Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies examining the association between β-carotene intake and risk of fracture have reported inconsistent findings. We conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the association between β-carotene intake and risk of fracture.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library databases for relevant articles that were published until December 2019. We also identified studies from reference lists of articles identified from the clinical databases. The frequentist and Bayesian random-effects model was used to synthesize data.

Results

Nine studies with a total of 190,545 men and women, with an average age of 59.8 years, were included in this meta-analysis. For β-carotene intake (1.76–14.30 mg/day), the pooled risk ratio (RR) of any fracture was 0.67 (95% Credible Interval (CrI): 0.51–0.82; heterogeneity: P = 0.66, I2 = 0.00%) and 0.63 (95%CrI: 0.44–0. 82) for hip fracture. By study design, the pooled RRs were 0.55 (95% CrI: 0.14–0.96) for case-control studies and 0.82 (95% CrI: 0.58–0.99) for cohort studies. By geographic region, the pooled RRs were 0.58 (95% CrI: 0.28–0.89), 0.86 (95% CrI: 0.35–0.1.37), and 0.91(95% CrI: 0.75–1.00) for studies conducted in China, the United States, and Europe, respectively. By sex, the pooled RRs were 0.88 (95% CrI: 0.73–0.99) for males and 0.76 (95% CrI, 0.44–1.07) for females. There was a 95% probability that β-carotene intake reduces risk of hip fracture and any type of fracture by more than 20%.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis suggests that β-carotene intake was inversely associated with fracture risk, which was consistently observed for case-control and cohort studies. Randomized controlled trials are warranted to confirm this relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoporotic fractures are widely recognized as a major public health problem in the elderly [1, 2]. Approximately, the incidence of osteoporotic fracture affects 25% of females and 10% of males aged 60 years or above [3,4,5]. In 2000, there were an estimated 9 million osteoporotic fractures among individual’s ≥ 50 years worldwide, of which 1.6 million were hip, 1.7 million were forearm, and 1.4 million were clinical vertebral fractures [6]. Osteoporotic fractures are associated with an increased risk of mortality [7], chronic pain, loss of physical function, and ultimately decreased quality of life, financial burden, and psychosocial consequences, which significantly affect the individual as well as the family and community. As the average age of the world’s population continues to rise at an unprecedented rate, osteoporotic fractures will undoubtedly impact larger proportions of the population. Osteoporotic fractures have major implications among the aging population as it is associated with high morbidity and mortality [8, 9]. Annually, close to 65,000 deaths occurred due to complications of osteoporotic fractures [10]. In addition, osteoporotic fractures may result in functional loss and consequently disabilities, which further impose a considerable economic burden on society [8, 9, 11]. This impact is projected to increase over the next decades due to the increasing aging population [12].

Nutrition is an important modifiable factor influencing bone health [13]. Dietary intake of nutrients is a nonpharmacological intervention strategy for preventing the reduction of the loss of bone quality and the incidence of fractures. Several studies have investigated the effect of nutrition on bone health [13]. Fruit and vegetables are major sources of β-carotene antioxidants, which have bone health properties. A meta-analysis based on five prospective studies and two case-control studies reported that hip fracture risk decreased by 28% among participants with higher (vs. lower) dietary consumption of total carotenoids and β-carotene [14]. Carotene may reduce fracture risk by counteracting oxidative stress, which also can adversely affect bone mineral density [15,16,17,18].

The association between dietary β-carotene intake and fracture risk has been examined by several studies. Ambrosini et al. conducted a large cohort study that found a significant decrease in overall fracture risk (Relative Risk 0.89, 95% Confidence Interval 0.82–0.97) for β-carotene intake [19]. A study in China indicated that higher dietary intake of β-carotene was associated with lower risk of hip fracture in middle-aged and elderly adults, specifically with a 61% decreased in odds of hip fracture (95% CI 0.31, 0.49) [18]. Moreover, a number of studies consistently found that high β-carotene intake is associated with a protective relationship with fracture risk [17, 18, 20, 21], but not all [22,23,24]. Therefore, this meta-analysis aims to investigate the association between β-carotene intake and risk of fracture using a Bayesian hierarchical random effect model.

Methods

The meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [25].

Study selection

We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane library databases for relevant studies that were published until December 2019. The medical subject headings (MeSH) used for the search were: “β-carotene” OR “Carotenoids” OR “Vitamin A” OR “Carotene” AND “Bone fracture” OR “Fracture” OR “Osteoporosis.” Reference lists from published articles identified from the clinical databases were also utilized to identify other relevant studies. Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) were written in the English language; (2) were original human studies; (3) had as the exposure of interest, β-carotene; (4) had as the outcome, fractures; and (5) provided risk estimates for the association between β-carotene and fractures.

Data extraction

Two investigators (TGC and SY) independently extracted all relevant articles and identified eligible studies. During data evaluation, any disagreements were resolved through discussion. The following information were extracted from each included study: first author, publication year, country of origin, study design, the percent of women, mean age of the participants, risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs, fracture outcomes, exposure assessment methods, and the full list of covariate adjustments.

Quality assessment

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of each individual study [26]. This scale assigns a maximum of nine stars to the following parameters: selection, comparability, exposure, and outcome. Studies with six star-items or less were considered as low quality, while those with at least seven star-items were considered as high quality.

Statistical analysis

We converted the RRs to the logarithmic scale, and pooled these RRs using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effect models [27]; random effect models account for both within- and between- study variations. These results are presented in forest plots. Bayesian hierarchical models were used to perform the random-effects meta-analysis. We employed the Bayesian approach for its flexibility and ability to model a small number of studies [28]. It also accounts for the uncertainty of the parameters of interest, which is particularly important when data is sparse [29]. The probabilities of the exposure effect cannot be calculated with frequentist analyses since parameters of interest (i.e. RR) are treated as fixed. Moreover, Bayesian analyses allow prior information about the exposure effect to be incorporated with the current data (likelihood) to become the posterior distribution. The natural logarithmic of the RR follows a normal distribution with effect size (θi) and within-study variance (δi2). It is mandatory to specify prior distributions in the Bayesian Model. We applied three different prior distributions to the model. First, we applied the non-informative prior [30], which assigns equal likelihood on all possible values of the θi (i.e. we set RR equal to 1.0, with a large variance). The second prior was the skeptical prior distribution [31, 32], where we allowed only a 5% chance to observe a 10% risk change on fracture among β-carotene intake. Lastly, for the enthusiastic prior distribution, we assumed that β-carotene intake decreases 50% risk of fracture by half. A uniform distribution (0, 10) and an inverse gamma distribution (0.1, 0.001) were used for between-study variance (τ2).

In addition, subgroup analyses were performed based on study design, geographical region of the study population, sex, and by the site of fracture. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q-statistic test and inconsistency was quantified by the I2 statistic [33]. The Egger’s tests were performed to identify any possible evidence of publication bias [34]. All analyses were performed using the WinBUGS program (Version 1.4.3, MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) and the R program (Version: 3.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study characteristics

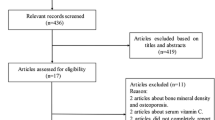

A flow chart summarizing the process of study selection is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 343 articles were identified from the electronic database search. Of these, 230 articles were excluded due to duplicates and unrelated titles. After screening, 88 articles were excluded based on titles and abstracts that were irrelevant to our study aim. Finally, 9 articles with a total of 190,545 men and women were included in the final analysis. Out of these, three studies were performed in the United States (US) [17, 18, 24], one in Australia [19], three in China or Singapore [20, 21, 35], one in the Netherlands [36], and one in the United Kingdom [37] (Table 1). The participants’ age was in the range of 25 to 90 years (average age: 59.8 ± 10.2 years). NOS score ratings for the 9 studies ranged from 5 to 9-stars, with seven studies scoring 7+ stars. These seven studies were considered as high-quality based on their NOS score. The NOS scores for the 9 included studies in the present meta-analysis are shown in Table 1.

Association between β-carotene intake and fracture risk

The observed RR and 95% CI of each study are shown in Fig. 2. In the traditional meta-analysis approach, β-carotene intake (1.76–14.30 mg/day) was negatively associated with fracture risk (RR 0.63, 95% CI: 0.52–0.77). Statistically significant heterogeneity was observed for fracture risk across all included studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 94.1%).

Under the skeptical prior, β-carotene intake was associated with a 12% decrease in the risk of fracture (RR 0.88; 95% Credible Interval [CrI] 0.76–0.98). Inverse associations were also noted using the posterior probability distribution, specifically there was a 95% probability that β-carotene intake reduces the risk of any fracture by at least 20% (Table 2). A negative association between β-carotene intake and risk of hip fracture was found (RR 0.63; 95% CrI: 0.44–0.82), with a significant heterogeneity across studies (p < 001, I2 = 91.8%; Figure S1).

Subgroup analyses

In subgroup analyses, the pooled RR for the association between β-carotene and fracture risk was 0.82 (95% CrI: 0.58–0.99) in cohort studies and 0.55 (95% CrI: 0.14–0.96) in case-control studies, suggesting protective associations (Table 2). Statistically significant evidence of heterogeneity was found in cohort studies (p < 001, I2 = 81.2%), but not in case-control studies (p = 0.45, I2 = 0.0%; Fig. 3). By geographic region, the pooled RR between β-carotene and fracture risk was 0.58 (95% CrI: 0.28–0.89) for studies conducted in China/Singapore, 0.86 (95% CrI: 0.35–0.1.37) for studies in the US, and 0.91 (95% CrI: 0.75–1.00) for studies in Europe. Evidence of heterogeneity was observed across studies conducted in the US (p < 001, I2 = 92.2%) and in China/Singapore (p < 001, I2 = 97.3%), but not in Europe (p = 0.09, I2 = 47.7%; Figure S2). Subgroup analysis by sex resulted in a pooled RR of 0.88 (95% CrI: 0.73–0.99) for males and 0.76 (95% CrI: 0.44–1.07) for females for the association between β-carotene and fracture risk, which may indicate that β-carotene’s role in improving bone health may benefit females slightly more than males. Heterogeneity was observed for both sexes (Males: p < 001, I2 = 79.4%; Females: p < 001, I2 = 95.0%; Figure S3).

Publication bias

We did not observe asymmetry across the studies (Fig. 4). No significant evidence of publication bias was found using Egger’s test (P = 0.09) and Begg’s test (P = 0.19).

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we investigated the association between β-carotene intake and the risk of fractures utilizing 9 peer-reviewed studies consisting of 190,545 men and women. We found that dietary β-carotene intake (1.76–14.30 mg/day) was associated with a 12% reduction in risk of fractures. In addition, higher intake of β-carotene was associated with lower risk of hip fractures. The findings of our meta-analysis suggests that higher dietary intake of β-carotene may have a favorable role in the protection of fracture risk.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that synthesizes the relationship between β-carotene intakes, derived solely from dietary sources, with the risk of fractures. Our findings were consistent with the results of a previous meta-analysis published by Xu et al. [14] that concluded high intake of dietary β-carotene significantly decreased the risk of hip fracture by 28% (OR 0.72; 95% CI: 0.54–0.95). However, findings from the present meta-analysis were discordant with the recently published meta-analysis by Zhang et al. [38], which observed that higher β-carotene intake was weakly associated with increased risk of total fracture (RR 1.07; 95% CI: 0.97, 1.17), though the results were not statistically significant. The differences in the findings between our study and Zhang et al.’s may be due to the lower number of studies included by Zhang et al. [38]. Further, Zhang et al. [39] did not differentiate between the assessment measures of β-carotene, including serum, plasma, and dietary intake of β-carotene in their analysis, while our study focused solely on dietary β-carotene measures.

In the current meta-analysis, we also found an inverse association between β-carotene intake and risk of fracture across both prospective cohort and case-control studies. This may strengthen the robustness of our results. Regarding sex, we found a lower risk of fracture for females compared to males among high (vs low) β-carotene intakes. This may be a plausible result given hormonal differences between sexes. These results provide additional information beyond those published by the two meta-analyses [14, 38] that reported a null association between β-carotene intake and fracture risk in females, but not in males. Differing conclusions in sub-analyses by geographic region for the relationship between dietary β-carotene and factures are likely due to variations in the study populations, specifically with regard to genetics, diverse dietary habits that may be tailored to each culture, and lifestyle factors.

The underlying mechanism for the association between β-carotene intake and lower incidence of fracture risk remains unclear. However, some probable biological mechanisms have been proposed. A sufficient intake of vitamin A, including β-carotene, is essential for normal physiological activities [40] by affecting the growth hormone axis [41, 42]. Although, some evidence from animal studies suggest that antioxidant β-carotene contributes to the body’s defense against reactive oxygen species [43]. Thus, oxidative stress is thought to play an important role in the development of several chronic diseases, including osteoporotic fracture. Therefore, antioxidant β-carotene may have a beneficial effect against oxidative stress related to osteoporosis. β-carotene enhances osteoclastogenesis and reduces osteoblast apoptosis by stabilizing the β-catenin signaling pathway, which leads to a decrease in bone resorption [44,45,46]. In addition, carotenoids may interfere with growth factor receptor signaling by regulating IGF-1/IGFBP3, which is associated with cognitive function [47]. Impaired cognitive function is a known risk factor for falls and hip fractures [48].

There are some limitations in our meta-analysis. First, the β-carotene intake consumption level is not consistent between the identified studies. In addition, fruit and vegetable consumption patterns among countries are quite different. This might influence the reliability of our results. Second, the methods of β-carotene intake assessment across studies varied. Some studies assessed β-carotene using a validated food frequency questionnaire, while others used a questionnaire that was not. Third, the extracted RR was adjusted for differing sets of confounders between studies. Further, some of the potential confounding factors (i.e., age, physical activity, supplementary carotenoid intake, smoking, and vitamins) were not taken into account, which contributes to heterogeneity and sparse finding between individual studies. Lastly, our analysis was based on observational studies, which cannot determine a causal relationship between β-carotene and fractures.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis generated a pooled-RR using a novel Bayesian approach to assess the association between β-carotene intake and risk of fracture utilizing 9 peer-reviewed observational studies. We found that β-carotene intake was inversely associated with fracture risk, which was consistently observed in both case control and cohort studies. The observed findings support the role of β-carotene as a potential protective factor for fractures. High intake of fruit and vegetables that are rich in β-carotene antioxidants may be beneficial for bone health and may reduce the risk of fractures. It is recommended that randomized controlled trials are conducted to confirm the potential protective relationship we observed between β-carotene intake and fractures.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/ or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Danielson L, Zamulko A. Osteoporosis: A Review. S D Med. 2015;68(11):503–5, 507–9.

Yang KC, Wang ST, Lee JJ, Fann JC, Chiu SY, Chen SL, Yen AM, Chen HH, Chen MK, Hung HF. Bone mineral density as a dose-response predictor for osteoporosis: a propensity score analysis of longitudinal incident study (KCIS no. 39). QJM. 2019;112(5):327–33.

Ferguson GT, Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, Jenkins CR, Jones PW, Willits LR, Yates JC, Vestbo J, Celli B. Prevalence and progression of osteoporosis in patients with COPD: results from the towards a revolution in COPD health study. Chest. 2009;136(6):1456–65.

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA 3rd, Berger M. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(4):721–39.

Nguyen ND, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Residual lifetime risk of fractures in women and men. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(6):781–8.

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Alarkawi D, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR. Accelerated bone loss and increased post-fracture mortality in elderly women and men. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(4):1331–9.

Center JR NT, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet. 1999;353:878–82.

B.Y. Farahmand, K. Michaelsson, A. Ahlbom, S. Ljunghall, J.A. Baron, G. Swedish Hip Fracture Study. Survival after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 16(12) (2005) 1583–1590.

Randell AG, Nguyen TV, Bhalerao N, Silverman SL, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Deterioration in quality of life following hip fracture: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(5):460–6.

Dawson-Hughes B, Burge R, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 22(2007):465–75.

Col N, Braithwaite RS, Wong JB. Estimating hip fracture morbidity, mortality and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:364–70.

Woo EK, Han C, Jo SA, Park MK, Kim S, Kim E, Park MH, Lee J, Jo I. Morbidity and related factors among elderly people in South Korea: results from the Ansan geriatric (AGE) cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:10.

Mitchell PJ, Cooper C, Dawson-Hughes B, Gordon CM, Rizzoli R. Life-course approach to nutrition. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(12):2723–42.

Xu J, Song C, Song X, Zhang X, Li X. Carotenoids and risk of fracture: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8(2):2391–9.

Tucker KL, Hannan MT, Chen H, Cupples LA, Wilson PW, Kiel DP. Potassium, magnesium, and fruit and vegetable intakes are associated with greater bone mineral density in elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(4):727–36.

Xie HL, Wu BH, Xue WQ, He MG, Fan F, Ouyang WF, Tu SL, Zhu HL, Chen YM. Greater intake of fruit and vegetables is associated with a lower risk of osteoporotic hip fractures in elderly Chinese: a 1:1 matched case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(11):2827–36.

Sahni S, Hannan MT, Blumberg J, Cupples LA, Kiel DP, Tucker KL. Inverse association of carotenoid intakes with 4-y change in bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Framingham osteoporosis study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(1):416–24.

Zhang J, Munger RG, West NA, Cutler DR, Wengreen HJ, Corcoran CD. Antioxidant intake and risk of osteoporotic hip fracture in Utah: an effect modified by smoking status. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(1):9–17.

Ambrosini GL, Bremner AP, Reid A, Mackerras D, Alfonso H, Olsen NJ, Musk AW, de Klerk NH. No dose-dependent increase in fracture risk after long-term exposure to high doses of retinol or beta-carotene. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(4):1285–93.

Sun LL, Li BL, Xie HL, Fan F, Yu WZ, Wu BH, Xue WQ, Chen YM. Associations between the dietary intake of antioxidant nutrients and the risk of hip fracture in elderly Chinese: a case-control study. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(10):1706–14.

Cao WT, Zeng FF, Li BL, Lin JS, Liang YY, Chen YM. Higher dietary carotenoid intake associated with lower risk of hip fracture in middle-aged and elderly Chinese: a matched case-control study. Bone. 2018;111:116–22.

de Jonge EA, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Campos-Obando N, Booij L, Franco OH, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Rivadeneira F, Zillikens MC. Dietary vitamin a intake and bone health in the elderly: the Rotterdam study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(12):1375.

WangR DZ, Ang LW, Low YL, Yuan JM, Koh WP. Protective effects of dietary carotenoids on risk of hip fracture in men: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:408–17.

Feskanich D, Singh V, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Vitamin A intake and hip fractures among postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;287(1):47–54.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. URL: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2009;172(1):137–59.

Greenland S. Bayesian perspectives for epidemiological research. II. Regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:195–202.

Sutton A, Lambert PC, Burton PR, et al. How vague is vague? A simulation study of the impact of the use of vague prior distributions in MCMC using WinBUGS. Stat Med. 2005;24:2401–28.

Spiegelhalter D, Higgins JP. Being skeptical about meta-analyses: a Bayesian perspective on magnesium trials in myocardial infarction. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:96–104 Community Health.

Abrams K, Spiegelhalter DJ, Myles JP. Bayesian approaches to clinical trials and health-care evaluation. Chichester: Wiley; 2004.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Egger MD, Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Chen GD, Zhu YY, Cao Y, Liu J, Shi WQ, Liu ZM, Chen YM. Association of dietary consumption and serum levels of vitamin a and beta-carotene with bone mineral density in Chinese adults. Bone. 2015;79:110–5.

Key TJ, Appleby PN, Spencer EA, Roddam AW, Neale RE, Allen NE. Calcium, diet and fracture risk: a prospective study of 1898 incident fractures among 34 696 British women and men. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(11):1314–20.

Hayhoe RPG, Lentjes MAH, Mulligan AA, Luben RN, Khaw K-T, Welch AA. Carotenoid dietary intakes and plasma concentrations are associated with heel bone ultrasound attenuation and osteoporotic fracture risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Norfolk cohort. Br J Nutr. 2017;117:1439–53.

Zhang X, Zhang R, Moore JB, Wang Y, Yan H, Wu Y, Tan A, Fu J, Shen Z, Qin G, Li R, Chen G. The effect of vitamin a on fracture risk: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(9).

Abrams K, Sanso B. Approximate Bayesian inference for random-effects meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1998;17(2):201–18.

Mellanby E. Vitamin a and bone growth: the reversibility of vitamin A-deficiency changes. J Physiol. 1947;105(4):382–99.

Djakoure C, Guibourdenche J, Porquet D, Pagesy P, Peillon F, Li JY, Evain-Brion D. Vitamin a and retinoic acid stimulate within minutes cAMP release and growth hormone secretion in human pituitary cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(8):3123–6.

Raifen R, Altman Y, Zadik Z. Vitamin A levels and growth hormone axis. Horm Res. 1996;46(6):279–81.

Stahl W, Sies H. Antioxidant activity of carotenoids. Mol Asp Med. 2003;24(6):345–51.

Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC. Quantifying osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis: challenges and rewards. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(10):1492–501.

Wang F, Wang N, Gao Y, Zhou Z, Liu W, Pan C, Yin P, Yu X, Tang M. Beta-carotene suppresses osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption by suppressing NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2017;174:15–20.

Wattanapenpaiboon N, Lukito W, Wahlqvist ML, Strauss BJ. Dietary carotenoid intake as a predictor of bone mineral density. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2003;12(4):467–73.

Kim Y, Lian F, Yeum KJ, Chongviriyaphan N, Choi SW, Russell RM, Wang XD. The effects of combined antioxidant (beta-carotene, alpha-tocopherol and ascorbic acid) supplementation on antioxidant capacity, DNA single-strand breaks and levels of insulin-like growth factor-1/IGF-binding protein 3 in the ferret model of lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(9):1847–54.

Landi F, Capoluongo E, Russo A, Onder G, Cesari M, Lulli P, Minucci A, Pahor M, Zuppi C, Bernabei R. Free insulin-like growth factor-I and cognitive function in older persons living in community. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2007;17(1):58–66.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was partly supported by a research start-up and a grant from the Education Department of Jilin, China (Grant number: JJKH20190090KJ to Y.S.) from Shuman Yang.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (TGC, YL, KSO, AMV and SY) significantly contributed to conception of study. TGC and SY designed the study. Literature search and analysis were performed by TGC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TGC; all authors (TGC, YL, KSO, AMV and SY) revised the manuscript and approved the final version of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication obtained from participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Forest plot of β-carotene intake and risk of hip fractures under the traditional meta-analysis approach

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

Forest plot of the association between β-carotene intake and risk of fracture under the traditional meta-analysis approach, stratified analysis by geographic region

Additional file 3: Figure S3.

Forest plot of observational studies examining the association between β-carotene intake and risk of fractures utilizing the traditional meta-analysis approach, stratified by sex

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Charkos, T.G., Liu, Y., Oumer, K.S. et al. Effects of β-carotene intake on the risk of fracture: a Bayesian meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21, 711 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03733-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03733-0