Abstract

Background

Kimura’s disease is a rare, benign chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that mostly affects Asians. The disease typically presents as subcutaneous masses in the head or neck region that are predominantly found in the preauricular and submandibular areas.

Case presentation

A 7-year-old boy presenting with paralysis of both lower extremities and a thoracic spine dumbbell mass was initially diagnosed with a neurogenic tumor, but the pathological and laboratory examinations confirmed the diagnosis of Kimura’s disease. The paralysis symptom disappeared rapidly, but the patient had developed a recurrent mass in the cervical vertebral canal at the 9-month follow-up.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, no prior published literature has revealed Kimura’s disease cases that mimic dumbbell neurogenic tumors. Here, we report such a case of Kimura’s disease for the first time and provide a brief review of the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Kimura’s disease is a rare chronic inflammatory disorder that was first reported in China by Kim and Szeto in 1937 [1] and became more widely known after a systematic description was published in 1948 by Kimura et al. [2]. Kimura’s disease mainly affects young Asian (Chinese and Japanese) men between 20 and 40 years of age, although sporadic cases have been described elsewhere [3,4,5]. Clinically, it typically presents as nontender subcutaneous single or multiple nodules in the head and neck regions, which are predominantly found in the preauricular and submandibular area. Masses in the orbit [6, 7], eyelid [8], epiglottis [9], earlobe [10], lacrimal gland [11], parotid gland [12, 13], groin [14], breast [15], and long bones [16] have also been reported. However, to our knowledge, there have been no reports of Kimura’s disease presenting as a posterior mediastinal dumbbell mass extending into the vertebral canal through the intervertebral foramen.

Case presentation

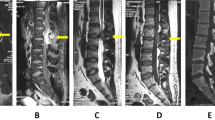

A 7-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital on April 2, 2018, with a complaint of paralysis in both lower extremities lasting for 4 days. Physical examination revealed that he could not move his lower extremities or control urination and defecation. His tendon reflex had disappeared completely in the lower extremities. Some enlarged lymph nodes were found in the neck region. The chest coronal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a dumbbell-shaped mass in the thoracic cavity between T3 and T5 that measured up to 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 1a). Horizontal MRI indicated that the mass extended to the spinal canal and paravertebral region through an enlarged intervertebral foramen. The spinal cord was compressed and obviously displaced (Fig. 1b). The mass was considered an extradural and paravertebral dumbbell-shaped neurilemmoma. On April 3, 2018, the patient underwent surgery for excision of the lesions using a posterior approach. Under general anesthesia, he was intubated with a double-lumen endotracheal tube and was placed in the right semilateral position. Initially, laminectomy was performed from the lower T3 to the upper T5 by making a vertical linear skin incision from T3-T5. An encapsulated yellowish tumor attached to the dura mater was observed through the left intervertebral foramen between T3 and T4. The mass was connected to the root of the third intercostal nerve, which was ligated and sheared. Subsequently, the chest surgeon induced the collapse of the lung and inserted a thoracoscope through the fourth left intercostal space of the clavicular midline. The mass was observed to protrude from the parietal pleura of the third left intercostal space. Therefore, two thoracic portals were added along the fifth intercostal space of the anterior chest wall. Under the thoracoscope, we separated the mass along with the capsule, carefully confirming the sympathetic nerve. As a result, the mass partially crumbled, but we were able to extract it from the pleural cavity. A chest tube was placed direct under vision, the lung was re-expanded, and the other three portals were closed. The duration of the operation was 3 h.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before (a, b) and after treatment (c, d). a the chest coronal MRI showed a dumbbell-shaped mass (arrow) extending to the spinal canal and paravertebrally through an enlarged intervertebral foramen; b sagittal MRI indicated that the mass was located in the spinal canal between T3 and T5 (arrow) and measured up to 5 cm in length. The spinal cord was compressed and displaced; c coronal MRI showed that there was no mass found in the thoracic cavity; d sagittal MRI showed that there was no mass found in the spinal canal between T3 and T5

Histopathological examination of the excised tumor revealed numerous lymphoid follicles with hyperplastic germinal centers. There was massive and prominent infiltration of eosinophils with a few areas that were occupied by eosinophilic microabscesses (Fig. 2), which indicates the eosinophilic hyperplastic lymphogranuloma (Kimura’s disease). The results of laboratory examination were obtained after the operation due to the rapid progression of neurologic deficit and showed that the red blood cell count was 4.09 × 1012/L, hemoglobin was 111 g/L, the white blood cell count was 13.77 × 109/L, platelets were 280 × 109/L and the absolute eosinophil count was 5.78 × 109/L, and there was 42% eosinophilia. Serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) was increased to 572 IU/mL (normal < 250). The other results, including blood urea nitrogen (6.83 mmol/L), serum creatinine level (53.2 μmol/L), and urinalysis, were normal. Immunohistological staining (Fig. 3) was later performed, showing negative staining for CD1a, S-100, and CD34 and positive staining for CD31, Fli and Ki-67. These results confirmed the diagnosis of Kimura’s disease.

Histopathological examination of the excised tumor. a The mass showed prominent infiltration by eosinophils with formation of eosinophilic micro abscesses and hyperplasia of germinal centers (arrow); b there was massive infiltration by eosinophils, predominantly with eosinophilic aggregation in some areas (arrow)

The patient, therefore, was started on 40 mg/day prednisone and responded well after 1 week. The eosinophilia and IgE were stabilized with 5 mg of prednisolone. Two weeks later, the patient could move his lower extremities in the bed. One month later, he could walk with his mother’s help. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient was symptom-free and did not demonstrate any sign of recurrence (Fig. 1c, d). At the 9-month follow-up, the patient had developed a recurrent mass in the cervical vertebral canal with the tapering of medication. However, the patient refused further treatment, and further information is not available.

Discussion and conclusions

We report the case of a 7-year-old boy who complained of paralysis in both lower extremities who had a dumbbell mass in the postmediastinum after MRI examination. The clinical picture initially indicated a neurogenic tumor. Biopsy and histological examination, however, finally identified Kimura’s disease.

Histopathologically, the mass associated with Kimura’s disease is usually characterized by the formation of multiple lymphoid follicles with prominent germinal centers, many of which are infiltrated by eosinophils. Eosinophilic infiltration is massive, with the formation of eosinophilic abscesses [17, 18]. This feature can distinguish Kimura’s disease from angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE), in which lymphoid infiltration is more diffuse and lymphoid follicles and eosinophilic abscesses are only occasionally observed [17, 18]. In addition, in contrast to those in patients with ALHE, peripheral blood eosinophil counts and serum IgE levels are markedly elevated in patients with Kimura’s disease, which was also found in our case. Nephrotic syndrome is also a common presentation, occurring in up to 60% of patients [19]; however, it was not observed in our case. Our patient had normal levels of urea and creatinine and normal urinalysis results. Few studies have focused on the immunohistochemical examination of tissues in patients with Kimura’s disease. Birol et al. showed the positive expression of CD68, CD34, leukocyte common antigen (LCA) and S-100 [20]. Sun et al. reported the presence of LCA, vimentin (VIM), S-100, CD3, CD45RO, CD20, CD79a, CD31, CD34, F8, c-Kit, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-α in Kimura’s disease [21]. However, our results revealed positivity for CD31, Fli and Ki-67 but negativity for CD1a, S-100, and CD34, which were chosen to exclude Langerhans cell granulomatosis [22]. Tumors were considered to originate from Langerhans cells when the neoplastic cells expressed CD1a and S-100 [23].

Therapies for Kimura’s disease include surgical excision, steroids, radiation, and immunosuppressive agents (e.g., cyclosporine). Although they can reduce the size of the lesion and delay disease progression, recurrence is common [24, 25]. In the present case, the patient was treated with a combination of resection of the lesion and oral steroids. Although the patient’s clinical symptoms improved remarkably immediately after the surgery, the patient developed a recurrent mass in the cervical vertebral canal after a 9-month follow-up since the tapering of medication. We planned to prepare for another surgery, radiotherapy, and cyclosporine treatment for the patient, but his parents refused further treatments owing to financial difficulty. Through our search of the PubMed database, we summarized all recurrent Kimura’s cases (Table 1). Notably, there were no neurologic syndrome noted in all the previously published recurrent Kimura’s cases and all the reported reasons for recurrent were tapering of medication.

In conclusion, we reported our experience managing a rare case of Kimura’s disease presenting as a posterior mediastinal dumbbell mass. Although the short-term outcome was good, the patient experienced recurrence at 9 months after surgery. Therefore, additional studies are still warranted to develop an optimal management regimen for rare disease entities.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the conclusions of this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- VIM:

-

Vimentin

- PDGFR:

-

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- LCA:

-

Leukocyte common antigen

- ALHE:

-

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- IgE:

-

Immunoglobulin E

References

Kim H, Szeto C. Eosinophilic hyperplastic lymphogranuloma, comparison with Mikulicz’s disease. Chin Med J. 1937;23(69):700.

Kimura T, Yoshimura S, Ishikawa E. On the unusual granulation combined with hyperplastic changes of lymphatic tissue. Trans Soc Pathol Jpn. 1948;37(2):179–80.

Beccastrini E, Emmi G, Chiodi M, Di Paolo C, Silvestri EB, Massi D, et al. Kimura’s disease: case report of an Italian young male and response to oral cyclosporine A in an 8 years follow-up. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(1):55–7.

Osuch-Wójcikiewicz E, Bruzgielewicz A, Lachowska M, Wasilewska A, Niemczyk K. Kimura’s disease in a Caucasian female: a very rare cause of lymphadenopathy. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2014;2014:415865.

Rush ML, Mauro A, Bhansali P. Kimura disease: a case report of a rare illness presenting as a common complaint. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(4):393–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2018-0096.

Monzen Y, Kiya K, Nishisaka T. Kimura’s disease of the orbit successfully treated with radiotherapy alone: a case report. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2014;5(1):87–91.

Lee JH, Kim JH, Lee SU, Kim SC. Orbital mass with features of both Kimura disease and immunoglobulin G4-related disease. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34(4):e121–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000001135.

Ting SL, Zulkarnaen M, Than TA. Diagnostic dilemma of kimura disease of eyelids. Med J Malaysia. 2020;75(1):83–5.

Yamamoto T, Minamiguchi S, Watanabe Y, Tsuji J, Asato R, Manabe T, et al. Kimura disease of the epiglottis: a case report and review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8(2):198–203.

Yeh S, Lee W, Hu C, Tsai H. Kimura’s disease mimicking an earlobe keloid. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(4):e97–9.

Matsuo T, Tanaka T, Kinomura M. Nephrotic syndrome during the tapering of oral steroids after pathological diagnosis of Kimura disease from a lacrimal gland mass: case report and review of 10 Japanese patients. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2017;57(3):147–52. https://doi.org/10.3960/jslrt.17028.

Sah P, Kamath A, Aramanadka C, Radhakrishnan R. Kimura’s disease - an unusual presentation involving subcutaneous tissue, parotid gland and lymph node. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17(3):455.

Woo SH, Kim HK, Kim WS, Bae TH, Kim MK. A rare case of Kimura disease with bilateral parotid involvement. Arch Plast Surg. 2017;44(5):439–43. https://doi.org/10.5999/aps.2017.44.5.439.

Kabashima R, Kabashima K, Mukumoto S, Hino R, Huruno Y, Kabashima N, et al. Kimura’s disease presenting with a giant suspensory tumour and associated with membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19(6):626–8.

Kakkar A, Gupta RK, Khanna P, Balasundaram P, Ray R, Shukla NK. Kimura disease of the breast - a previously undescribed entity. Breast J. 2016;22(4):456–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.12603.

Chung Y-G, Jee W-H, Kang Y-K, Jung C-K, Park G-S, Lee A-h, et al. Kimura’s disease involving a long bone. Skelet Radiol. 2010;39(5):495–500.

Liu XK, Ren J, Wang XH, Li XS, Zhang HP, Zeng K. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia and Kimura's disease coexisting in the same patient: evidence for a spectrum of disease. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53(3):e47–50.

Choi WJ, Hur J, Ko JY, Yeo KY, Kim JS, Yu HJ. An unusual clinical presentation of Kimura’s disease occurring on the buttock of a five-year-old boy. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22(1):57–60.

Yuen H, Goh Y, Low W, Lim-Tan S. Kimura’s disease: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Singap Med J. 2005;46(4):179–83.

Birol A, Bozdoǧan Ö, Keleş H, Kazkayasi M, Bagci Y, Kara S, et al. Kimura’s disease in a Caucasian male treated with cyclosporine. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(12):1059–60.

Sun QF, Xu DZ, Pan SH, Ding JG, Xue ZQ, Miao CS, et al. Kimura disease: review of the literature. Intern Med J. 2008;38(8):668–72.

Caponetti GC, Miranda RN, Althof PA, Dobesh RC, Sanger WG, Medeiros LJ, et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular cytogenetic evaluation of potential targets for tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(12):2223–8.

Edelweiss M, Medeiros LJ, Suster S, Moran CA. Lymph node involvement by Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 20 cases. Hum Pathol. 2007;38(10):1463–9.

Shahryari J, Dabiri S, Talebi A. Kimura’s disease: a case report and review of literatures. Iran J Pathol. 2012;7(4):251–5.

Zhang X, Jiao Y. The clinicopathological characteristics of Kimura disease in Chinese patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(12):3661–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04752-6.

Kung IT, Gibson JB, Bannatyne PM. Kimura’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 21 cases and its distinction from angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Pathology. 1984;16(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.3109/00313028409067909.

Chow LT, Yuen RW, Tsui WM, Ma TK, Chow WH, Chan SK. Cytologic features of Kimura’s disease in fine-needle aspirates. A study of eight cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102(3):316–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/102.3.316.

Armstrong WB, Allison G, Pena F, Kim JK. Kimura’s disease: two case reports and a literature review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107(12):1066–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348949810701212.

Tsukadaira A, Kitano K, Okubo Y, Horie S, Ito M, Momose T, et al. A case of pathophysiologic study in Kimura’s disease: measurement of cytokines and surface analysis of eosinophils. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81(5):423–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)63139-0.

Gumbs MA, Pai NB, Saraiya RJ, Rubinstein J, Vythilingam L, Choi YJ. Kimura’s disease: a case report and literature review. J Surg Oncol. 1999;70(3):190–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199903)70:3<190::aid-jso9>3.0.co;2-a.

Okami K, Onuki J, Sakai A, Tanaka R, Hagino H, Takahashi M. Sleep apnea due to Kimura’s disease of the larynx. Report of a case. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2003;65(4):242–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000073125.

Chen H, Thompson LD, Aguilera NS, Abbondanzo SL. Kimura disease: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(4):505–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200404000-00010.

Chitapanarux I, Ya-In C, Kittichest R, Kamnerdsupaphon P, Lorvidhaya V, Sukthomya V, et al. Radiotherapy in Kimura’s disease: a report of eight cases. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90(5):1001–5.

Kilciksiz S, Calli C, Eski E, Topcugil F, Bener S. Radiotherapy for Kimura’s disease: case report and review of the literature. J BUON. 2007;12(2):277–80.

Meningaud JP, Pitak-Arnnop P, Fouret P, Bertrand JC. Kimura’s disease of the parotid region: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(1):134–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2005.10.043.

Shin ST, Yang YH, Chiang BL. Recurrent Kimura’s disease: report of one case. Acta Paediatr Taiwan. 2007;48(3):149–51.

Wang DY, Mao JH, Zhang Y, Gu WZ, Zhao SA, Chen YF, et al. Kimura disease: a case report and review of the Chinese literature. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;111(1):c55–61. https://doi.org/10.1159/000178980.

Soeria-Atmadja S, Oskarsson T, Celci G, Sander B, Berg U, Gustafsson B. Maintenance of remission with cyclosporine in paediatric patients with Kimura’s disease - two case reports. Acta Paediatr (Oslo, Norway: 1992). 2011;100(10):e186–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02259.x.

Wang Z, Zhang J, Ren Y, Dai Z, Ma H, Cui D, et al. Successful treatment of recurrent Kimura’s disease with radiotherapy: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(7):4519–22.

Hsu SN, Chang CF, Su TF, Hsu YC, Chen YA, Chen HC. Kimura’s disease associated necrotizing eosinophilic vasculitis presenting with recurrent peripheral arterial occlusive disease: a case report and review of the literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39(1):144–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-014-1085-2.

Ye X, Feng Y, Lin S. Pulmonary embolism as the initial clinical presentation of Kimura disease: case report and literature review. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015;26(4):414–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/mbc.0000000000000278.

Wang H, Fang F, Sun Y, Wang S, Mao Y. Concurrent Kimura disease and lupus nephritis: a case report. Medicine. 2016;95(41):e5086. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000005086.

Chakraborti C, Saha AK, Bhattacharjee A, Lakra R. Kimura’s disease involving bilateral lacrimal glands and extraocular muscles along with ipsilateral face: a unique case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(12):2107–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_810_19.

Li X, Wang J, Li H, Zhang M. Misdiagnosed recurrent multiple Kimura’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019;10(3):352–6. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2018.1793.

Zhang G, Li X, Sun G, Cao Y, Gao N, Qi W. Clinical analysis of Kimura’s disease in 24 cases from China. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-019-0673-7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81700410), the Sichuan Science and Technology Program, China (Grant No. 2019YFS0344). All the funds were granted to Dr. Jun Gu for the charge of article-processing charge, manuscript modifications and the follow-up fee of patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB: conception of the work; analysis and interpretation of data; draft of the manuscript. JG: conception of the work; analysis and interpretation of data; draft of the manuscript. CH: design of the work; the acquisition and interpretation of data; substantively revision. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parent or guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bi, S., Gu, J. & Hu, C. Kimura’s disease mimicking thoracic spine dumbbell neurogenic tumor: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg 20, 209 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00870-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00870-0