Abstract

Background

Legal access to medical cannabis is increasing world-wide. Despite this, there is a lack of evidence surrounding its efficacy on mental health outcomes, particularly, on depression. This study assesses the effect of medical cannabis on Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scores in adult patients between 2014 and 2019 in Ontario and Alberta, Canada.

Methods

An observational cohort study of medically authorized cannabis patients in Ontario and Alberta. Overall change in PHQ-9 scores from baseline to follow-up were evaluated (mean change) over a time period of up to 3.2 years.

Results

37,338 patients from the cohort had an initial PHQ-9 score recorded with 5103 (13.7%) patients having follow-up PHQ-9 scores. The average age was 54 yrs. (SD 15.7), 46% male, 50% noted depression at baseline. The average PHQ-9 score at baseline was 10.5 (SD 6.9), following a median follow-up time of 196 days (IQR: 77–451) the average final PHQ-9 score was 10.3 (SD 6.8) with a mean change of − 0.20 (95% CI: − 0.26, − 0.14, p-value < 0.0001). Overall, 4855 (95.1%) had no clinically significant change in their PHQ-9 score following medical cannabis use while 172 (3.4%) reported improvement and 76 (1.5%) reported worsening of their depression symptoms.

Conclusions

Although the majority showed no clinically important changes in PHQ-9 scores, a number of patients showed improvement or deteriorations in PHQ-9 scores. Future studies should focus on the parallel use of screening questionnaires to control for PHQ-9 sensitivity and to explore potential factors that may have attributed to the improvement in scores pre- and post- 3-6 month time period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The medical use of cannabis has become a world-wide phenomenon – with increasing numbers of jurisdictions allowing patient access to cannabis for a variety of therapeutic interventions [1]. Canadians have had legal access to medical cannabis [2] for its treatment of a variety of health conditions [3], including for the improvement of mental health outcomes [4,5,6]. Despite its availability, significant evidence gaps remain, particularly for depression and depression-related health outcomes [7,8,9,10,11]. Indeed, there is a lack of rigorous large-patient cohort studies on medical cannabis that utilize standardized validation tools on determining its impact on mental health [12, 13].

Pre-existing clinical studies and systematic reviews on medical cannabis’ impact on depression and depression-related outcomes show mixed results. To date, the most recent clinical recommendations from both Canada and the US (based on the best-available evidence) [14, 15] report that there is limited evidence on cannabis’ efficacy in improving depression symptoms. Importantly, few studies have directly studied the effect of medical cannabis solely on depression [16,17,18,19]. Rather, the majority of studies categorize depression under the broad category of mental health outcomes [5, 20, 21]. Furthermore, the studies on depression are themselves, limited, as very few utilize the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [22] as a gold standard for measuring depression outcomes [19, 23, 24]. Likewise, these studies are predominantly designed with small cohort sample sizes [25], focus on how cannabis consumption may cause/develop depression [26, 27] - rather than improve it [13, 28]; very few differentiate medical cannabis use from nonmedical use [29]; and lastly, studies frequently emphasize the limitations of inferences made between medical cannabis and depression due to contemporaneous use of other drugs or illegal substances amongst participants [13, 30]. Thus, this study was designed to provide clarity of the potential impact of medical cannabis on depression and depression-related health outcomes by measuring changes in patients’ PHQ-9 scores over time.

Methods

Study design

Cohort study of patients in Alberta and Ontario, Canada who were authorized medical cannabis between 2014 and 2019.

Study population

Inclusion criteria

The study population consisted of all adult patients authorized to access medical cannabis attending a chain of specialized clinics in the provinces of Alberta and Ontario (Canada). Participants were adults of any sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status who were seeking medical cannabis for any reason. Patients may choose to seek assessment for medical cannabis through the clinic via a self-referral or by a physician referral.

Exclusion criteria

All patients without a PHQ-9 questionnaire at baseline (i.e., at time of medical cannabis authorization), and those without at least one score from any point during the follow-up period were excluded as we were most interested in the changes in the PHQ-9 over time.

Data source

Informed signed consent was provided by the patient at the time of first referral which allowed data to be collected and used for clinical and research purposes. All data was released as de-identified data to the researchers. The self-reported outcomes and physician-based medical assessments were collected from adult patients at cannabis clinics in Alberta and Ontario, Canada who have been authorized to use medical cannabis. As part of the intake process, each patient seeking medical cannabis meets with a counselor who performs an initial assessment and collects relevant data. All patients must provide sociodemographic information and disclose their primary medical complaints that constitute their rationale for requesting a medical cannabis authorization. In addition, patients completed several validated questionnaires at baseline, including: pain questionnaires [31, 32], the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale [33]; Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [22]; and the CAGE Questionnaire Adapted to Include Drugs (CAGE-AID) [34], among others. Informed consent is provided by the patient at the time of first referral, which allows data to be collected and used by the clinics. Following their initial intake interview, the patient is referred to a physician who makes their assessment based on the self-reported information as well as the patient’s health record. All data was released as de-identified data.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design, conduct and reporting of this research project as it was not applicable to this project.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics board (PRO 00068887) and Veritas Research Ethics Board in Ontario (16111–13:21:103–01-2017). Informed signed consent is provided by the patient at the time of first referral, which allows data to be collected and used by Canadian Cannabis Clinics.

Outcomes

The PHQ-9 questionnaire is a self-administered tool for assessing depressive disorders [22] using nine items scored on their frequency from ‘not at all’ to ‘nearly every day’ resulting in a score between 0 and 27 (higher scores representing greater depressive symptoms). This method for assessing depression symptoms was chosen because many of the nine items align with the DSM-V criteria for identifying depressive disorders. The questionnaire is also straightforward and is often used clinically as the measure can be rapidly completed by patients to effectively assess depression symptoms [22]. The PHQ-9 has a reported sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for major depression. One major limitation of the PHQ-9 is that it only screens for depression and depression-related symptoms; it cannot diagnose Major Depressive Disorder or other depressive-like disorders. The justification for the use of the PHQ-9 was simply due to the fact that it was the main selected tool utilized by the physicians at the cannabis clinics to assess and screen for depression.

The PHQ-9 scores were also used to categorize the severity of the depression symptoms: score of 0–4 was no symptoms, 5–9 mild, 10–14 moderate, 15–19 moderately severe, and 19–27 severe symptoms. These are the depression categories that are recommended for use with the PHQ-9 questionnaire [22].

Covariates including age, sex, neighbourhood average income quintile, length of follow-up, reason for cannabis use, method of cannabis use, and antidepressant usage were considered. Neighbourhood average income was determined using census data matched to the patient’s area of residence. Length of follow-up was the number of days between the initial administration of the PHQ-9 and the follow-up administration of the PHQ-9. Reason for cannabis use was coded into the following categories: pain, mental health, autoimmune disorder, cancer, sleep problems, neurological disorder, gastrointestinal disorder, and other. The mental health category was further broken down to consider anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, panic disorder, and mood disorder. See Additional file 1 for the phrases used for coding the reasons for visit. Some patients did not record a reason for seeking medical cannabis so these patients were coded as having an unknown reason for use. Method of cannabis use was coded into ingesting, smoking, vaping, or topical use (see Additional file 1 for keywords used). Antidepressant usage was coded into the following categories: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), and other antidepressants. Other antidepressants included norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRI), noradnergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSA), and Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI). Patients were considered to have used antidepressants if any of these classes of medications were listed as current medications at any appointment during the patient’s care at the cannabis clinics(see Additional file 1 for a full list of medications included in each antidepressant category). Information on the frequency of use and dosage was not available. Both the method of cannabis use and antidepressant categories were not mutually exclusive as many patients use multiple methods to consume cannabis and multiple classes of antidepressants.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics using counts, percentages, means, and standard deviation were used to assess the patients’ demographics. The changes in PHQ-9 scores and depression categories were determined by subtracting the final PHQ-9 score from the initial PHQ-9 score. Therefore, a negative change in PHQ-9 represents a lessening of depression symptoms while a positive change in PHQ-9 represents an increase in depression symptoms. Any follow-up appointment where depression symptoms were reassessed was considered for analysis, therefore some subjects had multiple follow-up PHQ-9 scores for multiple follow-up appointments. The follow-up scores with the longest length of follow-up were used to assess changes in PHQ-9 scores and depression categorization. For the purpose of this study, we considered a 5-point change in PHQ-9 to be potentially clinically significant, as others have [35]. To examine the differences between the initial and final PHQ-9 scores and depression categories paired t-tests were conducted. A multiple linear regression was also conducted to assess the effects of covariates on their PHQ-9 scores. In addition, as the PHQ-9 is scored between 0 and 27, in instances where the recorded PHQ-9 score was outside of the plausible range, these scores were omitted from analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata version 15.1.

Sensitivity analysis

Follow-up time was broken in 6 categories to assess if length of exposure to cannabis had an effect on PHQ-9 scores. The time categories were as follows: less than 7 days, 1 week to 3 months, 3 to 6 months, 6 to 12 months, 1 to 2 years, and greater than 3 years. Post-hoc, we looked specifically at patients who reported depression at onset as well as patients who had at least 6 months of follow-up data to evaluate the change in PHQ-9 scores among these specific groups as clinically changes in depression generally do not occur rapidly in patients.

Results

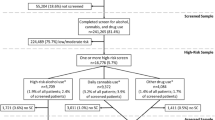

84,809 patients were authorized medical cannabis with 37,338 (44%) completing the PHQ-9 questionnaire at baseline and 5103 (6.0%) patients during the follow-up (Fig. 1). Multiple follow-up appointments occurred for some patients resulting in 5795 follow-up PHQ-9 scores from the 5103 patients.

Importantly, the characteristics of those with and without follow-up PHQ-9 scores were overall similar (Table 1) and the same distribution of depression categories existed. The reasons for seeking medical cannabis were also similar among those who did and did not have follow-up PHQ-9 scores with the top reasons being pain, autoimmune disorders, sleep problems, and mental health disorders. Among those seeking medical cannabis for mental health disorders (N = 12,883), 41.0% self-identified as having depression. 17,491 (47%) patients who completed the PHQ-9 questionnaire at baseline were using antidepressants to manage their depression symptoms while attending the cannabis clinics. The timing of follow-up appointments varied: 10.6% (less than 7 days), 26.0% (1 week to ≤ 3 months), 18.2% (3 to ≤ 6 months), 18.4% (6 to 12 months), 20.6% (1 to 2 years), and 6.2% (greater than 2 years) (Table 2). The median (IQR) time for all follow-up appointments was 196 days (77–451).

The average PHQ-9 score at baseline was 10.5 (SD 6.9). Following an average follow-up time of 255 days (SD: 250) (median: 196, IQR: 77–451), the average final PHQ-9 score was 10.3 (SD 6.8) with a mean change of − 0.20 (95% CI: − 0.26, − 0.14, p-value < 0.0001). Overall, most patients had minimal change in their PHQ-9 score (88.3%) or depression categorization (92.7%) (Table 3 & Additional file 2). However, of the 5103 followed-up patients, 172 (3.4%) had what would be considered a clinically important decrease of at least 5 points or more and 76 (1.5%) had an increase following medical cannabis use.

Subsequent analysis, based on patient’s initial depression classification showed similar results (Table 3 & Additional file 2), although the clinical importance of these changes is uncertain. For patients with severe depression (n = 648), 5.1% had a decrease of at least five points in their PHQ-9 score, the mean difference from initial to final appointment was − 0.70 (95% CI: − 0.94, − 0.46, p-value < 0.0001). For patients with moderately severe depression (N = 833), 4.9% had a decrease and 0.6% had an increase of at least five points in their PHQ-9 score, the mean difference was − 0.44 (95% CI: − 0.61, − 0.27, p-value < 0.0001). Conversely, for patients with no depression (N = 1181), 2.5% had an increase in their PHQ-9 score, the mean difference was 0.25 (95% CI: 0.14, 0.35, p-value < 0.0001).

The multiple linear regression analyses showed that initial PHQ-9 score, the presence of pain, mental health disorders, and depression at baseline, and the use of SSRIs were statistically associated with some change in PHQ-9 scores (Additional file 3). None of the individual coefficients contributed to a change in PHQ-9 score of at least five points suggesting that while they are statistically significant, they may not be clinically important.

Sensitivity analyses results

The follow-up period that had the most frequent changes in the depression categorization was 3 to 6 months following authorization (Fig. 2 and Table 4). Of the 1056 patients (20.7%) whose PHQ-9 score was re-assessed three to six-months following authorization, pronounced changes in scores included: 11.1% had a decrease and 5.6% had an increase in their depression categorization (Table 4). The mean difference in PHQ-9 score for this time period was − 0.47 (95% CI: − 0.67, − 0.27, p-value< 0.0001) (Table 2). While the majority of patients had no change in their depression categorization, for those that did experience a significant numeric change in score- there were roughly twice as many patients with a decrease in depression categorization than an increase, with the exception of the less than 7 days time period.

In our post-hoc analysis, medical cannabis authorization was not associated with a clinically important change in the PHQ-9 scores among those with initial depression classification of moderate to severe. Among these 2550 patients, the mean change in PHQ-9 score was − 0.49 (95% CI: − 0.59, − 0.39, p-value< 0.0001). When restricting the analysis to patients with a follow-up of greater than 6 months (n = 2616) there remained no clinically important change in PHQ-9, mean change in PHQ-9 score: -0.30 (95% CI: − 0.39, − 0.20, p-value< 0.0001).

Discussion

This population-based study of patients in Ontario and Alberta authorized for medical cannabis showed some clinical impact on depression symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9, in particular, 20.7% (1056) of patients - whose PHQ-9 score was re-assessed 3 to 6-months following authorization – reported a significant change in scores. However, at the population level, the overall majority of patients experienced minimal detriments to their mental health, which is reassuring for clinicians and patients using medical cannabis. Moreover, there is a subset of patients that improved over time, although it is uncertain how clinically important this improvement is as overall effects were relatively small. Many of the patients were using antidepressants while also using medical cannabis, however SSRIs were the only class of antidepressant statistically associated with a change in PHQ-9 scores, however the clinical importance of this interaction remains unknown. Given wide variability of the type of cannabis products or cannabis cultivars used, we would expect that any PHQ-9 differences would be hard to identify, however based on this study we found that the method of cannabis use does not significantly predict a change in PHQ-9 score. Despite this variability, subgroups of individuals were identified for scores that showed both improvement and worsening of symptoms.

Current recommendations from Canadian clinicians [14] and The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine [15] concur that there is very limited to insufficient evidence for medical cannabis’ efficacy in improving depression-related outcomes. From the literature, previous studies [16,17,18,19, 29] specifically utilizing the PHQ-9 tool to measure depression levels in association with (medicinal or recreational) cannabis use have shown inconsistent results. Turna et al. (2019) was the sole study from Canada (British Columbia) and found that 64.9% of patients reported a rating of 4 out of 5 (very effective) in alleviating their depression symptoms [16]. Despite this, the study also stated that this improvement was not clinically important and may have been confounded by those experiencing cannabis-withdrawal associated symptoms. Sexton et al. (2016) also reported a 86% reduction in depression-related symptoms as a result of cannabis use [4]. Conversely, Bahorik et al. (2017) reported that cannabis use worsened depression and the majority of patients had less improvements in depression symptoms [19]. Likewise, the two studies by Feingold et al. (2017) [17] and (2018) [18] reported that depression levels were markedly higher in medical cannabis users– but this study only compared the results to opioid users, and not the general population. The majority of the remaining clinical studies [10, 13, 21, 25] utilized other validation tools to measure depression outcomes and grouped depression under a general category of other mental health outcomes. Despite the mixed results, there was common observation amongst the studies that any initial increases in depression levels may not necessarily have been as a direct result of medical cannabis use [23].

The present study provides an important bridge for some of these knowledge gaps regarding cannabis and mental health outcomes. Indeed, depression is a major reason cited [16] for seeking medical cannabis authorization, hence the study provides important insight to potential safety and benefits regarding current and prospective users of medical cannabis. With the recent legalization of nonmedical cannabis in Canada, it is reassuring to observe that the majority of patients in this study did not experience a worsening of depression symptoms. These findings help contribute to the knowledge base on current and potential population health impacts of cannabis use, while at the same time, providing future direction to the field of mental health around cannabis research.

This analysis is currently the largest Canadian population-based study of medical cannabis use that we are aware of, but it is not without limitations. First, it is an observational study and thus, potential spectrum bias has to be considered as our cohort of patients are those who individually sought medical cannabis for treatment. Second, even though depression screening via the PHQ-9 is considered best practice for all clinicians, follow-up scores were not available for a large proportion of our cohort. Third, likewise to most pharmacoepidemiological studies, there is no absolute method for determining whether the medical cannabis authorized was consumed as prescribed, and if patients elected to use alternative treatments for depression. Fourth, comparative analysis with the outcomes from other studies remain challenging as previous studies predominantly do not utilize the PHQ-9 questionnaire to measure depression-related outcomes. Finally, our study is limited by the lack of clinical details: frequency, strain, quantity, and onset/age of depression symptoms.

Conclusions

In all, we found no evidence of a therapeutic benefit associated to authorizing medical cannabis for patients seeking help with depression, depression-like conditions, disorders and related symptoms. Currently, there is very low evidence on medical cannabis and its effects on depression outcomes in both the short- and long-term. Future studies should focus on the parallel use of screening questionnaires to control for PHQ-9 sensitivity, ensure adherence to medical cannabis authorization, and whether the efficacy of cannabis to manage depression is comparable to first-line antidepressants. Lastly, future studies can further explore potential factors that may have attributed to the improvement in scores pre- and post- 3-6 month time period. Our findings contribute new evidence for clinicians on a large group of patients regarding the potential impact of medical cannabis for depression-related symptoms.

Availability of data and materials

The dissemination of data results to study participants and or patient organizations in this research project is not possible/applicable. The data from the study will not be shared as only the researchers authorized by Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) can have access to the data as per their policies.

Abbreviations

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale

- CAGE-AID:

-

CAGE Questionnaire Adapted to Include Drugs

- SSRI:

-

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- SNRI:

-

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

- TCA:

-

Tricyclic antidepressants

- NDRI:

-

Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- NaSSA:

-

Noradnergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants

- MAOI:

-

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

References

Nadia Montero-Oleas IA-R, Nuñez-González S, Viteri-García A, Simancas-Racines D. Therapeutic use of cannabis and cannabinoids: an evidence mapping and appraisal of systematic reviews. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(12):15.

Hajizadeh M. Legalizing and regulating marijuana in Canada: review of potential economic, social, and health impacts. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(8):453–6.

Lum HD, Arora K, Croker JA, Qualls SH, Schuchman M, Bobitt J, et al. Patterns of marijuana use and health impact: a survey among older Coloradans. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2019;5:2333721419843707.

Sexton M, Cuttler C, Finnell JS, Mischley LK. A cross-sectional survey of medical Cannabis users: patterns of use and perceived efficacy. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016;1(1):131–8.

Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1383–91.

Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, Barnes TR, Jones PB, Burke M, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):319–28.

Sznitman SR, Bretteville-Jensen AL. Public opinion and medical cannabis policies: examining the role of underlying beliefs and national medical cannabis policies. Harm Reduct J. 2015;12:46.

Hosseini S, Oremus M. The effect of age of initiation of Cannabis use on psychosis, depression, and anxiety among youth under 25 years. Can J Psychiatr. 2019;64(5):304–12.

Fischer B, Murphy Y, Kurdyak P, Goldner E, Rehm J. Medical marijuana programs - why might they matter for public health and why should we better understand their impacts? Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:53–6.

Taub S, Feingold D, Rehm J, Lev-Ran S. Patterns of cannabis use and clinical correlates among individuals with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;80:89–96.

Park JY, Wu LT. Prevalence, reasons, perceived effects, and correlates of medical marijuana use: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:1–13.

Lev-Ran S, Roerecke M, Le Foll B, George TP, McKenzie K, Rehm J. The association between cannabis use and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2014;44(4):797–810.

Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Exploring the association between cannabis use and depression. Addiction. 2003;98(11):1493–504.

Allan GM, Ramji J, Perry D, Ton J, Beahm NP, Crisp N, et al. Simplified guideline for prescribing medical cannabinoids in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(2):111–20.

The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids. The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. The National Academies Collection. Washington (DC): Reports funded by National Institutes of Health; 2017.

Turna J, Simpson W, Patterson B, Lucas P, Van Ameringen M. Cannabis use behaviors and prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in a cohort of Canadian medicinal cannabis users. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;111:134–9.

Feingold D, Rehm J, Lev-Ran S. Cannabis use and the course and outcome of major depressive disorder: a population based longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:225–34.

Feingold D, Brill S, Goor-Aryeh I, Delayahu Y, Lev-Ran S. The association between severity of depression and prescription opioid misuse among chronic pain patients with and without anxiety: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:293–302.

Bahorik AL, Leibowitz A, Sterling SA, Travis A, Weisner C, Satre DD. Patterns of marijuana use among psychiatry patients with depression and its impact on recovery. J Affect Disord. 2017;213:168–71.

Belendiuk KA, Baldini LL, Bonn-Miller MO. Narrative review of the safety and efficacy of marijuana for the treatment of commonly state-approved medical and psychiatric disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10:10.

Halladay JE, Boyle MH, Munn C, Jack SM, Georgiades K. Sex differences in the association between Cannabis use and suicidal ideation and attempts, depression, and psychological distress among Canadians. Can J Psychiatr. 2019;64(5):345–50.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Kosiba JD, Maisto SA, Ditre JW. Patient-reported use of medical cannabis for pain, anxiety, and depression symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2019;233:181–92.

Esmaeelzadeh S, Moraros J, Thorpe L, Bird Y. The association between depression, anxiety and substance use among Canadian post-secondary students. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:3241–51.

Smith JM, Mader J, Szeto ACH, Arria AM, Winters KC, Wilkes TCR. Cannabis use for medicinal purposes among Canadian university students. Can J Psychiatr. 2019;64(5):351–5.

Gobbi G, Atkin T, Zytynski T, Wang S, Askari S, Boruff J, et al. Association of Cannabis use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and Suicidality in young adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019.

Leadbeater BJ, Ames ME, Linden-Carmichael AN. Age-varying effects of cannabis use frequency and disorder on symptoms of psychosis, depression and anxiety in adolescents and adults. Addiction. 2019;114(2):278–93.

Stith SS, Vigil JM, Brockelman F, Keeling K, Hall B. Patient-reported symptom relief following medical Cannabis consumption. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:916.

Bahorik AL, Sterling SA, Campbell CI, Weisner C, Ramo D, Satre DD. Medical and non-medical marijuana use in depression: longitudinal associations with suicidal ideation, everyday functioning, and psychiatry service utilization. J Affect Disord. 2018;241:8–14.

Pedersen ER, Miles JN, Osilla KC, Ewing BA, Hunter SB, D'Amico EJ. The effects of mental health symptoms and marijuana expectancies on marijuana use and consequences among at-risk adolescents. J Drug Issues. 2015;45(2):151–65.

Hartrick CT, Kovan JP, Shapiro S. The numeric rating scale for clinical pain measurement: a ratio measure? Pain Pract. 2003;3(4):310–6.

Atkinson TM, Mendoza TR, Sit L, Passik S, Scher HI, Cleeland C, et al. The brief pain inventory and its “pain at its worst in the last 24 hours” item: clinical trial endpoint considerations. Pain Med. 2010;11(3):337–46.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Dickson-Fuhrman E, Daum G, Jaffe J, Jarvik L. Screening for drug and alcohol abuse among older adults using a modified version of the CAGE. Am J Addict. 2001;10(4):319–26.

Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–201.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Production of this study has been made possible through a CIHR Catalyst Grant for Cannabis Research in Urgent Priority Areas, funded by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction using Health Canada Cannabis Research Initiative funds (CCSA 163022). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of CCSA or its funders. The funders did not participate in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DTE, JRBD, JGH, EH designed the study and DTE and JRBD acquired the data. DTE and JMR analyzed the data. CL, JMR, and DTE drafted the manuscript. All other authors revised it critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. All authors are accountable for the work and integrity of the work. The corresponding author and guarantor accepts full responsibility of the work and/or conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish. DTE attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Production of this study has been made possible through a CIHR Catalyst Grant for Cannabis Research in Urgent Priority Areas, funded by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction using Health Canada Cannabis Research Initiative funds (CCSA 163022). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of CCSA or its funders. Informed written signed consent was provided by the patient at the time of first referral which allowed data to be collected and used for clinical and research purposes. All data was released as de-identified data to the researchers. Patients and the public were not involved in the design, conduct and reporting of this research project as it was not applicable to this project. This study is based in part on data provided by Canadian Cannabis Clinics and CanvasRx Inc. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the researchers and do not necessarily represent the views of Canadian Cannabis Clinics or Canvas Rx Inc., each of whom do not express any opinion in relation to this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JRBD is on the board of directors of Aurora Cannabis Inc., which is a for-profit, company licensed for the cultivation and sale of medical cannabis. JGH has worked as a paid advisor and speaker for Canadian Cannabis Clinics. JRBD, and JGH have a financial interest in Aurora Cannabis Inc. DTE and JRBD holds a Mitacs Grant with Aurora as a partner. Mitacs is a national, not-for-profit organization that works with universities, private companies, and both federal and provincial governments, to build partnerships and administer research funding that supports industrial and social innovation in Canada. DTE does not have any past or present financial interest in the companies involved. CL, JMR, and EH, have no conflicts of interest to declare. Moreover, the research funders and companies listed were not involved in any aspect of the design or write-up of the study and all analysis was performed independent from the funders and companies.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Keywords used to code the reason for seeking medical cannabis, method of cannabis use, and antidepressant usage.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Changes in PHQ-9 from initial to final follow-up for all patients with follow-up PHQ-9 scores and based on initial depression categorization (n = 5103).

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Multiple Linear Regression Results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Round, J.M., Lee, C., Hanlon, J.G. et al. Changes in patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) scores in adults with medical authorization for cannabis. BMC Public Health 20, 987 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09089-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09089-3