Abstract

Background

The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis is increasing worldwide. Obesity is an important modifiable risk factor for both the incidence and progression of knee osteoarthritis. Consequently, international guidelines recommend all patients with knee osteoarthritis who are overweight receive support to lose weight. However, few overweight patients with this condition receive care to support weight loss. Telephone-based interventions are one potential solution to provide scalable care to the many patients with knee osteoarthritis. The objective of this study is to evaluate, from a societal perspective, the cost-utility and cost-effectiveness of a telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle service for patients with knee osteoarthritis, who are overweight or obese.

Methods

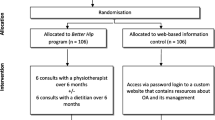

An economic evaluation was undertaken alongside a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Between May 19 and June 30, 2015, 120 patients with knee osteoarthritis were randomly assigned to an intervention or usual care control group in a 1:1 ratio. Participants in the intervention group received a referral to an existing non-disease specific 6-month telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle service. Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) was the utility measure and knee pain intensity, disability, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were the clinical measures of effect. Costs included intervention costs, healthcare utilisation costs (healthcare services and medication use) and absenteeism costs due to knee pain. Data was collected at baseline, 6 weeks and 26 weeks. The primary cost-effectiveness analysis was performed from the societal perspective.

Results

Mean cost differences between groups (intervention minus control) were $493 (95%CI: -3513 to 5363) for healthcare costs, $-32 (95%CI: -73 to 13) for medication costs, and $125 (95%CI: -151 to 486) for absenteeism costs. The total mean difference in societal costs was $1197 (95%CI: -2887 to 6106). For QALYs and all clinical measures of effect, the probability of the intervention being cost-effective compared with usual care was less than 0.36 at all willingness-to-pay values.

Conclusions

From a societal perspective, telephone-based weight loss support, provided using an existing non-disease specific 6-month weight management and healthy lifestyle service was not cost-effective in comparison with usual care for overweight and obese patients with knee osteoarthritis.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12615000490572, registered 18th May 2015

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis is one of the fastest growing chronic health problems worldwide [1, 2]. According to the 2015 Global Burden of Disease Study, osteoarthritis accounted for 3.9% of years lived with disability worldwide in 2015, up from 2.5% in 2010, and was the 13th highest contributor to global disability [1, 2]. Knee osteoarthritis consistently accounts for approximately 85% of the burden attributable to osteoarthritis [1, 2]. Osteoarthritis also imposes a significant economic burden, with the total annual costs estimated to be $A8.6 billion in Australia [3], £20.9 billion in the UK [4], and $US142.1 billion in the US [5]. The majority of these costs are attributable to ambulatory and inpatient care, including surgery and lost work productivity [3, 4].

Excess weight is an important modifiable risk factor for the onset and progression of knee osteoarthritis [6], and there is strong evidence that weight loss interventions reduce pain and disability in overweight patients with knee osteoarthritis [7, 8]. Consequently, international clinical practice guidelines recommend all patients with knee osteoarthritis who are overweight receive support to lose weight [9,10,11]. Typically, these treatments are delivered using clinical face-to-face models of care [12]. While such clinical models produce moderate effects on weight loss, pain, and physical function [7, 8], only 22% of patients with knee osteoarthritis referred for orthopaedic consultation at a large Australian public hospital report receiving weight loss care [13], possibly due to limitations in service delivery and patient access to care. Arguably more scalable delivery options, using remotely delivered approaches, such as telephone-based support, can maximise the reach of weight loss care and are more cost-effective to support weight loss in this patient group. While telephone-based behavioural interventions targeting weight loss are used routinely in the general populations, the cost-effectiveness of referring patients with knee osteoarthritis to these is unknown.

Given the scarce resources in healthcare, policy-makers are increasingly requiring evidence of economic value for healthcare interventions to make informed decisions about how to allocate resources [14]. Therefore, undertaking economic evaluations of knee osteoarthritis management approaches is important. Recently, we conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT) using an existing non-disease specific telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle service for patients with knee osteoarthritis who are overweight or obese [15]. The primary objective of the intervention was to reduce knee pain intensity, by reducing weight. The RCT found no between-group differences in knee pain intensity, nor weight [15]. Conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis is recommended in all trials, irrespective of their clinical effect [14]. This recommendation is based on cost-effectiveness analyses considering the joint distribution of differences in cost and clinical effect and thereby is able to show that an intervention is cost-effective when neither cost nor clinical effect differences are individually significant [14]. Cost-effectiveness analyses estimate the cost (saved or spent) per unit of effect gained. Such estimates can support healthcare policy and decision-makers choose which interventions should be implemented for specific health outcomes given the available resources [14]. The purpose of this study is to undertake an economic evaluation of the aforementioned RCT, compared to usual care.

Methods

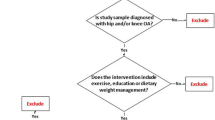

Study participants and design

The economic evaluation was conducted alongside a pragmatic parallel group RCT, which was part of cohort multiple RCT [16]. Full details of the study design has been described in the paper presenting the clinical results of the trial [15] and in the study protocol [17, 18]. The trial was prospectively registered (ACTRN12615000490572). The Hunter New England Health Human Research Ethics Committee (13/12/11/5.18) and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2015-0043) approved the RCT.

Patients on a waiting list for an outpatient orthopaedic consultation for their knee osteoarthritis at the John Hunter Hospital in NSW, Australia, were invited to participate. Patients were assessed for eligibility during a telephone assessment and eligible patients were randomised into either the intervention or usual care control group (1:1 ratio).

Inclusion criteria were: primary complaint of pain due to knee osteoarthritis lasting longer than 3 months; 18 years or older; overweight or obese (body mass index (BMI) ≥27 kg/m2 and < 40 kg/m2); average knee pain intensity ≥3 out of 10 on a 0–10 numeric rating scale (NRS) over the past week, or moderate level of interference in activities of daily living (adaptation of item 8 of SF36); and access to a telephone. Exclusion criteria were: known or suspected serious pathology as the underlying cause of their knee pain (e.g. fracture; cancer, inflammatory arthritis; gout; or infection); previous obesity surgery; currently participating in any prescribed or commercial weight loss program; knee surgery in the last 6 months or planned surgery in the next 6 months; unable to comply with the study protocol that requires them to adapt meals or exercise due to non-independent living arrangements; medical or physical impairment precluding safe participation in exercise such as uncontrolled hypertension; and unable to speak or read English sufficiently to complete study procedures. Recruitment for the trial occurred from May 19 to June 30, 2015, and follow-up concluded January 26, 2016.

Interventions

The intervention included two components. First, brief advice and education about the benefits of weight loss and physical activity for knee osteoarthritis were provided over the telephone immediately after randomisation. Second, intervention participants were informed about the NSW Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service (GHS) (www.gethealthynsw.com.au) [19], and referred to the service for weight loss support. The GHS is an existing government funded telephone-based health coaching service developed to support adults of the general population to make sustained healthy lifestyle improvements. Targets include diet, physical activity and achieving a healthy weight, and if suitable, referral to smoking cessation services [19]. The GHS provides 10 individually tailored coaching calls, centered on national dietary and physical activity guidelines [20, 21], delivered over a 6-month period by university qualified health professionals [19]. Participation in the intervention did not affect the patients’ place on the waiting list for orthopaedic consultation.

Participants in the control group remained on the ‘usual care pathway’ (i.e. on the waiting list to have an orthopaedic consultation and could progress to consultation if scheduled or surgery if recommended by the orthopaedic department) and took part in data collection during the 6-month intervention period. No other active intervention was provided as part of the study, however; no restrictions were placed upon the use of other health services. Control participants were informed that a face-to-face clinical appointment was available in 6 months with a study physiotherapist (CW).

Measures

All measures were collected by self-reported questionnaires at baseline, six weeks and 26 weeks (see Additional file 1: Appendix 1 for questionnaires). The baseline questionnaire was completed by telephone. Week 6 and week 26 surveys were completed via telephone or mailed in the post as per participant preference.

Utility measure

We measured utility using health-related quality of life, assessed using the 12-item Short Form Health Survey version 2 [22]. Participants’ SF-6D [23] health states were converted into utility scores using the British tariff [24]. QALYs were calculated by multiplying the duration of time spent in a health state by the participants’ utility score and were linearly interpolated between measurement points.

Clinical measures of effect

Primary outcome

Knee pain intensity was assessed using an 11-point NRS. Participants were asked to rate their “average knee pain intensity over the past week”, where 0 represents ‘no pain’ and 10 represents ‘the worst possible pain’ [25].

Secondary outcomes

Disability was assessed using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) [26]. The total WOMAC score ranges from 0 to 96, with higher scores indicating greater disability. Weight (kg) was assessed via participant self-report and BMI was calculated as weight/height squared (kg/m2) [27] using self-reported weight and height.

Cost measures

Costs were converted to Australian dollars in 2016 using the consumer price index [28]. As the follow-up of the trial was 26 weeks, discounting of costs was not necessary [29].

Intervention costs were estimated using a micro-costing approach and included the cost of delivering the telephone brief advice at baseline and the cost of the GHS coaching calls. The cost to deliver the brief advice was calculated by estimating the development and operational costs of the call and the estimated wages for the telephone interviewer to provide the brief advice (estimated average time 5 min). The cost to provide the GHS coaching calls was provided by the GHS [30] and multiplied by the number of calls each participant received. The GHS reported the number of health coaching calls participants received directly to the research team.

Healthcare utilisation costs were calculated from a patient reported healthcare utilisation inventory and included any healthcare services or medications used for knee pain (independent of the intervention costs). Participants were asked to recall the type of healthcare provided and the number of sessions attended as well as all medications used for their knee pain during the past six weeks, within the six and 26 weeks follow-up participant surveys. Healthcare services were priced according to Australian standard costs or professional organisations if this data was unavailable [31,32,33]. Medications were priced using unit costs from the Australian pharmaceutical benefits scheme [34] or online Australian pharmacy websites if this data was unavailable. To gain an estimate of the cost of healthcare utilisation over the entire 26-week period, the average of the week six and week 26 costs per patient was interpolated, assuming linearity.

Absenteeism was measured by participant recall of the total number of sickness absence days from paid work due to knee pain during the past six weeks, within the six and 26 weeks follow-up participant surveys. The ‘Human Capital Approach’ [29] was used to estimate absenteeism costs which involved multiplying each participant’s total number of sickness absence days off by the Australian Bureau of Statistic’s reported age and gender specific national average hourly income [27, 34]. To gain an estimate of the cost of absenteeism over the entire 26-week period, the average of the week six and week 26 costs per patient was interpolated, assuming linearity.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed in STATA (V13, Stata Corp). The sample size was based on the primary clinical measure of effect [15]. Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Descriptive statistics were used to compare baseline characteristics between the intervention and control group participants. Missing data for all effect and cost measures were imputed using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations [35]. The imputation model included variables related to the “missingness” of data and those that predicted outcome variables, imputations were stratified by treatment group. Variables in the model included baseline education level, employment status, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, age, country of origin, gender, and duration of knee pain. Ten different datasets were created (loss-of-efficiency < 5%) [35]. These separate datasets were analysed as indicated below, after which pooled estimates were calculated using Rubin’s rules [36].

Mean cost differences between study groups were calculated for total and disaggregated costs. The cost measures were adjusted for the confounders of baseline knee pain intensity, baseline duration of knee pain, baseline BMI and number of days on the waiting list for orthopaedic consultation because the addition of these confounders to the regression model changed the cost differences by more than 10%. Total cost (ΔC) and effect (ΔE) differences were estimated using seemingly unrelated regression analyses, adjusted for baseline values as well as other potential baseline prognostic factors (knee pain intensity, duration of knee pain, BMI and number of days on the waiting list for orthopaedic consultation, obtained from hospital records) [37]. Seemingly unrelated regression is advantageous because possible correlation between the two regression equations (i.e., one for ΔC and one ΔE) can be accounted for [37].

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated by dividing the adjusted difference in total costs between both groups by the difference in effects (i.e. ΔC/ΔE). Bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping (5000 replications) was used to estimate 95%CIs around cost differences and the uncertainty surrounding the ICERs. Uncertainty surrounding the ICERs was illustrated graphically using cost-effectiveness planes [29]. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, which consider the joint uncertainty of costs and effects, were used to graphically represent the intervention’s probability of cost-effectiveness in comparison with usual care at different values of willingness-to-pay [29].

The primary analysis was conducted from the societal perspective, which included all of the cost categories.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a per-protocol sensitivity analysis from the societal perspective that included only participants that completed at least six telephone GHS coaching calls in the intervention group (n = 20 participants).

Secondary analysis: Healthcare perspective

A secondary analysis was performed from the healthcare perspective, which excluded absenteeism costs.

Results

A total of 120 patients were randomised into the study (Fig. 1). Baseline participant characteristics were similar between groups (Table 1). Eleven participants in the intervention group and three in the control group were lost to follow-up. At 26 weeks, complete effect data was obtained from between 70 and 82% of participants (QALYs 70%, knee pain intensity 82%, disability 79%, weight 81%, BMI 81%). For cost data, complete data was obtained from 48% of participants at 26 weeks. As a consequence, between 18 and 30% of effect data and 52% of cost data were imputed.

Utility and clinical measures of effect

There were no differences found between groups for QALYs (Mean difference 0.00, 95%CI: -0.02 to 0.02), knee pain intensity (Mean difference 0.64, 95%CI: -0.49 to 1.77), disability (Mean difference 0.80, 95%CI: -6.68 to 8.47), weight (Mean difference − 0.02, 95%CI: -3.46 to 3.42), and BMI (Mean difference 0.11, 95%CI: -1.16 to 1.39) (Table 2).

Costs

The average number of GHS coaching calls to intervention participants was 4.7 (Standard deviation 4.6). The mean intervention costs were $622 (Standard error 80) per participant (Table 3). An overview of the unit costs and sources is reported in Table 4.

From the societal perspective, mean cost differences between groups (intervention minus control) were 493 (95%CI: -3513 to 5363) for healthcare costs, $-32 (95%CI: -73 to 13) for medication costs, and $125 (95%CI: -151 to 486) for absenteeism costs. The total mean difference in societal costs was $1197 (95%CI: -2887 to 6106) (Table 3). From the healthcare perspective, total mean difference between groups (intervention minus control) was $-1071 (95%CI: -5910 to 2931).

Societal perspective: Cost-utility

For QALYs, most of the incremental cost effect-pairs were located in the northwest quadrant (37.5%), indicating the intervention was on average more costly and less effective than usual care (Fig. 2 (1a)). The ICER for QALYs was 581,828 indicating that one QALY gained in the intervention group was associated with a societal cost of $581,828 as compared with the control group (Table 2). This large ICER is due to the large difference in cost (Mean difference 1197 (95%CI -2962 to 6139) and very small effect on QALYs (Mean difference 0.00, 95%CI: -0.02 to 0.02). The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for QALYs in Fig. 2 (2a) indicates the probability of the intervention being cost-effective in comparison to usual care was 0.36 at a willingness-to-pay of $0/unit of effect gained and the probability remained about the same irrespective of the willingness-to-pay.

Primary analysis (societal perspective): Cost-effectiveness planes indicating the uncertainty around the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (Fig. 2 (1)) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves indicating the probability of cost-effectiveness for different values ($) of willingness-to-pay per unit of effect gained from the societal perspective (Fig. 2 (2)) for QALY (a), pain intensity (b), disability (c), weight (d), and BMI (e) (based on the imputed dataset)

Societal perspective: Cost-effectiveness

For all clinical measures of effect, most of the incremental cost effectiveness-pairs were located in the northwest quadrant (Table 2, Fig. 2 (1b-1e)), indicating that the intervention on average achieved poorer outcomes at a higher cost compared to usual practice. Figure 2 (2b-2e) presents the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for knee pain intensity, disability, weight, and BMI.

For clinical measures of effect, the probability of the intervention being cost-effective in comparison to usual care was 0.35 at a willingness-to-pay of $0/unit of effect gained. For disability, weight, and BMI the probability remained about the same irrespective of the willingness-to-pay (Fig. 2 (2c-2e)). For knee pain intensity, this probability decreased with increasing values of willingness-to-pay (Fig. 2 (2b)).

Societal perspective: Sensitivity analysis

Results of the sensitivity analysis can be found in Table 2. In brief, for QALYs, the probability of cost-effectiveness was 0.63 at a willingness-to-pay of $0 per QALY gained (Fig. 3 (b)). For QALYs the probability of cost-effectiveness remained about the same irrespective of the willingness-to-pay.

Sensitivity analysis: Cost-effectiveness plane indicating the uncertainty around the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (a) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (b) indicating the probability of cost-effectiveness for different values ($) of willingness-to-pay per unit of effect gained for QALY

Healthcare perspective: Cost-utility

The ICER for QALY was 387,820 indicating that one QALY gained was associated with a cost of $387,820 compared with the control group (Table 2). The probability of the intervention being cost-effective in comparison to usual care was 0.40 at a willingness-to-pay of $0/unit of effect gained remained about the same irrespective of the willingness-to-pay (Fig. 4 (b)).

Secondary analysis (healthcare perspective): Cost-effectiveness planes indicating the uncertainty around the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (a) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (b) indicating the probability of cost-effectiveness for different values ($) of willingness-to-pay per unit of effect gained from the healthcare perspective for QALY

Discussion

We found that referral to a telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle service was not cost-effective from a societal perspective for patients with knee osteoarthritis who are overweight or obese, compared with usual care. The maximum probability of the intervention being cost-effective was low (≤0.40) for all outcomes for both the societal and healthcare perspectives, irrespective of the willingness-to-pay. The findings from the sensitivity analysis found the intervention had a slightly higher probability of cost-effectiveness compared to the main analysis, however the probability was still relatively low (i.e. 0.63 at a willingness-to-pay of $0/QALY) and remained the same regardless of willingness-to-pay.

To our knowledge, there are no other economic evaluations of telephone-based interventions for patients with knee osteoarthritis, hampering comparisons to similar interventions. A recent study assessed the cost-effectiveness of a 6-week multidisciplinary face-to-face treatment program compared with a telephone-based program for patients with osteoarthritis [38]. In this study, all patients received in-depth education about osteoarthritis, pain management, physical activity and diet, with the overall goal to enhance self-management skills [38]. Patients in the face-to-face group received six therapeutic groups session (2–4 h each), whereas the telephone group received only two face-to-face group sessions (2–2.5 h each) and four individual telephone contacts (15–30 min each). The study found that from a societal perspective the face-to-face treatment was more likely to be cost-effective when QALYs were the measure of benefit at 1-year follow-up [38]. Together with the findings from our current study, these results suggest that telephone-based care for patients with osteoarthritis may not be a cost-effective management approach. Since many patients with osteoarthritis do not receive recommended treatments via clinical models of care [13, 39], understanding why telephone-based interventions are reported to be as effective as face-to-face interventions but not cost-effective, is an important consideration to inform how best to provide care to this patient group.

An important strength of the present study is the pragmatic trial design, which enabled us to evaluate the intervention under ‘real world’ circumstances. This facilitates the generalisability of the results and allows decision-makers to use these results to help guide future healthcare interventions. A second strength is the use of contemporary statistical analysis methods. Multiple imputation was used to avoid loss of power due to sample size reduction and inefficiency associated with complete-case analyses and is regarded as a more valid way to deal with missing data than naïve imputation techniques, such as mean imputation or last observation carried forward [40]. Seemingly unrelated regression analyses were used for analysing the cost and effect components of the cost-effectiveness analysis. This method was used, instead of two separate regression analyses (i.e. one for costs and one for effects) or a net benefit framework, as it allowed us to adjust for various potential confounders that may not be the same for costs and effects, while simultaneously accounting for the possible correlations between costs and effects [37]. Bootstrapping techniques were used allowing for an estimation of the mean difference in costs as well as the joint uncertainty of costs and effects, while dealing with the right skewed nature of cost data.

This study is not without limitations. Firstly, the sample size calculation was based on the primary clinical measure of effect. While there have been a range of techniques proposed to estimate sample size based on economic endpoints [41,42,43], sample size calculations are usually performed based on the primary outcomes of the study [14, 44]. This is because cost data are right skewed and so require larger sample sizes than needed for trial outcomes to detect significant differences, which may not be feasible [14, 45]. Moreover, when performing a sample size calculation for economic endpoints a number of parameters need to be specified in advance e.g. cost measures, variance parameters of effectiveness measures, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, many of which are difficult to predict a priori [41,42,43]. As a result, economic evaluations conducted alongside clinical trials are typically underpowered [44] and should be interpreted with caution [45]. However, as economic evaluations are about estimation rather than formal hypothesis testing they still provide valuable information even when underpowered [29]. A second limitation is the rate of missing data at 26 weeks, between 18 and 30% for effect measures and 52% for cost data is high, however, not dissimilar to those in other economic evaluations [46]. Multiple imputation was used to account for the missing data, which is recommended over complete case analyses, still the results from this study should be treated with caution. Another limitation is that the self-reported cost data was interpolated to gain an estimate of costs over the 26-week intervention period as the recall period for participant’s healthcare utilisation and absenteeism was six weeks. Although it would be preferable for the recall period to cover the complete duration of follow-up we chose a shorter recall period to reduce participant recall bias. Lastly, presenteeism costs were not included, (i.e. reduced productivity while at work) which is known to be an issue reported by patients with chronic disabling pain [47].

There is a need for more information about the cost-effectiveness of lifestyle interventions for osteoarthritis. Although this study indicates that the use of a generic non-disease specific telephone-based service is not cost-effective for overweight and obese patients with knee osteoarthritis, the current evidence suggests existing models of care delivery are unable to provide recommended care to the large number of patients with knee osteoarthritis [13]. More research into how to provide scalable models of care that are cost-effective is needed. A potential way forward is to develop and test a range of scalable modes of weight loss care delivery e.g. telephone, online platforms (website, email), and mobile apps, and determine how these work together, or not, to deliver effective recommended care to patients. Importantly these various models of care delivery need to focus on delivering the same care e.g. focus on diet, exercise, to ensure that the studies are testing the mode of delivery, not the intervention components.

Interestingly, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis [9] refer to general obesity management guidelines for weight loss care for these patients [48], and not disease-specific models of care. Based on the results of our study, recommending general non-disease specific weight loss interventions may not be appropriate, or cost-effective for these patients. A key feature of our study and that of other osteoarthritis telephone interventions is that they only provide support over a relatively short period (six weeks to six months). However, other general weight loss programs occur over a much longer time frame. Better understanding about how the key ingredients for telephone services like dose and relevant components (e.g. exercise, weight loss, education) affect cost-effectiveness may provide more insight about the true value of telephone-based approaches for osteoarthritis.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that referral to a telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle service is not cost-effective compared with usual care for overweight and obese patients with knee osteoarthritis. These findings apply to QALYs, knee pain intensity, disability, weight, or BMI, from the societal and healthcare system perspectives.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- GHS:

-

Get healthy information and coaching service

- ICER:

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- QALYs:

-

Quality-adjusted life years

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

References

Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber R. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet Lond Engl. 2016;388(10053):1545–602.

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–96.

Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria. A problem worth solving: the rising cost of musculoskeletal conditions in Australia. Elsternwick: Arthritis and Osteoporosis Victoria; 2013.

Oxford Economics. The economic costs of arthritis for the UK economy. Oxford: Oxford Economics; 2010. Available from: https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/my-oxford/projects/128882

United States Bone and Joint Initiative. The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS), Third Edition [Internet]. Rosemont: United States Bone and Joint Initiative; 2014. [cited 2016 July 18]. Available from: Available at http://www.boneandjointburden.org

Silverwood V, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jinks C, Jordan JL, Protheroe J, Jordan KP. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil OARS Osteoarthr Res Soc. 2015;23(4):507–15.

Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):433–9.

Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, DeVita P, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(12):1263–73.

NICE. Osteoarthritis: care and management in adults. Clinical Guideline CG177 [Internet]. National Clinical Guideline Centre. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177/resources/osteoarthritis-care-and-management-pdf-35109757272517

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil OARS Osteoarthr Res Soc. 2014;22(3):363–88.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guideline for the non-surgical management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. 2009.

Shaw K, O’Rourke P, Del Mar C, Kenardy J. Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD003818.

Haskins R, Henderson JM, Bogduk N. Health professional consultation and use of conservative management strategies in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis awaiting orthopaedic consultation. Aust J Prim Health. 2014;20(3):305–10.

Petrou S, Gray A. Economic evaluation alongside randomised controlled trials: design, conduct, analysis, and reporting. BMJ. 2011;342:d1548.

O’Brien KM, Wiggers J, Williams A, Campbell E, Hodder RK, Wolfenden L, et al. Telephone-based weight loss support for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26(4):485–94.

Relton C, Torgerson D, O’Cathain A, Nicholl J. Rethinking pragmatic randomised controlled trials: introducing the “cohort multiple randomised controlled trial” design. BMJ. 2010;340:c1066.

O’Brien KM, Wiggers J, Williams A, Campbell E, Wolfenden L, Yoong S, et al. Randomised controlled trial of referral to a telephone-based weight management and healthy lifestyle programme for patients with knee osteoarthritis who are overweight or obese: a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010203.

O’Brien KM, Williams A, Wiggers J, Wolfenden L, Yoong S, Campbell E, et al. Effectiveness of a healthy lifestyle intervention for low back pain and osteoarthritis of the knee: protocol and statistical analysis plan for two randomised controlled trials. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(5):477–89.

O’Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, Venugopal K, Eakin EG, Eggins D, Caterson H, et al. Effectiveness of Australia’s get healthy information and coaching service®: translational research with population wide impact. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):292–8.

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC; 2013.

Brown W, Bauman A, Bull F, Burton N. Development of evidence-based physical activity recommendations for adults (18–64 years) Report prepared for the Australian Government Department of Health; 2012.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. In: Lincoln RI, editor. User’s manual for the SF-12v2 Health survey (with a supplement documenting SF-12 Health survey). Boston: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002.

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002 Mar;21(2):271–92.

Trépel D, Crean M, Begley E. Executive summary: an economic analysis of home care services for people with dementia. 2015 [cited 2017 Jan 20]; Available from: http://www.lenus.ie/hse/handle/10147/580006

Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short Form-36 bodily pain scale (SF-36 BPS), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(Suppl 11):S240–52.

Bellamy N. WOMAC user guide IX. Brisbane: QLD; 2009.

Heart N. Lung, and Blood Institute & North American Association for the study of obesity. The practical guide: identification, evaluation, and treatment for overweight and obesity in adults. Bethesda: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2000.

Reserve Bank of Australia. Inflation Calculator [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.rba.gov.au/calculator/annualDecimal.html

Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance G, O’Brien B, Stoddart G. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Scandol J, Phongsavan P, Haas M. An economic appraisal of the NSW get healthy information and coaching service. Sydney: Prevention Research Collaboration, Sydney School of Public Health; 2012.

AMA. List of Medical Services and Fees: 1 November 2016 [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Medical Association (AMA); 2016. Available from: https://ama.com.au/

Australian Government Department of Health. The July 2016 Medicare Benefits Schedule [Internet]. Australian Government Department of Health; [cited 2017 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.mbsonline.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Downloads-201607

NSW Health. Guideline: Costs of Care Standards 2009/10 [Internet]. NSW Health; Report No.: GL2011_007. 2011; Available from: https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ArchivePDSDocuments/GL2011_007.pdf

Australian Government Department of Health. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) | Home [Internet]. Australian Government Department of Health; [cited 2016 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home

White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–99.

Rubin DB. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. New York: Wiley; 1987.

Willan AR, Briggs AH, Hoch JS. Regression methods for covariate adjustment and subgroup analysis for non-censored cost-effectiveness data. Health Econ. 2004;13(5):461–75.

Cuperus N, van den Hout WB, Hoogeboom TJ, van den Hoogen FHJ, Vliet Vlieland TPM, van den Ende CHM. Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness analyses of face-to-face versus telephone-based nonpharmacologic multidisciplinary treatments for patients with generalized osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(4):502–10.

Hunter DJ, Neogi T, Hochberg MC. Quality of osteoarthritis management and the need for reform in the US. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(1):31–8.

Dziura JD, Post LA, Zhao Q, Fu Z, Peduzzi P. Strategies for dealing with missing data in clinical trials: from design to analysis. Yale J Biol Med. 2013;86(3):343–58.

Briggs AH, Gray AM. Power and sample size calculations for stochastic cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 1998;18(2 Suppl):S81–92.

Gardiner JC, Sirbu CM, Rahbar MH. Update on statistical power and sample size assessments for cost-effectiveness studies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2004;4(1):89–98.

Al MJ, van Hout BA, Michel BC, Rutten FF. Sample size calculation in economic evaluations. Health Econ. 1998;7(4):327–35.

Korthals-de Bos I, van Tulder M, van Dieten H, Bouter L. Economic evaluations and randomized trials in spinal disorders: principles and methods. Spine. 2004;29(4):442–8.

Briggs A. Economic evaluation and clinical trials: size matters. BMJ. 2000;321(7273):1362–3.

Noble SM, Hollingworth W, Tilling K. Missing data in trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis: the current state of play. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):187–200.

Agaliotis M, Mackey MG, Jan S, Fransen M. Burden of reduced work productivity among people with chronic knee pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(9):651–9.

NICE. Obesity: identification, assessment and management [internet]. National Clinical Guideline Centre. National Institute for Health and clinical excellence; 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by Hunter New England Local Health District, the University of Newcastle and the Hunter Medical Research Institute. The institutions had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KO, CW, AW, JW, RH and EC were responsible for the concept and design of the study. CW and JW were responsible for obtaining trial funding. KO, JVD and CW drafted the manuscript. KO, JVD, AW, SK, JW, RH, EC, ER, RH, CR, CM contributed to the interpretation of the data for the work and revision of the manuscript. KO, JVD, AW, SK, JW, RH, EC, ER, RH, CR, CM have read and approved the final manuscript. KO and CW take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to finished article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from The Hunter New England Health Human Research Ethics Committee (13/12/11/5.18) and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2015-0043) with verbal informed consent provided by all enrolled participants. Verbal consent was used due to the type of intervention used (i.e. telephone). The Hunter New England Health Human Research Ethics Committee and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee approved this procedure.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Appendix 1.Patient Questionnaire (Baseline) (DOCX 678 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Brien, K.M., van Dongen, J.M., Williams, A. et al. Economic evaluation of telephone-based weight loss support for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 18, 1408 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6300-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6300-1