Abstract

Background

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) such as abuse, neglect or household adversity may have a range of serious negative impacts. There is a need to understand what interventions are effective to improve outcomes for people who have experienced ACEs.

Methods

Systematic review of systematic reviews. We searched 18 database sources from 2007 to 2018 for systematic reviews of effectiveness data on people who experienced ACEs aged 3–18, on any intervention and any outcome except incidence of ACEs. We included reviews with a summary quality score (AMSTAR) of 5.5 or above.

Results

Twenty-five reviews were included. Most reviews focus on psychological interventions and mental health outcomes. The strongest evidence is for cognitive-behavioural therapy for people exposed to abuse. For other interventions – including psychological therapies, parent training, and broader support interventions – the findings overall are inconclusive, although there are some positive results.

Conclusions

There are significant gaps in the evidence on interventions for ACEs. Most approaches focus on mitigating individual psychological harms, and do not address the social pathways which may mediate the negative impacts of ACEs. Many negative impacts of ACEs (e.g. on health behaviours, social relationships and life circumstances) have also not been widely addressed by intervention studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have been defined as stressful experiences occurring during childhood that directly impact on a child or affect the family environment in which they live. They include physical, sexual or emotional abuse, neglect, or household adversity as a result of domestic violence, imprisonment, substance abuse, parental mental health problems or family breakdown [1]. This definition was used by an influential CDC study in the 1990s; more recent work has extended the definition to include child neglect, parental bereavement, and children living in care [2]. The potential impacts of ACEs are physiological and behavioural, as well as psychological, and translate into poorer outcomes across a wide range of health domains [3, 4].

It is unclear what works to prevent or mitigate these negative consequences, or promote positive outcomes for those who have experienced ACEs. Previous reviews have looked at specific ACE populations but have not covered the whole spectrum of ACEs. The aim of this overview of systematic reviews was to provide a broad map of the evidence on the effectiveness of interventions for children and young people who have experienced ACEs, and identify gaps in the literature. It included systematic reviews including any effectiveness studies on any ACE-exposed population, and included all interventions and outcomes.

Methods

Due to the extent of the available literature, we employed a review-of-reviews method to provide a broad overview of the topic [5, 6]. We focused on recent, high-quality reviews to prioritise the most methodologically robust evidence. The review question was: What is known from systematic reviews about the effectiveness of interventions for children and young people (3–18 years) who have been exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)?

The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (registration CRD42018092192). EPPI-Reviewer 4 software was used to manage data. After initial ad hoc scoping searches, we searched 23 databases and other online resources that contain research literature in healthcare, mental health, social care, social science, education, child and adolescent development, and systematic reviews, as follows:

ASSIA (Proquest)

British Education Index (EBSCO)

British Nursing Index (EBSCO)

Child development and adolescent studies (EBSCO)

CINAHL Plus (EBSCO)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Cochrane Library)

Database of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE) (Cochrane Library)

EMBASE (OVID)

ERIC (EBSCO)

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (OVID)

IBSS (Proquest)

Medline (OVID)

PILOTS (Published International Literature On Traumatic Stress)

PsycINFO (OVID)

PUBMED/Medline

Social Policy and Practice (OVID) (this includes the NSPCC Child Protection Database)

Sociological Abstracts (Proquest)

Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science)

Bielefeld Academic Search Engine

Campbell Collaboration Library

Epistamonikas

NHS Evidence

Research in Practice

The search strategy combined terms for specific ACEs with terms for children and young people, and terms for a range of systematic review types (see Additional file 1). The search was designed and implemented by an information specialist in consultation with other members of the review team. The search was limited to reviews published since 2007; however, reviews included older primary studies. In addition, we searched for references from the NICE guideline on transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services (NG43) and on child abuse and neglect (NG76). Searches were carried out in March 2018.

We included systematic reviews of effectiveness data on people who experienced ACEs aged between 3 and 18 inclusive (adults who had experienced ACEs as children were also included); see Additional file 1 for details. We excluded younger children (0–2 years) as interventions focusing on this age group tend to focus on primary prevention or on psychological factors such as attachment, rather than on the impacts of ACEs. We included any outcomes measured on the person who experienced ACEs except the incidence of ACEs themselves (i.e. we did not look at the primary prevention of ACEs, or at outcomes for parents). We used the broad definition of ACEs employed by Allen and Donkin [2], with the further addition of homelessness as an important family-level stressor. We limited inclusion to reviews in English due to limited resource for translation (reviews including non-English-language primary studies were included). In more detail, the inclusion criteria were as follows:

- 1)

Is the reference a systematic review of primary studies?

Include any review of primary studies which reports some information on the search strategy and clearly defined inclusion criteria.

- 2)

Does the review report effectiveness data?

Exclude reviews of observational quantitative data or qualitative data only.

- 3)

Does the review include (an) ACE population(s)?

Include the following populations: sexual abuse; physical abuse; verbal or emotional abuse; neglect. Include household adversity, where a parent or guardian: is a victim of intimate partner violence; is in prison or on probation; has a mental health problem; abuses alcohol or drugs; is separated or divorced; or has died. Include children and young people living in care (in a care setting or elsewhere; include kinship care; exclude adopted children). Include homeless children or young people. Exclude reviews whose population partly overlap with our ACE criteria, and/or which is defined with broader terms such as ‘high risk’ or ‘trauma’, unless ≥ 70% of included studies include populations in the ACE criteria above, or there is a clearly presented subgroup analysis of a subset of the studies which meet these criteria.

- 4)

Does the review concern interventions aimed at people who have experienced ACEs?

- 5)

Does the review report outcomes for children or young people (aged 3–18 inclusive) who have experienced ACEs?

Include any outcome relating to the child or young person, except outcomes relating to the (re)occurrence or incidence of ACEs themselves (abuse, parental substance use, homelessness etc.). Exclude reviews only reporting on parent/carer outcomes and not child outcomes. Include outcomes measured on people aged > 18 years if they experienced ACEs at age 3–18. Include any follow-up period.

- 6)

Does the review report data from OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) member countries?

- 7)

Is the review report available in English?

Include reviews which include non-English-language primary studies, if the review itself is reported in English.

- 8)

Was the review published in 2007 or later?

- 9)

Is a full report of the review available?

Exclude reviews for which only a protocol or an abstract is available.

An initial sample of 10% of abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers and differences resolved by discussion; the remaining abstracts were screened by a single reviewer. All full-text references were screened by two reviewers independently and differences resolved by discussion.

The AMSTAR tool was used to assess review quality [7]. Quality assessment was conducted by one reviewer and checked in detail by a second. We translated the AMSTAR results into an overall score out of 11 (see Additional file 1) and applied a threshold of 5.5 or higher for inclusion in the synthesis.

A narrative synthesis was undertaken. We grouped the data according to intervention type and outcome (see below). We extracted findings where reporting allowed, and where there was evidence from at least 2 controlled studies for a given intervention and outcome domain. Where reviews conducted meta-analyses we extracted pooled effect sizes, and otherwise summarised the results in general terms as effective, ineffective or mixed. We extracted data on all outcomes for those experiencing ACEs (not for parents), except those relating to (re)occurrence or incidence of ACEs themselves. Where multiple outcomes were reported, we aggregated them into the following domains:

Mental health (e.g. anxiety, depression)

Behaviour (e.g. externalising behaviour, problem behaviour)

Social and relationship outcomes (e.g. social support).

Results

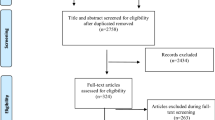

The flow of literature is shown in Fig. 1. Prior to quality assessment, 96 reviews were included. We included in the synthesis all reviews with an AMSTAR score of 5.5 or higher (N = 27). The full results of quality assessment are presented in Additional file 1. (Some reviews did not contribute to the synthesis, either because they were superseded by a later review [8] or contained no studies [9], or due to our restrictions on data extraction (see above) [10,11,12,13,14].)

The results are summarised in Table 1. We divided the findings into seven categories of intervention.

1. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. Seven reviews investigated CBT for a range of ACE populations [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The most substantive results come from Macdonald et al.’s review, which found that CBT improved mental health outcomes for people who had experienced abuse or neglect [19].

2. Other psychological therapies. A range of other psychological therapies, such as brief motivational interviewing, family therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy, were evaluated in six reviews [15, 18, 19, 21,22,23]. The findings do not provide strong evidence of effectiveness, although the interventions are heterogeneous.

3. Psychoeducation. Three reviews included psychoeducation [18, 19, 24]; the findings are mixed, although one meta-analysis finds evidence of effectiveness for mental health outcomes in children of parents with depression [24].

4. Parent / foster carer training. Eleven reviews included training for parents and foster carers, including a range of ACE populations; most studies focus on behaviour problems [17,18,19, 22, 23, 25,26,27,28,29,30]. However, the results overall are inconclusive.

5. Cross-sector support. Five reviews included cross-sector support interventions (such as case management, ‘wraparound’ support and treatment foster care), mainly for looked-after children and young people [18, 19, 23, 30, 31]. This category is heterogeneous and the results overall are mixed, but there are some positive findings.

6. Educational interventions. The evidence on educational and school-based interventions mainly comes from a single review on looked-after children and young people; the results overall are mixed [32].

7. Housing and life skills interventions. One review finds that support services for young people transitioning out of care are effective for housing and independent living outcomes but not for other outcomes [34], and one that interventions for homeless young people are largely ineffective for outcomes including alcohol or drug use or mental health [33].

Discussion

The findings of this review of reviews indicate that there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of most interventions for children and young people who have experienced ACEs. The strongest evidence is for the effectiveness of CBT for mental health outcomes in children who have been sexually abused. The evidence on other interventions and populations is generally more equivocal, although there are some positive findings.

Our findings indicate some important gaps in the review-level evidence. Most data relate to psychological interventions aiming to improve individuals’ mental resilience; this is true across the abuse and neglect populations as well as the household adversity populations. For the looked-after and homeless populations the range of interventions is somewhat broader, and includes more service-level programmes aiming to improve the support provided by agencies such as welfare services or schools. While the evidence on these interventions is inconclusive, it may be of value to explore their generalisability to other ACE populations. There is very limited evidence concerning any social or community-level interventions, for example to address socio-economic disadvantage or social isolation; this is not unexpected, as most such interventions include a broad range of populations and are unlikely to be evaluated on ACE populations specifically, but it is a limitation.

Similarly, the great majority of the outcomes measured in the studies relate to mental health or, for younger children, behaviour problems. With the exception of looked-after and homeless children and young people, there is very little data on broader outcomes in the domains of social relationships, life circumstances (e.g. housing, education) or behaviours (e.g. drug use, criminal involvement). As these outcomes have been identified in epidemiological research as important negative impacts of ACEs, the lack of effectiveness data on them is an important gap in the evidence.

The methodology used for this review has some limitations. It involves some double-counting of primary studies. In most cases the actual overlap between reviews is fairly limited and, given the high-level nature of the synthesis, unlikely to have a major impact on the interpretation of findings. The main exception is the literature on foster parent training, where three different reviews show substantial overlap [17, 23, 26]. The findings on this intervention should therefore be treated with caution. Our findings represent only a very high-level overview of the data: some of the intervention categories are very broad, and the ‘mixed’ results call for more detailed exploration. The findings are also partly dependent on review authors’ categorisation of interventions.

We defined ACEs in terms of a fixed list of population characteristics, partly for pragmatic reasons and partly because this approach has been widely used, and so facilitates comparison of our findings with the broader literature. However, it has some conceptual limitations. Many potentially relevant life stressors are not captured in ACE on our definition, including for example: factors affecting children and young people directly such as mental or physical health conditions, or alcohol or drug abuse; socioeconomic disadvantage and poverty, both at family level and community level; or broader environmental stressors such as community violence or natural disaster. The broader concept of ‘trauma’ covers some of these stressors [20, 35, 36], and could usefully be used to illuminate the broader dynamics of stress and resilience at work in ACE populations, although it arguably has limitations of its own. Conversely, treating ACEs as an itemised list of discrete experiences may not capture the role of multiple cumulative stress. Experiencing multiple ACEs is much more strongly correlated with negative outcomes than experiencing one or two [3, 37]. However, as our findings show, the effectiveness literature has tended to treat ACE populations separately, with limited consideration of the impacts of multiple interacting forms of disadvantage.

These limitations aside, this review suggests that the evidence base on interventions for people who have experienced ACEs may not be ideally suited to informing policy and practice. While individual interventions to mitigate psychological trauma are a potentially important avenue for addressing ACEs, many would argue that they need to form part of broader strategies which also aim to address the social factors which may mediate the negative impacts of ACEs, including material disadvantage and social isolation [2]. Such strategies could draw on interventions for the primary prevention of ACEs which were not included in this review [38, 39], but evidence on what works for people who have experienced ACEs is also needed. This could take the form of focused evaluation studies on, for example, school-based programmes or life skills training aiming to empower ACE populations, and/or subgroup analyses to understand how community-level interventions might address the consequences of ACEs. More indirect approaches could also be of value, such as modelling work using the epidemiological evidence base on the prevalence and distribution of ACEs to understand the likely impact of interventions with a broader population focus. Of course, such work should be based on consultation and involvement of children and young people who have experienced ACEs, to ensure it addresses their needs. It could also draw on the extensive body of qualitative evidence on these questions which points to the need for (evaluations of) longer term interventions which afford the necessary time to build up trust and address the ongoing and multi-faceted needs of children and young people affected by ACEs [40].

Conclusions

The evidence for most interventions for people who have experienced Adverse Childhood Experiences is equivocal; the most promising results are for CBT for mental health outcomes. The majority of the existing evidence focuses on psychological interventions and on mental health outcomes, and there is a lack of studies on service- or community-level interventions, and on social or behavioural outcomes. Evidence from observational and qualitative research indicates that people exposed to ACEs, especially multiple ACEs, often have complex needs, but there is limited information in the evaluation literature about how best to address these needs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACEs:

-

Adverse Childhood Experiences

- AMSTAR:

-

A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

References

Bellis MA, Ashton K, Hughes K, Ford K, Bishop J, Paranjothy S. Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on health-harming behaviours in the welsh adult population. Cardiff: Public Health Wales; 2015.

Allen M, Donkin A. The impact of adverse experiences in the home on the health of children and young people, and inequalities in prevalence and effects. London: UCL Institute of Health Equity; 2015.

Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Hardcastle KA, Perkins C, Lowey H. Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: a national survey. J Public Health. 2015;37:445–54.

Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:29–39.

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated March 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Thomson D, Russell K, Becker L, Klassen T, Hartling L. The evolution of a new publication type: steps and challenges of producing overviews of reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:198–211.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Macdonald G, Higgins JPT, Ramchandani P, Valentine JC, Bronger LP, Klein P, O'Daniel R, Pickering M, Rademaker B, Richardson G, Taylor M. Cognitive-behavioural interventions for children who have been sexually abused: a systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD001930.

Parker B, Turner W. Psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents who have been sexually abused. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD008162.

Bassuk EL, DeCandia CJ, Tsertsvadze A, Richard MK. The effectiveness of housing interventions and housing and service interventions on ending family homelessness: a systematic review. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:457–74.

Bee P, Bower P, Byford S, Churchill R, Calam R, Stallard P, Pryjmachuk S, Berzins K, Cary M, Wan M, Abel K. The clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of community-based interventions aimed at improving or maintaining quality of life in children of parents with serious mental illness: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 2014;18:1–250.

Broning S, Kumpfer K, Kruse K, Sack PM, Schaunig-Busch I, Ruths S, Moesgen D, Pflug E, Klein M, Thomasius R. Selective prevention programs for children from substance-affected families: a comprehensive systematic review. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:23.

Leenarts LE, Diehle J, Doreleijers TA, Jansma EP, Lindauer RJ. Evidence-based treatments for children with trauma-related psychopathology as a result of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22:269–83.

Naranbhai V, Abdool K, Meyer-Weitz A. Interventions to modify sexual risk behaviours for preventing HIV in homeless youth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1:CD007501.

Altena AM, Brilleslijper-Kater SN, Wolf JL. Effective interventions for homeless youth: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:637–45.

Beresford B, Clarke S, Gridley K, Parker G, Pitman R, Spiers G, Light K. Technical report for SCIE research review on access, acceptability and outcomes of services/interventions to support parents with mental health problems and their families. Social Policy Research Unit: York; 2008.

Fraser JG, Lloyd S, Murphy R, Crowson M, Zolotor AJ, Coker-Schwimmer E, Viswanathan M. A comparative effectiveness review of parenting and trauma-focused interventions for children exposed to maltreatment. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34:353–68.

Howarth E, Moore THM, Welton NJ, Lewis N, Stanley N, MacMillan H, Shaw A, Hester M, Bryden P, Feder G. IMPRoving outcomes for children exposed to domestic ViolencE (IMPROVE): an evidence synthesis. Public Health Res. 2016;4:1–342.

Macdonald G, Livingstone N, Hanratty J, McCartan C, Cotmore R, Cary M, Glaser D, Byford S, Welton NJ, Bosqui T, et al. The effectiveness, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for maltreated children and adolescents: an evidence synthesis. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20:1–508.

Wethington HR, Hahn RA, Fuqua-Whitley DS, Sipe TA, Crosby AE, Johnson RL, Liberman AM, Moscicki E, Price LN, Tuma FK, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to reduce psychological harm from traumatic events among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:287–313.

Wilen JS. A systematic review and network meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for adults who are sexually abused as children. PhD Thesis: Bryn Mawr: Bryn Mawr College; 2014.

British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health. Review of interventions to identify, prevent, reduce and respond to domestic violence. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2013.

Kinsey D, Schlosser A. Interventions in foster and kinship care: a systematic review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;18:429–63.

Loechner J, Starman K, Galuschka K, Tamm J, Schulte-Korne G, Rubel J, Platt B. Preventing depression in the offspring of parents with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;29:29.

Everson-Hock ES, Jones R, Guillaume L, Clapton J, Goyder E, Chilcott J, Payne N, Duenas A, Sheppard LM, Swann C. The effectiveness of training and support for carers and other professionals on the physical and emotional health and well-being of looked-after children and young people: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38:162–74.

Kemmis-Riggs J, Dickes A, McAloon J. Program components of psychosocial interventions in foster and kinship care: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2018;21:13–40.

Montgomery P, Gardner F, Ramchandani P, Bjornstad G. Systematic reviews of interventions following physical abuse: helping practitioners and expert witnesses improve the outcomes of child abuse. Oxford: Centre for Evidence-Based Intervention; 2009.

Troy V, McPherson Kerri E, Emslie C, Gilchrist E. The feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness, and effectiveness of parenting and family support programs delivered in the criminal justice system: a systematic review. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27:1732–1747.

Turner W, Macdonald G, Dennis JA. Behavioural and cognitive behavioural training interventions for assisting foster carers in the management of difficult behaviour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD003760.

Ziviani J, Feeney R, Cuskelly M, Meredith P, Hunt K. Effectiveness of support services for children and young people with challenging behaviours related to or secondary to disability, who are in out-of-home care: a systematic review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34:758–70.

Jones R, Everson-Hock ES, Guillaume L, Duenas A, Goyder E, Chilcott J, Payne N. The effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving access to health and mental health services for looked after children and young people. School of Health and Related Research: Sheffield; 2008.

Evans R, Brown R, Rees G, Smith P. Systematic review of educational interventions for looked-after children and young people: recommendations for intervention development and evaluation. Br Educ Res J. 2017;43:68–94.

Coren E, Hossain R, Pardo P, Bakker B. Interventions for promoting reintegration and reducing harmful behaviour and lifestyles in street-connected children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD009823.

Everson-Hock ES, Jones R, Guillaume L, Clapton J, Duenas A, Goyder E, Chilcott J, Cooke J, Payne N, Sheppard LM, Swann C. Supporting the transition of looked-after young people to independent living: a systematic review of interventions and adult outcomes. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37:767–79.

Cary CE, McMillen JC. The data behind the dissemination: a systematic review of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for use with children and youth. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34:748–57.

Gillies D, Maiocchi L, Bhandari AP, Taylor F, Gray C, O'Brien L. Psychological therapies for children and adolescents exposed to trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD012371.

Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, Jones L, Dunne MP. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e356–66.

Peacock S, Konrad S, Watson E, Nickel D, Muhajarine N. Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:17.

Selph SS, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Nelson HD. Behavioral interventions and counseling to prevent child abuse and neglect: a systematic review to update the U.S. preventive services task force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:179–90.

Lester S, Lorenc T, Sutcliffe K, Khatwa M, Stansfield C, Sowden A, Thomas J. What helps to support people affected by adverse childhood experiences? A review of evidence. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, University College London; 2019.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The report is based on independent research commissioned and funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme. The views expressed in the publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health, arms’ length bodies or other government departments. The funders had no role in designing the study, collecting, analysing or interpreting data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS wrote and conducted searches. SL and TL conducted screening, quality assessment and data extraction; SL, TL and KS conducted synthesis. TL wrote the first draft of the paper with the involvement of SL, KS and JT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Appendix A. Example search strategy. Appendix B. Quality assessment tool. Appendix C. Results of quality assessment. Appendix D. Quality assessment tools used in included reviews.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenc, T., Lester, S., Sutcliffe, K. et al. Interventions to support people exposed to adverse childhood experiences: systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health 20, 657 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08789-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08789-0