Abstract

Background

This study evaluated the effect of early anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on the subsequent risk of total knee replacement (TKR) surgery.

Methods

This retrospective observational study included a hospital-based cohort of 200 patients diagnosed with severe RA who received treatment with anti-TNF therapy between 2003 and 2014. Clinical parameters including age, sex, body mass index, and the time from the diagnosis of RA to the initiation of anti-TNF therapy were analyzed.

Results

Of the 200 enrolled patients, 84 underwent an early intervention (≤3 years from the diagnosis of RA to the initiation of anti-TNF therapy), and 116 underwent a late intervention(>3 years from the diagnosis of RA to the initiation of anti-TNF therapy). Five (6.0%) patients in the early intervention group underwent TKR compared to 31 (26.7%) in the late intervention group (p = 0.023). After adjusting for confounding factors, the late intervention group still had a significantly higher risk of TKR (p = 0.004; odds ratio, 5.572; 95% confidence interval, 1.933–16.062). Those receiving treatment including methotrexate had a lower risk of TKR (p = 0.004; odds ratio, 0.287; 95% confidence interval, 0.122–0.672).

Conclusions

Delayed initiation of anti-TNF therapy in the treatment of severe RA was associated with an increased risk of TKR surgery. Adding methotrexate treatment decreased the risk of future TKR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a major public health problem and one of the most common auto-immune diseases. Patients with RA typically experience significant disability, reduced life expectancy, and poor quality of life [1]. As RA progresses, patients develop deformities and stiffness of the joints, especially in the hands and feet, and this is the major cause of disability. Damage to the joints is progressive and irreversible. The knee is a major weight-bearing joint in which patients with severe RA may experience bone destruction and disability [2,3,4,5], and some will require total knee replacement (TKR). Therefore, patients with RA can have significant long-term consequences [6,7,8,9]. One 18-year longitudinal study published in 1998 estimated that 25% of all patients with RA required total joint replacement surgery [10]. However, the incidence of joint replacement surgery in patients with RA has decreased in recent years, primarily because of the development of more effective medical treatment [11,12,13]. In a Norwegian register-based study, Nystad and Fenstad reported a decrease in the incidence of orthopedic surgery in patients with RA that continued into the era of biologics. The general increasing trend in the use of synthetic and biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has thus reduced the incidence of joint destruction and improved the long-term prognosis of patients with RA [14].

Current anti-rheumatic therapies attempt to alleviate pain and either delay or prevent joint deterioration. Traditional DMARDs such as methotrexate can control disease activity and prevent joint destruction in patients with RA [15]. Da Silva et al. reported a trend of a reduction in the incidence of joint surgery in patients with RA since 1985, due to advances in medical management [16]. In addition, Widdifield et al. reported that a longer duration of exposure to DMARDs soon after a diagnosis of RA was associated with a longer time to joint replacement surgery. Early intensive treatment for RA has also been reported to reduce the need of joint replacement surgery [17]. These findings have important implications for the utilization of health care resources.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is known to play a major role in joint destruction in RA, and anti-TNF-α agents have been shown to slow the progression of joint destruction [18]. To date, however, there is little information regarding the effect of biological agents on the need for joint replacement surgery. Although Momohara and De Piano found a decrease in the incidence of joint replacement surgery after the use of biologics, Aaltonen and colleagues reported that the use of biological drugs did not reduce the need for joint replacement surgery in patients with similar on-medication disease activity [19].

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of a delayed initiation of anti-TNF therapy in patients diagnosed with severe RA on the subsequent risk of TKR surgery. The hypothesis was that the delayed use of biological anti-rheumatic drugs would increase the need for joint replacement surgery due to progressive tissue damage caused by RA.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and it was conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. All information was de-identified before data analysis, and thus informed consent was not required. Data of all patients with RA who received anti-TNF therapy between January 2003 and December 2014 were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were: 1) a diagnosis of RA based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria [20]; 2) severe RA (i.e., disease activity score > 5.1 based on the DAS28 criteria) before anti-TNF treatment for more than 6 months; and 3) taking at least two DMARDs for more than 2 years. The exclusion criteria were an age ≤ 20 years or >80 years and those who received TKR before the initiation of anti-TNF therapy.

Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), underlying diseases, use of concomitant DMARDs (i.e., hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, leflunomide, cyclosporine, sulfasalazine, azathioprine), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein level were recorded at baseline and throughout the study period. DAS28 was calculated before anti-TNF therapy and every 3 months thereafter. The patients who underwent TKR during the 12-year study period were identified and analyzed. The time from the diagnosis of RA to the initiation of anti-TNF therapy was also analyzed. Follow-up data for each participant were recorded from the time of the initiation of anti-TNF therapy to November 30, 2014.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 21.0 (SPSS; Chicago, IL, USA). Logistic regression analysis was used to study the associations between various factors and TKR, and the odds ratios (ORs) for TKR in the patients with RA prescribed with anti-TNF therapy (years) were calculated, with adjustments for possible confounding factors such as DAS28 and the use of methotrexate.

Results

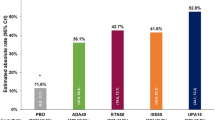

A total of 1258 patients with RA were identified during the study period, of whom 256 had severe RA. Fifty of the patients with severe RA did not received biological anti-TNF agents and 206 did, six of whom were excluded due to undergoing TKR prior to anti-TNF agent therapy. Overall 200 patients with severe RA received anti-TNF agents (etanercept, 104 [52.0%]; adalimumab, 92 [46.0%]; and 4 (2%) golimumab. Among them, 84 underwent an early intervention (≤3 years from the diagnosis of RA to the initiating anti-TNF therapy), and 116 underwent a late intervention (>3 years from the diagnosis of RA to the initiation of anti-TNF therapy) (Table 1). The mean age at the diagnosis of RA in the early intervention group was 48.99 ± 13.46 years, which was significantly older than in the late intervention group (p = 0.002). In the early intervention group, 5 (6.0%) patients underwent TKR, compared to 31 (26.7%) in the late intervention group (p = 0.023).

There were no differences in gender, BMI, underlying medical illnesses and oral disease modifying anti-rheumatic agents. After adjusting for confounding factors, the late intervention group still had a higher risk of TKR (p = 0.001; OR, 5.572; 95% CI, 1.933–16.062). Those receiving treatment including methotrexate also had a lower risk of TKR (p = 0.004; OR, 0.287; 95% CI, 0.122–0.672) (Table 2).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to identify factors that affected the need for knee replacement surgery in patients with RA. This results showed that use of methotrexate decreased the need for TKR in patients with RA, which is consistent with the findings of da Silva et al. who found that patients prescribed with synthetic DMARDs had better clinical outcomes (i.e., disease activity, functional capacity, radiographic score, and other clinical measures) than those who did not receiving synthetic DMARDs [16].

After adjusting for confounding factors, a longer duration from the diagnosis of RA to the initiation of anti-TNF therapy significantly increased the need for subsequent TKR. A possible reasons why the delayed use of anti-TNF therapy in patients with severe RA may increase the risk of TKR is that anti-TNF agents can reduce disease activity in patients with RA and either slow or completely halt the progression of joint erosion, even when there are persistent clinical signs of joint inflammation [21,22,23,24]. Further, anti-TNF agents have prolonged effects on the joints. In particular, a long-term, open-label trial on the safety and efficacy of DMARDs for the treatment of RA indicated that anti-TNF agents (but not other DMARDs) had sustained efficacy and favorable safety profiles even after 3 years of use [25].

There are several limitations to this study. This was a retrospective study with a relatively small sample size, and all data were collected from secondary sources (hospital medical records). As such, there may have been missing data, data collected by different observers, and disparity in the criteria used for different patients. A larger sample size is needed to confirm the finding that the early initiation of anti-TNF therapy can reduce the risk of TKR. In addition, a prospective study would not have the weaknesses inherent in a retrospective study. However, all available data were used in this single center cohort, which means the study design and sample size were the best available to us. In addition, a limitation of the retrospective nature of the study is that radiographs of the knees before anti-TNF treatment were not available, so the key to delaying TKR was dependent on the status of the knee at the time of presentation. In addition, the ability to control the disease with drug therapy will be limited.

Conclusions

It is generally accepted that patients with severe RA should seek medical attention and treatment as soon as possible. Our results suggest that when patients with RA delay the initiation of anti-TNF therapy, they have an increased risk of subsequent TKR. Further investigations on this topic are warranted to provide further important information that may help guide decisions with regards resource allocation for patients with RA.

Abbreviations

- Anti-CCP:

-

Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DAS28:

-

Disease activity score in 28 joints

- DMARDs:

-

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- SE:

-

Standard error

- TKR:

-

Total knee replacement

- TNF:

-

Anti-tumor necrosis factor

References

Harris ED Jr. Rheumatoid arthritis. Pathophysiology and implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(18):1277–89.

Kraan MC, Reece RJ, Smeets TJ, Veale DJ, Emery P, Tak PP. Comparison of synovial tissues from the knee joints and the small joints of rheumatoid arthritis patients: Implications for pathogenesis and evaluation of treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(8):2034–8.

Mundinger A, Ioannidou M, Meske S, Dinkel E, Beck A, Sigmund G. MRI of knee arthritis in rheumatoid arthritis and spondylarthropathies. Rheumatol Int. 1991;11(4–5):183–6.

Yamato M, Tamai K, Yamaguchi T, Ohno W. MRI of the knee in rheumatoid arthritis: Gd-DTPA perfusion dynamics. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17(5):781–5.

Poleksic L, Musikic P, Zdravkovic D, Watt I, Bacic G. MRI evaluation of the knee in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(Suppl 3):36–9.

Wilson FC. Total replacement of the knee in rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective study of the results of treatment with the Walldius prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(7):1429–43.

Wilson FC. Total replacement of the knee in rheumatoid arthritis. Part II. A prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;94:58–64.

Chand K. The knee joint in rheumatoid arthritis. III. Treatment by hinged total knee prosthetic replacement. Int Surg. 1974;59(11–12):600–7.

Chand K. The knee joint in rheumatoid arthritis. IV. Treatment by nonhinged total knee prosthetic replacement. Int Surg. 1975;60(1):11–8.

Wolfe F, Hawley DJ. The longterm outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis: Work disability: a prospective 18 year study of 823 patients. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(11):2108–17.

Jamsen E, Virta LJ, Hakala M, Kauppi MJ, Malmivaara A, Lehto MU. The decline in joint replacement surgery in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a concomitant increase in the intensity of anti-rheumatic therapy: a nationwide register-based study from 1995 through 2010. Acta Orthop. 2013;84(4):331–7.

Momohara S, Inoue E, Ikari K, Kawamura K, Tsukahara S, Iwamoto T, Hara M, Taniguchi A, Yamanaka H. Decrease in orthopaedic operations, including total joint replacements, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis between 2001 and 2007: data from Japanese outpatients in a single institute-based large observational cohort (IORRA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):312–3.

De Piano LP, Golmia RP, Scheinberg MA. Decreased need of large joint replacement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a specialized Brazilian center. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(4):549–50.

Nystad TW, Fenstad AM, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen AK, Fevang BT: Reduction in orthopaedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a Norwegian register-based study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015:1–7.

Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, Ishiguro N, Ryu J, Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, Yamanaka H, Fujii K, Yoshinaga T, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Modern rheumatology / the Japan Rheumatism Association. 2011;21(4):343–51.

da Silva E, Doran MF, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM, Matteson EL. Declining use of orthopedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Results of a long-term, population-based assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(2):216–20.

Widdifield J, Moura CS, Wang Y, Abrahamowicz M, Paterson JM, Huang A, Beauchamp ME, Boire G, Fortin PR, Bessette L, et al. The Longterm Effect of Early Intensive Treatment of Seniors with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Comparison of 2 Population-based Cohort Studies on Time to Joint Replacement Surgery. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(5):861–8.

Tada M, Koike T, Okano T, Sugioka Y, Wakitani S, Fukushima K, Sakawa A, Uehara K, Inui K, Nakamura H. Comparison of joint destruction between standard- and low-dose etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis from the Prevention of Cartilage Destruction by Etanercept (PRECEPT) study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(12):2164–9.

Aaltonen KJ, Virkki LM, Jamsen E, Sokka T, Konttinen YT, Peltomaa R, Tuompo R, Yli-Kerttula T, Kortelainen S, Ahokas-Tuohinto P, et al. Do biologic drugs affect the need for and outcome of joint replacements in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? A register-based study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(1):55–62.

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–24.

Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, Tindall EA, Fleischmann RM, Bulpitt KJ, Weaver AL, Keystone EC, Furst DE, Mease PJ, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):478–86.

Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, Genovese MC, Wasko MC, Moreland LW, Weaver AL, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1586–93.

Dohn UM, Skjodt H, Hetland ML, Vestergaard A, Moller JM, Knudsen LS, Ejbjerg BJ, Thomsen HS, Ostergaard M. No erosive progression revealed by MRI in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with etanercept, even in patients with persistent MRI and clinical signs of joint inflammation. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(11):1857–61.

van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Rodriguez-Valverde V, Codreanu C, Bolosiu H, Melo-Gomes J, Tornero-Molina J, Wajdula J, Pedersen R, Fatenejad S. Comparison of etanercept and methotrexate, alone and combined, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: two-year clinical and radiographic results from the TEMPO study, a double-blind, randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(4):1063–74.

Klareskog L, Gaubitz M, Rodriguez-Valverde V, Malaise M, Dougados M, Wajdula J. A long-term, open-label trial of the safety and efficacy of etanercept (Enbrel) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis not treated with other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(12):1578–84.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for providing the related data.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YCC had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. WCC was responsible for the study design. WCC, TTC, HML, SFY, JFC, BYJS, CYH, and CHK performed data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and final approval of the manuscript. The manuscript was prepared by WCC. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and was conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. According to local government policy, no additional informed consent was required, and all information was de-identified before data analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, YC., Chiu, WC., Cheng, TT. et al. Delayed anti-TNF therapy increases the risk of total knee replacement in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18, 326 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1685-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1685-z