Abstract

Background

Few studies have examined patterns of specific sleep problems among individuals with osteoarthritis (OA). The primary objective of this study was to examine prevalence of symptoms of insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) among Veterans with OA. Secondary objectives were to assess proportions of individuals with insomnia and OSA symptoms who may have been undiagnosed and to examine Veterans’ characteristics associated with insomnia and OSA symptoms.

Methods

Veterans (n = 300) enrolled in a clinical trial completed the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and the Berlin Questionnaire (BQ) at baseline; proportions of participants with symptoms consistent with insomnia and OSA were calculated, using standard cut-offs for ISI and BQ. For Veterans with insomnia and OSA symptoms, electronic medical records were searched to identify whether there was a diagnosis code for these conditions. Multivariable linear (ISI) and logistic (BQ) regression models examined associations of the following characteristics with symptoms of insomnia and OSA: age, gender, race, self-reported general health, body mass index (BMI), diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), pain severity, depressive symptoms, number of joints with arthritis symptoms and opioid use.

Results

Symptoms consistent with insomnia and OSA were found in 53 and 66% of this sample, respectively. Among participants screening positive for insomnia and OSA, diagnosis codes for these disorders were present in the electronic medical record for 22 and 51%, respectively. Characteristics associated with insomnia were lower age (β (SE) = − 0.09 (0.04), 95% confidence interval [CI] = − 0.16, − 0.02), having a PTSD diagnosis (β (SE) = 1.68 (0.73), CI = 0.25, 3.11), greater pain severity (β (SE) = 0.36 (0.09), CI = 0.17, 0.55), and greater depressive symptoms (β (SE) = 0.84 (0.07), CI = 0.70, 0.98). Characteristics associated with OSA were higher BMI (odds ratio [OR] = 1.13, CI = 1.06, 1.21), greater depressive symptoms (OR = 1.12, CI = 1.05, 1.20), and opioid use (OR = 0.51, CI = 0.26, 0.99).

Conclusions

Insomnia and OSA symptoms were very common in Veterans with OA, and a substantial proportion of individuals with symptoms may have been undiagnosed. Characteristics associated with insomnia and OSA symptoms were consistent with prior studies.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is increasing recognition that sleep disturbance is a common comorbidity among individuals with osteoarthritis (OA) [1,2,3,4]. Previous studies suggest that at least half of patients with OA report significant sleep disturbance [4,5,6], with some studies indicating the prevalence may be as high as 70% [1, 7]. Common sleep disturbances include insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Insomnia is marked by difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking too early, and these difficulties may contribute to daytime impairment. OSA is characterized by brief cessations in breathing which cause sleep to be fragmented and non-restorative. Sleep problems can have a negative impact on many outcomes, including psychological health, quality of life, and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [8, 9]. Among patients with OA, sleep problems are also associated with greater pain severity [4]. This relationship is likely a reciprocal one; in some studies sleep disturbance has predicted subsequent increases in pain severity, and in others, pain has predicted subsequent sleep disturbance [10].

Few studies have examined factors associated with sleep problems among patients with OA [1, 6]. Prior findings suggest that in addition to greater pain severity, other factors associated with worse sleep quality include: a greater number of arthritic joints, depression, poor overall health, reduced physical function, less social support, and less education [1, 6]. These studies evaluated overall sleep quality, but interestingly, there has been very little study of the prevalence of OSA or factors associated with OSA among patients with OA. The prevalence of OSA is elevated in patients with other rheumatic conditions [11], and because many patients with OA are overweight or obese – a main risk factor for OSA – it seems likely that rates would be elevated among these patients as well. In one study of 254 patients awaiting hip or knee arthroplasty, 6.7% of patients had OSA based on polysomnography (overnight sleep study). Importantly, the majority of these cases were undiagnosed. A recent analysis of a population-based cohort of men did not find links between OSA and the presence of musculoskeletal joint pain or the number of painful joints, although OA diagnosis was not specifically assessed [12]. However, in a study of patients referred for polysomnography, there was a strong association between OSA severity and OA severity, independent of body mass index [13]. The primary objective of this study was to examine the prevalence of OSA and insomnia symptoms among individuals with hip and knee OA. Secondary objectives were to: 1) examine participant characteristics associated with OSA and insomnia symptoms, 2) assess proportions of individuals with OSA and insomnia symptoms who may have been undiagnosed (based on information in the electronic medical record), 3) examine participant characteristics associated with under-diagnosis.

Methods

Study design

Data for these cross-sectional analyses were from baseline assessments collected in the study of Patient and Provider Interventions for Managing Osteoarthritis in Primary Care (PRIMO). Details of this study are described elsewhere [14, 15]. Briefly, this was a cluster-randomized controlled trial, with primary care providers (PCPs) assigned to two study arms: OA Intervention and Usual Care control. The institutional review board of the Department of Veterans Affairs HealthCare System in Durham, NC (DVAHCS) approved this study. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

Participants (N = 300) were patients at Durham VA Medical Center who had symptomatic hip OA (based on radiographic evidence in the electronic medical record) and/or symptomatic knee OA (based on radiographic evidence in the electronic medical record or meeting American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria) [16]. Participants were also overweight or obese (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25) and not currently meeting weekly physical activity guidelines set forth by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) [17]. Additional information regarding exclusion criteria and recruitment processes are provided elsewhere [14].

Measures

Insomnia

Insomnia symptoms were measured with the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). The scale content corresponds to DSM-IV criteria for insomnia and measures respondents’ perceptions of symptoms during the past 2 weeks. Scores were analyzed on a continuous scale with higher scores indicating greater insomnia symptom severity. In addition, a dichotomous indicator of symptoms consistent with insomnia was calculated, based on a score greater than 10 on the 0–28 scale [18].

Sleep apnea

OSA risk was assessed using the Berlin Questionnaire (BQ) [19], an11-item measure based on frequency and intensity of snoring, frequency of daytime sleepiness or fatigue, and presence of obesity or hypertension. Respondents are considered “high risk” for OSA if they have both persistent snoring and daytime fatigue in combination with a diagnosis of hypertension or elevated BMI (≥30 kg/m2) [20]. The sensitivity ranges from 76 to 84% and the specificity ranges from 38 to 59% among individuals in the general population. Among primary care patients, the sensitivity ranges from 54 to 86% and the specificity ranges from 43 to 87% [19].

Insomnia and OSA diagnoses

VA electronic medical records were reviewed to ascertain if a diagnosis of insomnia and/or OSA had ever been recorded for each participant. ICD-9 codes for insomnia were 780.52, 307.42, 327.02, 327.01, 307.41, 327.09, 46.72, 327, 292.85, 291.82, 780.51 and for sleep apnea were 786.03, 327.23, 780.53, 70.57, 327.21, 327.29, 327.2, 327.27, 780.51.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

We identified demographic and clinical characteristics with potential links to sleep disturbance based on prior studies [1, 6]. We collected self-reported information on age, sex, race/ethnicity (white vs. nonwhite), self-rated health (excellent, very good, or good vs. fair or poor), and number of joints with OA. Body mass index was calculated using measured height and weight collected at the baseline assessment.

Pain was measured using the 5-item subscale from the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), a self-reported measure of lower extremity pain in the previous 2 weeks [21,22,23]. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “none” to “extreme”; scores range from 0 to 25, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), a reliable and valid measure [24]. Participants rated the extent to which they were bothered by a series of complaints based on the DSM-5 criteria for Major Depressive Disorder over the prior 2 weeks. Each of the 8 questions is scored as 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), so that total scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptom severity. PTSD diagnosis was ascertained using a data pull to identify patients having ever received a PTSD diagnosis based on ICD-9 coding (code 309.81) in the electronic medical record. Opioid use was assessed because of its potential contributions to sleep problems. Participants were asked to bring all of their current pain-related medications to the baseline visit; the research assistant documented the class of each medication, and a dichotomous variable was created to indicate whether participants were using opioids at the time of study entry.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables, were calculated. Bivariate linear (insomnia scores on ISI) and logistic (dichotomous OSA risk from BQ) regression models were fit separately for each patient characteristic variable described above. We then fit multivariable linear (ISI) and logistic (BQ) regression models including all patient characteristic variables to examine the associations of patient and clinical characteristics with each condition. In the subgroup of participants that met self-reported criteria for insomnia or OSA, multivariable logistic regression models were fit to examine the association of each patient characteristic with the presence of ICD-9 codes for OSA or insomnia in the VA medical record. Residual plots from models were examined to assess normality assumptions, and goodness of fit was examined for logistic regression models. Linearity assumptions for the continuous covariates in all models were assessed and found not to have been violated. Data management and analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Participants were an average age of 61.1 (SD = 9.2) years, predominantly male (90.7%), and obese (mean BMI 33.8; SD = 5.8). Additional participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

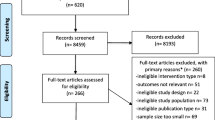

Descriptive characteristics of insomnia and OSA

Frequencies and descriptive characteristics for the ISI and BQ and medical record diagnosis codes are presented in Fig. 1. Seventy-six percent of participants (n = 228/300) screened positive for at least one sleep disturbance, including 23% screening “high risk” for sleep apnea alone (n = 70), and 10% screening positive for insomnia alone (n = 30). Forty-two percent (n = 128) screened positive for both insomnia and OSA. More than half of the sample (53%; n = 158/300) screened positive for insomnia, but only 22% (n = 35) of those individuals had an ICD-9 code for insomnia in the medical record. Although more than 66% of the sample (n = 198/300) screened in the “high risk” category for OSA, only about half of these (51%; n = 101) had an ICD-9 code for OSA in the medical record.

Demographic and clinical factors associated with insomnia severity

In bivariate models, higher self-reported insomnia severity was related to younger age, non-white race, poorer self-rated health, a diagnosis of PTSD in the medical record, higher self-reported arthritis pain, more self-reported depressive symptoms, more joints with arthritis, and current opioid use (Table 2). In the multivariable linear model, younger age (Estimate = − 0.09, SE = 0.04, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = − 0.16, − 0.02, p = .01), PTSD diagnosis (Estimate = 1.68, SE = 0.73, CI = 0.25, 3.11, p = .02), pain (Estimate = 0.36, SE = 0.10, CI = 0.17, 0.55, p < .001), and depressive symptoms (Estimate = 0.84, SE = 0.07, CI = 0.70, 0.98, p < .001), were associated with insomnia severity (Table 2).

Demographic and clinical factors associated with OSA risk

In bivariate logistic models, the odds of high risk of OSA were higher for younger age, fair or poor self-rated health, higher BMI, diagnosed with PTSD, higher self-reported arthritis pain, higher reporting of depressive symptoms, and reporting more joints with arthritis (Table 3). In the multivariable logistic model, BMI (Odds ratio (OR) = 1.1, CI = 1.06, 1.21, p < .001), depressive symptoms (OR = 1.12, CI = 1.05, 1.20, p = .002), and opioid use (OR = 0.51, CI = 0.26, 0.99, p = .05) were associated with high risk for OSA (Table 3).

Demographic and clinical factors associated with documented insomnia and OSA diagnoses

Among participants (n = 158) with a positive screen for insomnia, none of the patient characteristics examined in bivariate analyses (ORs < 1.48; p’s > .10) or the multivariable model (ORs < 1.47; p’s > .10) were associated with the presence of a diagnosis code in the medical record.

Among participants (N = 198) with a positive screen for OSA, in bivariate logistic models the following factors were associated with an OSA ICD-9 code in the medical record: poorer self-rated health (OR = 0.46, CI = 0.26, 0.80, p = .007), higher BMI (OR = 1.08, CI = 1.03, 1.14, p = .002), a diagnosis of PTSD (OR = 2.83, CI =1.53, 5.24, p = .001), more arthritis-related pain (OR = 1.08, CI = 1.00, 1.16, p = .05), more symptoms of depression (OR = 1.10, CI = 1.04, 1.16, p < .001), and opioid use (OR = 2.09, CI = 1.12, 3.90, p = .02). In multivariable models, among participants with a positive screen for OSA (BQ “high risk”), the odds of having with a diagnosis code in the medical record was greater for higher BMI (OR = 1.11, CI = 1.04,1.18, p < .001), a diagnosis of PTSD in the medical record (OR = 2.51, CI = 1.24, 5.07, p = .01), and more self-reported depressive symptoms (OR = 1.08, CI = 1.00, 1.16, p = .04).

Discussion

Self-reported symptoms consistent with insomnia and OSA were highly prevalent in this cohort, with a high degree of overlap between those screening positive for both conditions. Patient characteristics associated with insomnia and OSA were largely consistent with prior studies. A key finding was that many individuals with insomnia and OSA symptoms did not have corresponding diagnosis codes in the medical record, potentially indicating substantial under-diagnosis. This illustrates the need for more consistent screening for insomnia and OSA, given numerous negative consequences of untreated sleep problems [8, 9].

Fifty-two percent of this sample screened positive for insomnia, which is notably higher than the estimated prevalence of insomnia in the general population, (18%) and in adults aged 55–64 (24%) [25]. This finding is consistent with higher reported prevalence of insomnia in Veterans in other studies, with estimates ranging from 24 to 54% [26]. Although a higher prevalence of insomnia has also been reported in individuals with OA (23%) compared to the general population [2], the prevalence in this sample was still much higher. Overall, our results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating links of insomnia with PTSD diagnosis, pain, and depressive symptoms in the general population [2, 27], among individuals with OA (all but PTSD) [1], and in Veterans [26, 28]. Our finding that increased age was associated with a lower likelihood of screening positive for insomnia is consistent with prior research among Veterans [28, 29], though the converse association has been shown in multiple studies of the general population [30, 31].

The 66% prevalence of “high risk” for OSA is much greater than the estimated prevalence of 17% among US men aged 50–70 (which is a similar demographic to our study sample). Veterans and individuals with OA tend to exhibit characteristics associated with higher OSA risk, including older age, higher BMI, and higher rates of medical comorbidity. The majority of Veterans are also male, and many have psychiatric comorbidities, which are additional OSA risk factors [32, 33] Study findings were consistent with past work showing associations of OSA with BMI and depression, including analyses in Veterans and patients referred for total joint arthroplasty [34,35,36]. BMI-related findings underscore the importance of OSA-targeted questioning when assessing sleep concerns, as multiple analyses have failed to find associations between BMI and general assessments of sleep quality in individuals with OA [1, 5]. An association between OSA and opioid use is also consistent with prior literature [37].

Forty-three percent of our sample screened positive for both insomnia and OSA. A high prevalence (39–58%) of insomnia symptoms have been reported in individuals in the general population with OSA, and between 29 and 67% of individuals with insomnia had symptoms consistent with high OSA risk [38]. High rates of comorbid insomnia and OSA have also been noted in military personnel [39] and Veterans [40], particularly in those with PTSD, who often present with both conditions due to increased sympathetic activation [41, 42]. Symptoms shared by both insomnia and OSA, including fragmented sleep and daytime impairment, may have contributed to the significant degree of screening overlap and thus, the true comorbidity in this sample may be overestimated.

Consistent with the literature for both conditions, our results suggest a significant gap between the presence of insomnia and OSA symptoms and documented diagnoses [43]. Sleep concerns may be minimized or overlooked in primary care visits, particularly when greater attention is devoted to other chronic conditions.. Among Veterans at high risk for OSA in this study, those with, PTSD, higher BMI, and greater depressive symptoms were more likely to have an OSA diagnosis noted in the medical record. This higher rate of documentation in the medical record could be due to more severe sleep disturbance among individuals with these health conditions or because physicians were more likely to screen for or recognize sleep disturbance among individuals with these risk factors [36].

There are some limitations to this study. First, the BQ is not validated for diagnostic use, has a large range of specificity, and may overestimate prevalence in an overweight population. Second, the use of ICD-9 codes may have under-estimated actual physician diagnoses of insomnia and OSA, which may have been documented elsewhere in the medical record. Third, we did not collect patient information about prior treatment for sleep problems (e.g., CPAP), which may have influenced screening scale responses. Fourth, we did not collect information on self-reported PTSD symptoms and therefore relied on the presence of a diagnosis in the medical record, which may not always be an accurate reflection of symptoms. Fifth, we did not obtain de novo radiographs and therefore did not have a measure of radiographic OA severity. Finally, the study population consisted of Veterans (primarily male), with BMIs ≥25, thus, these findings may not generalize across different populations. In particular, this was a group with higher risk for sleep problems than the general population, and patterns of diagnosis may differ outside of the VA healthcare system.

Conclusions

In summary, this study found high rates of insomnia and OSA among Veterans with OA. It is one of the first studies to examine the prevalence of OSA among patients with OA and illustrates the importance of screening for OSA in this patient population. Results also indicated that unrecognized insomnia and OSA may be common. Given the potential for sleep problems to exacerbate disease processes, pain, and disability, and increase risks for other health problems, screening and providing evidence-based treatment for both insomnia and OSA should be a priority for providers working with individuals with OA.

References

Hawker G, French M, Waugh E, Gignac M, Cheung C, Murray B. The multidimensionality of sleep quality and its relationship to fatigue in older adults with painful osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(11):1365–71.

Louie GH, Tektonidou MG, Caban-Martinez AJ, Ward MM. Sleep disturbances in adults with arthritis: prevalence, mediators, and subgroups at greatest risk. Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(2):247–60.

Smith MT, Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Robinson M, Haque U, Quain A, McInrue E, Han D, Leoutsakis J, Haythornthwaite JA. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for insomnia in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, active placebo–controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(5):1221–33.

Smith MT, Quartana PJ, Okonkwo RM, Nasir A. Mechanisms by which sleep disturbance contributes to osteoarthritis pain: a conceptual model. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(6):447–54.

Allen KD, Renner JB, Devellis B, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Osteoarthritis and sleep: the Johnston County osteoarthritis project. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(6):1102–7.

Wilcox S, Brenes GA, Levine D, Sevick MA, Shumaker SA, Craven T. Factors related to sleep disturbance in older adults experiencing knee pain or knee pain with radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(10):1241–51.

Taylor-Gjevre RM, Gjevre JA, Nair B, Skomro R, Lim HJ. Components of sleep quality and sleep fragmentation in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2011; Epub ahead of print

Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Riedel BW, Bush AJ. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep. 2007;30(2):213–8.

Force USPST. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea in adults: us preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317(4):407–14.

Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539–52.

Taylor-Gjevre RM, Nair BV, Gjevre JA. Obstructive sleep apnoea in relation to rheumatic disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;52(1):15–21.

Li JJ, Appleton SL, Gill TK, Vakulin A, Wittert GA, Antic NA, Taylor AW, Adams RJ, Hill CL. Association of Musculoskeletal Joint Pain with Obstructive Sleep Apnea, daytime sleepiness, and poor sleep quality in men. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(5):742–7.

Kanbay A, Kokturk O, Pihtili A, Ceylan E, Tulu S, Madenci E, Koseoglu H, Verbraecken J. Obstructive sleep apnea is a risk factor for osteoarthritis. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:PA340.

Allen KD, Bosworth HB, Brock DS, Chapman JG, Chatterjee R, Coffman CJ, Datta SK, Dolor RJ, Jeffreys AS, Patient JKA. Provider interventions for managing osteoarthritis in primary care: protocols for two randomized controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1):60.

Allen KD, Yancy WS, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ, Jeffreys AS, Datta SK, McDuffie J, Strauss JL, Oddone EZ. A combined patient and provider intervention for Management of Osteoarthritis in veterans: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(2):73–83.

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke T, Greenwald R, Hochberg M. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–49.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical activity guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC; 2008.

Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601–8.

Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(7):485–91.

Chiu H-Y, Chen P-Y, Chuang L-P, Chen N-H, Tu Y-K, Hsieh Y-J, Wang Y-C, Guilleminault C. Diagnostic accuracy of the berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: a bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2016

Bellamy N. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically-important patient-relevant outcomes following total hip or knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. J Orthop Rheumatol. 1988;1:95–108.

Bellamy N. WOMAC: A 20-year experimental review of a patient-centered self-reported health status questionnaire. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2473–6.

Bellamy N, Buchanan W. A preliminary evaluation of the dimensionality and clinical importance of pain and disability in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Clin Rheumatol. 1986;5(2):231–41.

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1):163–73.

Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, Croft JB. Trends in insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness among U.S. adults from 2002 to 2012. Sleep Med. 2015;16(3):372–8.

Jenkins MM, Colvonen PJ, Norman SB, Afari N, Allard CB, Drummond SP. Prevalence and mental health correlates of insomnia in first-encounter veterans with and without military sexual trauma. Sleep. 2015;38(10):1547.

Tang NK, McBeth J, Jordan KP, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Croft P, Wilkie R. Impact of musculoskeletal pain on insomnia onset: a prospective cohort study. Rheumatology. 2015;54(2):248–56.

Hermes E, Rosenheck R. Prevalence, pharmacotherapy and clinical correlates of diagnosed insomnia among veterans health administration service users nationally. Sleep Med. 2014;15(5):508–14.

Hughes JM, Martin JL. Sleep characteristics of veterans affairs adult day health care participants. Behav Sleep Med. 2015;13(3):197–207.

Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(2):97–111.

Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Coulouvrat C, Fitzgerald T, Hajak G, Roth T, Shahly V, Shillington AC, Stephenson JJ, Walsh JK. Insomnia, comorbidity, and risk of injury among insured Americans: results from the America insomnia survey. Sleep. 2012;35(6):825–34.

Sharafkhaneh A, Giray N, Richardson P, Young T, Hirshkowitz M. Association of psychiatric disorders and sleep apnea in a large cohort. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1405.

Colvonen PJ, Masino T, Drummond SP, Myers US, Angkaw AC, Norman SB. Obstructive sleep apnea and posttraumatic stress disorder among OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(5):513.

Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):136–43.

Babson KA, Del Re A, Bonn-Miller MO, Woodward SH. The comorbidity of sleep apnea and mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders among obese military veterans within the veterans health administration. J Clin Sleep Med 2013; 9(12):1253–1258.

Kapur V, Strohl KP, Redline S, Iber C, O'connor G, Nieto J. Underdiagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome in US communities. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(02):049–54.

Walker JM, Farney RJ, Rhondeau SM, Boyle KM, Valentine K, Clowrad TV, Shilling KC. Chronic opioid use is a risk factor for the development of central sleep apnea and ataxic breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5):455–61.

Luyster FS, Buysse DJ, Strollo PJ Jr. Comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea: challenges for clinical practice and research. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6(2):196–204.

Mysliwiec V, Matsangas P, Baxter T, McGraw L, Bothwell NE, Roth BJ. Comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea in military personnel: correlation with polysomnographic variables. Mil Med. 2014;179(3):294–300.

Mustafa M, Erokwu N, Ebose I, Strohl K. Sleep problems and the risk for sleep disorders in an outpatient veteran population. Sleep Breath. 2005;9(2):57–63.

Gupta MA. Review of somatic symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(1):86–99.

Krakow B, Melendrez D, Warner TD, Dorin R, Harper R, Hollifield M. To breathe, perchance to sleep: sleep-disordered breathing and chronic insomnia among trauma survivors. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(04):189–202.

Redline S. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea: implications for the sleep health of the population. JAMA. 2017;317(4):368–70.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Ambulatory Care Service of the Durham VA Medical Center for participation in the study; study team members Jennifer Chapman, Karen Juntilla, and Laurie Marbrey; and all of the Veterans who participated in this study.

Funding

This project was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service (IIR 10–126). This work was also supported by the Center of Innovation for Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13–410) at the Durham Veterans Affairs HealthCare System. Dr. Taylor was funded by a VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Health Services Research and Development Service postdoctoral fellowship (TPH 21–000) while completing this work at the Durham Veterans Affairs HealthCare System. Dr. Hughes is currently funded by a VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Health Services Research and Development Service postdoctoral fellowship (TPH 21–000). Dr. Bosworth is funded by a Department of Veterans Affairs HSR&D Research Career Scientist award (08–027). Dr. Allen receives support from National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center P60 AR062760.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclaimer

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SST was the primary writer of the manuscript. JH was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. CC and AJ analyzed and interpreted the data. CU contributed to the analytic design and provided significant feedback on the manuscript. HB, EO, and WY contributed significantly to the original conception and design of the trial, helped to oversee the collection of data, and provided significant feedback on the manuscript. KA was the PI on the original trial and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board of the Department of Veterans Affairs HealthCare System in Durham, NC (DVAHCS) approved this study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, S.S., Hughes, J.M., Coffman, C.J. et al. Prevalence of and characteristics associated with insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea among veterans with knee and hip osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 19, 79 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-1993-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-1993-y