occasional emesis after meals, with her body weight decreased for 7.5 kg. Recently, she had three episodes of acute abdominal pain, chills and fever. She have received norfloxacin orally at local clinic, without looking for professional help. Physical examinations revealed a febrile (body temperature 37.6 ℃), and extremely emaciated old woman weighed 34 kg (body mass index 14.5) without jaundice. Abdomen was soft with no tenderness or palpable mass. Her serum albumin level was 22 g/L, and she was anemic with hemoglobin 36 g/L; her white blood cell count was 15.9 × 109/L and serum amylase level was normal. Emergency abdominal CT scan represented that there was a stone in lower part of CBD and a muddy stone in gallbladder (Fig. 1a). According to this critical and emergency situation, she received fluid resuscitation, antibiotic injection and 4-unit red blood cell transfusion.

Imaging data for the patient. a Abdominal computed tomography showed a high density stone in CBD; b endoscopic view of gastric ulcer in pylorus; endoscopic appearance of a duodenal diaphragm with a 2 mm aperture, close view (c) and endoscopic dilatation view (d); e endoscopic view of balloon catheter in situ; f radiographic image of balloon dilatation. g After dilatation of diaphragm in the lumen, endoscopic tube passed through the stricture, ERCP radiography presented a 1 mm stone in CBD; h stone was pulled out through basket

The next day of admission, the patient signed the consent form of ERCP and gastroscopy procedure, which did not contain the item of biopsy. Then the ERCP procedure was performed on her after her vital signs were stable. Unfortunately, this patient needed for the urgent intervention at that time, thus we did not have enough time to perform the differential diagnostic procedures. Gastroscopy showed an irregular ulceration in the anterior pyloric area (Fig. 1b), and a diaphragm with a 2 mm aperture in the descending part of duodenum (Fig. 1c). The gastroscopic tube cannot pass the aperture. The patient was suffering from critical acute cholangitis, and the failure of ERCP treatment may progress to acute severe cholangitis and sepsis.

We inserted a yellow wire via the stenotic hole to explore whether it was a fistular passway to adjacent organs or the gut (Fig. 1d). By using the X-ray, we found that it connected to the remaining duodenum. The stenotic part of duodenum was short and the diaphragm was soft, so we tried to make the gastroscopic tube pass through the stenotic hole to ensure the successful removal of the CBD stone by balloon catheter dilation. We inserted 10 mm, 12 mm and 14 mm balloon dilatations through stenosis ring respectively (Fig. 1e, f), mild bleeding occurred after the procedure without other complications. Then the gastroscopic tube passed through the stenotic part of duodenum, we switched to the duodenal endoscopy to continue the ERCP procedure. After the balloon dilatation of the papilla, the CBD stone was removed successfully (Fig. 1g, h). After 8 days of hospital stay and medication therapy, her condition was relieved with lab results of hemoglobin 90 g/L and white blood cell count 6.4 × 109/L.

We concluded the final diagnosis as follows: acute cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, gastric ulcer, iron-deficiency anemia, duodenal diaphragm, hypoproteinemia, rheumatoid arthritis and severe malnutrition. Her gastric ulcer, severe anemia and malnutrition might be caused by long term NSAIDs ingestion and food retention due to the upper hemi-abdominal obstruction. Duodenal diaphragm may result from long term NSAIDs usage. We attempted to contact her for a 3-month follow-up after her discharge, but we received no response till now.

Discussion and conclusion

The presence of duodenal membrane, which is an entity usually identified in infant or children with congenital etiology, is clinically characterized by postprandial vomits of acid and bilious food contents, accompanied by upper hemi-abdominal distention with visible peristalsis and borborygmus. Developmental delay is an important parameter, associated to several conditions such as Down syndrome, prematurity, situs inversus and coexisting extrinsic abnormalities [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

It is reported that acquired duodenal diaphragm is related to long-term use of NSAIDs [9]. Initially it was unknown whether this patient with duodenal diaphragm had congenital etiology or acquired pathogenesis. According to her history consultation, she had a 30-year history of irregular NSAIDs treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Her symptoms implied the clue for upper hemi-abdominal obstruction, including progressive epigastric fullness, bloating, nausea, and occasional emesis after meals for half a year No similar symptoms were explored before then, therefore, we concluded the diagnosis of acquired duodenal diaphragm.

NSAIDs could contribute to diaphragm-like strictures and ulceration in the small bowel and colon, which typically presents as anemia and bowel obstruction. Diaphragm disease was firstly described by Lang et al. [10]. He reported seven patients with NSAIDs treatment, had developed small bowel strictures resembling perforated diaphragms. The first case of colonic strictures with ulceration was demonstrated by Sheers and Williams [11].

While the symptoms and adverse events are well documented, the detailed pathogenesis of bowel diaphragms remains elusive at present. Going et al. [12] suggested that circumferential ulceration in gut might be the precursor of intestinal diaphragms. The small intestinal diaphragms caused by long-term use of NSAIDs and duodenal diaphragms are similar macroscopically and microscopically [13]. In both cases, diaphragms were formed by the mucosa and submucosa of affected bowels without evidence of scarring or thickening on the serosal surface. Therefore, some researchers [13, 14] speculated that the acquired pathogenesis is related to NSAIDs ingestion. In 1971, Bilbao et al. [15] described a large series of 12 ring-like strictures in the descending duodenum with postbulbar duodenal ulcers. Although some hypotheses of acquired pathogenesis in duodenal diaphragms have been made, it is still unclear whether NSAIDs were an etiologic factor or not.

Several possible etiologies of duodenal strictures should be differentiated, including potassium-induced stricture or neoplastic, ischemic, inflammatory (e.g., Crohn’s disease), and infectious (e.g., tuberculosis) causes, all of which could be excluded by clinical and pathologic grounds.

Many open or laparoscopic procedures have been applied in the surgical treatment of duodenal diaphragm, however, longitudinal duodenotomy with excision of the diaphragm and transverse closure of the duodenotomy is the most prevalent approach for congenital duodenal diaphragm (CDD) treatment [4, 5]. With the advent of endoscopic procedures, the endoscope has become an increasingly powerful therapeutic tool to all types of gastrointestinal strictures. Treatment with different procedures such as endoscopic membranotomy with laser [16], sphincterotome [17], high-frequency-wave snare/cutter [17], hot biopsy forceps [18], insulated-tip diathermic knife [19] and needle knife [20] has been reported. Endoscopic therapy has become popular for a number of reasons: no abdominal incision (scar), no complications such as adhesion development, shorter hospital stays, and sometimes no need of general anesthesia. More invasive endoscopic procedures have been reported, such as cutting the web with an electrocautery device or laser carry risks of perforation, causing excessive bleeding and trauma to the ampulla of Vater. Contrarily, endoscopic dilatation is a relatively safe way with a low risk of mentioned complications, just as we did for the patient in our case.

Altogether, NSAIDs may cause numerous side effects, most seen in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. NSAID-induced gastrointestinal ulcer is the main complication. Acquired duodenal diaphragm is a very rare malformation, it should be suspected in the cases of abdominal distension and malnutrition. Endoscopy could be used to identify the diagnosis. Endoscopic balloon dilation is a simple and effective method to treat this condition.

Abbreviations

- ERCP:

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- CBD:

-

Common bile duct

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

References

Dallas SL, Prideaux M, Bonewald LF. The osteocyte: an endocrine cell … and more. Endocr Rev. 2013;34(5):658–90.

Ozturk H, et al. A comprehensive analysis of 51 neonates with congenital intestinal atresia. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(7):1050–4.

Ein SH, Palder SB, Filler RM. Babies with esophageal and duodenal atresia: a 30-year review of a multifaceted problem. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(3):530–2.

Mustafawi AR, Hassan ME. Congenital duodenal obstruction in children: a decade’s experience. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008;18(2):93–7.

Bailey PV, et al. Congenital duodenal obstruction: a 32-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28(1):92–5.

Brown C, et al. Situs inversus abdominalis and duodenal atresia: a case report and review of the literature. S Afr J Surg. 2009;47(4):127–30.

Stringer MD, et al. Double duodenal atresia/stenosis: a report of four cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27(5):576–80.

Arena F, et al. An uncommon case of associate intrinsic and extrinsic stenosis of the duodenum in newborn. Pediatr Med Chir. 2008;30(4):212–4.

Rha SE, et al. Duodenal diaphragm associated with long-term use of nonsteriodal antiinflammatory drugs: a rare cause of duodenal obstruction in an adult. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(3):920–1.

Lang J, et al. Diaphragm disease: pathology of disease of the small intestine induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41(5):516–26.

Sheers R, Williams WR. NSAIDs and gut damage. Lancet. 1989;2(8672):1154.

Watts GT. Possible precursor of diaphragm disease in the small intestine. Lancet. 1993;341(8850):961.

Kannan S, McGreevy PS, Fullerton TE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced duodenal web. S D J Med. 1997;50(11):393–4.

Blinder GH, et al. Duodenal diaphragmlike stricture induced by acetylsalicylic acid. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39(6):1365–9.

Bilbao MK, et al. Postbulbar duodenal ulcer and ring-stricture. Cause and effect. Radiology. 1971;100(1):27–35.

Bachman BA, Brady PG. Localized gastric varices: mimicry leading to endoscopic misinterpretation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30(4):244–7.

Schuler H, Matuschewski K. Plasmodium motility: actin not actin’ like actin. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22(4):146–7.

Beeks A, et al. Endoscopic dilation and partial resection of a duodenal web in an infant. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(3):378–81.

Barabino A, et al. Successful endoscopic treatment of a double duodenal web in an infant. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(2):401–3.

DiMaio CJ, et al. Pediatric therapeutic endoscopy: endoscopic management of a congenital duodenal web. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(1):166–7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the reviewers for their helpful comments on this paper.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ, SW and YH finished the data analysis, LW, GJ finished the manuscript writing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The patient in our case has signed the informed consent. This study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Huaibei People’s Hospital Anhui Province.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, L., Jia, G., Hu, Y. et al. A rare case of duodenal diaphragm in an adult during ERCP treatment for choledocholithiasis. BMC Surg 20, 273 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00934-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00934-1