Abstract

Background

Community-driven projects that aim to address public concerns about health risks from H. pylori infection in Indigenous Arctic communities (estimated H. pylori prevalence = 64%) show frequent failure of treatment to eliminate the bacterium. Among project participants, treatment effectiveness is reduced by antibiotic resistance of infecting H. pylori strains, which in turn, is associated with frequent exposure to antibiotics used to treat other infections. This analysis compares antibiotic dispensation rates in Canadian Arctic communities to rates in urban and rural populations in Alberta, a southern Canadian province.

Methods

Project staff collected antibiotic exposure histories for 297 participants enrolled during 2007–2012 in Aklavik, Tuktoyaktuk, and Fort McPherson in the Northwest Territories, and Old Crow, Yukon. Medical chart reviews collected data on systemic antibiotic dispensations for the 5-year period before enrolment for each participant. Antibiotic dispensation data for urban Edmonton, Alberta (average population ~ 860,000) and rural northern Alberta (average population ~ 450,000) during 2010–2013 were obtained from the Alberta Government Interactive Health Data Application.

Results

Antibiotic dispensation rates, estimated as dispensations/person-years (95% confidence interval) were: in Arctic communities, 0.89 (0.84, 0.94); in Edmonton, 0.55 (0.55, 0.56); in rural northern Alberta, 0.63 (0.62, 0.63). Antibiotic dispensation rates were higher in women and older age groups in all regions. In all regions, the highest dispensation rates occurred for β-lactam and macrolide antibiotic classes.

Conclusions

These results show more frequent antibiotic dispensation in Arctic communities relative to an urban and rural southern Canadian population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are a major public health concern because they limit the effectiveness of therapeutic options available for the treatment of bacterial infections. Much evidence suggests that exposure to antibiotics leads to antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. In particular, consistent evidence shows an association between frequent exposure to antibiotics for the treatment of unrelated bacterial infections and the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Helicobacter pylori infection [1,2,3,4,5,6].

The Canadian North Helicobacter pylori (CANHelp) Working Group links northern Canadian communities, health care providers and regional health officials with University of Alberta investigators to conduct community-driven research aimed at addressing concerns about health risks from H. pylori infection; the ultimate goal is to inform public health policy pertaining to control of H. pylori infection [7]. In Canada, northern Indigenous communities are disproportionately burdened by H. pylori infection compared to multi-ethnic populations in southern Canada [8,9,10]. Available data show stomach cancer rates to be elevated in Indigenous Arctic populations as well, [11,12,13] an occurrence of great concern to affected communities and their health care providers.

H. pylori is a bacterium that colonizes the lining of the stomach and/or duodenum, [14] where it is nearly always accompanied by gastritis. This infection often persists indefinitely; in persistent cases, it increases the risk of peptic ulcer disease and stomach cancer [15,16,17,18]. Treatment to eliminate H. pylori infection has been observed to improve peptic ulcer healing, decrease peptic ulcer recurrence and reduce the risk of stomach cancer [19, 20]. Frequent treatment failure in populations with high prevalence of H. pylori infection is a major impediment to the development of effective H. pylori control strategies for such populations [21]. CANHelp community projects collected data on participants’ exposure to antibiotics as part of inquiry aimed at identifying causes of treatment failure.

Few studies have collected information on antibiotic exposure in geographically defined communities, even though it is known that the frequency of antibiotic use varies by geographic region, as well as other factors including age and sex [22,23,24]. Geographic differences in prescribing practices or non-prescription access to antibiotics likely contribute to differences in the occurrence of antibiotic-resistant infections across geographic regions [25, 26].

The aims of the current study are to describe antibiotic dispensation rates, as a measure of the frequency of overall exposure to systemic antibiotics, by community, sex, age and antibiotic class, in Canadian Arctic communities and compare these rates to those of urban and rural outpatient populations in the southern Canadian province of Alberta. These results will shed light on whether increased exposure to antibiotics is a potential explanation for reduced effectiveness of antibiotics in Indigenous Arctic populations, thus making them vulnerable to poor infection outcomes.

Methods

This analysis includes participants in community H. pylori projects conducted by the CANHelp Working Group in 4 hamlets in the western Arctic region of Canada: projects launched in Aklavik, Northwest Territories (NT) in 2007, Old Crow, Yukon (YT) in 2010, Tuktoyaktuk (NT) in 2011, and Fort McPherson (NT) in 2012 [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Each of these communities is predominantly Indigenous, mainly Gwich’in (Athabaskan First Nations) or Inuvialuit (western Canadian Inuit): Aklavik had 594 residents (2006 census), with 92% identifying as either Inuvialuit or Gwich’in; Old Crow had 245 residents (2011 census), with 90% identifying as Vuntut Gwitchin; Tuktoyaktuk had 854 residents (2011 census), with 92% identifying as Inuvialuit; and Fort McPherson had 792 residents (2011 census, with 94% identifying as Indigenous (mainly Gwich’in) [39, 40]. Each community project, guided by a planning committee comprising community leaders, included several components: surveys to collect risk factor data; non-invasive screening for H. pylori infection; endoscopy with gastric biopsy for pathological and microbiological assessment; treatment; and ongoing knowledge exchange activities. Diverse outreach strategies sought to encourage all community residents to participate. Project staff obtained informed consent from participants 17 years of age or older, parental consent for children under 17 years of age, and assent from 7 to 16-year-old participants.

The lead author (KW) collected chart review data for her MSc thesis research on factors associated with antibiotic-resistant H. pylori infection; [41] specifically, she collected antibiotic exposure history pertaining to CANHelp community project participants who fulfilled either or both of the following criteria for inclusion in this analysis: 1) available H. pylori isolates cultured from gastric biopsies and tested for antibiotic susceptibility; 2) completed treatment to eliminate H. pylori infection and were tested after treatment to assess post-treatment infection status. We collected each participant’s antibiotic exposure history from their medical chart, housed in community health centres, using a chart review tool to record systemic antibiotics prescribed for any reason during the 5 years before the participant’s enrolment date. This 5-year exposure period spanned different calendar years across communities because community projects were launched sequentially: our chart review recorded medications prescribed primarily during 2002–2007 in Aklavik, 2005–2010 in Old Crow, 2006–2011 in Tuktoyaktuk, and 2007–2012 in Fort McPherson (a few participants enrolled after the launch year, so their antibiotic exposure period began slightly later). Data collected from medical charts included: demographic factors; frequency of antibiotic prescriptions; types of antibiotics prescribed; and the reason for each prescription. An antibiotic prescription was defined as a single prescription of at least one systemic antibiotic regardless of the dose, dosing frequency or duration of the prescription.

As a measure of antibiotic use frequency, we estimated antibiotic dispensation rates, defining dispensation as the process by which a prescribed medication is given to a patient for whom a prescription was written. We used prescriptions as proxies for dispensations because medical charts noted prescriptions rather than dispensations, and because prescriptions given to patients at health centres in participating northern communities are dispensed routinely from locally stocked medication by health centre staff at the time of prescription; thus, in this study population, it can be assumed that each prescription noted in a medical chart was dispensed.

We expressed dispensation rates as the average of the number of antibiotic courses dispensed per person per year during each participant’s 5-year review period. We calculated these rates by dividing the total number of systemic antibiotic courses prescribed for all participants during the 5-year review period by the product of the number of participants and the sum of the number of years reviewed in the medical chart of each participant. We estimated antibiotic dispensation rates by community (Aklavik, Old Crow, Fort McPherson, Tuktoyaktuk), sex, age (categorized in 20-year age groups), and antibiotic class (β-lactams, macrolides, nitroimidazoles, nitrofurans, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, rifamycins).

To put the antibiotic dispensation rates observed in the western Arctic communities in perspective, we compared them to rates observed in Alberta, a western Canadian province located directly south of the Northwest Territories. We estimated antibiotic dispensation rates for the outpatient populations of urban Edmonton (Alberta’s capital) and rural northern Alberta using the online Alberta Government Interactive Health Data Application (IHDA), [42] which incorporates data from the following sources: the Pharmaceutical Information Network (PIN) database; the Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan Adjusted Mid-Year Population Registry Files; and the Alberta Health and Wellness Postal Code Translation File. The PIN captures all drug dispensation events occurring in community pharmacies across Alberta. Aggregate PIN data are available through the IHDA by geography, age group, sex, year, and antibiotic class. We restricted estimates of the Edmonton antibiotic dispensation rate to the population residing within the city limits (subzones Z4.1-Z4.4) and the rural northern Alberta rate to residents of the Alberta North Zone (subzones Z5.1-Z5.5); when we accessed data for both regions in March 2017, the only available data covered 2010 through 2013.

We estimated the outpatient antibiotic dispensation rates by dividing the number of antibiotic courses dispensed by the sum of the population during each year from 2010 through 2013. For statistical comparison, we used an estimation approach, presenting 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all estimated rates, rather than statistical significance testing, following best practice in statistical methods for epidemiology [43, 44]. To compare the Arctic community population to each of the two Alberta populations, we estimated rate differences and 95% CIs.

Results

We collected antibiotic exposure histories from medical charts of CANHelp community project participants: 164 from Aklavik; 67 from Old Crow; 52 from Fort McPherson; and 14 from Tuktoyaktuk. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the study population.

Among the 297 participants, the median number of systemic antibiotic prescriptions during the 5-year review period was 3 (IQR, 1–6; range, 0–38; mean, 4.3; SD, 4.6).

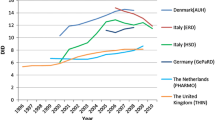

Table 2 presents estimated antibiotic dispensation rates in CANHelp community project participants and the outpatient populations of Edmonton and rural northern Alberta. The overall antibiotic dispensation rate was notably higher in the CANHelp community project study population (8.9 courses per 10 person-years) than in northern rural Alberta (6.3 courses per 10 person-years) or Edmonton (5.5 courses per 10 person-years). The estimated antibiotic dispensation rate in western Arctic communities was 3.3 (95% CI: 2.9, 3.8) courses per 10 person-years higher than the Edmonton outpatient population rate and 2.6 (95% CI: 21, 31) courses per 10 person-years higher than the rural northern Alberta outpatient rate.

Northern Alberta is a large geographic region with two small cities and vast sparsely populated areas. Table 3 presents estimated antibiotic dispensation rates for sub-zones of this region. Of note, the two cities have antibiotic dispensation rates slightly lower than Edmonton’s, while rates in the sparely populations zones range from 5.9 to 7.3 per 10 person-years, all substantially lower than the estimated rates in the Arctic communities.

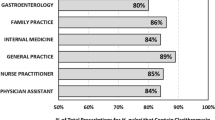

Table 4 presents estimated antibiotic dispensation rates for the Arctic communities and the outpatient populations of Edmonton and rural northern Alberta by sex, age and antibiotic class. Across all populations, the estimated dispensation rate was higher in woman than in men, the highest rates occurred in senior adults, and β-lactam antibiotics were dispensed at a substantially higher rate than other antibiotic classes. Stratification by age group and sex shows that dispensation rates were substantially higher in the Arctic communities within each age group and in both sexes. Of note, compared to the Alberta populations, dispensation rates in the Arctic communities were similar for β-lactams and macrolides, lower for fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines, higher for nitrofurans, and substantially higher for nitroimidazoles.

Discussion

Evidence from this study suggests that antibiotics are dispensed more frequently to western Arctic Canadians than to either urban or rural residents of the southwestern Canadian province of Alberta, independently of age and sex. This study showed additionally that antibiotics were dispensed more frequently to women relative to men and to the elderly relative to other age groups in each of the 3 settings investigated. Dispensation rates for the most frequently dispensed antibiotic classes, β-lactams and macrolides, was similar in the 3 populations, while fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines were dispensed less frequently and nitrofurans and nitroimidazoles were dispensed more frequently in the Arctic communities.

In the present study, the dispensation rate for systemic antibiotic prescriptions among participants in CANHelp Working Group community projects was 8.9 prescriptions per 10 person-years; an even higher antibiotic prescription rate of 15 per 10 person-years was estimated for an Alaska Native population in 2003 [2]. The urban antibiotic dispensation rates we estimated for Edmonton and the two small northern Alberta cities ranged from 5.2–5.5 per 10 person-years; a slightly lower antibiotic dispensation rate of 4.4 per 10 person-years was estimated from a 1992 study of United States physician practices [45]. More frequent use of antibiotics in rural and remote Arctic regions of North America relative to urban settings in this region is compatible with diverse explanations including higher incidence of infectious diseases, more limited access to diagnostic technology used to confirm bacterial infections leading to more frequent dispensation of antibiotics without a confirmed diagnosis, and different prescription practices resulting from more frequent provision of health care by nurses in phone consultation with physicians rather than by physicians directly [46, 47].

Variation in the use of antibiotics for the treatment of common bacterial infections may contribute to variation in antibiotic-resistant infection across geographic regions and sociodemographic groups [25, 26]. For example, the frequency of clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori infection has been reported to be higher in children than in adults, with evidence suggesting that this contrast is due to more frequent use of macrolide antibiotics in children for the treatment of respiratory tract infections [1, 48]. The frequency of metronidazole-resistant H. pylori infection has been reported to be higher in women than in men, [49] perhaps due to widespread use of nitroimidazole antibiotics for the treatment of gynaecological infections [2, 49,50,51,52,53,54]. For example, in a study conducted in the United Kingdom, nitroimidazole antibiotics were prescribed more frequently to women than to men, and the prevalence of metronidazole-resistant H. pylori infection was also higher in women relative to men [4]. Similarly, reports of higher prevalence of tetracycline-resistant H. pylori infection in women relative to men may be due to more frequent use of tetracycline in women for the treatment of urogenital infections [55]. Higher prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant H. pylori infection in women relative to men and in youth relative to adults may be associated with more frequent use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics for the treatment of urogenital and respiratory tract infections, respectively [55].

An important limitation of the present analysis is the potential underestimation of antibiotic use among participants in the Arctic Canadian community H. pylori projects. Participants’ medical charts only capture antibiotics dispensed at their community health centre. Many residents of the project communities spend time away from home and may receive health care in other locations. Most residents of northern Canadian communities, however, receive most of their health care at their community health centre; it is, therefore, likely that most antibiotics dispensed during the review period for this study were captured by our chart review. The data sources used for the Alberta populations would similarly miss prescriptions dispensed outside Alberta; however, given that Albertans are all entitled to health care provided by the provincial government, they are not likely to seek outpatient care for infections outside the province.

Another limitation pertains to our differential strategy for capturing dispensation events across territorial and provincial populations. In the northern communities included here, prescription events equate with dispensations. In Alberta, however, primary nonadherence is possible: an individual may be prescribed a drug but may not fill the prescription, precluding its dispensation [56, 57]. While this is unlikely to impact our ability to assess differences in dispensation patterns, it does limit our ability to investigate plausible explanations for results. Similarly, we were unable to assess whether a person who was dispensed an antibiotic used the medication as prescribed. As a result, we are restricted to reporting differences in potential exposure to antibiotics across these populations.

In this study, the time periods for which antibiotic dispensation rates were estimated differ in each of the Arctic communities (2002–2007, 2005–2010, 2006–2011, 2007–2012) due to the sequential conduct of these projects. These periods overlap to different degrees with the time period captured by the publicly accessible Alberta data, which was 2010–2013 at the time of data analysis. We would not, however, expect substantial changes in antibiotic dispensation during 2002 to 2013 based on studies of outpatient populations in Ontario, Canada and in the United States, which suggest that antibiotic dispensation rates remained relatively stable across age groups during this time period [58, 59].

Conclusions

This study reveals more frequent dispensation of antibiotics in Arctic Canada relative to urban and rural populations in southern Canada. These results suggest that increased exposure to antibiotics is a potential explanation for reduced effectiveness of antibiotics in Indigenous Arctic populations for treating infections such as H. pylori infection. More generally, Indigenous Arctic populations may be particularly vulnerable to antibiotic-resistant infections associated with frequent exposure to antibiotics. The evidence generated by this analysis will be useful for developing strategies aimed at reducing health disparities arising from inequitable health care in Indigenous Arctic populations relative to other North American populations.

Availability of data and materials

Antibiotic dispensation data collected from community project participants are not available through open access due to terms stipulated in community-university partnership agreements. Data requests are reviewed according to a process outlined in the Statement on Stewardship and Dissemination of Knowledge Generated Collaboratively in CANHelp Working Group Community Projects available at http://canhelpworkinggroup.ca/research-program/collaborative-partnerships/. To initiate the data request process, contact the corresponding author. The interactive health data application (IHDA) dataset analysed for the current study are available at the following url: www.ahw.gov.ab.ca/IHDA_Retrieval/.

Abbreviations

- CANHelp Working Group:

-

Canadian North Helicobacter pylori Working Group

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- H. pylori :

-

Helicobacter pylori

- IHDA:

-

Alberta Interactive Health Data Application

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- NT:

-

Northwest Territories

- PIN:

-

Pharmaceutical Information Network

- PPI:

-

Proton-pump inhibitor

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- YT:

-

Yukon Territory

References

Perez Aldana L, Kato M, Nakagawa S, Kawarasaki M, Nagasako T, Mizushima T, et al. The relationship between consumption of antimicrobial agents and the prevalence of primary helicobacter pylori resistance. Helicobacter. 2002;7:306–9.

McMahon BJ, Hennessy TW, Bensler JM, Bruden DL, Parkinson AJ, Morris JM, et al. The relationship among previous antimicrobial use, antimicrobial resistance, and treatment outcomes for helicobacter pylori infections. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:463–9.

Megraud F, Coenen S, Versporten A, Kist M, Lopez-Brea M, Hirschl AM, et al. Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe and its relationship to antibiotic consumption. Gut. 2013;62:34–42.

Banatvala N, Davies GR, Abdi Y, Clements L, Rampton DS, Hardie JM, et al. High prevalence of helicobacter pylori metronidazole resistance in migrants to East London: relation with previous nitroimidazole exposure and gastroduodenal disease. Gut. 1994;35:1562–6.

Poon SK, Lai CH, Chang CS, Lin WY, Chang YC, Wang HJ, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in helicobacter pylori isolates in Taiwan in relation to consumption of antimicrobial agents. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:162–5.

Carothers JJ, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, Bensler M, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, et al. The relationship between previous fluoroquinolone use and levofloxacin resistance in helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e5–8.

CANHelp Working Group. https://www.canhelpworkinggroup.ca.

Bernstein CN, McKeown I, Embil JM, Blanchard JF, Dawood M, Kabani A, et al. Seroprevalence of helicobacter pylori, incidence of gastric cancer, and peptic ulcer-associated hospitalizations in a Canadian Indian population. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:668–74.

McKeown I, Orr P, Macdonald S, Kabani A, Brown R, Coghlan G, et al. Helicobacter pylori in the Canadian arctic: seroprevalence and detection in community water samples. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1823–9.

Sinha SK, Martin B, Sargent M, McConnell JP, Bernstein CN. Age at acquisition of helicobacter pylori in a pediatric Canadian first nations population. Helicobacter. 2002;7:76–85.

Young TK, Kelly JJ, Friborg J, Soininen L, Wong KO. Cancer among circumpolar populations: an emerging public health concern. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v75.29787.

Simkin J, Woods R, Elliott C. Cancer mortality in Yukon 1999–2013: elevated mortality rates and a unique cancer profile. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2017;76. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2017.1324231.

Cancer in the Northwest Territories: 2001-2010. 2014. https://www.assembly.gov.nt.ca/sites/default/files/td_61-175.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov 2016.

Ford AC, Axon ATR. Epidemiology of helicobacter pylori infection and public health implications. Helicobacter. 2010;15(Suppl 1):1–6.

An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. The EUROGAST Study Group. Lancet Lond Engl. 1993;341:1359–62.

Correa P, Ruiz B, Hunter F. Clinical trials as etiologic research tools in helicobacter-associated gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:15–9.

Rugge M, Di Mario F, Cassaro M, Baffa R, Farinati F, Rubio J, et al. Pathology of the gastric antrum and body associated with helicobacter pylori infection in non-ulcerous patients: is the bacterium a promoter of intestinal metaplasia? Histopathol. 1993;22:9–15.

Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 1993;22:89–104.

Takenaka R, Okada H, Kato J, Makidono C, Hori S, Kawahara Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication reduced the incidence of gastric cancer, especially of the intestinal type. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:805–12.

Hosking SW, Ling TK, Chung SC, Yung MY, Cheng AF, Sung JJ, et al. Duodenal ulcer healing by eradication of helicobacter pylori without anti-acid treatment: randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 1994;343:508–10.

Buiatti E, Muñoz N, Vivas J, Cano E, Peraza S, Carillo E, et al. Difficulty in eradicating helicobacter pylori in a population at high risk for stomach cancer in Venezuela. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 1994;5:249–54.

Meyer JM, Silliman NP, Wang W, Siepman NY, Sugg JE, Morris D, et al. Risk factors for helicobacter pylori resistance in the United States: the surveillance of H. pylori antimicrobial resistance partnership (SHARP) study, 1993-1999. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:13–24.

Osato MS, Reddy R, Reddy SG, Penland RL, Malaty HM, Graham DY. Pattern of primary resistance of helicobacter pylori to metronidazole or clarithromycin in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1217–20.

Fraser AG, Moore L, Hackett M, Hollis B. Helicobacter pylori treatment and antibiotic susceptibility: results of a five-year audit. Aust NZ J Med. 1999;29:512–6.

Kato M, Yamaoka Y, Kim JJ, Reddy R, Asaka M, Kashima K, et al. Regional differences in metronidazole resistance and increasing clarithromycin resistance among helicobacter pylori isolates from Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2214–6.

Elviss NC, Owen RJ, Xerry J, Walker AM, Davies K. Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance patterns and genotypes in adult dyspeptic patients from a regional population in North Wales. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:435–40.

Cheung J, Goodman K, Munday R, Heavner K, Huntington J, Morse J, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in Canada’s arctic: searching for the solutions. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:912–6.

Carraher S, Chang HJ, Munday R, Goodman KJ, CANHelp Working Group. Helicobacter pylori incidence and re-infection in the Aklavik H. pylori Project. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72 ctg, 9713056.

Colquhoun A, Geary J, Goodman KJ. Challenges in conducting community-driven research created by differing ways of talking and thinking about science: a researcher’s perspective. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72.

Morse AL, Goodman KJ, Munday R, Chang HJ, Morse JW, Keelan M, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing sequential with triple therapy for helicobacter pylori in an aboriginal community in the Canadian North. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:701–6.

Lefebvre M, Chang HJ, Morse A, van Zanten SV, Goodman KJ, CANHelp Working Group. Adherence and barriers to H. pylori treatment in Arctic Canada. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72:22791.

Cheung J, Goodman KJ, Girgis S, Bailey R, Morse J, Fedorak RN, et al. Disease manifestations of helicobacter pylori infection in Arctic Canada: using epidemiology to address community concerns. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e003689.

Hastings EV, Yasui Y, Hanington P, Goodman KJ, CANHelp Working Group. Community-driven research on environmental sources of H. pylori infection in arctic Canada. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:606–17.

Kersulyte D, Bertoli MT, Tamma S, Keelan M, Munday R, Geary J, et al. Complete genome sequences of two helicobacter pylori strains from a Canadian Arctic aboriginal community. Genome Announc. 2015;3. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.00209-15.

Government of Northwest Territories. NWT Bureau of Statistics - Tuktoyaktuk. https://www.statsnwt.ca/community-data/infrastructure/Tuktoyaktuk.html. Accessed 27 Jan 2018.

Government of Northwest Territories. NWT Bureau of Statistics - Fort McPherson. https://www.statsnwt.ca/community-data/infrastructure/Fort_Mcpherson.html. Accessed 27 Jan 2018.

Government of Northwest Territories. NWT Bureau of Statistics - Aklavik. https://www.statsnwt.ca/community-data/infrastructure/aklavik.html. Accessed 27 Jan 2018.

Government of Yukon YB of S Executive Council Office. Yukon Socio-Economic Web Portal. http://sewp.gov.yk.ca/region?regionId=YK.OC. Accessed 27 Jan 2018.

Statistics Canada. 2006 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 94–581-XCB2006001. Statistics Canada. 2006. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/rel/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=94533&PRID=0&PTYPE=89103&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2006&THEME=81&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=. Accessed 10 Aug 2015.

Statistics Canada. 2011 National Household Survey, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-010-X2011016. 2011.

Williams KF. Investigating the effect of antibiotic exposure on the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant H. pylori infection and the incidence of anti-H. pylori treatment failure in northern Canadian communities. ERA; 2016. https://doi.org/10.7939/R3TQ5RK43.

Government of Alberta. Interactive Health Data Application. http://www.ahw.gov.ab.ca/IHDA_Retrieval/ihdaData.do. Accessed 17 Jul 2016.

Rothman K. Epidemiology. An introduction. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Rothman K, Lash T, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

McCaig LF, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial drug prescribing among office-based physicians in the United States. JAMA. 1995;273:214–9.

Parkinson AJ, Bruce MG, Zulz T. International circumpolar surveillance, an Arctic network for the surveillance of infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:18–24.

Calbo E, Alvarez-Rocha L, Gudiol F, Pasquau J. A review of the factors influencing antimicrobial prescribing. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2013;31(Suppl 4):12–5.

Agudo S, Perez-Perez G, Alarcon T, Lopez-Brea M. High prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant helicobacter pylori strains and risk factors associated with resistance in Madrid, Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3703–7.

Megraud F. H pylori antibiotic resistance: prevalence, importance, and advances in testing. Gut. 2004;53:1374–84.

Koivisto TT, Rautelin HI, Voutilainen ME, Niemela SE, Heikkinen M, Sipponen PI, et al. Primary helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin in the Finnish population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1009–17.

Nahar S, Mukhopadhyay AK, Khan R, Ahmad MM, Datta S, Chattopadhyay S, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of helicobacter pylori strains isolated in Bangladesh. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4856–8.

Zullo A, Perna F, Hassan C, Ricci C, Saracino I, Morini S, et al. Primary antibiotic resistance in helicobacter pylori strains isolated in northern and Central Italy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1429–34.

O’Connor A, Taneike I, Nami A, Fitzgerald N, Murphy P, Ryan B, et al. Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin in Ireland. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1123–7.

Kostamo P, Veijola L, Oksanen A, Sarna S, Rautelin H. Recent trends in primary antimicrobial resistance of helicobacter pylori in Finland. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:22–5.

Boyanova L, Ilieva J, Gergova G, Davidkov L, Spassova Z, Kamburov V, et al. Numerous risk factors for helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance revealed by extended anamnesis: a Bulgarian study. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(Pt 1):85–93.

Fischer MA, Stedman MR, Lii J, Vogeli C, Shrank WH, Brookhart MA, et al. Primary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:284–90.

Tamblyn R, Eguale T, Huang A, Winslade N, Doran P. The incidence and determinants of primary nonadherence with prescribed medication in primary care: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:441–50.

Tan C, Graves E, Lu H, Chen A, Li S, Schwartz KL, et al. A decade of outpatient antimicrobial use in older adults in Ontario: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2017;5:E878–85.

Lee GC, Reveles KR, Attridge RT, Lawson KA, Mansi IA, Lewis JS, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States: 2000 to 2010. BMC Med. 2014;12:96.

ACUNS/AUCEN: Association of Canadian Universities for Northern Studies. Ethical Principles. https://acuns.ca/why-we-exist/. Accessed 17 Feb 2018.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. 2014.

Williams K, Walker E, Munday R, Keelan M, Yasui Y, Goodman K, et al. Investigating antibiotic dispensation rates by age, gender and antibiotic class among participants of community H. pylori projects in Arctic Canada. Miami, FL, USA; 2016. https://epiresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Abstract-Book-Final-070416.pdf.

Acknowledgements

This research was previously presented as a poster presentation at the 2016 Epidemiology Congress of the Americas in Miami, Florida, USA [62].

Funding

This study was funded in full by grants from multiple government agencies: ArcticNet (RES0010178), Network of Centres of Excellence of Canada; the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP115031); Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (201201159); Northern Scientific Training Program, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (grant to K. Williams); and the University of Alberta (training grant to K. Williams). Preparation of this paper was funded in part by Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (201201159). None of these agencies had any role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

KW is the submission’s guarantor. KW designed the research study, performed the research, collected and analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. KG contributed to and supervised the research design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. RM contributed to the design of data collection methods in northern community health centres, assessment of data quality, and manuscript review. AC contributed to the design and analysis of Alberta data, assessment of data quality, and manuscript review. Other members of the CANHelp Working Group (www.canhelpworkinggroup.ca) contributed in numerous ways to the design and implementation of the community H. pylori projects. All authors read and approved the final version of this article, including the authorship list.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The CANHelp community projects maintain ethical approval from the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board and territorial research licenses through the Aurora Research Institute (NT) and the Yukon Scientists and Explorers Act, with approval from the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, the Aklavik Health Committee, the Hamlet of Aklavik council, the Aklavik Community Corporation (Inuvialuit governance), the Aklavik Gwich’in council, the Old Crow Vuntut Gwitchin government, and the Fort McPherson chief and council. Our research program adheres to the Ethical Principles for the Conduct of Research in the North of the Association of Canadian Universities for Northern Studies [60] as well as the standards elaborated in Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada, Chapter 9 of the 2014 Tri-Council Policy Statement on the Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans issued by the Canadian Secretariat on Responsible Conduct of Research [61]. Study staff obtained informed consent during in-person conversations, during which the staff read to participants study information sheets approved by the university ethics board, addressed participants’ questions, and secured signatures on consent forms approved by the university ethics board; staff obtained written parental consent for children under 17 years of age and written assent from children aged 7–16 years or deemed old enough to assent by their parents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, K., Colquhoun, A., Munday, R. et al. Antibiotic dispensation rates among participants in community-driven health research projects in Arctic Canada. BMC Public Health 19, 949 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7193-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7193-3