Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is remarkably frequent in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Albuminuria is a marker of vascular endothelial dysfunction and predictor of CVD events. Albuminuria is prevalent in patients with COPD as it has been shown in Caucasian and Oriental populations with COPD. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of Albuminuria and COPD severity correlates among black patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in order to see whether a similar trend of albuminuria is also prevalent in this population.

Methods

A total of 104 COPD patients were enrolled in the study. Lung functions were assessed by means of the Easy One™ spirometer. Albuminuria defined by urine albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) was tested using CYBOW 12MAC microalbumin strips in a random spot urine collection. SPSS version 20 was used for data analysis.

Results

In the studied population, 25/104 (24%) patients had albuminuria and 16/104 (15.4%) patients had CVD. Abnormal urine albumin (Albuminuria and Proteinuria) was present in all patients with CVD. In the subset of 46 COPD patients assessed for severity, 60.9% (95%CIs 46.1–73.9) had moderate COPD and 30.4% (95% CIs, 17.9–49.0) severe COPD. Albuminuria was moderately significantly associated with COPD severity, p = 0.049; (0.049 < p < 0.05). Participants who ever smoked cigarettes had significantly likelihood of severe and very severe COPD (OR 11.5; 95% CIs, 1.3, 98.4) however, the significance was lost when adjusted for age and gender.

Conclusion

Albuminuria was prevalent in patients with COPD and it had a significant association with COPD severity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is currently the 4th cause of death worldwide; projected the 3rd by 2020 [1]. COPD has potential extra-pulmonary effects but it can be prevented and treated, however, no cure has been established. Cardiovascular disease is the most common extra-pulmonary presentation of COPD and therefore patients are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to acute cardiovascular events [2].

Different studies have shown that cardiovascular disease is common in COPD and likely to add to the complexity of the disease [3]. For instance; in the USA, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease in COPD patients was reported to be 22% versus 9% in non-COPD patients. In the UK, the relative risks of angina and myocardial infarction were 1.67 and 1.75, respectively, versus subjects without COPD [4]. A CONSISTE study in Spain showed that patients with COPD had a significantly higher prevalence of ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease compared non-COPD group [5].

Albuminuria is known to be a sensitive biomarker of endovascular dysfunction and a significant predictor of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in the general population. Vascular endothelial dysfunction is evident in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [6]. Presence of albuminuria indicates a state of generalized endothelial dysfunction and therefore it is a screening tool for early cardiovascular disease prevention [2]. Albuminuria is common in COPD patients and it independently correlates significantly with hypoxemia [2, 6, 7]. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of albuminuria and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity correlates in patients with COPD of African cohort. The results from this study will provide an insight on the prevalence of albuminuria in black population with COPD.

Methods

Study design and setting

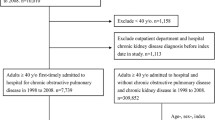

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study. It was carried out in outpatient pulmonology clinic at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania from July 2016 to December 2016. Study participants were consecutively recruited from the Muhimbili national hospital pulmonology clinic. Patients with clinical diagnosis of COPD made by the attending physician/pulmonologist, underwent spirometry examination to confirm COPD diagnosis. A total of 117 patients were assessed for the study eligibility; of these, 58 were known COPD on follow up the clinic and 59 were new clinically diagnosed COPD patients. All known COPD patients underwent repeated spirometry without bronchodilator to re-confirm COPD diagnosis, of which all 58 were re-confirmed. The new clinically diagnosed COPD patients underwent both pre and post-bronchodilator to confirm COPD diagnosis, of which 46 were confirmed COPD diagnosis. Hence a total of 104 confirmed COPD cases were enrolled for the study (see Fig. 1). Inclusion criteria were (1) Patients with confirmed COPD defined FEV1/FVC < 70% of post-bronchodilator and pre-bronchodilator spirometry for new and previous cases respectively and (2) Age 18 years and above. Exclusion criteria were patients with urinary tract infection (UTI). The study was approved by the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences Senate Research and Publication Committee. The written consent was given by study participants.

A structured questionnaire was used to collect all important information from the study participants. These included a history of symptoms suggestive of COPD; progressive dyspnoea, chronic cough and chronic sputum production and history of cigarette smoking and biomass fuel exposure. Also, a history of any known associated co-morbidities like renal, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and malignancy condition were obtained. Baseline clinical parameters; blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and anthropometrics; body weight, height, and BMI were measured.

Assessment of lung functions

Lung functions were assessed by means of the Easy One™ spirometer available at the clinic, manufactured by ndd Medizintechnik-Switzerland which complies with the 2005 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) spirometry standards and does not need daily calibration [8,9,10]. Spirometry was performed without a nose clip. Disposable mouthpieces (spirettes) were used and discarded after single use. COPD was classified as per 2015 GOLD guidelines.

Assessment of albuminuria

The urinary albumin was screened using CYBOW 12MAC microalbumin strips in a random spot urine collection. These strips were available in a local market, manufactured by DFI CO., Ltd. 542–1 Daman Ri, Jinrye-Myun Gimhae-City Gyung-Nam Korea and have been approved by Food and Drug Authority (FDA). The reagent strip is a multi-strip for rapid determination of 12 components including protein, microalbumin, creatinine, nitrite, and leucocytes. CYBOW 12MAC reagent strips are both qualitative and semi-quantitative dip strips [11]. The earlier product of the strips (CYBOW 2MAC) has been used in some studies to assess for urinary albumin [12]. The sensitivity of this test ranged from 10 mg/L to150mg/L for microalbumin and 0.9 to 26.5 mmol/L for urine creatinine. Albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) was then calculated to determine the level of albuminuria and expressed as mg/mmol. ACR < 2 mg/mmol for male and < 2.8 mg/mmol for female defined normoalbuminuria, ACR ≥ 2.5–29.9 mg/mmol for male and ≥ 3.5–29.9 mg/mmol for female defined albuminuria and ACR ≥ 30 mg/mmol for both male and female defined macroalbuminuria/proteinuria.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were entered into EpiData 3.1 sheet and cleaned. Chi-square test and logistic regression were employed to ascertain the measure of statistical association by using SPSS version 20. The results were expressed as absolute numbers, mean plus or minus standard deviation (SD), and percentages. A p-value of < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 104 study participants were analysed. The mean age was 58.6 ± 14.2 (SD) years, males constituted 56.7% of the study population. More than one-third of the study participants were of age range 42–83 years. More than half 56(53.8%) of study participants were smokers. Among smokers a large proportion 60.7% were heavy smokers; smoked > 10 pack year. A significant number of participants had a history of exposure to biomass fuel (firewood) and kerosene as cooking fuels; 40(38.5%) and 63 (60.6%) respectively, (Table 1).

A chronic cough and progressive dyspnoea were the most mentioned COPD related symptoms; 102/104 (98.1%) and 46/104 (44.2%) respectively. A small proportion 16/104 (15.4%) of the study participants had comorbid CVD by history. About one-third of the participants were overweight 32/104 (30.8%), and 12/104 (11.5%) obese. The proportion of study participants with elevated blood pressure on single reading was 39/104 (37.5%). (Table 2).

COPD severity

Of the 46 COPD patients assessed for COPD severity; 60.9% (95%CIs 46.1–73.9) had moderate COPD and 30.4% (95%CIs, 17.9–49.0) severe COPD (Table 3).

Predictors of COPD severity

In unadjusted regression model participants who ever smoked cigarette was significantly likely to have severe and very severe COPD (OR 11.5; 95% CI 1.3, 98.4; p < 0.05), however, the significance was lost when adjusted for age and gender. The participants who were; currently smokers, heavy smokers, and with a history of CVD had a non-significant increased the likelihood of severe and very severe COPD. (Table 4).

Albuminuria

All 104 study participants underwent a dipstick urinalysis test using CYBOW 12MAC strips. Out of 104 participants 31 (29.8%) had proteinuria, 25 (24.0%) albuminuria, and 48(46.2%) normoalbuminuria. No urine sample had features of urinary tract infections. Therefore, the prevalence of albuminuria was 24%. Abnormal urine albumin (albuminuria and proteinuria) was prevalent in all study participants with CVD (Table 5).

COPD severity and albuminuria

Of the 46 participants assessed for COPD severity, albuminuria moderately significantly associated with COPD severity or with the lower level of FEV1% predicted, p = 0.049; (0.049 < p < 0.05). (Table 6).

Discussion

This was a hospital-based cross-section study of 104 black Africans patients with COPD determining the prevalence of albuminuria and COPD severity correlates. Regarding COPD severity in the current study, a large proportion of study participants had moderate to severe COPD according to GOLD classification; 60.9% (95% [CI], 17.9–49.0] and 30.4, 95% [CI], 46.1–73.9) respectively. In a study by Mehmood K et al. the COPD was also classified according to GOLD criteria and the majority of study participants were in stage III (severe) and above; 55.7% [2]. This discrepancy can be accounted for by differences in study design and characteristics of study population between the two studies in respect to cigarette smoking. In the current study, the proportion of cigarette smoking was 53.8% while in the study by Mehmood K et al. all study participants were heavy smokers of >10pack year.

Albuminuria prevalence in the current study was 24% (95% [CI], 17.0–33.0) while abnormal urine albumin (albuminuria and proteinuria) was prevalent in all study participants with CVD. The presence of CVD was assessed through history alone. Of 104 study participants, 16/104 (15.5%) had CVD, of which 12 participants had the coronary arterial disease, 3 resolved stroke, and 1 hypertensive heart disease. More extra-pulmonary comorbidities could have been detected if laboratory markers were to be used, which was not the case in the current study. In a prospective cohort study conducted in India by Mehmood K et al. on albuminuria and hypoxemia in patients with COPD in 97 COPD smokers versus 94 non-COPD smokers as a controls over a period of 2 years; albuminuria was found to be more frequent in COPD smokers compared to smokers without COPD (20.6%versus 7.4% p = 0.007). The confounding co-morbidities like renal disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease were excluded using laboratory biomarkers and relevant history [2]. In the current study comorbid CVD, renal and diabetes were excluded by history only and hence might explain the differences in albuminuria prevalence.

The prevalence of albuminuria in the current study was similar to the prevalence of albuminuria found in a study done in Spain by Ciro Casanova et al. on albuminuria and hypoxemia in COPD patients (129 COPD cases versus 51 controls). In that study, the prevalence of albuminuria was 24% in patients with COPD and smoking history versus 6% in non-COPD smokers control; (p = 0.005), and all confounding co-morbidities were excluded using history and laboratory biomarkers [13].

In the current study, the COPD severity and albuminuria were significantly inversely related; the risk of albuminuria increased moderately significantly with COPD severity or the lower level of FEV1% predicted, (p = 0.049). All COPD patients with normoalbuminuria had GOLD stage I (mild) and II (moderate). A 12-year follow-up study in Norway by Solfrid Romundstad et al. on COPD and albuminuria in 53,129 patients showed that the risk for albuminuria increased significantly at lower levels of FEV1% predicted (p = 0.001). The majority (95.3%) of COPD patients without albuminuria had less severe COPD stages (GOLD stage of I and II) which is comparable to the findings in the current study [14].

Albuminuria in patients with COPD is also common in other associated co-morbidities including Chronic kidney disease (CKD), Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), and atherosclerosis as a result of systemic endothelial dysfunction. Patients with COPD have shown to have endothelial injury pathways in the lungs and kidneys [15]. One study reported the evidence of the glomerular damage by increased ACR; (0.80 mg/mmol versus 0.46 mg/mmol) in COPD and non-COPD patients respectively [16].

Studies elsewhere have shown a significantly increased frequency of renal injury in COPD population compared to the non-COPD population. CKD comorbidity occurs frequently in COPD patients. For instance, one case-control study reported a significant CKD prevalence in COPD compared to non-COPD groups; (31% vs 8% p < 0.001) based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFRCr), and (53% vs 15% p < 0.001) based on estimated cystatin C levels (eGFRCys). The odds ratio was 4.91 (95% CI, 1.94–12.46, P = 0.0008) and 6.30 (95% CI, 2.99–13.26, P = 0.0001) based on eGFRCr and eGFRCys respectively [17]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies reported increased odds of developing CKD (OR 2.20; 95% CI 1.83, 2.65) among COPD subjects compared to non-COPD subjects [18].

In this current study, the blood biomarkers for CKD, and other comorbidities were not carried out to ascertain their presence in COPD patients. A longitudinal study with thorough screening for these co-morbidities in order to explain their temporal association with COPD in the context of African patient cohort population is necessary, however.

This paper addressed the presence of albuminuria among African COPD patient cohort. COPD racial differences have not been well elucidated in the racial context. Literature is uncertain about COPD racial disparity due to differences in socioeconomic determinants risks for COPD. Limited available evidence reported that African-American with COPD is significantly younger and are less smoker. However, Africa-Americas have less emphysema than non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) but the same degree of airway disease. Furthermore, women of Africa-America ethnicity appear to be at higher risk of developing COPD than whites [19, 20].

It is common for people in low and middle-income countries including Africa to be exposed to biomass fuel/indoor pollution since childhood. Hence the mean age of COPD presentation in Africa is at the younger age some studies reported 35–45 years but also can be detected as early as the late teenage years. Women are the main cooks in the family and therefore are potentially vulnerable to particulate matters from biomass combustions. Young children less than 5 years of age do spend much time with their mothers hence are relatively equally exposed to biomass combustions [21,22,23,24]. Exposure to biomass fuel combustions is associated with increased prevalence of respiratory symptoms, reduced lung function and development COPD [25,26,27]. The domestic exposure to biomass fuel smoke in Tanzania and other African countries is alarmingly high. For instance, in Sub-Saharan Africa, the percentage of households using wood fuel varies from 86 to 99% in rural areas and 26–96% in urban areas. Overall 94% of African rural and 73% urban population used wood fuel (firewood and charcoal) as the primary source of energy [28].

Tanzania energy balance is dominated by biomass-based fuels, especially wood fuel (firewood and charcoal) which accounts for > 90% of primary energy supply [28]. More than 9 in 10 households (94%) use biomass fuels for cooking, heating, and lighting. Regarding tobacco use, less than 1 % of women (0.6%) smoke any tobacco while 14% of men smoke tobacco of which most of them smoke cigarettes on a daily basis [29]. Therefore, apart from tobacco smoking, the use of biomass fuels may be one of the important risk factors for COPD in Tanzania. The prevalence of COPD in Tanzania was conducted among 496 participants aged > 35 years in a rural setting by using spirometry diagnosis. Indoor and outdoor carbon monoxide (CO) levels from biomass fuel combustions were also measured. The overall prevalence of COPD was 17.5% of which 21.7% in males and 12.9% in females [30].

Study limitations

The study had the following limitations; first, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity classification was done only in newly diagnosed patients; this could underestimate it association with albuminuria in the context of sample size studied. For known COPD patients, it was difficult to stop their medications and arrange consecutively 2 days’ visits for assessing disease severity. Second, the use of history alone to describe the existence of comorbidity might have underestimated the existence of other conditions may cause albuminuria. A budget was not sufficient to cater for blood biomarker analysis.

Conclusion

A large proportion of study participants who were assed for COPD severity had moderate and severe COPD. Albuminuria was prevalent in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and it increased significantly with COPD severity. All study participants with CVD had abnormal urine albumin (albuminuria and proteinuria). Screening for albuminuria in COPD patients can be used as an early marker of CVD risk and therefore prevention strategies can be planned. A longitudinal study to further explain the pattern of albuminuria among the black population is highly needed in order to have a better comparison with previous studies done among Caucasian and Oriental populations.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

Albumin Creatinine ratio

- ATS:

-

American Thoracic Society

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- BP:

-

Blood Pressure

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular Disease

- eGFRCr:

-

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- eGFRCys:

-

Estimated Cystatin C

- ERS:

-

European Respiratory Society

- FEV1:

-

Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second

- FVC:

-

Forced Vital Capacity

- MI:

-

Myocardial Infarction

- MNH:

-

Muhimbili National Hospital

- PAH:

-

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United State of America

- UTI:

-

Urinary Tract Infections

References

World Health Organization. World health statistics 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43890.

Mehmood K, Sofi FA. Microalbuminuria and hypoxemia in patients with COPD. J Pulm Respir Med. 2015; https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-105X.1000280.

Barr RG, Celli BR, Mannino DM, Petty T, Rennard SI, Sciurba FC, et al. Comorbidities, patient knowledge, and disease management in a national sample of patients with COPD. Am J Med. 2009;122(4):348–55.

Anant RC, Patel JR, et al. Extrapulmonary comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: State of the art. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5(5):647–62.

de Lucas-Ramos P, Izquierdo-Alonso JL, Rodriguez-Gonzalez Moro JM, Frances JF, Lozano PV, Bellón-Cano JM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a cardiovascular risk factor – result from a case control (CONSISTE study). Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012; https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S36222.

Casanova C, de Torres JP, Navarro J, Aguirre-Jaíme A, Toledo P, Cordoba E, et al. Microalbuminuria and hypoxemia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(8):1004–10.

Kumar R. Study of Microalbuminuria in Patients with Stable COPD. Ann Int Med Dent Res. 2016; https://doi.org/10.21276/aimdr.2016.2.3.24.

Skloot GS, Edwards NT, Enright PL. Four-year calibration stability of the EasyOne portable spirometer. Respir Care. 2010;55(7):873–7.

Barr RG, Stemple KJ, Mesia-Vela S, Basner RC, Derk SJ, Henneberger PK, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a handheld spirometer. Respir Care. 2008;53(4):433–41.

Walters JAE, Wood-Baker R, Walls J, Johns DP. Stability of the EasyOne ultrasonic spirometer for use in general practice. Respirology. 2006;11(3):306–10.

DFI Care. www.dficare.com/en/bbs/board.php?bo_table=cybow_en&wr_id=5. Accessed 18 July 2018.

Efundem NT, Assob JCN, Feteh VF, Choukem SP. Prevalence and associations of microalbuminuria in proteinuria-negative patients with type 2 diabetes in two regional hospitals in Cameroon: A cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):6–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2804-5.

Casanova C, Celli BR. Microalbuminuria as a potential novel cardiovascular biomarker in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(4):951–3.

Romundstad S, Naustdal T, Romundstad PR, Sorger H, Langhammer A. COPD and microalbuminuria: a 12-year follow-up study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(4):1042–50.

Polverino F, Celli BR, Owen CA. COPD as an endothelial disorder: endothelial injury linking lesions in the lungs and other organs. Pulm Circ. 2018;8(1):1–18.

John M, Hussain S, Prayle A, Simms R, Cockcroft JR, Bolton CE. Target renal damage: the microvascular associations of increased aortic stiffness in patients with COPD. Respir Res. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-14-31.

Yoshizawa T, Hosokawa Y, Hashimoto S, Okada K, Furuichi S, Ishiguro T, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney diseases in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: assessment based on glomerular filtration rate estimated from creatinine and cystatin C levels. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1283–9.

Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Lohr JW, Arora P. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):158.

Hansel NN, Washko GR, Foreman MG, Han MK, Hoffman EA, Demeo DL, et al. Racial differences in CT phenotypes in COPD. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2013;10(1):20–7.

Kamil F, Pinzon I, Foreman MG. Sex and race factors in early-onset COPD. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(2):140–4.

Gordon S, Bruce N, Grigg J, Hibberd P, Kurmi O, Lam K, et al. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(10):823–60.

Van Gemert F, Kirenga B, Chavannes N, Kamya M, Luzige S, Musinguzi P, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated risk factors in Uganda (FRESH AIR Uganda): a prospective cross-sectional observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(1):e44–51.

Salvi S. The silent epidemic of COPD in Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(1):e6–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70359-6.

Kurmi OP, Devereux GS, Smith WCS, Semple S, Steiner MFC, Simkhada P, et al. Reduced lung function due to biomass smoke exposure in young adults in rural Nepal. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(1):25–30.

da Silva LFF, Saldiva SRDM, Saldiva PHN, Dolhnikoff M. Impaired lung function in individuals chronically exposed to biomass combustion. Environ Res. 2012;112:111–7.

Kilabuko JH, Nakai S. Effects of cooking fuels on acute respiratory infections in children in Tanzania. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2007;4(4):283–8.

Hu G, Zhou Y, Tian J, Yao W, Li J, Li B, et al. Risk of COPD from exposure to biomass smoke: A metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;138(1):20–31. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2114.

Lusambo LP. Household Energy Consumption Patterns in Tanzania. J Ecosyst Ecography. 2016;01 https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7625.S5-007.

Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland], Ministry of Health (MoH) [Zanzibar], National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), and ICF. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015-16. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: MoHCDGEC, MoH, NBS, OCGS, and ICF. 2016.

Magitta NF, Walker RW, Apte KK, Shimwela MD, Mwaiselage JD, Sanga AA, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and clinical correlates of COPD in a rural setting in Tanzania. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(2) https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00182-2017.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Almighty God for His Everlasting Mercy throughout the entire duration of this study. We are thankful to all study participants/patients who consented to the study. We thank all staffs of Internal Medicine of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, for their different opinions during results dissemination. We are thankful for the following for their technical assistance in this study; Dr. Simon Mamuya – Head department of environment science – school of public health and social sciences of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences for lending us a spirometer, Dr. R. Mpembeni – Public health specialist and biostatistician at school of public health and social sciences of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences and Mr. Amandus Kimario – independent statistician and mathematician – amanduskimario@gmail.com for their statistical assistance. We thank Dr. Hussein Mwanga – Occupational Health Physician at School of Public Health and Social Sciences of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dr. Paulina Chale – Pulmonologist at the Muhimbili National Hospital and Sr. Anneth Kweyunga – a nurse at pulmonary functions laboratory of the Muhimbili National Hospital.

Funding

I requested and granted a supporting fund during data collection and analysis from my employer - Muhimbili National Hospital, P.O Box 65000, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Patients confidential information will be removed, however.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors have read and approved the manuscript. 1. FKS. This is my original work as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Medicine (Internal Medicine) of Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences. I fully involved in the conception, development, data collection, analysis and report writing of this study. My manuscript was selected for presentation at two scientific conferences; the Muhimbili university annual scientific conference of 2017, and the Tanzania health summit of 2017. 2. JL. She is a consultant physician/endocrinologist, and Professor of Medicine at the department of internal medicine of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences. She was involved in study conception, methodology, and interpretation of the results. She was also involved in manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences Senate Research and Publication Committee. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Muhimbili National Hospital department of research. A written informed consent was obtained from all study participants and confidentiality was observed. Patients identified with a risk of extra-pulmonary comorbidity were referred to an appropriate discipline for further management.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests (declaration form are available for each author in case they are needed).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shayo, F.K., Lutale, J. Albuminuria in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional study in an African patient cohort. BMC Pulm Med 18, 125 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0694-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0694-5