Abstract

Background

Free VMMC services have been available in Uganda since 2010. However, uptake in Northern Uganda remains disproportionately low. We aimed to determine if this is due to men’s insufficient knowledge on VMMC, and if women’s knowledge on VMMC has any association with VMMC status of their male sexual partners.

Methods

In this cross sectional study, participants were asked their circumcision status (or that of their male sexual partner for female respondents) and presented with 14 questions on VMMC benefits, procedure, risk, and misconceptions. Chi square tests or fisher exact tests were used to compare circumcision prevalence among those who gave correct responses versus those who failed to and if p < 0.05, the comparison groups were balanced with propensity score weights in modified poisson models to estimate prevalence ratios, PR.

Results

A total of 396 men and 50 women were included in the analyses. Circumcision was 42% less prevalent among males who failed to reject the misconception that VMMC reduces sexual performance (PR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.38–0.89, p = 0.012), and less prevalent among male sexual partners of females who failed to reject the same misconception (PR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.07–0.76, p = 0.016). Circumcision was also 35% less prevalent among male respondents who failed to reject the misconception that VMMC increases a man’s desire for more sexual partners i.e. promiscuity (PR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.46–0.92, p = 0.014).

Conclusion

Misconceptions regarding change in sexual drive or performance were associated with circumcision status in this population, while knowledge of VMMC benefits, risks and procedure was not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

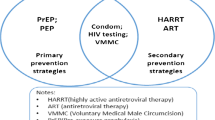

Three randomized trials demonstrated that Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision (VMMC) leads to a 50–60% relative risk reduction of female to male HIV transmission [1,2,3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNAIDS consequently recommended scale up of VMMC for HIV prevention settings as an additional important strategy for prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men [4]. Uganda in particular needs to circumcise 6.9 million men aged 10–49 by 2020 in order to halve HIV transmission compared to 2010. However, the annual number of circumcisions peaked in 2014, only 2.5 million men (59.5%) had been circumcised by 2016, and the initial regional disparities in circumcision levels persisted [5, 6]. In particular, some high HIV prevalence regions like Northern Uganda (7.2% HIV prevalence versus 6.2% national average) remain with disproportionately low circumcision levels [7].

In order to accelerate program progress, intensifying efforts such as targeted messaging to specific regions and age groups has been proposed [8, 9]. The Uganda National communication strategy for circumcision in HIV prevention specifies key messages to different target audiences [10]. The strategy guides communication to facilitate recruitment of eligible uncircumcised males in communities, and its used to develop Information Education & Communication /Behaviour Change Communication (IEC/BCC) materials which are simplified, illustrated, and translated to local languages to suit the setting. Although this strategy has been in effect since 2010 and free VMMC services are available, it is still unclear whether the low VMMC uptake in such settings is a knowledge problem. This study sought to determine the relationship between men’s knowledge on VMMC and their circumcision status, and if women’s knowledge on VMMC has any association with VMMC status of their male sexual partners.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in Gulu district in mid-northern Uganda. This region was the centre of a 20-year civil war, still has a high HIV prevalence above the national average (7.2 versus 6.2), and has a persistently low VMMC coverage [7]. Gulu district has an urban county (Gulu municipality) and two rural counties (Achwa and Omoro). VMMC services are available free-of-charge using funding from development partners, and are provided mostly through scheduled community outreaches, and also routinely at four health facilities - two in the urban county and two in the rural counties.

Study design and participants

In this cross-sectional study, we recruited consenting adults aged 18–49 years living in a household within Gulu district for more than 6 months by December 2015, and were within a 4 km radius from a health facility with free circumcision services. Men were the primary interest group, but women with male sexual partners were also included to determine if their knowledge had any association with circumcision status of their male sexual partners. Initially, service providers were included but were interviewed and found to have universal knowledge.

Study procedures

Systematic sampling was used to select households in each of the three counties of Gulu district (2 rural and 1 urban) using lists from a recent mosquito net distribution campaign. Eligible residents were ranked by age in descending order, and potential participants were randomly selected using a KISH grid [11]. These were then contacted for a possible interview, with two additional attempts for respondents who were not initially reached. A semi-structured questionnaire which was developed for this study (Additional file 1), was pre-tested at a non-study site, was used to collect cross-sectional data on sociodemographic characteristics, men’s circumcision status or circumcision status of the male sexual partner for female respondents (irrespective of whether the circumcision was medical or non-medical), and knowledge on VMMC. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, location, marital status, tribe, religion, education level, and occupation. The questions for knowledge on VMMC were selected from the National communication strategy [10], administered in a respondent’s preferred language, and included priority questions on VMMC benefits (n = 4 questions), risks (n = 1), procedure (n = 3), and misconceptions (n = 6). Misconceptions ought to be rejected, while facts on benefits, risks, and procedure ought to be accepted.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, and means(SD) and medians(IQR) were used for age. Correct acceptance of a fact or correct rejection of a misconception was scored 1, otherwise 0. Chi square tests or fisher exact tests were used to determine association between responses to each of the 14 selected/priority knowledge questions and circumcision status, the outcome of interest. For questions significantly associated with circumcision status, propensity score weighting (inverse probability of treatment weights) was then applied to balance those who gave correct responses and those who did not with respect to sociodemographic characteristics as potential confounders. Propensity scores were preferred over conventional regression modelling since they are much less vulnerable to model misspecification when dealing with measured confounders [12, 13] The balanced groups were then compared using modified poisson models to obtain prevalence ratios (PR), excluding subjects outside the common range of propensity scores. Prevalence Ratios (PR) were used because data were cross-sectional, they can convey strength of association between exposure and outcome, and are more conservative in magnitude than Prevalence Odds Ratios (POR) when the outcome is relatively common i.e. > 10% [14, 15], and have been used elsewhere in cross-sectional studies relating knowledge to circumcision [16, 17]. Modified poisson regression with robust variance can be used to estimate PR for cross-sectional data when log-binomial models fail to converge, which occurs quite often [15, 18]. To check potential influence of missing data on results, participants with missing responses to the selected knowledge questions were compared to those with complete responses using chi square tests or fisher exact tests as appropriate. Male and female respondents were analysed separately but results are presented side by side for comparison. STATA 14.2 was used for analysis [19].

Results

A total of 488 participants participated in the study; 428 were male and 60 were female. Circumcision prevalence was 30.6% among male respondents, and 26.7% among male sexual partners of female respondents. Complete response to all selected questions for VMMC knowledge was 92.5% (n = 396) among male respondents, and 83.3% (n = 50) among female respondents. We subsequently analysed respondents with complete responses, since those with incomplete responses were not different from those with complete responses with respect to sociodemographic characteristics and VMMC status, Additional file 2: Table S1.

Sociodemographic characteristics

The median age of male respondents was 25 years (IQR 22–29), and most were of the Acholi tribe (86.6%), 68.9% were catholic, and 72.7% had a secondary school education or higher. The Acholi tribe are a traditionally non-circumcising tribe. Location (rural or urban), tribe, education level, and occupation were associated with circumcision status of male respondents. In contrast, the median age of female respondents was 26.5 years (IQR 23–32), most were also of the Acholi tribe (84%), 64% were catholic, but less than half (46%) had a secondary school education or higher. Female respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics had no association with circumcision status of their male sexual partners, Table 1.

The association between men’s knowledge on VMMC and their circumcision status

Bivariate analyses (Table 2) showed that majority of men did not know that VMMC reduces cervical cancer risk for female partner (92.7% failed to accept), and most erroneously thought VMMC significantly reduces risk of HIV transmission to female partner (75.5% failed to reject). However, these were not associated with circumcision status (p > 0.05). Instead, the misconception that VMMC reduces sexual performance was strongly associated with circumcision status (p = 0.001). Also associated with circumcision status was knowledge whether men normally bleed after VMMC (p = 0.006), the misconception that men usually desire more sexual partners after VMMC i.e. that VMMC increases promiscuity (p = 0.016), and knowledge whether VMMC differs from traditional circumcision (p = 0.042).

After applying propensity weights in poisson models to balance the comparison groups (Additional file 3: Table S2), male respondents who failed to reject the misconception that VMMC reduces sexual performance had 42% lower prevalence of circumcision (PR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.38–0.89, p = 0.012). Also, men who failed to reject the misconception that VMMC increases a man’s desire for more sexual partners had 35% lower prevalence of circumcision (PR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.46–0.92, p = 0.014), Table 3.

Association between women’s knowledge on VMMC and the circumcision status of their male sexual partners

Bivariate analyses (Table 2) for female respondents showed that majority of female respondents (91.2%) did not know that VMMC reduces their risk for cervical cancer, and most (88.2%) also erroneously thought VMMC reduces their risk of HIV acquisition from male sexual partners. However, these were not associated with circumcision status (p > 0.05). Instead, the misconception that VMMC reduces a man’s sexual performance was significantly associated with circumcision status of their male sexual partners (p = 0.032). After applying propensity weights in poisson models, male sexual partners of female respondents who failed to reject misconception that VMMC reduces sexual performance had significantly lower prevalence of circumcision, although the estimate was imprecise (PR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.07–0.76, p = 0.016).

Discussion

It is interesting to note that knowledge of VMMC benefits, risk, and procedure was not associated with circumcision status of male respondents, or circumcision status of male sexual partners of female respondents. Instead, concern of reduced sexual performance was strongly associated with circumcision status of male respondents, as well as circumcision status of male sexual partners of female respondents. A qualitative study revealed similar concerns among Swazi men [20], but did not evaluate association with actual circumcision status and did not include female respondents. To date, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown no empirical evidence of reduced in sexual performance in circumcised men [21,22,23,24]. Similarly, the misconception that men desire more sexual partners after VMMC i.e. become more promiscuous was also independently associated with circumcision status of male respondents. This is probably a moral or religious concern, also with no empirical evidence to date [21, 23, 24]. These misconceptions regarding changes in sexuality following VMMC need to be effectively addressed in these communities, perhaps using novel approaches different from those in current use, and the novel approaches should ideally include female sexual partners whenever applicable and possible.

Limitations

We could not establish whether the knowledge preceded circumcision given the cross-sectional design i.e. temporality between exposure and outcome, but the observed associations could plausibly explain the reluctance of men in this setting to get circumcised, and the reluctance of women to encourage their male sexual partners. Unmeasured confounders may explain away the observed association, but sensitivity analyses for these would also involve more untestable assumptions. Subsequent studies could establish temporality between messaging and subsequent circumcision; and also explore exposure to specific VMMC messages especially those addressing misconceptions and relationship with actual knowledge or attitudes to check whether messages are truly effective or not. A qualitative study in the same setting could complement our findings by further exploring cultural influences and other attitudes.

Conclusion

Misconceptions regarding change in sexual drive or performance were associated with VMMC status in this population, while knowledge of VMMC benefits, risks and procedure was not.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immunodeficiency syndrome

- BCC:

-

Behavioral Communication Change

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency Syndrome

- IEC:

-

Information Education and Communication

- UNAIDS:

-

United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS

- VMMC:

-

Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–66 doi: S0140-6736(07)60313-4 [pii].

Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2(11):e298 doi: 05-PLME-RA-0310R1 [pii].

Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–56. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(07)60312-2/fulltext. Accessed Apr 23, 2017.

WHO/UNAIDS Technical Consultation : Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention : Research Implications for Policy and Programming (2007 : Montreux, Switzerland), World Health Organization, UNAIDS. New data on male circumcision and HIV prevention : Policy and programme implications : WHO/UNAIDS technical consultation male circumcision and HIV prevention : Research implications for policy and programming, montreux, 6–8 march 2007 : Conclusions and recommendations . 2007.

Uganda AIDS Commission. The uganda HIV and AIDS country progress report; july 2015-june 2016. Uganda Ministry of Health. 2016;25:S1–58.

Uganda Ministry of Health, ICF International. 2011 uganda AIDS indicator survey: Key findings. . 2012. http://health.go.ug/docs/UAIS_2011_KEY_FINDINGS.pdf.

Uganda AIDS commission. Uganda population based HIV impact assessment report 2017, vol. 2; 2017.

Kripke K, Vazzano A, Kirungi W, et al. Modeling the impact of uganda's safe male circumcision program: implications for age and regional targeting. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158693. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158693.

Katharine Kripke, Marjorie Opuni, Melissa Schnure, et al. Age targeting of voluntary medical male circumcision programs using the decision makers' program planning toolkit (DMPPT) 2.0. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0156909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156909.

Uganda Ministry of Health. Safe male circumcision for HIV prevention: National communication strategy. Uganda: Uganda Ministry of Health; 2010. p. 7–10.

McBurney P. On transferring statistical techniques across cultures: the Kish grid. Curr Anthropol. 1988;29(2):323–5. https://doi.org/10.1086/203642.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. . 1983. http://www.stat.cmu.edu/~ryantibs/journalclub/rosenbaum_1983.pdf.

Kuss O, Blettner M, Börgermann J. Propensity score: an alternative method of analyzing treatment effects. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2016;113(35–36):597. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2016.0597.

Behrens T, Taeger D, Wellmann J, et al. Different methods to calculate effect estimates in cross-sectional studies a comparison between prevalence odds ratio and prevalence ratio. Methods Inf Med. 2004;43(5):505–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15702210.

Bastos LS, de Vasconcellos OR, de Velasque LdS C. Obtaining adjusted prevalence ratios from logistic regression models in cross-sectional studies. Cadernos de saude publica. 2015;31(3):487–95. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00175413.

Michelle R Kaufman, Eshan U Patel, Kim H Dam, et al. Impact of counseling received by adolescents undergoing voluntary medical male circumcision on knowledge and sexual intentions. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;66(suppl_3):S228. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix973.

Lynn M Van Lith, Elizabeth C Mallalieu, Eshan U Patel, et al. Perceived quality of in-service communication and counseling among adolescents undergoing voluntary medical male circumcision. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;66(suppl_3):S212. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix971.

Williamson T, Eliasziw M, Fick GH. Log-binomial models: Exploring failed convergence. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2013;10(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-7622-10-14.

StataCorp. Stata: Release 14. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. 2015.

Adams A, Moyer E. Sex is never the same: Men's perspectives on refusing circumcision from an in-depth qualitative study in Kwaluseni, Swaziland. Global Public Health. 2015;10(5–6):721–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1004356.

Morris BJ, Krieger JN. Does male circumcision affect sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction?—a systematic review. J Sex Med. 2013;10(11):2644–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12293.

Y Yang, X Wang, Y Bai, P Han. Circumcision does not have effect on premature ejaculation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrologia (Online). 2018;50(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/and.12851.

Shabanzadeh DM, Düring S, Frimodt-Møller C. Male circumcision does not result in inferior perceived male sexual function - a systematic review. Danish medical journal. 2016;63(7). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27399981.

Wei Liu Jian-Zhong Wang Romel Wazir Xuan Yue Kun-Jie Wang. Effects of circumcision on male sexual functions: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2013;15(5):662–666. https://doi.org/10.1038/aja.2013.47.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my supervisors both at Makerere School of Public Health and the Uganda Ministry of Health, the research assistants and the study community.

Funding

This work was supported by a Fogarty grant through the Rakai Health Science Program, the African Population and Health Research Centre, and personal resources from the corresponding author.

Availability of data and materials

The “Knowledge on Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision in a low uptake setting in Northern Uganda” data that support the findings of this study are available in/from “mendeley”, “https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/6y6k26b9kb/draft?a=4977130b-1f12-42a6-b917-763462f8d8a9”. Names have been removed from the dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BMN: Developed the concept, conducted the study, analyzed the data, prepared the manuscript, addressing of reviewer comments; DS: Supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript; ENK: Contributed to analysis and addressing of reviewer comments; GBM: Contributed to analysis and addressing of reviewer comments; RG: Supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript; FEM: Contributed to study design, supervised the study, contributed to analysis and addressing of reviewer comments. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Makerere University School of Public Health institutional review board (IRB Number HS 1923), and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST). All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

All participants provided informed and written consent for publication of the results.

Competing interests

Dr. Barbara Marjorie Nanteza is the National Safe male circumcision coordinator at the Uganda Ministry of Health. Other co-authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Questionnaire used to assess knowledge on HIV and VMMC in a low uptake setting in Northern Uganda. This questionnaire was developed from the Uganda National communication strategy for circumcision in HIV prevention. We prioritized questions on VMMC benefits (n = 4 [qn18, qn20, qn22, qn23]), risks (n = 1 [qn25]), procedure (n = 3 [qn7, qn11, qn14]), and misconceptions (n = 6 [qn16, qn17, qn21, qn24, qn34, qn36]). Socio-demographics and priority questions used for this paper are marked with an asterisk (*) in supplement 3. (DOC 129 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Comparison of participants with complete responses versus those with incomplete responses to knowledge questions on VMMC. (DOC 45 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S2. Balancing of comparison groups with propensity score weights. Numbers are Standardized mean differences (SMD), and an absolute SMD < 0.1 is desirable for each observed covariate. Only questions with p < 0.05 in bivariate analyses (Table 1) are included. (DOC 50 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nanteza, B.M., Serwadda, D., Kankaka, E.N. et al. Knowledge on voluntary medical male circumcision in a low uptake setting in northern Uganda. BMC Public Health 18, 1278 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6158-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6158-2