Abstract

Background

This study aimed to investigate clinical characteristics of Korean PAP patients and to examine the potential risk factors of PAP.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed medical records of 78 Korean PAP patients diagnosed between 1993 and 2014. Patients were classified into two groups according to the presence/absence of treatment (lavage). Clinical and laboratory features were compared between the two groups.

Results

Of the total 78 PAP patients, 60% were male and median age at diagnosis was 47.5 years. Fifty three percent were ever smokers (median 22 pack-years) and 48% had a history of dust exposure (metal 26.5%, stone or sand 20.6%, chemical or paint 17.7%, farming dust 14.7%, diesel 14.7%, textile 2.9%, and wood 2.9%). A history of cigarette smoking or dust exposure was present in 70.5% of the total PAP patients, with 23% having both of them. Patients who underwent lavage (n = 38) presented symptoms more frequently (38/38 [100%] vs. 24/40 [60%], P < 0.001) and had significantly lower PaO2 and DLCO with higher D(A-a)O2 at the onset of disease than those without lavage (n = 40) (P = 0.006, P < 0.001, and P = 0.036, respectively). Correspondingly, the distribution of disease severity score (DSS) differed significantly between the two groups (P = 0.001). Based on these, when the total patients were categorized according to DSS (low DSS [DSS 1–2] vs. high DSS [DSS 3–5]), smoking status differed significantly between the two groups with the proportion of current smokers significantly higher in the high DSS group (11/22 [50%] vs. 7/39 [17.9%], P = 0.008). Furthermore, current smokers had meaningfully higher DSS and serum CEA levels than non-current smokers (P = 0.011 and P = 0.031), whereas no difference was found between smokers and non-smokers. Regarding type of exposed dust, farming dust was significantly associated with more severe form of PAP (P = 0.004).

Conclusion

A considerable proportion of PAP patients had a history of cigarette smoking and/or dust exposure, suggestive of their possible roles in the development of PAP. Active cigarette smoking at the onset of PAP is associated with the severity of PAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) is a rare disease characterized by the accumulation of excessive surfactant lipids and proteins within alveoli, leading to the impairment of gas exchange [1,2,3]. Clinical manifestations vary from no symptoms to progressive respiratory failure [3, 4]. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) deficiencies or defects in GM-CSF receptors are known to be related to the pathogenesis. GM-CSF is required for the terminal differentiation of alveolar macrophages (AMs) which play a key role in the clearance of normal surfactant proteins and phospholipids. Three different forms of PAP have been identified: idiopathic (primary or autoimmune), secondary, and hereditary [3,4,5,6]. More than 90% of PAP patients have idiopathic PAP (iPAP), a primary acquired disorder without familial predisposition in which GM-CSF neutralizing auto-antibodies are present [4, 7]. Secondary PAP is associated with various underlying diseases (hematologic malignancies, immunodeficiency disorders, infections) or inhalation injuries that cause AM dysfunction or deficiency in AM number [4, 8]. Hereditary PAP results from homozygous mutations of the genes encoding surfactant proteins and the ABCA3 transporter or from defects of the GM-CSF receptor [9].

To date, there have been several cross-sectional or retrospective studies enrolling a large cohort of PAP patients [10,11,12,13]. Although the studies have shown similar results in the distribution of age, male predominance, clinical manifestations and treatment methods, there have been demonstrated differences in suspected risk factors of PAP such as smoking and dust exposure.

Therefore, our present study aimed to investigate clinical characteristics of Korean PAP patients and to examine the potential risk factors of PAP with a focus on smoking and dust exposure.

Methods

Study participants

The Korean Interstitial Lung Disease Study Group retrospectively reviewed the medical records of PAP patients diagnosed between 1993 and 2014. The data were collected from 15 tertiary referral hospitals as a national multi-center survey.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Severance Hospital (IRB approval number: 4–2009-0372). As this was a retrospective study, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PAP was based on diagnostic bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) finding [14, 15], characteristic radiologic findings, and/or histopathologic findings of specimens obtained by surgical lung biopsy or transbronchial biopsy (TBB) and/or cytologic findings in BAL samples. Characteristic radiologic findings showed interlobular septal thickening in multiple lobes and/or diffuse, patchy, geographic appearance of ground glass opacities [16]. Diagnostic histopathologic findings included intraalveolar eosinophilic, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive material, intracellular surfactant inclusion bodies in AMs, and turbid, PAS-positive, eosinophilic BAL fluid [14, 15].

Data collection

Baseline characteristics of the patients including age, sex, smoking status, and the presence/absence of symptoms at initial disease onset were investigated based on the medical chart review, while data on a history of dust exposure were obtained through a detailed survey of an occupational history in patients with PAP. Patients were classified into 3 categories based on the smoking status in Tables 3 and 4 (never smokers, ex-smokers, and current smokers). Additional analyses were conducted according to the presence/absence of current active smoking at the time of PAP diagnosis (Fig. 3a; current smokers vs. non-current smokers) or smoking history itself including past and current smoking (Fig. 3b; smokers vs. non-smokers). ‘Non-current smokers’ included both never-smokers and ex-smokers as contrasted with ‘current smokers’ and ‘smokers’ included both ex-smokers and current smokers. The extent and the pattern of radiologic lung involvements, blood gas analyses, pulmonary function test (PFT) results including diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and forced vital capacity (FVC), and the levels of known serum biomarkers including lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [5, 10, 12, 17,18,19,20,21] and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) [10, 12, 20, 22,23,24,25] at the time of diagnosis were also investigated. We attained additional data on blood gas analyses and PFT results following therapeutic lavage where possible.

Assessment of disease severity score

Each patient was assigned a PAP disease severity score (DSS) based on the presence/absence of symptoms and the degree of PaO2 at initial diagnosis, as previously described [25]. The categories of score ranged from DSS 1 to DSS 5: DSS 1 = no symptoms and PaO2 ≥ 70 mmHg, DSS 2 = symptomatic and PaO2 ≥ 70 mmHg, DSS 3 = 60 mmHg ≤ PaO2 < 70 mmHg, DSS 4 = 50 mmHg ≤ PaO2 < 60 mmHg, DSS 5 = PaO2 < 50 mmHg.

Statistics

Parametric data were presented as mean (± standard deviation) and nonparametric data as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as either percentage of the total or number as appropriate. Numeric data were compared using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test, and categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. The degree of correlation between variables was evaluated using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Results

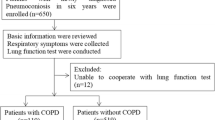

Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 78 patients from multiple centers in Korea were enrolled including 75 patients with iPAP and 3 patients with secondary PAP with underlying diseases such as lung cancer, lymphoma, and pulmonary tuberculosis. The median age at diagnosis was 47.5 years. Forty-seven (60%) patients were male and 39 (53%) patients were ever smokers. Sixty-two (80%) patients were symptomatic at diagnosis of PAP. The proportion of patients with low DSS (DSS 1–2) was higher compared with that of patients with high DSS (DSS 4–5) (65% vs. 11%). Thirty-four (48%) patients had a history of dust exposure. The types and the composition of exposed dust are presented as Fig. 1. A history of cigarette smoking or dust exposure was present in 55 (71%) patients with PAP, with 18 (23%) patients having both of them. Thirty-two (41%) patients exhibited diffuse bilateral lung involvements and 32 (64%) of the evaluable 50 patients typical crazy paving appearance in their radiologic findings. 35 (45%) patients were diagnosed through surgical lung biopsy while 43 (55%) patients through TBB with BAL alone (Table 2). Regarding treatment, 38 (49%) patients were treated with whole or segmental lung lavage whereas 30 (50%) patients were closely observed without active treatment. Most patients survived except for 3 patients with the causes of death including respiratory failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, and pneumonia. When a significant progression of respiratory symptoms with a subsequent application of additional therapeutic lavage was considered recurrence, PAP recurred in 11 (14%) of the total 78 patients during the follow-up period.

When we compared clinical and laboratory features between patients who received lavage and those who did not, patients with lavage more frequently experienced symptoms than did those without (100% vs. 60%, P < 0.001) (Table 3). In particular, presence of dyspnea was associated with treatment (90% vs. 40%, P < 0.001). Also, patients with lavage had significantly lower FVC (%), DLCO (%), and PaO2 levels and higher D(A-a)O2 level at initial manifestation (P = 0.005, P < 0.001, P = 0.006 and P = 0.036, respectively). Consequently, there was a meaningful difference in the distribution of DSS between patients who underwent lavage and those who did not (P = 0.001). Regarding type of exposed dusts, farming dust was significantly associated with treatment (P = 0.011).

When we classified the total patients into two groups (patients with low DSS [DSS 1–2] vs. patients with high DSS [DSS 3–5]) according to whether the patients had hypoxemia or not in arterial blood gas analyses at the time of diagnosis (Table 4), smoking status differed significantly between the two groups (P = 0.023). The proportion of current smokers were significantly higher in patients with high DSS than in those with low DSS (50% vs. 18%, P = 0.008). Regarding type of exposed dust, farming dust was significantly associated with high DSS (45% vs. 0%, P = 0.004).

Patients with high DSS had meaningfully lower FVC (%), DLCO (%), and PaO2 levels, and higher D(A-a)O2 level than those with low DSS. Furthermore, DSS was positively correlated with D(A-a)O2 (r = 0.746, P < 0.001) and inversely with PaO2 (r = −0.646, P < 0.001), DLCO (%) (r = −0.533, P < 0.001) and FVC (%) (r = −0.398, P = 0.002) (Fig. 2). However, DSS did not correlate with the known serum severity markers (DSS–LDH: r = −0.209; P = 0.222, DSS–CEA: r = 0.406; P = 0.215).

Further analysis revealed that current smokers had significantly higher DSS (Fig. 3a) and serum CEA levels than non-current smokers (DSS: 2.8 ± 0.9 vs. 2.2 ± 0.9; P = 0.011, CEA: 8.9 ± 8.2 ng/mL vs. 5.4 ± 7.6 ng/mL; P = 0.031), whereas serum LDH level was not different between the two groups. However, when we categorized patients into smokers and non-smokers, no difference was found between the two groups with regard to DSS (Fig. 3b), serum CEA, or LDH level.

Box and whisker plots of the distribution of DSS between (a) non-current smokers (n = 43) and current smokers (n = 18) and between (b) non-smokers (n = 27) and smokers (n = 34). The box represents the interquartile range that contains 50% of the values, and the whiskers extending from the box represent the highest and lowest values. The thick line in the box represents the median value. There was a significant difference in DSS between non-current smokers and current smokers (A, P = 0.011), whereas no difference was found between non-smokers and smokers (B, P = 0.328)

The total exposed dose of cigarette smoking (number of cigarette pack-years [PYs]) significantly correlated with indicators of PAP severity such as DSS (r = 0.567, P = 0.028), PaO2 (r = −0.597, P = 0.019), and D(A-a)O2 (r = 0.624, P = 0.017) in patients with both dust exposure and cigarette smoking history (n = 18). Such correlations were stronger in patients with both dust exposure and current active smoking at PAP diagnosis (n = 12; PY-PaO2: r = −0.627, P = 0.053; PY-D(A-a)O2: r = 0.724, P = 0.028).

Discussion

Our present study investigated clinical characteristics of Korean PAP patients over 20 years, and examined the potential risk factors of PAP with a focus on smoking and dust exposure.

We classified the total patients into two groups according to whether or not the patients were treated with lavage and analyzed the differences. Treated patients presented symptoms more frequently and had significantly lower PaO2 and DLCO (%) with higher D(A-a)O2 at the onset of disease than patients who were not treated. The presence of symptoms correlated with increased hypoxia and decreased diffusing capacity. Correspondingly, the distribution of DSS differed significantly between the two groups. Based on these results, we categorized all patients according to the level of DSS and discovered that current smoking is significantly associated with PAP severity. In support of this finding, we demonstrated that CEA levels, a biomarker for PAP severity, were higher in current smokers compared to non-current smokers. However, when we classified the patients into smokers and non-smokers, we could not find such a difference. Regarding type of exposed dust, farming dust was associated with more severe form of PAP.

Despite a few preexisting well-designed clinical studies, no other studies have demonstrated a relationship between cigarette smoking and PAP. Seymour and colleagues reported in their meta-analysis that 72% of PAP patients were smokers with male predominance, but no differences were found regarding symptoms, serum LDH level, PaO2, or D(A-a)O2 between smokers and non-smokers [5]. Also, one study from Germany reported that, among 70 PAP patients over a 30-year period, 79% were smokers [12], contrasting with 56% of 248 patients in a Japanese national study [10]. Although the proportion of smokers varies, all the above-mentioned studies have analyzed the difference between smokers and non-smokers and could not prove an association between smoking and PAP. However, our study revealed that active smoking at the onset of disease but not past smoking is associated with the severity of PAP, although it is not clear that cigarette smoking itself initiates or induces PAP. That might explain the study result of Bonella et al. in which active current smokers required a higher number of whole lung lavages for achieving remission than did non-smokers [12].

Then, what is the possible mechanism by which cigarette smoking affects the severity of PAP? First of all, it is notable that some similarities exist between PAP and other antibody-mediated systemic diseases with pulmonary manifestations such as Goodpasture’s syndrome. A causative relationship between active smoking and Goodpasture’s syndrome has been proposed in several previous studies based on the fact that a high proportion of patients with lung hemorrhage were active smokers. They suggested the possibility that cigarette smoke could increase the permeability of lung capillaries to allow preformed circulating antibodies to reach the alveolar basement membrane (ABM), or that smoking and other inhaled toxins could alternatively change antigenic determinants in the ABM, inducing formation of anti-ABM antibodies or enabling them to cross-react with anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibodies [26, 27]. Moreover, similar to the former mechanism, some preclinical studies have shown that a high concentration of inspired oxygen or hydrocarbon fumes can induce permeability changes in lung capillaries [28,29,30].

It has also recently been demonstrated that cigarette smoke not only alters epithelial barrier functions, but also directly induces endothelial cell barrier disruption via oxidative stress-dependent and ceramide-mediated cytoskeletal changes in a dose- and time-dependent manner [31]. While breaches of the epithelial barrier might induce wound-repair inflammatory responses, disruption of the endothelial barrier can directly increase access of circulating proteins, plasma, and inflammatory cells to the interstitium and alveolar spaces [31,32,33,34]. Therefore, by inducing direct changes in the permeability of the lung capillaries, cigarette smoking can presumably enable preformed antibodies (Abs) like anti-GM-CSF Abs to leak out through the lung capillaries to reach alveolar spaces, causing iPAP. Due to the dose-dependent relationship between cigarette smoke and endothelial layer damage, we can speculate that PAP severity would change according to the amount of smoking. In consonance with this, our present study showed that significant correlations were observed between the total exposed dose of cigarette smoking and indicators of PAP severity in patients with both dust exposure and cigarette smoking history.

Prior studies of Lin et al. also revealed that, whereas the level of serum anti-GM-CSF Abs did not correlate with severity of iPAP, the level of anti-GM-CSF Abs in BAL fluid directly correlated with disease severity markers such as serum LDH, PaO2, D(A-a)O2 and DLCO, further predicting the need for subsequent therapeutic lavage, which implies the interrelation between degree of alveolar capillary damage and severity of iPAP [19, 21].

Meanwhile, serum LDH, KL-6, and CEA are well-established biomarkers related to severity of PAP which reflect alveolar epithelial cell damage to a certain degree [18, 22,23,24,25]. In the present study, although mean serum CEA level was elevated in both current and non-current smokers, currently smoking patients had significantly higher serum CEA level than non-current smokers (P = 0.031). However, there was no difference between smokers and non-smokers, similar to the previous result of Fujishima et al. [22], supporting that active smoking at the onset of PAP but not past smoking is associated with more severe disease manifestations. In addition, considering that serum CEA level is associated with smoking in a dose-dependent manner, however, after cessation of smoking, elevated CEA level decreases to the range of non-smokers [35, 36], the well-established relationship between serum CEA level and iPAP severity should be reappraised in terms of that between current smoking and severity of iPAP.

Regarding type of dust exposure, farming dust was associated with more severe form of PAP in our present study, although other types of exposed dusts revealed not to be associated with PAP severity, presumably due to the small number of patients. In possible relation to this, some preclinical studies have shown that the degree of lung injury differs according to the type and degree of dust exposure [17, 37,38,39,40]. Although several case studies showing the effects of dust exposure on PAP have been reported to date [41,42,43,44,45], extensive clinical studies enrolling a large number of PAP patients are needed to confirm this finding.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, it was not possible to measure the level of serum anti-GM-CSF Abs, although idiopathic PAP in this study could be assumed to be autoimmune PAP. Second, this was a retrospective observational study that included a small number of PAP cases with information on dust exposure obtained from limited occupational history. However, considering the rare incidence of PAP, this study is notable because, as a multi-center study conducted in one country, it focused on the possible risk factors of PAP and demonstrated the effects of cigarette smoking on PAP severity for the first time. Further studies are needed to determine whether cigarette smoking can directly induce PAP and to demonstrate the effects of dust exposure on PAP severity in a large PAP cohort.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a considerable proportion of PAP patients had a history of cigarette smoking and/or dust exposure, suggestive of their possible roles in the development of PAP. Active cigarette smoking at the onset of PAP is associated with the severity of PAP.

Abbreviations

- Ab:

-

Antibody

- ABM:

-

Alveolar basement membrane

- AM:

-

Alveolar macrophage

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- DLCO :

-

Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

- DSS:

-

Disease severity score

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GM-CSF:

-

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- iPAP:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- PAP:

-

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

- PFT:

-

Pulmonary function test

- WLL:

-

Whole lung lavage

References

Rosen SH, Castleman B, Liebow AA. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 1958;258(23):1123–42.

Borie R, Danel C, Debray MP, Taille C, Dombret MC, Aubier M, Epaud R, Crestani B. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(120):98–107.

Shah PL, Hansell D, Lawson PR, Reid KB, Morgan C. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: clinical aspects and current concepts on pathogenesis. Thorax. 2000;55(1):67–77.

Trapnell BC, Whitsett JA, Nakata K. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(26):2527–39.

Seymour JF, Presneill JJ. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: progress in the first 44 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(2):215–35.

Carey B, Trapnell BC. The molecular basis of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Clin Immunol (Orlando, Fla). 2010;135(2):223–35.

Kitamura T, Uchida K, Tanaka N, Tsuchiya T, Watanabe J, Yamada Y, Hanaoka K, Seymour JF, Schoch OD, Doyle I, et al. Serological diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(2 Pt 1):658–62.

Chaulagain CP, Pilichowska M, Brinckerhoff L, Tabba M, Erban JK. Secondary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in hematologic malignancies. Hematol/oncology and stem cell therapy. 2014;7(4):127–35.

Whitsett JA, Wert SE, Trapnell BC. Genetic disorders influencing lung formation and function at birth. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13 Spec No 2:R207–15.

Inoue Y, Trapnell BC, Tazawa R, Arai T, Takada T, Hizawa N, Kasahara Y, Tatsumi K, Hojo M, Ichiwata T, et al. Characteristics of a large cohort of patients with autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in Japan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(7):752–62.

Xu Z, Jing J, Wang H, Xu F, Wang J. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in China: a systematic review of 241 cases. Respirology (Carlton, Vic). 2009;14(5):761–6.

Bonella F, Bauer PC, Griese M, Ohshimo S, Guzman J, Costabel U. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: new insights from a single-center cohort of 70 patients. Respir Med. 2011;105(12):1908–16.

Byun MK, Kim DS, Kim YW, Chung MP, Shim JJ, Cha SI, ST U, Park CS, Jeong SH, Park YB, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in Korean population. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(3):393–8.

Schoch OD, Schanz U, Koller M, Nakata K, Seymour JF, Russi EW, Boehler A. BAL findings in a patient with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis successfully treated with GM-CSF. Thorax. 2002;57(3):277–80.

Wang BM, Stern EJ, Schmidt RA, Pierson DJ. Diagnosing pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. A review and an update. Chest. 1997;111(2):460–6.

Holbert JM, Costello P, Li W, Hoffman RM, Rogers RM. CT features of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(5):1287–94.

Adamis Z, Tatrai E, Honma K, Ungvary G. Vitro and in vivo assessment of the pulmonary toxicity of cellulose. J Applied Toxicol : JAT. 1997;17(2):137–41.

Hoffman RM, Rogers RM. Serum and lavage lactate dehydrogenase isoenzymes in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143(1):42–6.

Seymour JF, Doyle IR, Nakata K, Presneill JJ, Schoch OD, Hamano E, Uchida K, Fisher R, Dunn AR. Relationship of anti-GM-CSF antibody concentration, surfactant protein a and B levels, and serum LDH to pulmonary parameters and response to GM-CSF therapy in patients with idiopathic alveolar proteinosis. Thorax. 2003;58(3):252–7.

Tazawa R, Trapnell BC, Inoue Y, Arai T, Takada T, Nasuhara Y, Hizawa N, Kasahara Y, Tatsumi K, Hojo M, et al. Inhaled granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor as therapy for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(12):1345–54.

Lin FC, Chang GD, Chern MS, Chen YC, Chang SC. Clinical significance of anti-GM-CSF antibodies in idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Thorax. 2006;61(6):528–34.

Fujishima T, Honda Y, Shijubo N, Takahashi H, Abe S. Increased carcinoembryonic antigen concentrations in sera and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids of patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Respir; Int Rev Thoracic Dis. 1995;62(6):317–21.

Fang SC, KH L, Wang CY, Zhang HT, Zhang YM. Elevated tumor markers in patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51(7):1493–8.

Hirakata Y, Kobayashi J, Sugama Y, Kitamura S. Elevation of tumour markers in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(5):689–96.

Inoue Y, Nakata K, Arai T, Tazawa R, Hamano E, Nukiwa T, Kudo K, Keicho N, Hizawa N, Yamaguchi E, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in Japan. Respirol (Carlton, Vic). 2006;11 Suppl:S55–60.

Donaghy M, Rees AJ. Cigarette smoking and lung haemorrhage in glomerulonephritis caused by autoantibodies to glomerular basement membrane. Lancet (London, England). 1983;2(8364):1390–3.

Herody M, Duvic C, Noel LH, Nedelec G, Grunfeld JP. Cigarette smoking and other inhaled toxins in anti-GBM disease. Contrib Nephrol. 2000;130:94–102.

Keller F, Nekarda H. Fatal relapse in Goodpasture's syndrome 3 years after plasma exchange. Resp; Int Rev Thorac Dis. 1985;48(1):62–6.

Jennings L, Roholt OA, Pressman D, Blau M, Andres GA, Brentjens JR. Experimental anti-alveolar basement membrane antibody-mediated pneumonitis. I. The role of increased permeability of the alveolar capillary wall induced by oxygen. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950). 1981;127(1):129–34.

Yamamoto T, Wilson CB. Binding of anti-basement membrane antibody to alveolar basement membrane after intratracheal gasoline instillation in rabbits. Am J Pathol. 1987;126(3):497–505.

Schweitzer KS, Hatoum H, Brown MB, Gupta M, Justice MJ, Beteck B, Van Demark M, Gu Y, Presson RG Jr, Hubbard WC, et al. Mechanisms of lung endothelial barrier disruption induced by cigarette smoke: role of oxidative stress and ceramides. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301(6):L836–46.

Low B, Liang M, Fu J. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates sidestream cigarette smoke-induced endothelial permeability. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;104(3):225–31.

Burns AR, Hosford SP, Dunn LA, Walker DC, Hogg JC. Respiratory epithelial permeability after cigarette smoke exposure in guinea pigs. J Applied Physiol (Bethesda, Md: 1985). 1989;66(5):2109–16.

Li XY, Donaldson K, Rahman I, MacNee W. An investigation of the role of glutathione in increased epithelial permeability induced by cigarette smoke in vivo and in vitro. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(6):1518–25.

Alexander JC, Silverman NA, Chretien PB. Effect of age and cigarette smoking on carcinoembryonic antigen levels. JAMA. 1976;235(18):1975–9.

Stevens DP, Mackay IR. Increased carcinoembryonic antigen in heavy cigarette smokers. Lancet (London, England). 1973;2(7840):1238–9.

Xu H, Vanhooren HM, Verbeken E, Yu L, Lin Y, Nemery B, Hoet PH. Pulmonary toxicity of polyvinyl chloride particles after repeated intratracheal instillations in rats. Elevated CD4/CD8 lymphocyte ratio in bronchoalveolar lavage. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;194(2):122–31.

Ellakkani MA, Alarie YC, Weyel DA, Mazumdar S, Karol MH. Pulmonary reactions to inhaled cotton dust: an animal model for byssinosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984;74(2):267–84.

Milton DK, Godleski JJ, Feldman HA, Greaves IA. Toxicity of intratracheally instilled cotton dust, cellulose, and endotoxin. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142(1):184–92.

Warheit DB, Hansen JF, Yuen IS, Kelly DP, Snajdr SI, Hartsky MA. Inhalation of high concentrations of low toxicity dusts in rats results in impaired pulmonary clearance mechanisms and persistent inflammation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;145(1):10–22.

Cummings KJ, Donat WE, Ettensohn DB, Roggli VL, Ingram P, Kreiss K. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in workers at an indium processing facility. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(5):458–64.

Costabel U, Nakata K. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis associated with dust inhalation: not secondary but autoimmune? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(5):427–8.

Hisata S, Moriyama H, Tazawa R, Ohkouchi S, Ichinose M, Ebina M. Development of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis following exposure to dust after the great East Japan earthquake. Respiratory investigation. 2013;51(4):212–6.

Miller RR, Churg AM, Hutcheon M, Lom S. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and aluminum dust exposure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130(2):312–5.

Thind GS. Acute pulmonary alveolar proteinosis due to exposure to cotton dust. Lung India: official organ of Indian Chest. Society. 2009;26(4):152–4.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all members of The Korean ILD Study Group who helped gather the data for analysis.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAH conceived and designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the result and drafted and revised the manuscript. JHS, JHK, MPC, DSK, JWS, YWK, SMC, SIC, STU, CSP, SHJ, YBP, HLL, JWS, EJC, YJ, HKL, JSP participated in the designing of the study, gathering the data, interpretation of the result, and drafting and revising the work. MSP conceived of the study, participated in the design and coordination, interpreted the result and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Severance Hospital (IRB approval number: 4–2009-0372). As this was a retrospective study, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, J., Song, J., Kim, J. et al. Clinical significance of cigarette smoking and dust exposure in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a Korean national survey. BMC Pulm Med 17, 147 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0493-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0493-4