Abstract

Background

Comparative studies of total hip arthroplasty using the direct anterior approach (DAA) compared with the anterolateral approach (ALA) by gait analysis compared the results of the two groups, the damage to the abductor muscle, with objective and detailed kinematic as well as kinetic data of actual gait. The purpose of this systematic review was to analyze the differences in gait such as time-dependent parameters, kinetics, and kinematics after THA using the DAA compared with ALA.

Methods

PubMed Central, OVID Medline, Cochrane Collaboration Library, Web of Science, EMBASE and AHRQ carried out a comprehensive search for all relevant randomized controlled trials and comparative studies, up to December 2018. Based on the following criteria, studies were selected: 1) study design: randomized controlled trials or non-randomized comparative studies; 2) study population: patients with primary osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis; 3) intervention: total hip arthroplasty by DAA or ALA; 4) Kinetic and kinematic data after gait analysis in the plains during postoperative follow-up.

Results

Of the 148 studies, 7 randomized controlled trials and 5 comparative studies were finally included in this systematic review. The peak hip flexion within 3 months after surgery was described in two studies and was significantly higher in the DAA group. (OR = 1.90; 95% CI [1.67,2.13]; P < 0.01, Z = 16.18). The gait speed within 3 months after surgery was reported in 3 studies and was significantly higher in the DAA group than in the ALA group. (SMD = 0.17; 95% CI [0.12,0.22]; P < 0.01, Z = 6.62) There was no difference between the two groups in stride length, step length, and hip range of motion in sagittal plane.

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis, gait speed and peak hip flexion within 3 months after surgery were significantly higher in the DAA group than in the ALA group. Despite a few significant differences between two approaches, determining whether the reported differences in terms of postoperative gait values are clinically meaningful remains a substantial challenge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) reduces pain, and improves function and gait in patients with trauma or degenerative disease involving the hip joint [1]. The implant survival or patient-reported outcomes after THA via various surgical approaches yielded excellent results [2]. However, the survival of patients with the prosthesis is related to the type of bearing surface or the implant position. Therefore, the objective function of the patient cannot be determined using these assessment methods. In addition, the functional indicators of scores used in post-operative functional assessment do not adequately assess the functional status of the joint exercises actually used by the patient [3]. In this regard, gait analysis is a useful tool for the assessment of postoperative objective function after THA [4].

The direct anterior approach (DAA), which is used in THA, facilitates reaching the hip joint via intermuscular plane of the gluteus medius and sartorius. This surgical approach does not result in direct muscular damage and facilitates rapid recovery and early ambulation. [5]. It is technically demanding, however, with its own unique set of complications, which implies a significant period of learning [6]. Among the other approaches, an anterolateral approach (modified Harding, ALA) was performed to detach the gluteus medius and anterior one-third of the minimus to reach the hip joint and repair the muscle detached after insertion of the prosthesis [7]. Although the results are rapid and long-term follow-up is good, gait delay may occur due to muscle detachment and long-term functional challenges due to scar tissue formation or fatty degeneration [8, 9].

Comparative studies of THA results using both approaches reported the timing of gait, Harris hip score, complication rate, and radiological parameters [10]. These studies using gait analysis compared the results of the two groups, the damage to the abductor muscle, with objective and detailed kinematic as well as kinetic data of actual gait [7, 11, 12].

Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to analyze the differences in gait biomechanics such as time-dependent parameters, kinetics, and kinematics after THA using the DAA compared with the ALA.

Methods

Our current review and meta-analysis were performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13].

Study eligibility criteria

Studies were selected on the basis of the following criteria: 1) study design: randomized controlled trials or non-randomized comparative studies; 2) study population: patients with primary osteoarthritis or avascular necrosis; 3) intervention: total hip arthroplasty by DAA or ALA; 4) kinetic and kinematic data after gait analysis in the plains during postoperative follow-up.

Studies were excluded if 1) they failed to meet the above criteria; 2) patients were affected by orthopedic, neurological or other disease affecting gait pattern; and 3) gait analysis was performed using stairs.

Search methods for identification of studies

PubMed Central, OVID Medline, Cochrane Collaboration Library, Web of Science, EMBASE and AHRQ carried out a comprehensive search for all relevant randomized controlled trials and comparative studies, up to December 2018. We used the following search terms: “gait total hip approach”. A manual search of possibly related references was also conducted.(Additional file 1) Two researchers reviewed the titles, abstracts and full texts of all potentially relevant studies independently, as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration [14]. Any disagreement was resolved by the third reviewer. Full-text articles of the remaining studies were assessed according to the previously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, and then eligible articles were selected. The review authors were not blinded to authors, institutions, or the publication.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from the articles included: authors, date of publication, design of the study, participant features, follow-up period, specific interventions and outcome measurements. The outcomes pooled in this analysis included time distance parameters (gait speed, cadence, step length, step width, swing time), kinematics (hip joint range of motion, peak flexion or extension angle of hip joint during gait), and kinetics (hip moment). Kinetics was investigated but meta-analysis was not performed in this study because we did not get the data that can be used for statistical processing.

Methodological quality assessment

Two authors independently evaluated the methodological quality of the included studies using the same criteria for RCTs as described in the Cochrane Manual for Systematic Intervention Reviews 5.2. The 10 criteria were: 1) allocation concealment; 2) clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria; 3) the results of withdrawn or excluded patients after allocation were described and included in the intention to treatment analysis; 4) groups well matched, or with appropriate covariate adjustment; 5) surgeons’ experience; 6) identical care programs other than the trial options; 7) clearly defined outcome measures in the text with a definition of any ambiguous terms encountered; 8) blinding of outcome assessors to assignment status; 9) appropriate timing of outcome measures; and 10) reported follow-up loss less than 5 % of participants.

The scale between Newcastle and Ottawa was used to evaluate the methodological quality of non- randomized studies. It consists of eight items classified into three dimensions: the selection of the study population, the comparability of the groups and the determination of exposure (case-control study) or outcome (cohort study). Each dimension consists of subcategorized questions: selection (up to 4 stars), comparability (up to 2 stars) and exposure (up to 3 stars). A study can therefore be awarded up to 9 stars with the highest quality. The quality of all the studies was assessed independently by two authors.

Data analysis

In the included studies, the timing of gait analysis after total hip arthroplasty varied widely. So, we performed meta-analysis for the gait analysis performed within 3 months after THA to better clarify the differences between the two approaches. This meta-analysis was carried out with the software Review Manager (Rev Man 5.3) and the meaning was set to P < 0.05. For dichotomous results, the odds ratio (OR) and the confidence interval (CI) of 95% were calculated. For continuous outcomes, standardized mean difference (SMD) and CI was calculated at 95%. The heterogeneity size of the studies was estimated using I2 statistics and the Chi square test. A P of > 0.10 and an I2 of 50% were considered lacking statistical heterogeneity. Higgins I2 statistics was performed to test heterogeneity [15]. Significant heterogeneity was observed in these studies, and therefore, random effects or fixed effect models were adopted depending on the heterogeneity of the included studies. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by omitting a single study each time and building data from the remaining studies to explore possible high heterogeneity and to determine outcome stability.

Results

Search results

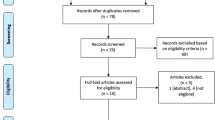

The initial search returned 148 references from the selected databases. The selection of abstracts and titles for duplicates, unrelated articles, case reports, systematic reviews and non- comparative studies excluded one hundred and twenty- eight references. The remaining 20 studies underwent full-text review. A further 3 studies were excluded. The details of the relevant studies can be found in the study selection process flow chart (Fig. 1). Seven randomized controlled studies and 5 comparative retrospective studies, including 429 patients (211 from DAA group, 218 from ALA group), were finally selected [1, 8, 12, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The main features and results of the meta-analyzed studies are shown in Table 1.

Gait speed

Three articles reported gait speed in the gait analysis performed within the postoperative 3 months [1, 8, 17]. A total of 66 patients were enrolled, including 39 patients in the DAA group and 27 patients in the ALA. A high degree of heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2 = 72, P = 0.03). Therefore, the random effects model was used for data analysis. A statistically significant higher gait speed was observed in the DAA group than in the ALA group (OR: 0.17, 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.22, P < 0.01, Z = 6.62) (Fig. 2).

Step length

Two studies performed gait analysis within 3 months postoperatively [1, 19]. A total of 53 patients were enrolled in the studies, including 30 patients in the DAA group and 23 patients in the ALA group. A high degree of heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I2 = 98, P < 0.01). Therefore, random effects model was used for data analysis. There was no statistically significant difference in step length within 3 months after THA between the two groups (OR: -0.01, 95% CI: -0.09 to 0.07, P = 0.82, Z = 0.23) (Fig. 3).

Stride length

Two studies reported stride length in gait analysis at 6 weeks postoperatively [1, 8]. A total of 46 patients were included, 27 in the DAA group and 19 in the ALA group. Significant heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2 = 97, P < 0.01). Therefore, a random effects model was used for data analysis. No statistically significant difference was evident in stride length within 6 weeks after THA between the two groups (OR: 0.05, 95% CI: -0.09 to 0.20, P = 0.46, Z = 0.73) (Fig. 4).

Peak hip flexion

Two studies reported peak hip flexion in gait analysis within 3 months postoperatively [1, 21]. A total of 103 patients were included, 55 in the DAA group and 47 in the ALA group. A low degree of heterogeneity was detected across studies (I2 = 0, P = 0.90). Therefore, a fixed effects model was used for data analysis. A statistically significant higher peak hip flexion was found in the DAA group than in the ALA group (OR: 1.90, 95% CI: 1.67 to 2.13, P < 0.01, Z = 16.18) (Fig. 5).

Hip range of motion (ROM) in sagittal plane

Two studies reported hip ROM in sagittal plane during gait analysis within 3 months postoperatively [8, 21]. A total of 103 patients were included, 52 in the DAA group and 41 in the ALA group. Significant heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2 = 98, P < 0.01). Therefore, a random effects model was used for data analysis. There was no statistically significant difference in hip ROM in sagittal plane within 3 months after THA between the two groups (OR: 6.20, 95% CI: -4.04 to 16.44, P = 0.24, Z = 1.19) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, gait speed and peak hip flexion within 3 months after surgery were significantly higher in the DAA group than in the ALA group, and there was no difference between the two groups in stride length, step length, and hip range of motion in sagittal plane.

Time distance parameter

During gait analyses within 16 weeks after operation, the time-distance parameters varied between the two groups (Table 2). Mayr and Klausmeier reported that in the gait analysis performed at 6 weeks postoperatively, the time-distance parameters were better in the DAA group [8, 16]. In addition, Mayr reported that the DAA group showed increased cadence, stride time and length, and walking speed at 12 weeks postoperatively, without any changes observed in the ALA group. Klausmeier reported that the time-distance parameters improved at 16 weeks postoperatively than at 6 weeks in both groups, although a significantly higher improvement was observed in the DAA group. However, in a study by Queen, Popsppischill, and Muller, gait analysis within 16 weeks after surgery showed no difference between the two groups, and Paliery reported that the swing phase of the affected limbs was significantly longer, without any significant differences in the remaining time-distance parameters [1, 18, 19, 22]. There was, however, no difference in time-distance parameters between the two groups during gait analysis after more than 10 months [12, 17, 22, 23]. In our meta-analysis, the gait speed within 3 months after surgery was superior to ALA group than DAA group. This suggests that the recovery of ambulatory function occurred much earlier in the DAA group than in the ALA group. However, as Varin et al. stated the time-distance parameters are not direct indicators of joint coordination, moment production, and force distribution, gait speed do not represent a direct function of the hip joint. Therefore, we should be careful when interpreting this result [24].

Hip kinetics and kinematics

In the short and long-term follow-up of gait analysis, the results of hip joint kinetics and kinematics were interpreted in various ways (Table 3). Mayr and Lugade et al. found a disparity in terms of gait analysis between the two groups, and DAA group showed faster recovery, and Kiss reported that Wesseling study gait analysis performed a year after operation revealed significantly greater improvement in gait in ALA close to normal gait and resulted in better functional outcome than in DAA group [16, 17, 21]. In our meta-analysis, the peak hip flexion within 3 months was significantly greater in the DAA group than in the ALA group. However, in the remaining studies, there was no difference in the results of gait analysis between the two groups, although a few data showed differences. However, caution is needed when interpreting the results of gait analysis in the above studies. Gait utilizes all the joints and muscles from the pelvis to the ankle, and therefore challenges associated with gait can be detected directly in the hip joint, although it can be observed in the form of compensation movement in the hip or other joints. The authors also believed that these differences were due to various forms of damage to the abductor, resulting in the difference between the two approaches.

Soft tissue injury

In the Wesseling study, there was a difference in hip flexion moment and abduction moment between the two groups [23]. In this study, no significant difference in loading was detected in the hip joint after one year of operation, but the hip flexion moment was lower in the ALA group than in the DAA group, and the hip abduction moment was lower in the DAA than in the ALA group. Meneghini et al. reported that 2.6% of the muscular area of the gluteus medius, 8.5% of the muscular area of the gluteus minimus, and 31.3% of the muscular area of the tensor fascia lata (TFL) were damaged during DAA in the cadaveric study [25]. Wesseling et al. asserted that gluteus minimus and medius are the main abductors of hip, and TFL is also a major hip abductor and DAA-induced TFL injury results in a decrease in hip abduction moment in the DAA group [23].

However, Varin et al. suggested that the peak hip abduction moment in the gait analysis at 10 months postoperatively was lower in DAA than in control or ALA, which may be attributed to female dominance [24]. In Palieri’s study, the gait analysis of the ALA group showed a decrease in hip flexion and abnormal EMG findings postoperatively at 10 days, suggesting that the anterior 1/3 of abductor muscle played a major role in hip flexion [22]. The reduction in hip flexion moment in the ALA group reflected abductor damage. In the Wesseling and Pospischill study, TFL injury in the DAA group showed that the degree of traction injury during surgery varied depending on the operator’s experience or skill [18, 23]. In Martin’s study, sufficient exposure of the femoral shaft through the DAA was considered a technical challenge [20]. Excessive tension on the posterior femoral neck by the Hohmann retractor may result in damage to the fibers of the gluteus medius around the insertion of the greater trochanter.

Gait mechanism of ALA group different from DAA group

In the systematic review, many studies have reported that ALA group shows different gait mechanisms compared to DAA group, which is thought to be caused by the difference in approach.

Pospischill et al. reported that one of the ALA group patients developed Trendelenburg gait 10 days postoperatively and disappeared around 12 weeks postoperatively [18]. In this study, 5 changes in the DAA group and 6 changes in the ALA group occurred. However, no change in the EMG of the TFL was detected in the DAA, although 2 statistically significant changes were found in the ALA group suggesting that ALA damages the abductor and TFL, and Trendelenburg gait was a compensatory mechanism to reduce hip joint loading. However, Pospischill et al. suggested possible soft tissue sparing with ALA because electromyogram (EMG) recovery was observed around 12 weeks [18].

Varin et al. also found that the pelvic ROM of the ALA group was 7.7 ° ± 2.4 °, which was not significantly different from the normal group; however, DAA presented with pelvic obliquity (8.4 ° ± 2.5 °) closer to normal range, which suggested an impact of the damaged abductor even though it failed to result in Trendelenburg gait [24]. By contrast, Mayr et al. reported that pelvic rotation in coronal plane and hip adduction in stance indicated abductor weakness; however, no significant changes in ALA group was observed at 6 and 12 weeks compared with DAA group [16]. Klausmeier et al. reported no changes in pelvic obliquity between the two groups at 6 weeks postoperatively [8]. However, these results may not be statistically significant due to the subtle change in pelvic obliquity and the lack of evaluation of compensation based on trunk kinematics. However, in the Palieri’s EMG analysis, chaotic timing of activation of gluteus medius was observed in the ALA group at 30 days postoperatively, and further hip flexion and minimal pelvic obliquity were observed in the ALA group at 90 days postoperatively, suggesting that recovery of the gluteus repair site after surgery may affect pelvic obliquity or hip flexion pattern [22].

The hip adduction moment increased in the ALA group. In the study by Queen et al., the ALA group exhibited a higher adduction moment compared with the unoperated hip, while a decreased hip adduction moment was observed in the DAA group compared with the unoperated hip. [12] Such outcome is probably due to the relative increase in adductor moment at the operative hip in patients included in the ALA group, which may have corresponded with pelvic drop during the propulsion phase. It may be attributed to weak abductor mechanism.

The internal rotation of hip joint and internal rotation of foot progression angle correlated with reduced abductor function. Abductor moment arm is compensated by internal rotation of hip in patients with reduced abductor function [26]. In the study by Mayr, the ALA group presented with increased maximum internal rotation of the hip in stance postoperatively after 6 weeks, and the increased hip flexion and ROM in the transverse plane, maximum internal rotation in stance at 12 weeks postoperatively, which was not observed in the DAA group [16]. This finding assumed that fatty atrophy of the anterior 1/3 of the gluteus medius by its anterior detachment leads to functional impairment and compensates for such impairment in ALA group. Muller et al. also state that anterior fiber of gluteus medius muscle also contributes to internal rotation and posterior fiber contributes to external rotation [9]. Therefore, the injury to the muscle of the abductor during ALA increased the external rotation of the lower limb, including the foot, in patients with complete gluteal insufficiency in the supine position. However, Muller et al. found a lack of significant difference in foot progression angle between DAA and ALA due to hypertrophy of TFL [27]. Martin et al. stated that ALA group was presented with internal rotation of foot progress angle compared with DAA group a year after operation and probably because femoral anteversion was not adequately evaluated [20].

Increased pelvic or knee motion occurred in the ALA group. Gait analysis during a year after operation showed that DAA group presented with gait pattern similar to the control group compared with ALA group. The study by Kiss showed that decreased hip motion in ALA group was compensated by another joint in the kinetic chain including knee motion and pelvic obliquity [21]. Increased pelvic obliquity and flexion-extension compensated for the decreased hip motion during the earlier post-operative period in ALA group, and was similar to the report by Miki et al. [28]. Huang et al. and Wu et al. also stated that pelvic rotation played an important role in increasing the step length during limited hip motion [29, 30]. In the study by Kiss, during the first postoperative month, the ALA group was unable to increase pelvic rotation because the gluteus medius and the posterior capsule were affected during surgery via ALA [21]. The significant decrease in step length of ALA group in the early postoperative months may be attributed to decreased hip motion and pelvic rotation. It can be hypothesized that in the late postoperative period the normal function of the gluteus medius and the posterior capsule was restored, facilitating increased pelvic rotation in the ALA group. Increased pelvic rotation resulted in step lengths that did not differ significantly from normal values despite decreased hip motion. Six months after surgery, the step length recovered to normal values with increased pelvic rotation, although hip motion was decreased.

The limitations of the study are as follows. First, this study lacked evaluation of preoperative mechanism of compensation for each study, which may have influenced postoperative gait analysis. In Klaumeier’s study, gait asymmetry in both groups at 16 weeks postoperatively was attributed to compensatory motion for osteoarthritis induced pain [8]. Petis’ study also referred to gait defect detected prior to operation [7]. Second, the recovery of strength and proprioception of injured muscle may vary with the different types of approach, and capsulotomy or capsulectomy affected the outcome [16, 31]. Third, the data of the included studies have heterogeneity. This is the limit of the meta-analysis, but we used a random model instead of a fixed model [32]. Forth, because the timing of gait analysis was varied, it did not include all the studies in each meta-analysis. Further studies will be needed in the future.

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis, gait speed and peak hip flexion within 3 months after surgery were significantly higher in the DAA group than in the ALA group, and there was no difference between the two groups in stride length, step length, and hip range of motion in sagittal plane. Despite a few significant differences between two approaches, determining whether the reported differences in terms of postoperative gait values are clinically meaningful remains a substantial challenge.

Abbreviations

- ALA:

-

Anterolateral approach

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DAA:

-

Direct anterior approach

- EMG:

-

Electromyogram

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

References

Queen RM, Butler RJ, Watters TS, Kelley SS, Attarian DE, Bolognesi MP. The effect of total hip arthroplasty surgical approach on postoperative gait mechanics. J Arthroplast. 2011;26:66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2011.04.033.

Sadoghi P, Liebensteiner M, Agreiter M, Leithner A, Böhler N, Labek G. Revision surgery after total joint arthroplasty: a complication-based analysis using worldwide arthroplasty registers. J Arthroplast. 2013;28:1329–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2013.01.012.

Nilsdotter A, Bremander A. Measures of hip function and symptoms: Harris hip score (HHS), hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS), Oxford hip score (OHS), Lequesne index of severity for osteoarthritis of the hip (LISOH), and American Academy of orthopedic surgeons (AAOS) hip and knee questionnaire. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(Suppl 11):S200–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20549.

Foucher KC, Freels S. Preoperative factors associated with postoperative gait kinematics and kinetics after total hip arthroplasty. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23:1685–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.005.

Meneghini RM, Smits SA, Swinford RR, Bahamonde RE. A randomized, prospective study of 3 minimally invasive surgical approaches in total hip arthroplasty: comprehensive gait analysis. J Arthroplast. 2008;23:68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2008.05.014.

Melman WPR, Mollen BP, Kollen BJ, Verheyen CCPM. First experiences with the direct anterior approach in lateral decubitus position: learning curve and 1 year complication rate. Hip Int J Clin Exp Res Hip Pathol Ther. 2015;25:251–7. https://doi.org/10.5301/hipint.5000221.

Petis S, Howard J, Lanting B, Jones I, Birmingham T, Vasarhelyi E. Comparing the anterior, posterior and lateral approach: gait analysis in total hip arthroplasty. Can J Surg J Can Chir. 2017;60:3217.

Klausmeier V, Lugade V, Jewett BA, Collis DK, Chou L-S. Is there faster recovery with an anterior or anterolateral THA? A pilot study. Clin Orthop. 2010;468:533–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-1075-4.

Müller M, Tohtz S, Springer I, Dewey M, Perka C. Randomized controlled trial of abductor muscle damage in relation to the surgical approach for primary total hip replacement: minimally invasive anterolateral versus modified direct lateral approach. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:179–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-010-1117-0.

Yue C, Kang P, Pei F. Comparison of direct anterior and lateral approaches in Total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA). Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2126. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002126.

Nishimura M, Takahira N, Fukushima K, Uchiyama K, Moriya M, Yamamoto T. Comparison of gait motion including postoperative trunk deflection between direct lateral and anterolateral approaches in supine Total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2016;31:1603–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.043.

Queen RM, Appleton JS, Butler RJ, Newman ET, Kelley SS, Attarian DE, et al. Total hip arthroplasty surgical approach does not alter postoperative gait mechanics one year after surgery. PM R. 2014;6:221–6; quiz 226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.09.006.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006.

Beaudet K. The cochrane collaboration and meta-analysis of clinical data. Am Orthopt J. 2010;60:6–8.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Mayr E, Nogler M, Benedetti M-G, Kessler O, Reinthaler A, Krismer M, et al. A prospective randomized assessment of earlier functional recovery in THA patients treated by minimally invasive direct anterior approach: a gait analysis study. Clin Biomech Bristol Avon. 2009;24:812–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.07.010.

Lugade V, Wu A, Jewett B, Collis D, Chou L-S. Gait asymmetry following an anterior and anterolateral approach to total hip arthroplasty. Clin Biomech Bristol Avon. 2010;25:675–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.05.003.

Pospischill M, Kranzl A, Attwenger B, Knahr K. Minimally invasive compared with traditional transgluteal approach for total hip arthroplasty: a comparative gait analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:328–37. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.01086.

Müller M, Schwachmeyer V, Tohtz S, Taylor WR, Duda GN, Perka C, et al. The direct lateral approach: impact on gait patterns, foot progression angle and pain in comparison with a minimally invasive anterolateral approach. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:725–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-012-1467-x.

Martin R, Clayson PE, Troussel S, Fraser BP, Docquier P-L. Anterolateral minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled study with a follow-up of 1 year. J Arthroplast. 2011;26:1362–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2010.11.016.

Kiss RM, Illyés Á. Comparison of gait parameters in patients following total hip arthroplasty with a direct-lateral or antero-lateral surgical approach. Hum Mov Sci. 2012;31:1302–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2012.02.004.

Palieri G, Vetrano M, Mangone M, Cereti M, Bemporad J, Roselli G, et al. Surgical access and damage extent after total hip arthroplasty influence early gait pattern and guide rehabilitation treatment. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;47:9–17.

Wesseling M, Meyer C, Corten K, Simon J-P, Desloovere K, Jonkers I. Does surgical approach or prosthesis type affect hip joint loading one year after surgery? Gait Posture. 2016;44:74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.11.009.

Varin D, Lamontagne M, Beaulé PE. Does the anterior approach for THA provide closer-to-normal lower-limb motion? J Arthroplast. 2013;28:1401–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2012.11.018.

Meneghini RM, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Hozack WJ. Muscle damage during MIS total hip arthroplasty: smith-Petersen versus posterior approach. Clin Orthop. 2006;453:293–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000238859.46615.34.

Arnold AS, Komattu AV, Delp SL. Internal rotation gait: a compensatory mechanism to restore abduction capacity decreased by bone deformity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:40–4.

Müller M, Tohtz S, Dewey M, Springer I, Perka C. Evidence of reduced muscle trauma through a minimally invasive anterolateral approach by means of MRI. Clin Orthop. 2010;468:3192–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1378-5.

Miki H, Sugano N, Hagio K, Nishii T, Kawakami H, Kakimoto A, et al. Recovery of walking speed and symmetrical movement of the pelvis and lower extremity joints after unilateral THA. J Biomech. 2004;37:443–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.09.009.

Huang YP, Bruijn SM, Lin JH, Meijer OG, Wu WH, Abbasi-Bafghi H, et al. Gait adaptations in low back pain patients with lumbar disc herniation: trunk coordination and arm swing. Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. 2011;20:491–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1639-8.

Wu WH, Meijer OG, Bruijn SM, Hu H, van Dieën JH, Lamoth CJC, et al. Gait in pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: amplitudes, timing, and coordination of horizontal trunk rotations. Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. 2008;17:1160–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-008-0703-0.

Madsen MS, Ritter MA, Morris HH, Meding JB, Berend ME, Faris PM, et al. The effect of total hip arthroplasty surgical approach on gait. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc. 2004;22:44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00151-7.

Yoon BH, Seo JG. Koo KH. Comparison of Postoperative Infection-Related Complications between Cemented and Cementless Hemiarthroplasty in Elderly Patients: A Meta-Analysis. 2017;9(2):145–52. https://doi.org/10.4055/cios.2017.9.2.

Acknowledgments

No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this study by any of the authors.

Funding

There is no funding source.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: YJI, CYH. Acquisition of data: CYH, YJI, KKJ, KHY. Analysis and interpretation: YJI, CWS, HSC. Study supervision: CWS, HSC. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board did not need approval for the design and protocol of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest. No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Detailed search strategies for each database. Mesh terms, search terms, and combinations of the two were used for each database search. (DOC 29 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, JI., Cha, YH., Kim, KJ. et al. Gait analysis after total hip arthroplasty using direct anterior approach versus anterolateral approach: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20, 63 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2450-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2450-2