Abstract

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common and costly healthcare problems worldwide. Disability from LBP is associated with maladaptive beliefs about the condition, and such beliefs can be influenced by public health interventions. While socioeconomic status (SES) has been identified as an important factor in health literacy and inequalities, not much is known about the association between SES and beliefs about LBP. Therefore, this study examined the relationship between measures of SES and the belief that one should stay active through LBP in a representative sample of the general population in Alberta, Canada. We also examined the association between measures of SES and self-reported exposure to a LBP mass media health education campaign.

Methods

Population-based surveys from 2010 through 2014 were conducted among 9572 randomly selected Alberta residents aged 18–65 years. Several methods for measuring SES, including first language, education, employment status, occupation, and annual household income, were included in multivariable logistic regression modeling to test associations between measures of SES and outcomes.

Results

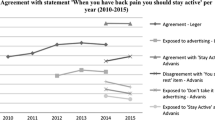

Univariable analysis showed that age, language, education, employment, marital status, and annual household income were significantly associated with the belief that one should stay active through LBP. In multivariable analysis, income was the variable most strongly correlated with this belief (odds ratios ranged from 1.04 to 1.62 for the highest income category, p = 0.005). Univariable analysis for exposure to the campaign showed age, language, education, employment, and occupation to be significantly associated with self-reported exposure, while only education (p = 0.01) and age (p = 0.001) remained significant in multivariable analysis.

Conclusions

Individuals with higher annual income appear more likely to believe that one should stay active during an episode of LBP. Additionally, targeted information campaigns are recalled more by low SES groups and may thus assist in reducing health disparities. More research is needed to fully understand the association between socioeconomic factors and LBP and to target campaigns accordingly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Socioeconomic status (SES), conceptualized as the social standing or class of an individual or group, has been identified as an important factor in health inequalities [1, 2]. People with higher SES tend to live longer, healthier lives, and suffer less from disease and disability [3, 4]. Furthermore, SES and disability appear to have a gradient relationship, with better health accompanying increases in SES [5]. Adler and Newman have proposed several pathways through which SES may influence health [6]. These include SES and environmental exposures (i.e. exposure to damaging agents in the work or home environment), SES and social environment (i.e. isolation and engagement in social networks), SES and health care (i.e. access, use, and quality of health care), and SES and behaviour and lifestyle [6].

With many pathways through which SES can influence health, many approaches to measure SES have been taken in health research. For example, level of education, occupation and occupational status, income and wealth, and geographical features have often been used as measures of SES [7,8,9]. SES is often investigated in health disparities research, but as of yet, not much is known about the relationship between socioeconomic factors and low back pain (LBP). Results of the few studies that have reported on this relationship are conflicting [10, 11]. Considering that LBP is one of the most prevalent disorders worldwide, and has an enormous economic and societal burden, it is important to identify factors that might help reduce the prevalence of LBP and its associated disability [12, 13].

Evidence indicates that staying active during a LBP episode leads to quicker recovery and clinical practice guidelines consistently recommend remaining active despite LBP [14]. Disability among adults with LBP has been found to be associated with maladaptive LBP beliefs, such as the belief that movement will cause physical damage to the spine and that bed rest is needed for managing LBP [15,16,17,18]. Indeed, beliefs about LBP in the general public tend to be maladaptive [19,20,21,22,23,24]. This has led developers of mass media interventions to focus on changing beliefs about activity in the hope that it will lead to more adaptive beliefs that change associated health behaviour (i.e. more activity during LBP episodes and thus less disability). Unfortunately, most mass media campaigns have resulted in improvements in beliefs, but have failed to result in sustainable changes in associated disability behaviours [25,26,27]. Various explanations have been suggested, many of which were campaign-related.

One factor that may have influenced the success of LBP campaigns is SES. Personal and environmental factors play a role in health behaviour, as many health models have suggested. For example, education has been found to be related to LBP beliefs [28]. Individuals with a higher level of education may be more adept at sifting through the vast amount of information about LBP and adopting more adaptive beliefs about their LBP (i.e. believing that one should stay active during an episode of LBP) [29, 30]. Since none of the previous mass media campaigns have examined the relationsship between SES and campaign effects, it is possible that more targeted messaging could result in better outcomes. This study examined the relationship between measures of SES and the belief that one should stay active through LBP among the general population of Alberta, Canada. We also examined the association between measures of SES and exposure to a mass media campaign aimed at improving back beliefs.

Methods

Design

Over the past decade, the Workers’ Compensation Board and partners in the province of Alberta, Canada have undertaken a mass media campaign designed to improve back beliefs among the general public. This campaign was evaluated in a previous study [25]. From 2010 through 2014, annual data on public beliefs continued to be gathered using cross-sectional surveys. These surveys contained the key question related to beliefs about staying active during LBP that was also used during the initial study [25]. The Workers’ Compensation Board-Alberta provided access to the survey data that contained measures of LBP beliefs along with several demographic characteristics. Informed consent was not written, but obtained by the polling firms verbally for telephone surveys and online for web-based surveys. Consent was also implied through completion of the survey. The University of Alberta’s Health Research Ethics Board approved this study.

Study population

Between 2010 and 2014, 9572 randomly selected Alberta residents aged 18–65 years were surveyed. The sample appeared representative of the overall population of adult Albertans based on a comparison with region, sex, and age information available in the most recent Statistics Canada census information [31]. Experienced polling firms collected data using Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviews (n = 4500) and web-based surveys (n = 5072). The telephone surveys were conducted in January 2010 (n = 900), January 2011 (n = 900), July 2013 for the year 2012 (n = 900), November 2013 for the year 2013 (n = 900) and May 2014 (n = 900). Web-based surveys were conducted in January 2010 (n = 1002), January 2011 (n = 1066), July 2013 for the year 2012 (n = 1002), November/December 2013 for the year 2013 (n = 1001) and May 2014 (n = 1001). Respondents to the telephone interviews were randomly selected while the web-based surveys were not random (i.e. self-selected respondents to the online survey). Since the majority of respondents were self-selected, we were unable to calculate response rates.

Outcome measures

The surveys contained the key belief question from the original campaign surveys regarding staying active with back pain. Respondents were asked their level of agreement (from 1-Completely Disagree to 5-Completely Agree) with the statement “If you have back pain you should try to stay active”. Level of agreement with this statement was considered the primary outcome measure for the current study, and responses were dichotomized by combining the agree options (4 and 5) into one category and disagree options (1 and 2) into a second category with the neutral option (3). Agreement with this statement was considered an adaptive back belief, while not agreeing with the statement was considered a maladaptive back belief. Although there has been little formal reliability or validity testing of this outcome measure of beliefs about LBP, the previous study by Gross et al. highlights the validity of the belief question [25]. It has been used in research performed in Scotland and Canada, and in both locations it was capable of detecting changes in general public back pain beliefs [25, 26]. The surveys also inquired about respondents’ exposure to campaign messaging, asking whether they recalled seeing or hearing any advertising that says “Back pain: Don’t take it lying down” or advising that it is important to stay active through back pain. This self-reported exposure to campaign messaging was considered a secondary outcome measure for this study.

Available measures of SES that were used as independent variables were region of residence (Edmonton/Calgary or other region in Alberta, where Edmonton/Calgary were considered urban and other regions were considered rural), the language respondents first learned at home in their childhood (French/English or other, where French and English were considered native and other languages were considered immigrant), level of education, employment situation, occupation, marital status, income category, and the number of people in the respondents’ household. Education, employment, occupation, and marital status had multiple categories and were collapsed into variables with more meaningful categories for analysis. The specific categories used can be seen in Table 1. Furthermore, the surveys contained basic descriptive information regarding characteristics of the study population. This included type of survey (phone- or web-based), age category, and sex of respondents. The original survey items used in this study are shown in Additional file 1.

Data analysis

Descriptive demographic and SES characteristics of the sample population were summarized. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify SES measures associated with back beliefs as well as campaign exposure. For the continuous variable (i.e. number of people in respondents’ household), a test for linearity with the outcome measures was performed first. As the assumption of linearity was not violated, this variable was kept as continuous in all models. All SES variables were entered into univariable models first. Variables that were significant in univariable models were then entered into a final multivariable model. However, in cases where eligible variables were highly correlated, as measured by Cramer’s V (>0.90), only the most significant variable was entered to avoid problems with collinearity. Hosmer-Lemeshow tests were performed to examine goodness-of-fit. For all analyses, significance levels were set to a p-value of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 (Armonk, New York).

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of the sample population. The majority of respondents were older than 44 years of age, female, had completed the web-based survey, lived in an urban region, and their native language was English and/or French. The average household consisted of 2.7 people, and one third of respondents reported an annual household income of $100,000CDN or more. Furthermore, 67.6% of respondents reported agreeing with the statement “If you have back pain you should try to stay active”, and 42% of respondents reported being exposed to campaign advertising. Most respondents were married, had completed College or Technical training, and were employed full-time. The types of occupations reported by the respondents varied widely, but most respondents (44.2%) were homemakers, students, retirees, or unemployed.

Logistic regression modeling ‘stay active’ item

Univariable logistic regression analysis showed statistically significant associations between agreement with the ‘Stay Active’ item, age, and several SES measures. People that learned a language other than English and/or French as their first language were less likely to agree with the item (Odds Ratio (OR) 0.78, 95%-Confidence Interval (CI) 0.63–0.98, p = 0.03). A higher educational level was positively related to agreement with the item, and there appeared to be a significant and gradient increase (OR 1.23 and 1.25 for college/technical training and university education respectively, both p = <0.001). Homemakers, retirees, students, and unemployed people were less likely to agree with the item than people that were employed either full-time or part-time (OR 0.88, 95%-CI 0.78–1.00), and this was statistically significant (p = 0.05). Marital status was also significantly related to agreement with the item. People who were married or in common law union were more likely to agree than single people (OR 1.34, 95%-CI 1.20–1.51, p = <0.001), as were people that were divorced, separated, or widowed (OR 1.31, 95%-CI 1.13–1.53, p = <0.001). Having an income between $40,000 and $59,999, between $80,000 and $99,999, or >$100,000 led to a significant increase in agreement with the statement, compared to having an income of $19,999 or less. Respective ORs for these income categories were 1.24 (95%-CI 1.00–1.55, p = 0.05), 1.41 (95%-CI 1.12–1.78, p = 0.004), and 1.66 (95%-CI 1.34–2.05, p = <0.001).

Variables entered into the multivariable logistic regression analysis for agreement with the ‘stay active’ statement included age, educational level, employment situation, marital status, and income category. While language was significant in the univariable model, there were insufficient cases in the dataset to run this variable in the multivariable model. The only association that remained significant in multivariable regression was that between agreement with the statement and income (p = 0.005). A Hosmer-Lemeshow test for the multivariable model showed a p-value of 0.16 (X2 11.9 with 8 degrees of freedom), suggesting that the data fit the model. Table 2 shows the crude and adjusted associations between the ‘Stay Active’ item and SES-measures.

Logistic regression modeling for campaign exposure

Table 3 shows the associations between campaign exposure and SES measures. Univariable regression showed a significant association between campaign exposure and a first language other than English/French, where this group was less likely to remember being exposed to campaign advertising than people that learned English and/or French as their first language (OR 1.41, 95%-CI 1.06–1.87, p = 0.02). The association between campaign exposure and overall educational level was not significant (p = 0.06), while respondents with university education were significantly less likely to remember being exposed to the campaign than respondents with a high school diploma or a lower educational level (OR 1.17, 95%-CI 1.02–1.34, p = 0.03). A significant association was also found between occupation and campaign exposure (p = 0.003), where respondents who were homemakers, students, retirees, or unemployed were less likely to remember being exposed to the campaign than manual workers (OR 1.24, 95%-CI 1.01–1.52, p = 0.04). Lastly, a significant association was observed between age categories and campaign exposure (p = <0.001).

Age, educational level, and occupation were entered into the multivariable logistic regression for campaign exposure. While language was a significant determinant in the univariable model, there were insufficient cases in the dataset to run this variable in the multivariable model. Employment status was not entered into the multivariable model, because it showed a high correlation with occupation (Cramer’s V = 0.92). The associations between campaign exposure and educational level and age remained significant in the multivariable model (p < 0.05), while occupation became non-significant. Respondents with university education were significantly less likely to remember being exposed to the campaign than respondents with a high school diploma or lower education (OR 1.22, 95%-CI 1.04–1.43, p = 0.02). A Hosmer-Lemeshow test for the multivariable model showed a p-value of 0.40 (X2 8.30 with 8 degrees of freedom), again suggesting a good fit of data.

Discussion

The current study examined associations between various measures of SES and having adaptive beliefs about back pain (i.e. agreeing with the statement ‘If you have back pain you should try to stay active’). We also examined associations between SES measures and self-reported exposure to a mass media campaign highlighting the importance of staying active through an episode of back pain. Results suggest that annual household income, as s measure of SES, was significantly associated with beliefs about LBP. We also observed a significant association between educational level and self-reported exposure to campaign advertising, where respondents with a high level of education were less likely to remember being exposed to campaign advertising (OR 1.22, p = 0.02). This may be due to the nature of the advertising, which targeted industries and workplaces with high risk of back pain (e.g. posters were sent out to construction and manufacturing type workplaces, but they were not sent out to offices or workplaces with a high ratio of university educated workers).

The targeted nature of the campaign is an important factor to keep in mind when interpreting our results. It may be that the LBP campaign did not yield any new information for higher educated respondents, which did not trigger them to remember this campaign. Recent studies have shown that tailored messages and targeted campaigns appear to stimulate greater cognitive activity among recipients than messages that are not tailored [32]. Making information relevant to the target audience has a better chance of effectiveness and is more likely to produce positive changes in health-related behavior [32, 33]. However, adequate exposure to the messages remains important, and supportive activities and policies can contribute to better behavioural or cognitive outcomes [33]. Additionally, targeted information campaigns may assist in reducing health disparities because in this study the targeted campaign was recalled more by low SES groups. This suggests the campaign reached and was understood by its intended audience. If low SES patients’ beliefs become more aligned with those of high SES patients, then recovery from LBP may improve to be similar to recovery rates of high SES groups. However, given that other studies have found that changed beliefs do not necessarily lead to changed actions [25,26,27], more research to help people translate realigned beliefs into new behaviours is needed.

In our univariable models, several SES measures were associated with adaptive back beliefs regarding staying active through LBP. For example, significant associations were observed between the LBP belief item and language, education, employment, and income. Learning a first language other than English or French, which could be interpreted as being immigrant to Canada, was a significant determinant for not agreeing with the ‘stay active’ item. When looking at language as a determinant for racial or immigrant status, our finding is in line with other research that suggests racial and ethnic disparities exist in health care [34, 35]. Specific to pain-related issues, a previous review showed that such disparities are prominent in pain perception, assessment, and treatment of pain, which underlines our finding that immigrant respondents usually are less likely to have adaptive beliefs about staying active through back pain [36]. Education, employment, and income category were also significantly associated with adaptive LBP beliefs in univariable models, which is in line with other research showing that more education is linked to higher income, and that both are associated with better health [37, 38]. Employment status (employed versus unemployed) might be a mediator between education and income, with more education being linked to higher employment rates, and being employed leading to higher income than being unemployed.

Although little is known about the relationship between SES and beliefs about LBP, our results are consistent with a review of survey data from two U.S. national surveys [39]. This study suggests that prevalence of LBP declines with an increase in education and income. Another review on formal education and LBP suggested that low education is associated with longer duration and higher recurrence of LBP [40]. In general, both higher incomes and higher levels of education have been reported as positively associated with healthy behaviour and thus positive health outcomes [6,7,8,9, 41]. However, the potential mechanisms through which SES influences LBP are unclear. One explanation might be that higher educational levels are related to healthy behaviour (e.g. exercise habits), less exposure to occupational risk factors (e.g. heavy manual work), and to higher incomes. Higher incomes can further reduce occupational and environmental risk factors (e.g. better living conditions), increase access to preventive health services, and aid in implementing healthy behaviours. However, other known and unknown factors may influence the relationship between SES and LBP, making the understanding of underlying mechanisms difficult. Furthermore, evidence has suggested that correlations between education, income, and other SES measures are modest, and that SES measures are not interchangeable [7]. Different SES factors can affect health at different times in life, on different levels, and through various causal pathways [7]. SES measures can further interact with other respondent characteristics, such as age. For example, older people have had more time to generate wealth than younger people, despite generally reporting lower incomes than younger people due to being retired, unemployed, or unable to enter the labour market. This interplay between various SES and non-SES measures further complicates interpretation of the relationship between SES and health.

Our results were based on a large, population-based sample that appeared representative of the overall target population based on recent census information available from Statistics Canada [31]. This improves generalizability of these results. However, the current study encountered some limitations. Unfortunately, no information on campaign exposure was available for the years 2010 and 2011, and no control group was available from areas without campaign exposure. We also did not have data on self-reported LBP to relate to measures of SES, and future studies should ideally include data on self-reported LBP. Furthermore, while most of the SES measures had many categories, not all categories were meaningfully interpretable and were collapsed. For example, 11 random categories were available for the ‘occupation’ variable, which was subsequently collapsed into 5 meaningful categories. While it has been recommended that researchers use many categories in order to establish knowledge on which SES factors specifically influence health, the categories chosen must be meaningful and preferably based on evidence [7]. Furthermore, the partially non-randomized sample (web-based survey) might have influenced our results and the cross-sectional nature of the surveys prevented examination of individual-level changes in LBP beliefs due to the campaign.

Conclusion

Individuals with higher annual household income appear more likely to believe that one should stay active during an episode of LBP. Additionally, targeted information campaigns are recalled more by low SES groups and may thus assist in reducing health disparities. More research is needed to fully understand the association between socioeconomic factors and LBP and to target campaigns accordingly.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

References

American Psychological Association. Socioeconomic Status office. Fact Sheet Work, Stress, and Health & Socioeconomic Status. http://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/factsheet-wsh.pdf. Accessed 9/28/2016.

Siegrist J, Marmot M. Health inequalities and the psychosocial environment – two scientific challenges. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(8):1463–73.

Dalstra JAA, Kunst AE, Borrell C, Breeze E, Cambois E, Costa G. Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: an overview of eight European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(2):316–26.

Huisman M, Kunst AE, Bopp M, Borgan JK, Borrell C, Costa G, et al. Educational inequalities in cause-specific mortality in middle-aged and older men and women in eight western European populations. Lancet. 2005;365(9458):493–500.

Minkler M, Fuller-Thomson E, Guralnik JM. Gradient of disability across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:695–703.

Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff. 2002;21(2):60–76.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi K, Metzler M, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research. One size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294(22):2879–88.

Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1013–23.

Galobardes B, Lynch J, Smith GD. Measuring socioeconomic position in health research. Br Med Bull 2007;81–82(1):21–37.

Hestbaek L, Korsholm L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Ohm KK. Does socioeconomic status in adolescence predict low back pain in adulthood? A repeated cross-sectional study of 4,771 Danish adolescents. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1727. doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0796-5.

Macfarlane GJ, Norrie G, Atherton K, Power C, Jones GT. The influence of socio-economic status on the reporting of regional and widespread musculoskeletal pain: results from the 1958 British birth cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008; doi:10.1136/ard.2008.093088.

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:743–800.

Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J. 2008;8:8–20.

Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Lin C-W, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(12):2075–94.

Briggs AM, Jordan JE, Buchbinder R, Burnett AF, O’Sullivan PB, Chua JYY, et al. Health literacy and beliefs among a community cohort with and without chronic low back pain. Pain. 2010;150(2):275–83.

Elfering A, Mannion AF, Jacobshagen N, Tamcan O, Muller U. Beliefs about back pain predict the recovery rate over 52 consecutive weeks. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35(6):437–45.

Burnett AF, Sze CC, Tam SM, Yeung KM, Leong M, Wang WTJ, et al. A cross-cultural study of the back pain beliefs of female undergraduate healthcare students. Clin J Pain. 2009;25(1):20–8.

Urquhart D, Rj B, Cicuttini FM, Cui J, Forbes A, Davis SR. Negative beliefs about low back pain are associated with high pain intensity and high level of disability in community-based women. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2008;9:148.

Darlow B, Perry M, Stanley J, Mathieson F, Melloh M, Baxter GD, et al. Cross-sectional survey of attitudes and beliefs about back pain in New Zealand. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004725. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004725.

Gross DP, Ferrari R, Russell AS, Battie MC, Schopflocher D, Hu RW, et al. A population-based survey of back pain beliefs in Canada. Spine. 2006;31(18):2142–5.

Goubert L, Crombez G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Low back pain, disability and back pain myths in a community sample: prevalence and interrelationships. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):385–94.

Ihlebaek C, Eriksen HR. Are the ‘myths’ of low back pain alive in the general Norwegian population? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2003;31(5):395–8.

Buchbinder R, Jolley D, Wyatt M. Population based intervention to change back pain beliefs and disability: three part evaluation. BMJ. 2001;322:1516–20.

Klaber Moffett JA, Newbronner E, Waddell G, Croucher K, Spear S. Public perceptions about low back pain and its management: a gap between expectations and reality? Health Expect. 2000;3(3):161–8.

Gross DP, Russell AS, Ferrari R, Battié MC, Schopflocher D, Hu R, et al. Evaluation of a Canadian back pain mass media campaign. Spine. 2010;35(8):906–13.

Waddell D, O’Connor M, Boorman S, Torsney B. Working backs Scotland: a public and professional health education campaign for back pain. Spine. 2007;32:2139–43.

Werner EL, Ihlebaek C, Laerum E, Wormgoor ME, Indahl A. Low back pain media campaign: no effect on sickness behaviour. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71(2):198–203.

Krismer M, Tulder M van. Low back pain (non-specific). Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21(1):77–91.

Tan BK, Smith AJ, O’Sullivan PB, Chen G, Burnett AF, Briggs AM. Low back pain beliefs are associated to age, location of work, education and pain-related disability in Chinese healthcare professionals working in China: a cross sectional survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:255.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. JGIM. 2005;20(2):175–84.

Statistics Canada, Tables by subject: Population and demography. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/ind01/l2_3867-eng.htm. Accessed 10/14/2016.

Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: strategies for enhancing information relevance. American Journal of Health Behaviour. 2003;27(3):S227–S232(6).

Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376(9748):1261–71.

Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. JNMA. 2002;94(8):666–8.

Farmer MM, Ferraro KF. Are racial disparities in health conditional on socioeconomic status? Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):191–204.

Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, et al. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4(3):277–94.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States. With special feature on socioeconomic status and health. Hyattsville, MD. 2011;2012

World Health Organization. Health Impact Assessment (HIA): The determinants of health. http://www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en/. Accessed 17/10/2016.

Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin B. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from the U.S. National Surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31(23):2724–7.

Dionne CE, Von Korff M, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA, Barlow WE, Checkoway H. Formal education and back pain: a review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:455–68.

Duncan GJ, Daly MC, McDonough P, Williams DR. Optimal indicators of socioeconomic status for health research. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1151–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the EMGO+ Institute for providing funding support and the Workers’ Compensation Board of Alberta, Leger Marketing, and Advanis Inc. for provision of data.

Funding

This study was supported by the EMGO+ Institute for Health and Care Research Travel Grant. The funding party did not have any role in design of the study, in collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

AS and DPG designed the study and discussed analysis. AS, GPB, and DPG discussed results, and all authors were involved in interpretation of results. AS wrote the initial manuscript, GPB, FGS, JRA, and DPG edited subsequent versions of the manuscript, and approved of the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of Alberta’s Health Research Ethics Board approved this study. Consent to participate was obtained by the survey polling firms who collected data.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Survey questionnaire items. Shows the original survey questions that were used in this study. (DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Suman, A., Bostick, G.P., Schaafsma, F.G. et al. Associations between measures of socio-economic status, beliefs about back pain, and exposure to a mass media campaign to improve back beliefs. BMC Public Health 17, 504 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4387-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4387-4