Abstract

Background

Singapore remains vulnerable to worldwide epidemics due to high air traffic with other countries This study aims to measure the public’s awareness of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Avian Influenza A (H7N9), identify population groups who are uninformed or misinformed about the diseases, understand their choice of outbreak information source, and assess the effectiveness of communication channels in Singapore.

Methods

A cross-sectional study, comprising of face-to-face interviews, was conducted between June and December 2013 to assess the public’s awareness and knowledge of MERS and H7N9, including their choice of information source. Respondents were randomly selected and recruited from 3 existing cohort studies. An opportunistic sampling approach was also used to recruit new participants or members in the same household through referrals from existing participants.

Results

Out of 2969 participants, 53.2% and 79.4% were not aware of H7N9 and MERS respectively. Participants who were older and better educated were most likely to hear about the diseases. The mean total knowledge score was 9.2 (S.D ± 2.3) out of 20, and 5.9 (S.D ± 1.2) out of 10 for H7N9 and MERS respectively. Participants who were Chinese, more educated and older had better knowledge of the diseases. Television and radio were the primary sources of outbreak information regardless of socio-demographic factors.

Conclusion

Heightening education of infectious outbreaks through appropriate media to the young and less educated could increase awareness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Following the global influenza pandemic caused by the novel influenza A virus in 2009 (H1N1–2009), the world continues to be threatened by emerging respiratory diseases such as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2012 and Avian Influenza A (H7N9) in 2013 [1, 2]. The onset of MERS and H7N9 infections in humans are typically characterized by high fever (≥ 38 °C) and cough, and can lead to progressive pneumonia, respiratory failure and death, contributing to case fatality rates of 35% and 19% respectively at the time when this study was performed [2,3,4].

Such infectious diseases are of concern due to global travel and high volumes of air traffic. Since the first reported case in China, imported cases of H7N9 have been observed in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Canada and Malaysia [5,6,7]. While human-to-human transmission is limited [8], Singapore remains vulnerable to imported cases of H7N9 due to high air traffic between China and Singapore. In the first half of 2014, Singapore received close to a million tourists from China [9], while China ranks as the third most frequent outbound travel destination among Singaporeans [10]. Similarly, despite the fact that most MERS cases have been reported in the Arabian Peninsula and sustained community transmission has not been documented, imported cases have occurred in the region including in Malaysia, Thailand and the Republic of Korea [11]. Although both H7N9 and MERS were not epidemic at the time of the study and knowledge available on both diseases were limited to global news and reports, given Singapore’s position as an international trading and traveling hub, it is still important to convey to the public accurate and timely information on the nature of the infectious outbreak, its transmission modes and preventive measures so as to better prepare them for potential epidemics.

The International Health Regulations (2005) states risk communication as one of the eight core capacities for outbreak preparedness [12]. For the planning of effective risk communication, it is necessary to assess the public’s knowledge level to determine vulnerable target groups. Multiple cross-sectional studies have been done to assess knowledge and attitude of the public on past respiratory disease outbreaks [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Ethnicity, age and education level were found to influence an individual’s knowledge level of infectious outbreaks. These studies strongly indicate the need to consider audience segmentation along with appropriate use of media channels, allowing for tailored public health messages to be delivered timely and accurately [19, 20].

Understanding how the public gathers information on infectious diseases, and what media channels are preferred to deliver customized messages before an outbreak, equips the government with useful information for risk communication planning [21, 22]. Credible and timely message delivery through appropriate media channels is necessary to ensure the public gets accurate information on emerging infectious diseases to make informed decisions on protective health behaviors [23, 24]. Studies have also shown that inconsistent and untargeted risk communication messages may result in gaps in health-related knowledge and eventually, health outcomes [25,26,27].

The objective of this study is to identify the groups most likely to be uninformed or misinformed about H7N9 and MERS infection, as well as to determine appropriate media channels for public health education in Singapore. It also aims to assess if the public are given sufficient information to take specific preventive measures to protect themselves. Findings from the study will help health promotion agencies develop effective communication strategies to mitigate the risk of future emerging infectious agents.

Methods

Sample

A cross-sectional community-based survey was carried out in Singapore, a densely-populated (7987 people/km2) tropical island city-state with a total population of 5.61 million [28], from June to December 2013. The participants were recruited from 3 existing studies: 1) Singapore Health 2012 [29], 2) Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health (SSHSPH) Revisit of the Multi-ethnic and Diabetic Cohorts [30] and 3) Revisiting the Singapore Consortium of Cohort Studies – Multi-ethnic cohort. Respondents were randomly selected and contacted via phone to explain the nature of the study and invited to participate. In addition, an opportunistic sampling approach was also used to recruit new participants or members in the same household through referrals from existing participants.

Although the main aim of the study was to determine the adequacy of public health communications on H7N9 and MERS in Singapore, it was also planned that in the event of a community outbreak, the study population will allow us to establish the attack rate of either virus through a sero-epidemiological investigation. Hence, assuming a true proportion of 10% and at 95% confidence, a sample size of 3000 (500 participants under 21 years, 2000 participants between 21 and 55 years and 500 participants above 55 years) was calculated to allow for sufficient power to estimate the proportion of population infected with either disease to a precision of 2.6% for the young and old and 1.3% for those aged between 21 and 55 years. The calculated sample size was also deemed sufficient for the questionnaire.

Instrument

The paper-based questionnaire was adapted from a literature review of published articles on knowledge of H1N1 and H5N1 [31,32,33], as well as existing questions from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. The Health Belief Model was also employed so as to include questions on perceived susceptibility, severity and benefits and cues to action [34]. A small pilot test was conducted among staff of the SSHSPH to fine-tune the questionnaire such that it is adapted to the local culture and language. Demographic questions relating to gender, age group, ethnicity, housing type (as more than 80% of the local residents live in public housing [35], further stratification between public and private housing could provide insights to the socio-economic status of our study population) and education level were asked before the survey started. A 15–20 min face-to-face survey was conducted by a team of trained multi-ethnic interviewers at the participant’s home or a place of their choice. The questionnaires were conducted in one of the four official languages of Singapore, based on the participant’s preference: English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil.

Participants were asked if they have ever heard of H7N9 and/or MERS and their preferred information source about infectious disease outbreaks, with traditional media channels, social media and word of mouth from family, friends and colleagues as possible options. Participants could choose more than one preferred information source. For the knowledge assessment of H7N9, participants were asked to answer ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘not sure’ on two sections, namely the scientific understanding and transmission modes of H7N9, which also include methods to reduce risk of seasonal flu and being infected with H7N9 in particular. For the knowledge assessment of MERS, participants were also asked to answer ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘not sure’ on two sections, namely scientific understanding and transmission modes of MERS.

Data analysis

Data were double-entered and cross-checked using Excel version 2013 (Microsoft Corp.; Redmond, USA). Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 13.0 (STATA Corp.; College Station, USA). All baseline socio-demographics were described as categorical variables (gender, age group, ethnicity, housing type and education level). Private housing includes condominium/landed/others, while primary education refers to no formal/primary education; secondary education refers to secondary/‘O’/‘A’ level; tertiary education refers to vocational/university and above. A chi-square test was used to determine if there was a statistical difference between participants who had versus those who had never heard of H7N9 and MERS. Multivariable logistic analysis, with Odds Ratios (OR) reported, were used to determine factors associated with awareness of H7N9 and MERS.

The scoring for knowledge of H7N9 and MERS encompassed the participant’s scientific understanding of the diseases, transmission modes and methods of reducing risk of infection. A negative-marking scoring method was used to reflect the participant’s true understanding of the diseases. Correct answers were scored with a positive value of one, incorrect answers were given a negative value of one and questions that were answered ‘not sure’ or omitted were given a value of zero. By proportion, the knowledge scores for H7N9 were scaled to a maximum score of 20 as there were a total of 12 questions and for MERS to a maximum score of 10 as there were a total of 6 questions. Multivariable linear regression analysis was used to determine factors associated with the summative H7N9 and MERS knowledge scores among respondents who had heard of H7N9 and/or MERS. Additionally, the study also analyzed key questions relating to the transmission of H7N9 and MERS to understand how well the participants knew about specific preventive measures to protect themselves; descriptive statistics was used for this with results expressed as percentages.

As the study population was partially recruited through opportunistic sampling of members in the same households, all logistic and linear regression analysis used a multilevel mixed-effects model with a random intercept to adjust for effects observed due to potential household clustering. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Participant’s characteristics

The socio-demographic characteristics of the 2969 respondents in the survey are described in Table 1. “Table 1 about here” A higher proportion of females was observed in our study population, and the mean age was 42.4 years (range: 16–96 years). Majority of respondents in the sample were of Chinese ethnicity (38.7%) and between the ages of 40–59 years old (38.2%). Majority of the respondents resided in public housing type of 4 rooms and above and about half surveyed had attained at least secondary education.

General awareness of H7N9/MERS

As illustrated in Table 1, a larger portion of respondents had never heard of MERS (79.4%) before as compared to H7N9 (53.2%). In terms of age group, 64.4% and 90.1% of the respondents aged 16–21 years had never heard of H7N9 and MERS respectively (P < 0.001). Among the different ethnic groups, 41.1% and 78.8% of the Chinese respondents had never heard of H7N9 and MERS respectively (P < 0.01). Among respondents living in public housing type of 3 rooms and below, 60.9% and 84.0% of them had never heard of H7N9 and MERS respectively (P < 0.001). With regards to education, 63.6% and 88.2% of the respondents with primary education had never heard of H7N9 and MERS respectively (P < 0.001). General awareness of both the diseases were not significantly different for both genders.

Multi-level multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2) “Table 2 about here” was done to determine factors associated with awareness of H7N9 or MERS. Regarding H7N9, individuals who were 40 years old and above (OR = 3.24, 95% C.I 2.21–4.77) or with at least secondary education (OR = 1.72, 95% C.I 1.25–2.37) were significantly more likely to hear of the disease compared to the reference groups of those aged 16–21 years or with primary education respectively. Compared with the Chinese, the Malay and Indian ethnic groups were significantly less likely to hear about H7N9 (OR = 0.40, 95% C.I 0.29–0.54 and OR = 0.35, 95% C.I 0.25–0.49 respectively). Respondents who relied on printed media or websites/ Internet for outbreak information were more likely (OR = 1.62, 95% C.I 1.23–2.13, and OR = 1.57, 95% C.I 1.16–2.11 respectively), while those who relied on word of mouth from their family members and/or relatives were less likely (OR = 0.58, 95% C.I 0.41–0.82) to have heard of H7N9.

Similarly, regarding MERS, those with at least secondary education (OR = 2.09, 95% C.I 1.43–3.06) or who relied on printed media or websites/ Internet for outbreak information (OR = 1.50, 95% C.I 1.10–2.03, and OR = 1.76, 95% C.I 1.28–2.43 respectively), were significantly more likely to hear of the disease. However, unlike H7N9, the Malays and other ethnic groups (OR = 1.48, 95% C.I 1.08–2.05, and OR = 2.53, 95% C.I 1.22–5.25 respectively), were significantly more likely to hear about MERS than the Chinese population. Adults aged 22 years and above (OR = 1.76, 95% C.I 1.10–2.83) were more likely to learn about MERS compared to the respondents aged 16–21 years.

Knowledge of H7N9/MERS

The respondent’s knowledge about scientific understanding and modes of transmission of H7N9 and MERS is reported in Tables 3 and 4 respectively. “Tables 3 and 4 about here” For H7N9 (N = 1389), respondents scored a mean of 9.2 (S.D ± 2.3) out of a possible maximum score of 20, while a mean of 5.9 (S.D ± 1.2) out of 10 was scored for MERS (N = 613). For H7N9, there were three key questions relating to the acquisition of H7N9 through poultry exposure. Out of those who were aware of H7N9, at least 60% of the respondents could answer the individual questions accurately. However, only 35% of them managed to answer all three questions correctly. In addition to the 53% of respondents who were not aware of H7N9, the total percentage of respondents who had inadequate knowledge of H7N9 was 83%. Similarly, inadequate knowledge of MERS is shown in Table 4. Out of the three questions regarding transmission modes of MERS, majority of the respondents could only provide correct answer to one question relating MERS transmission to being near a symptomatic infected person. A high percentage of respondents wrongfully thought that MERS can be transmitted through mosquito bites and exchanges of blood.

Frequency distribution of the respondents’ total knowledge score for H7N9 and MERS approximated a normal distribution, allowing the use of linear regression model for further analysis. After adjusting for all variables, multi-level multivariable linear regression analysis shows that among those who have heard of H7N9 or MERS, age group and ethnicity were significantly correlated to their knowledge scores of the diseases (Table 5). “Table 5 about here” In particular, older age groups were found to be positively correlated with the knowledge level. However, the Malays and Indians had a poorer understanding of both diseases as compared to the Chinese population. Additionally, respondents who were aware of H7N9 and relied on their friends and/or colleagues as their source of information were most likely to have a lower knowledge of H7N9. Respondents with at least secondary education and those residing in public housing type of 4 rooms and above were found to be positively correlated with their knowledge level of MERS.

Outbreak information source

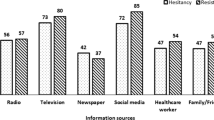

Majority of the respondents relied on traditional media channels such as television and/or radio (90.0%), and printed media (70.6%), as their information source for infectious disease outbreaks (Fig. 1). “Figure 1 about here” This is opposed to other sources such as websites/Internet (57.7%), and social media (43.9%) which were the least preferred choices. When the preferred information sources were stratified according to socio-demographic factors, the following statistically significant trends were observed: a) Age group: A higher percentage of respondents aged 40 years and above preferred television and/or radio (93.3–95.3%) and print (73.8–76.0%) as their information source as opposed to websites/ Internet (23.0–47.9%) and social media (14.1–35.8%). On the other hand, for respondents aged 16–39 years, there was a stronger preference for television and/or radio (84.5–85.2%) and websites/ Internet (78.1–83.1%) compared to print (58.3–67.3%) and social media (59.7–69.3%); b) Ethnicity: For Chinese, Malays and Indians, the top two preferred information sources were television and/or radio (92.1%, 89.7% and 87.1% respectively) and print (79.2%, 64.5% and 65.5% respectively). However, for the other minority races, television and/or radio (88.9%) and family (80.6%) were their top two choices; c) Housing: The percentages of the respondents who preferred television and/or radio were generally high (85.1–91.8%) regardless of housing type. On the other hand, there is a stronger preference for print and websites/internet as information sources among respondents staying in private housing (85.1% and 72.8% respectively) compared to public housing (64.8–72.5% and 51.7–59.6% respectively); d) Education: As the education level increased from primary to tertiary, the preference for print (58.8% to 73.5%), websites/ Internet (18.5% to 82.4%), social media (20.0% to 55.3%) and friends and colleagues (56.7% to 65.2%) as information sources increased too. However, the reverse trend was observed for television and/or radio, as 94.8% of the respondents with primary education preferred it as their information source as opposed to 84.1% of the respondents with tertiary education.

Discussion

The results showed an apparent lack of awareness on emerging infectious agents among the respondents surveyed, with only 46.8% and 20.6% having heard of H7N9 and MERS respectively. Among those aware of H7N9 or MERS, many had multiple misconceptions, as evident from their low knowledge scores, in particular for H7N9. Of particular concern is the lack of knowledge about transmission of H7N9 via poultry exposure. Despite the fact that risk of H7N9 infection was known to be highly attributed to poultry exposure, detailed questioning revealed that less than 40% of those aware of H7N9 could correctly answer all three questions related to acquisition of the infection via poultry exposure. Likewise for MERS, a higher proportion had misunderstood that transmission could occur through blood exchanges and mosquito bites. Majority of respondents were also unsure of the use of antiviral drugs to treat H7N9 and the current lack of vaccinations to prevent both infections.

The study showed a significant association between higher education levels (at least secondary education) and awareness of H7N9 or MERS, and similarly for knowledge scores on MERS. Such trends were observed in other studies that examined the association between education level and knowledge about infectious diseases [17, 36, 37]. As education is a major social determinant of health, particularly in health promotion and disease prevention [38], educating an individual on the requisite knowledge and skills will enable them to better protect themselves and their family by avoiding high-risk health behaviors.

The results also indicated that the older age groups had higher odds of hearing about and having better understanding and knowledge of H7N9 or MERS. Further subgroup analysis in our study found that the highest percentage of respondents who chose print media as their outbreak information source were between age 40–59 (76%). This is in line with the findings by Ahlers [39] and Shah et al. [40], who reported that the older generation place greater reliance on print media. We thus postulate that, as a result of regular exposure to print media, the older age groups were more likely to receive reported news of outbreaks in the print media, contributing to their greater awareness and understanding of H7N9 or MERS. However, the effects of age persisted, even when we adjusted for effects of different media sources, probably because of residual confounding, since the questions about media sources only assessed if they did or did not rely on particular media channels but did not assess the degree of exposure, which was likely different amongst the age groups.

There were significant associations observed between ethnicity and the level of awareness and knowledge of H7N9 or MERS in Singapore. Minority ethnic groups were less likely to hear about H7N9 as compared to the Chinese majority ethnic population. Moreover, among those who have heard of H7N9, the Malays and Indians also had lower knowledge scores. This corroborates the findings of a study conducted in Malaysia, where the Malay ethnic group was found to possess a lower knowledge of H1N1 [18]. However, this differs from the findings from a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) public knowledge study done in Singapore, which reported no significant associations between knowledge level and ethnicity [17]. Interestingly, the Malays and other ethnic groups were more likely to hear about MERS, but had lower knowledge scores on MERS as compared to the Chinese. Our findings could be due to a varied sense of risk perception resulting from the disparate media coverage in language mediums favoured by different ethnic groups in Singapore. Information of any new H7N9 infected cases could have received greater media coverage in the Chinese news given that cases occurred mainly in China. Moreover, minority ethnic groups were less likely to travel to China, and thus may not be as motivated to learn more about H7N9. Likewise for MERS, infections have been mainly located in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East [41] and hence, there was a specific health advisory, released by the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Singapore, targeting Umrah and Haj pilgrims traveling to Islamic pilgrimage sites in the Arabian Peninsula [42]. This could have caused a heightened awareness of MERS among the Malay Muslim community.

In terms of outbreak information source, the television and radio were found to be the most utilized among the respondents regardless of socio-demographic factors. Recent studies on outbreak information dissemination had reported traditional media channels to still be the main source of information, with minimal health information exchanged on social media [43,44,45,46]. Our findings are also congruent with the study conducted by Vijaya et al. [17] where the authors found that majority of the respondents depended on the television and printed media for timely and accurate information during the SARS outbreak in Singapore. Based on our results, print, websites/ Internet and social media could act as complementary information sources in Singapore but they should be targeted towards specific socio-demographic groups. For individuals aged 40 years and above or staying in private housing, print media were also preferred in addition to television and radio. Websites/ Internet were well utilized by individuals aged 16–39 years or with a tertiary education, while the use of social media as an outbreak information source was mainly observed in individuals aged 16–21 years old. In addition, respondents were most likely to have lower knowledge scores on H7N9 if they chose to hear from their friends and colleagues. This is substantiated by Scanfeld et al. [47] who reported that the public can be misled by inaccurate health information disseminated through word of mouth and social media.

As highlighted in the previous paragraphs, demographics contribute to significant differences in awareness and knowledge regarding emerging infections. These differences suggest a need to consider audience segmentation in the design and dissemination phase in order to convey outbreak information more effectively. Having a limited portion of people being aware and well-informed of these viruses in times of outbreak might result in panic and misleading information being disseminated through social channels. This could lead to adoption of unwanted practices instead of accurate preventive measures. Interestingly, during the outbreak of SARS, knowledge level on the disease itself was not associated with adoption of preventive measure but public trust was. Such studies [48, 49] highlight the fact that it is essential in the event of an outbreak, where responses need to be swift, for the public to be able to access accurate information on preventive measures through reliable channels in order to respond accordingly. Finally, identification and training of community leaders and motivated individuals on outbreak preparedness might further complement traditional media as another source of information.

There are strengths and limitations to the study. As respondents were recruited from diabetic and multi-ethnic cohorts, it has allowed us to assess our study objectives in a more vulnerable population group and also identify differences between ethnicities and note the need to consider audience segmentation during future outbreak communication. On the other hand, during the process of data collection, sources of bias include potential selection bias of respondents, as respondents were asked if they were willing to participate in the survey, resulting in volunteer bias and may not be truly representative of the general Singapore population. In addition, convenience sampling of respondents who were household members of contacted members of the original cohorts that our sampling strategy drew on comprised 78% of the total data set, resulting in grouped participants in the same household. This was partially accounted for by using the multilevel mixed-effects model with a random intercept term. Finally, the survey was conducted between June to December 2013, a period shortly after the news of the first case of human H7N9 was reported in March 2013 but almost a year after the first case of MERS was reported in September 2012. This temporal difference could have varied the duration of risk communication and public engagement for both infections at the point of survey and hence, impacted the level of awareness and knowledge on H7N9 or MERS.

Conclusion

As a multicultural society, Singapore presents a unique set of challenges for successful risk communication. Results of this study suggest that public health communication and risk dissemination regarding H7N9 or MERS were not optimal in Singapore. Public health education about infectious disease outbreaks should reach out more to the younger population, lower educated groups and ethnic minorities to equip them with better information on specific preventive measures. Despite the growing popularity of social media in Singapore, traditional media channels such as the television, radio, printed media as well as websites remain the primary source of outbreak information among respondents in this study. Future health communication strategies for emerging infectious diseases should consider audience segmentation and the most suitable media channels for disseminating risk information across various socio-demographic groups.

Moving forward, the study proposes that a concerted effort be orchestrated between the media and health authorities, to seamlessly communicate information through news articles about specific preventive measures the public can take to protect themselves during outbreaks. Future surveys should try to understand how local communities network and communicate and the barriers and facilitators for individuals to take action in the event of an outbreak. More studies should also be done to analyse the effectiveness of tailored messages. Qualitative studies in the form of focus groups may be useful to pre-test and assess the responses of multi-cultural audiences regarding uptake of information. This will benefit the design of health communications during early stages of development. Additionally, in-depth interviews can also be employed to elicit personal responses and concerns of the messages, for individuals who may be difficult to reach, particularly vulnerable groups who have limited writing and reading skills.

Abbreviations

- MERS:

-

Middle East respiratory syndrome

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- SARS:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SSHSPH:

-

Saw swee hock school of public health

References

Hui DS, Zumla A. Emerging respiratory tract viral infections. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21(3):284–92.

World Health Organization. Background and summary of human infection with influenza A (H7N9) virus. http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/latest_update_h7n9/en/ (2013). Accessed 30 Apr 2013.

Alsolamy S, Arabi YM. Infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Canadian Journal of Respiratory Therapy. 2015;51(4):102.

Ke Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, Huang L, Chen Z. Deaths associated with avian influenza a (H7N9) virus in China. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):159–60.

Chang SY, Lin PH, Tsai JC, Hung CC, Chang SC. The first case of H7N9 influenza in Taiwan. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1621.

To KK, Song W, Lau SY, Que TL, Lung DC, Hung IF, et al. Unique reassortant of influenza a (H7N9) virus associated with severe disease emerging in Hong Kong. J Infect. 2014;69(1):60–8.

William T, Thevarajah B, Lee SF, Suleiman M, Jeffree MS, Menon J, et al. Avian influenza (H7N9) virus infection in Chinese tourist in Malaysia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(1):142.

Li Q, Zhou L, Zhou M, Chen Z, Li F, Wu H, et al. Epidemiology of human infections with avian influenza a (H7N9) virus in China. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(6):520–32.

Singapore Tourism Board. http://www.stb.gov.sg/statistics-and-market-insights/marketstatistics/singapore tourism board_tourism sector performance q2 2014.pdf (2014). Accessed 27 Sept 2015.

Saw SH, Wong J. Advancing Singapore-China economic relations. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; 2014.

World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/mers-cov/en/ (2017). Accessed 29 Mar 2017.

World Health Organization. International health regulations (2005) 3rd ed. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246107/1/9789241580496-eng.pdf?ua=1 (2006). Accessed 29 Mar 2017.

Giuseppe GD, Abbate R, Albano L, Marinelli P, Angelillo IF. A survey of knowledge, attitudes and practices towards avian influenza in an adult population of Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8(1):36.

Leslie T, Billaud J, Mofleh J, Mustafa L, Yingst S. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding avian influenza (H5N1). Afghanistan Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008;14(9):1459.

Lin L, McCloud RF, Bigman CA, Viswanath K. Tuning in and catching on? Examining the relationship between pandemic communication and awareness and knowledge of MERS in the USA. Journal of Public Health. 2017;39(2):282–9.

Ma X, He Z, Wang Y, Jiang L, Xu Y, Qian C, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of healthcare workers in Chinese intensive care units regarding 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):24.

Vijaya K, Chan SP, Low YY, Foo LL, Lee M, Deurenberg-Yap M. Public knowledge, attitude, behaviour and response to the SARS outbreak in Singapore. Int J Health Promot Educ. 2004;42(3):78–82.

Wong LP, Sam IC. Knowledge and attitudes in regard to pandemic influenza a (H1N1) in a multiethnic community of Malaysia. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;18(2):112–21.

Gu H, Jiang Z, Chen B, Zhang JM, Wang Z, Wang X, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding avian influenza a (H7N9) among mobile phone users: a survey in Zhejiang Province, China. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2015;3(1):e15.

Hoda J. Identification of information types and sources by the public for promoting awareness of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia. Health Educ Res. 2016;31(1):12–23.

Peltz R, Avisar-Shohat G, Bar-Dayan Y. Differences in public emotions, interest, sense of knowledge and compliance between the affected area and the nationwide general population during the first phase of a bird flu outbreak in Israel. J Infect. 2007;55(6):545–50.

Vaughan E, Tinker T. Effective health risk communication about pandemic influenza for vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(S2):S324S32.

Blendon RJ, Benson JM, DesRoches CM, Raleigh E, Taylor-Clark K. The public's response to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(7):925–31.

Jardine CG, Boerner FU, Boyd AD, Driedger SM. The more the better? A comparison of the information sources used by the public during two infectious disease outbreaks. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140028.

Cowling BJ, Ng DM, Ip DK, Liao Q, Lam WW, Wu JT, et al. Community psychological and behavioral responses through the first wave of the 2009 influenza a (H1N1) pandemic in Hong Kong. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(6):867–76.

Taylor-Clark KA, Viswanath K, Blendon RJ. Communication inequalities during public health disasters: Katrina's wake. Health Commun. 2010;25(3):221–9.

Viswanath K, Thomson GE, Mitchell F, Williams MB. Public communications and its role in reducing and eliminating health disparities. Examining the health disparities research plan of the National Institutes of Health: Unfinished business. National Academies Press (US). 2006;1:215–53.

Department of Statistics Singapore. http://www.singstat.gov.sg/statistics/latest-data#16 (2017). Accessed 10 July 2017.

Win AM, Lim WY, Tan KH, Lim RB, Chia KS, Mueller-Riemenschneider F. Patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior in a representative sample of a multi-ethnic south-east Asian population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:318.

Nang EE, Van Dam RM, Tan CS, Mueller-Riemenschneider F, Lim YT, Ong KZ, et al. Association of television viewing time with body composition and calcified subclinical atherosclerosis in Singapore Chinese. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132161.

Lin Y, Huang L, Nie S, Liu Z, Yu H, Yan W, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) related to the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 among Chinese general population: a telephone survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):128.

Akan H, Gurol Y, Izbirak G, Ozdatli S, Yilmaz G, Vitrinel A, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of university students toward pandemic influenza: a cross-sectional study from Turkey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:413.

Manabe T, Tran TH, Doan ML, Do TH, Pham TP, Dinh TT, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, practices and emotional reactions among residents of avian influenza (H5N1) hit communities in Vietnam. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47560.

Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008.

Housing and development board. http://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/about-us/our-role/public-housing%2D-a-singapore-icon. Accessed 20 Feb 2018.

Janahi E, Awadh M, Awadh S. Public knowledge, risk perception, attitudes and practices in relation to the swine flu pandemic: a cross sectional questionnaire-based survey in Bahrain. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health. 2011;3(6):451–64.

Latiff LA, Parhizkar S, Zainuddin H, Chun GM, Rahiman MA, Ramli NL, et al. Pandemic influenza a (H1N1) and its prevention: a cross sectional study on patients’ knowledge, attitude and practice among patients attending primary health Care Clinic in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Global Journal of Health Science. 2012;4(2):p95.

Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(3):259–67.

Ahlers D. News consumption and the new electronic media. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics. 2006;11(1):29–52.

Shah DV, McLeod JM, Yoon SH. Communication, context, and community: an exploration of print, broadcast, and internet influences. Commun Res. 2001;28(4):464–506.

Shapiro M, London B, Nigri D, Shoss A, Zilber E, Fogel I. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: review of the current situation in the world. Disaster and Military Medicine. 2016;2:9.

Ministry of Health Singapore. Health advisory for Umrah and Haj pilgrims. https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/pressRoom/Current_Issues/2014/middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus%2D-mers-cov-/health-advisory-for-umrah-and-haj-pilgrims0.html (2015). Accessed 7 June 2017.

Lin L, Jung M, McCloud RF, Viswanath K. Media use and communication inequalities in a public health emergency: a case study of 2009–2010 pandemic influenza a virus subtype H1N1. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 4):49.

Lin L, Savoia E, Agboola F, Viswanath K. What have we learned about communication inequalities during the H1N1 pandemic: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):484.

Xiang N, Shi Y, Wu J, Zhang S, Ye M, Peng Z, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) relating to avian influenza in urban and rural areas of China. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):34.

Wong LP, Sam IC. Public sources of information and information needs for pandemic influenza a (H1N1). J Community Health. 2010;35(6):676–82.

Scanfeld D, Scanfeld V, Larson EL. Dissemination of health information through social networks: twitter and antibiotics. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(3):182–8.

Quah SR, Hin-Peng L. Crisis prevention and management during SARS outbreak. Singapore Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(2):364–8.

Deurenberg-Yap M, Foo LL, Low YY, Chan SP, Vijaya K, Lee M. The Singaporean response to the SARS outbreak: knowledge sufficiency versus public trust. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(4):320–6.

Acknowledgements

The research team would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Tai Bee Choo, Dr. Alex Cook and Mr. Gibson Gay for their advice on statistical analysis, and Dr. Raymond Lim for his contributions to the questionnaire design.

Funding

This study was funded by the NUHS (Research Office) from the NUHS H7N9 grant (grant number: NUHSRO/2013/143/H7N9/05).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC and WY were integral to the study conception and development of the methodology. WY and LT were involved in the questionnaire design and acquisition of the data. YA, WY, MC and PL participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data. YA, YR, MC, VL and PL drafted and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors gave the final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol and procedures were approved by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board (NUS IRB reference no.: 13–204). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. For participants aged 16 to 20 years, written informed consent was obtained from their parent or legal guardian in parallel.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, Y., Tan, Yr., Lim, W.Y. et al. Adequacy of public health communications on H7N9 and MERS in Singapore: insights from a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 18, 436 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5340-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5340-x