Abstract

Background

In cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery, postoperative complications remain major clinical problems. Early mobilization has been widely practiced and is an important component in preventing complications, including orthostatic hypotension (OH) during postoperative management. We investigated cardiovascular response during early mobilization and the incidence of OH after cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery.

Methods

In this prospective observational study, we consecutively analyzed data from 495 patients who underwent elective cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery. We examined the incidence of OH, and the independent risk factors associated with OH during early mobilization after major surgery. Multivariate logistic regression was performed using various characteristics of patients to identify OH-related independent factors.

Results

OH was observed in 191 (39%) of 495 patients. The incidence of OH in cardiac, thoracic, and abdominal groups was 39 (33%) of 119, 95 (46%) of 208, and 57 (34%) of 168 patients, respectively. Male sex (OR 1.538; p = 0.03) and epidural anesthesia (OR 2.906; p < 0.001) were independently associated with OH on multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that approximately 40% patients experience OH during early mobilization after cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery. Sex was identified as an independent factor for OH during early mobilization after all three types of surgeries, while epidural anesthesia was only identified after thoracic surgery. Therefore, the frequent occurrence of OH during postoperative early mobilization should be recognized.

Trial registration

University hospital Medical Information Network Center (UMIN-CTR) number UMIN000018632. (Registered on 1st October, 2008).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs, also known as fast-track surgery, are multimodal perioperative programs that aim to accelerate recovery, shorten hospital stay, and reduce postoperative complications. Postoperative management includes epidural anesthesia, early mobilization, early enteral nutrition, and early removal of catheters [1,2,3]. Early mobilization has been widely practiced and is an important component in preventing complications, including orthostatic hypotension (OH) during postoperative care [4, 5]. However, postoperative patients are frequently exposed to prolonged immobilization. Immobility has an important role in the development of neuromuscular weakness, atelectasis, insulin resistance, joint contractures, and OH [6,7,8]. In cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery, postoperative complications remain major clinical problems, despite advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care.

Postoperative OH is characterized by symptoms of dizziness, nausea, vomiting, or syncope during sitting or standing [9]. OH is a well-known clinical complication that can delay early mobilization, although relatively little data are available regarding its mechanism and possible treatment [10]. In addition, the pathophysiology of OH might be related to impaired cardiovascular regulation postoperatively [11], but this relationship is not clearly understood. Previous studies have documented a 12-19% rate of incidence of OH during early postoperative mobilization in patients who were treated for breast cancer, had undergone hip arthroplasty, or had received some type of gynecological treatment [12,13,14,15]. Only one study assessed the cardiovascular response and orthostatic intolerance to early mobilization after video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS). This study demonstrated a 35% incidence of OH [16].

More surgical stress is anticipated in cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery compared to those surgeries. Although, incidence of OH after cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery has not been well-known, we hypothesize that more OH should be identified after cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery. The primary aim of this study was to examine the incidence of OH during early mobilization after major surgery. In addition, we investigated the independent risk factors associated with OH.

Methods

Patients

As a prospective observational study, we enrolled patients who underwent cardiac surgery (cardiac group), thoracic surgery (thoracic group), and abdominal surgery (abdominal group) at Nagasaki University Hospital and Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital from October 2008 to January 2012. In each group covered in cardiac group (e.g., coronary heart disease, valve diseases), in thoracic group (e.g., lung cancer, mediastinal neoplasm), in abdominal group (e.g., gastric cancer, liver and pancreatic cancer), respectively. All patients received standard perioperative management and nursing care following the critical path. Patients were included if they were older than 18 years, were undergoing planned surgery, and could provide written informed consent. Patients were established to have a performance status of 0 and to be clinically stable before the surgery. Patients were excluded if they had comorbid conditions that affected exercise performance (e.g., musculoskeletal or neurological impairment); had undergone re-operation; off-pump cardiac surgery; were experiencing atrial fibrillation, vomiting, and diarrhea before mobilization; or had a history of any cerebrovascular disease and postoperative admission to the intensive care unit. The Human Ethics Review Committee of Nagasaki University Hospital (Approval number: 09022760 − 2) and Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital (Approval number: 09-02) approved this study.

Measurement

A physiotherapist evaluated cardiovascular response and symptoms during an attempt to perform a standing exercise on postoperative day 1 (POD 1). Systolic blood pressure (mmHg; SBP), diastolic blood pressure (mmHg; DBP) and mean arterial pressure (mmHg; MAP), heart rate (beats per minute; HR), oxygen saturation (percentage; SpO2), and respiratory rate (frequency per minutes; RR) were monitored throughout mobilization using the BSM-2300 series Life scope-i (Nihon Kohden Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Their values in a supine position were defined as the baseline levels. We evaluated patients in the supine position, while sitting on the edge of a bed (immediate, 3 and 5 min after), and while standing (immediate and 3 min after). For blood pressure measurements, a brachial cuff was placed around the left arm kept in a fixed position at heart level. HR was measured using an electrocardiogram of the same monitor. SpO2 was measured using a probe that attached to the right finger. OH and the cardiovascular response while the patients transitioned from sitting on the edge of the bed to standing were evaluated. Fluid balance was defined volume loss from start of anesthesia to the morning of the day of mobility.

Vasopressors included a postoperative continuous intravenous infusion of catecholamines (i.e., dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine). We calculated the catecholamine index (CAI) [17, 18], as follows, wherein all doses were expressed as μg/kg/min.

CAI = (dopamine dose × 1) + (dobutamine dose × 1) + (epinephrine dose × 100) + (noradrenaline dose × 100).

A selection of perioperative anesthetics and the use of thoracic epidural anesthesia were at the discretion of the attending anesthesiologist. Postoperative analgesics use included continuous intravenous infusion of fentanyl and epidural infusion of ropivacaine hydrochloride. For intravenous infusion of fentanyl, a Terufusion syringe pump TE-331S (TERUMO, Tokyo, Japan) was used. For epidural infusion anesthetics (ropivacaine 0.2%), Infuser SV4 (Baxter Limited, Tokyo, Japan) was used. The basal infusion rate was set at 4 ml/h.

Assessment of OH

OH was defined as a fall in SBP of at least 20 mmHg or a fall in DBP of at least 10 mmHg within 3 min upon standing and as intolerable dizziness, nausea and vomiting upon mobilization [9, 19]. Mobilization sessions were discontinued when the patients experienced an increase in symptoms until they returned to a sitting position (fainting, excessive pain, dizziness, nausea, sweating, pallor, and postoperative delirium) and when the patients could not measure at baseline vital sign.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was to clarify the incidence of OH during early postoperative mobilization after having undergone cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery and the relationship between early mobilization and cardiovascular response changes. The secondary outcome was to identify independent factors associated with OH by performing multivariate logistic regression.

Statistical analysis

Data were compared using a Wilcoxon’s rank sum test and Fisher’s exact test between cardiothoracic and abdominal groups. Wilcoxon’s rank sum test was performed for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test was performed for categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was then performed to correct for risk factors that showed at least a trend toward significance (P < 0.1) in the univariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify the dependent variables of orthostatic hypotension. Data are described as frequencies for categorical variables and as the median and interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 11.0 software (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

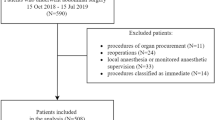

A total of 544 patients who had undergone cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery were evaluated in a prospective cohort study (Fig. 1). Since data of 49 patients were missing, they were excluded. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the patients. Four hundred ninety-five postoperative patients were categorized into cardiac group (n = 119, aged 74 IQR, 66-79 years), thoracic group (n = 208, aged 65 IQR, 58-73 years), and abdominal group (n = 168, aged 72 IQR, 64-78 years).

Coronary heart disease 38 (31.9%), valve diseases 57 (47.9%), aortic and vascular disease 24(20.2%) patients were included in cardiac group. Lung cancer 134 (64.4%), mediastinal neoplasm 12 (5.8%), esophageal cancer 39(18.8%), Other 23 (11.1%) patients were included in Thoracic group. Gastric cancer 33 (19.6%), colorectal cancer 9 (5.4%), liver and biliary system diseases 79 (47.0%), pancreatic cancer 47 (28.0%) patients were included in abdominal group.

Cardiovascular comorbidities included hypertension in 144 patients (29.1%), arrhythmia in 12 patients (2.4%), and angina pectoris in 5 patients (1.0%). Comorbidities of the respiratory system included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 12 patients (2.4%), asthma in 7 patients (1.4%), and interstitial lung disease in 5 patients (1.0%). Neurological system comorbidities included cerebrovascular disease in 5 (1.0%) patients. Orthopedic system comorbidities included vertebral compression fractures and lumbar spinal canal stenosis in 5 (1.0%) patients. Median preoperative ejection fraction in all patients was 70 (65 to 75). Figure 2 shows the cardiovascular response during postoperative mobilization. There were no significant differences in the cardiovascular response between the groups. There were significant differences in type of surgery (p = 0.02), analgesia with opioids (p = 0.02) and epidural anesthesia (p < 0.0001) between those with and without OH (Table 2).

One hundred and ninety-one (38.6%) of 495 patients exhibited OH. The incidence of OH was 39 (32.8%) of 119 in cardiac patients, 95 (45.7%) of 208 in thoracic patients, and 57 (33.9%) of 168 in abdominal patients. Forty-eight (25.1%) of 191 patients withdrew during postoperative mobilization. Of these 48 patients, seven (17.9%) of 39 patients had undergone cardiac surgery, 31 (32.6%) of 95 patients had undergone thoracic surgery, and 10 (17.5%) of 57 patients had undergone abdominal surgery (Fig. 3). Early mobilization was discontinued in 48 patients due to dizziness in 16 patients (33.3%), nausea in 15 patients (31.3%), wound pain in 9 patients (18.6%), and fatigue in 8 patients (16.7%). There was no significant correlation between discontinuation and the rate of variability in SBP (p = 0.74), DBP (p = 0.28), HR (p = 0.50) and MAP (p = 0.52).

There were significant differences in blood transfusion (p = 0.01), vasopressor (p = 0.02) and CAI (p = 0.01) between those with and without OH in the cardiac group. There were significant differences in fluid balance (p = 0.01), analgesia with opioids (p < 0.05) and epidural anesthesia (p < 0.001) between those with and without OH in the thoracic group. There were significant differences in operative time (p = 0.02), operative blood loss (p = 0.01), blood transfusion (p < 0.05), vasopressor (p < 0.05), and initial standing (p = 0.02) between those with and without OH in the abdominal group (Table 3).

According to the postoperative medication received, antihypertensive agents were prescribed to 29 (24.4%) patients, antiarrhythmic agents to 24 (20.2%) patients in cardiac group. These medications were no significant differences in the cardiovascular response between the groups. Nineteen (16.0%) of 119 patients in the cardiac group received postoperative continuous intravenous infusion of fentanyl, with the median rate of infusion being 25 μg/h (IQR, 25-50 μg/h). Of the 208 thoracic surgery patients, 130 (62.5%) patients received a continuous postoperative epidural infusion of ropivacaine, with the median rate of infusion being 8 μg/h, and 57 (27.4%) received fentanyl, with the median rate of infusion being 50 μg/h (IQR, 50-50 μg/h). Of the 168 abdominal patients, 141 (83.9%) received fentanyl with the median rate of infusion being 50 μg/h (IQR, 28-50 μg/h).

In a univariate analysis of the following parameters, the type of surgery, sex, age, body mass index, preoperative ejection fraction, fluid balance, operative time, blood loss, the value of hemoglobin and serum creatinine measured on POD 1, CAI, the use of vasopressors, analgesia with opioids, and epidural anesthesia showed a significant relationship with OH.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated an independent association between the incidence of OH and male sex (Odds ratio (OR); 1.538, 95% CI, 1.027 to 2.326; p = 0.03) or receiving epidural anesthesia (OR; 2.906, 95% CI, 1.924 to 4.419; p < 0.001; Table 4).

Discussion

The main findings of the present study in patients who had undergone cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery, we found that (1) 38.6% experienced OH during early mobilization after surgery and (2) men and patients who received an epidural anesthesia were predisposed to experience OH during early mobilization.

The results suggest that the range of variation in the cardiovascular responses during postoperative mobilization is limited, and we did not recognize an association between the cardiovascular response and symptoms. In general, postoperative patients are particularly vulnerable upon mobilization aggravate the postural reduction in central blood volume in the upright position [20]. However, a previous study also indicated that there was no relationship between postoperative symptoms and cardiovascular response during early mobilization [21]. Our results were consistent with those of the previous report. Therefore, it is important to assess the subjective symptoms of patients in addition to measuring cardiovascular response during mobilization.

The incidence of OH and the use of postoperative opioids were higher than in previous studies [12,13,14,15,16], and a quarter of patients discontinued from the study. Approximately 60% of cases that discontinued early mobilization were due to dizziness and nausea. In general, the use of postoperative opioids is associated with an increased risk of nausea and vomiting, thus resulting in an increase in the incidence and severity of OH [15, 22]. Although it is reasonable to assume that both epidural analgesia and analgesia with opioids are the causes of OH, we found that only epidural anesthesia was associated with an increased risk of OH. The use of epidural anesthetics theoretically induces OH through sympathectomy-induced vasodilation [16]. Gramigni E et al. [23] reported cardiovascular response during postoperative mobilization that involved the use of thoracic epidural analgesia with a mixture of bupivacaine and fentanyl. They concluded that epidural analgesia was associated with arterial hypotension during the postoperative period. Although we agree with their opinion, our results identified that epidural analgesia without opioids was an independent predisposing factor for OH. However, it is difficult to be certain of the relationship between epidural analgesia and OH based upon the results of this study only. Overall, when employing early mobilization, clinicians and physiotherapists should be careful when postoperative patients use analgesics to treat OH. As discussed above, many studies offer different perspectives; however, it is approximately certain that analgesics influence the incidence of OH. Since most patients use analgesics after surgery, clinicians should take precautions when mobilizing these patients. Furthermore, physiotherapists should advise patients to be in Fowler’s position and wear elastic stockings during the day to reduce the risk of OH [24]. Early mobilization using various devices is important for prevention of orthostatic intolerance, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary complications.

In the cardiac group, rigorous postoperative management was required to prevent heart failure and postoperative bleeding such as open aortic surgery and heart valve surgery. In this study, 55% of vasopressor use occurred in the cardiac group. When we evaluated the rate of OH and discontinuation in the cardiac group, the use of vasopressor might not have influenced the relationship between orthostatic cardiovascular responses, although vasopressor use and the CAI were significantly different between the groups with and without OH. It is reasonable for us to anticipate that the incidence of OH would be increasing without vasopressor use; however, in our results, OH was more prevalent in patients using vasopressors. Therefore, it was difficult to assess the influence of vasopressor use in the cardiac surgery group. Also, antihypertensive and antiarrhythmic agents were used in cardiac group. Although, these medicines were no significant differences in the cardiovascular response between the groups, we should continue to evaluate the relationship between these medicines use and OH development.

OH was observed more frequently in the thoracic group. Epidural anesthesia was shown to be an independent predisposing factor for OH development in multivariate analysis, and it was used only in this group. Mizota et al. [16] found that postoperative opioid use were independent risk factors for OH after VATS. In addition, they demonstrated that continuous postoperative epidural administration of ropivacaine at 0.2% at a rate of 2-6 ml/h did not induce clinically significant vasodilation. In our study, we applied epidural anesthesia using a continuous postoperative epidural administration of the same dose of ropivacaine. In doing so, we found that its use was an independent predisposing factor for OH. Thus, we observed a different result from that of the previous study. Therefore, in the future, we will attempt to clarify the influence of epidural anesthesia on the development of OH.

In the abdominal group, operative factors might not be associated with OH between patients with and without OH. Haines KJ et al. [25] concluded that 52% of patients undergone high-risk abdominal surgery had a barrier to mobilization, with the most common barrier being hypotension. In our study, we did not detect a relationship between blood pressure and OH. It was difficult to anticipate OH using only the cardiovascular response in patients who had undergone abdominal surgery. Future studies should include physiological parameters to predict the incidence of OH in patients who had undergone abdominal surgery.

The male was independently associated with the incidence of OH. Convertino [26] demonstrated that fluid volume shifting during postural changes had been lower in females than in males. Females are at an increased risk for OH as a result of common variables related to body size and hormones [27]. However, our results did not show similar results, which may possibly be due to two reasons. First, our subjects were postoperative patients. Surgical trauma imposes increased demands on organs with increased sympathetic tone and a subsequent endocrine metabolic response. In addition, blood loss and fluid volume shifts that might occur might influence the cardiovascular response to mobilization [20]. Second, in our subjects, more males were enrolled than females. These differences may also be related to muscle volume and body size. Therefore, our results suggest that male postoperative patients might experience orthostatic hypotension due to increased muscle sympathetic and peripheral blood vessel outflow due to muscle contraction. Currently, sex differences in OH have been observed, but the mechanisms are still unknown [27].

This study had several limitations. First, we investigated different types of surgeries because we wanted to capture the characteristics of each surgery. The mechanism of fluid shifts of each groups are probably heterogeneous due to complicated and diverse group of patients. However, the reason for targeting patients at postoperative course of thoracic and abdominal surgery is justified because these surgeries have an influence on autonomic nervous system and OH of postoperative complications are most likely to occur. Therefore, it was considered important to assess the cardiovascular response and orthostatic intolerance during mobilization after these postoperative surgeries. Second, we evaluated the phenomenon of hypotension under a clinical setting. Anatomical physiological details were unknown. Further studies are necessary to clarify these limitations.

Conclusion

The present study found a high incidence of OH during early mobilization in patients who had undergone cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery. Two independent predisposing factors for OH (male sex, and epidural anesthesia in thoracic surgery) were identified. In conclusion, it should be recognized that OH occurs frequently during postoperative early mobilization.

Abbreviations

- CAI:

-

Catecholamine index

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- ERAS:

-

Enhanced recovery after surgery

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- OH:

-

Orthostatic hypotension

- POD:

-

Postoperative day

- PPCs:

-

Postoperative pulmonary complications

- RR:

-

Respiratory rate

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SpO2:

-

Oxygen saturation

- VATS:

-

Video-assisted thoracic surgery

References

Eskicioglu C, Forbes SS, Aarts MA, Okrainec A, McLeod RS. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs for patients having colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2321–9.

Kaibori M, Matsui K, Ishizaki M, Iida H, Yoshii K, Asano H, et al. Effects of implementing an "enhanced recovery after surgery" program on patients undergoing resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Today. 2017;47:42–51.

Balzano G, Zerbi A, Braga M, Rocchetti S, Beneduce AA, Di Carlo V. Fast-track recovery programme after pancreatico- duodenectomy reduces delayed gastric emptying. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1387–93.

Browning L, Denehy L, Scholes RL. The quantity of early upright mobilisation performed following upper abdominal surgery is low: an observational study. Aust J Physiother. 2007;53:47–52.

Mackay MR, Ellis E, Johnston C. Randomised clinical trial of physiotherapy after open abdominal surgery in high risk patients. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51:151–9.

Hamburg NM, McMackin CJ, Huang AL, Shenouda SM, Widlansky ME, Schulz E, et al. Physical inactivity rapidly induces insulin resistance and microvascular dysfunction in healthy volunteers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2650–6.

Clavet H, Hebert PC, Fergusson D, Doucette S, Trudel G. Joint contracture following prolonged stay in the intensive care unit. CMAJ. 2008;178:691–7.

Kortebein P, Ferrando A, Lombeida J, Wolfe R, Evans WJ. Effect of 10 days of bed rest on skeletal muscle in healthy older adults. JAMA. 2007;297:1772–4.

Grubb BP. Neurocardiogenic syncope and related disorders of orthostatic intolerance. Circulation. 2005;111:2997–3006.

Jans Ø, Kehlet H. Postoperative orthostatic intolerance: a common perioperative problem with few available solutions. Can J Anaesth. 2016. doi:10.1007/s12630-016-0734-7.

Jans Ø, Brinth L, Kehlet H, Mehlsen J. Decreased heart rate variability responses during early postoperative mobilization--an observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:120. doi:10.1186/s12871-015-0099–4.

Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Jørgensen CC, Jørgensen TB, Ruhnau B, Secher NH, Kehlet H. Orthostatic intolerance and the cardiovascular response to early postoperative mobilization. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:756–62.

Müller RG, Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Kehlet H. Orthostatic function and the cardiovascular response to early mobilization after breast cancer surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:298–304.

Jans Ø, Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Solgaard S, Johansson PI, Kehlet H. Orthostatic intolerance during early mobilization after fast-track hip arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:436–43.

Iwata Y, Mizota Y, Mizota T, Koyama T, Shichino T. Postoperative continuous intravenous infusion of fentanyl is associated with the development of orthostatic intolerance and delayed ambulation in patients after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. J Anesth. 2012;26:503–8.

Mizota T, Iwata Y, Daijo H, Koyama T, Tanaka T, Fukuda K. Orthostatic intolerance during early mobilization following video-assisted thoracic surgery. J Anesth. 2013;27:895–900.

Tsujimoto H, Ono S, Hiraki S, Majima T, Kawarabayashi N, Sugasawa H, et al. Hemoperfusion with polymyxin B-immobilized fibers reduced the number of CD16+ CD14+ monocytes in patients with septic shock. J Endotoxin Res. 2004;10:229–37.

Cruz DN, Antonelli M, Fumagalli R, Foltran F, Brienza N, Donati A, et al. Early use of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in abdominal septic shock: the EUPHAS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:2445–52.

Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, pure autonomic failure, and multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1996;144:218–219.

Crawford ME, Møiniche S, Orbaek J, Bjerrum H, Kehlet H. Orthostatic hypotension during postoperative continuous thoracic epidural bupivacaine-morphine in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:1028–32.

Pusch F, Berger A, Wildling E, Tiefenthaler W, Krafft P. The effects of systolic arterial blood pressure variations on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1652–5.

Roberts GW, Bekker TB, Carlsen HH, Moffatt CH, Slattery PJ, McClure AF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting are strongly influenced by postoperative opioid use in a dose-related manner. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1343–8.

Gramigni E, Bracco D, Carli F. Epidural analgesia and postoperative orthostatic haemodynamic changes: observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013;30:398–404.

Juraschek SP, Daya N, Rawlings AM, Appel LJ, Miller ER 3rd, Windham BG, et al. Association of History of dizziness and long-term adverse outcomes with early vs later orthostatic hypotension assessment times in middle-aged adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;24. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2937.

Haines KJ, Skinner EH, Berney S, Austin Health POST Study Investigators. Association of postoperative pulmonary complications with delayed mobilisation following major abdominal surgery: an observational cohort study. Physiotherapy. 2013;99:119–25.

Convertino VA. Gender differences in autonomic functions associated with blood pressure regulation. Am J Phys. 1998;275:1909–20.

Cheng YC, Vyas A, Hymen E, Perlmuter LC. Gender differences in orthostatic hypotension. Am J Med Sci. 2011;342:221–5.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Terumitsu Sawai and Takako Tanaka, from Unit of Rehabilitation Sciences, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Nagasaki University, for study concept and design advice. The authors thank all of the staff who acquired data for study: Yudai Yano; Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Nagasaki University Hospital: Naoki Mio; Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Hiroshima University Hospital: Issei Natsui; Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Nagasaki Harbor Medical Center City Hospital: Masaki Oomagari, Kyohei Ito, Takeo Kimura at Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The authors do not wish to share our data, because the patients’ who participated this study did not agree to share their individual data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH, YT, YM, MO and RK planned the study. MH, YM, MO collected the data. MH, TM, SS performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. MH, HN, KE, TN, SE, RK convinced of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Human Ethics Review Committee of Nagasaki University Hospital (Approval number: 09022760-2) and Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital (Approval number: 09-02) approved this study. Participants gave written informed consent for analysis and publication prior to the study scenario. This study was registered in UMIN-CTR (UMIN000018632).

Consent for publication

All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanada, M., Tawara, Y., Miyazaki, T. et al. Incidence of orthostatic hypotension and cardiovascular response to postoperative early mobilization in patients undergoing cardiothoracic and abdominal surgery. BMC Surg 17, 111 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-017-0314-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-017-0314-y