Abstract

Background

Homeless men are highly vulnerable to acquisition of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) compared to the general population. In Brazil, a country of continental dimensions, the extent of HCV infection in this population remains unknown. The objective of this study is to investigate the epidemiological profile of exposure to HCV in homeless men in Central Brazil.

Methods

A Cross-sectional study was conducted in 481 men aged over 18 years attending therapeutic communities specialized in the recovery and reintegration of homeless people. Participants were tested for anti-HCV markers using rapid tests. Poisson regression analysis was used to verify the risk factors associated with exposure to HCV.

Results

The prevalence of HCV exposure was 2.5% (95.0% CI: 1.4 to 4.3%) and was associated with age, absence of family life, injection drug use, number of sexual partners, and history of sexually transmitted infections (STI). Participants reported multiple risk behaviors, such as alcohol (78.9%), cocaine (37.1%) and/or crack use (53.1%), and inconsistent condom use (82.6%). Injection drug use was reported by 8.7% of participants.

Conclusions

The prevalence of HCV infection among homeless men was relatively high. Several risk behaviors were commonly reported, which shows the high vulnerability of this population. These findings emphasize the need for the development of specific strategies to reduce the risk of HCV among homeless men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem worldwide [1, 2]. It is estimated that 2.8% of the world population, which corresponds to 185 million people, is living with the chronic form of hepatitis C, and that each year about 350 thousand people die as a result of its complications, such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [2, 3]. In Brazil, the prevalence of HCV infection in the general population is 1.3%, with differences among Brazilian regions (from 0.68% in the Northeast to 2.1% in the North); in the Midwest, a prevalence of 1.6% is estimated among individuals over 20 years-old [4].

HCV is transmitted predominantly by the parenteral route, but it can also be transmitted from mother-to-child and through sexual contact [5]. Therefore, individuals who practice specific risk behaviors, such as injection and non-injection drug use, sharing needles and syringes, unprotected sex, and multiple sexual partners, are at increased risk of HCV infection [4, 6, 7]. In addition to behavioral determinants, factors related to social and programmatic vulnerabilities, such as low income and education, discrimination based on social condition or sexual orientation, loss of family ties, and difficulty accessing health services may contribute indirectly to the spread of HCV, especially in key populations (non-injection and injection drug users, sex workers, men who have sex with men, and homeless people) [8, 9].

It is estimated that each year about 60 to 70% of cases of hepatitis B and C occur in vulnerable populations, including people living on the street [8]. HCV infectionin homeless people, a population mainly composed of men [10–12], can be conceptualized by the interaction of individual, social, and programmatic vulnerabilities that expose this population to risk factors that can increase their risk for infection [9]. Injection and not injection drug use, sharing paraphernalia for drug use, tattoos, sharing of personal care items, prior incarceration, and sexual risk behaviors have been associated with HCV infection in this population [13, 14].

Studies have shown a high prevalence of HCV among homeless men, ranging from 25.1 to 34.3% in Asia [15, 16], 19.0 to 26.5% in Europe [9, 17], and 4.84 to 66.0% in North America [18, 19]. In 2012, a global systematic review and meta-analysis estimated a prevalence of 21.0% (95% CI: 13.0 to 28.0%) in homeless men [12]. In Brazil, the only study conducted in homeless men, found a prevalence of 8.5% in 330 individuals in São Paulo [11].

In Brazil, a country of continental dimensions, the extent of HCV infection among homeless men remains unknown, with the only study conducted about HCV epidemiology in this population being limited to the Southeastern region [11]. The approach to this infection requires different strategies both for diagnosis and for compliance with prevention and treatment protocols in the homeless. We believe that this study will contribute to the strengthening of public health and social policies aimed at the prevention of HCV in homeless person, since it presents important data about the epidemiological profile of the infection in this population in Brazil. In this way, the determinants of HCV exposure presented in this investigation can be taken into account in the planning and implementation of health promotion and infection prevention and comprehensive care actions, with emphasis on strengthening health education actions, availability of diagnostic tests in institutions that serve homeless persons, early treatment, provision of condoms, and epidemiological surveillance. In order to bridge the current gap in knowledge, this study aims to investigate the epidemiology of HCV exposure in homeless men in Central Brazil.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in homeless men between August and November 2015. The sample consisted of individuals attending four specialized therapeutic communities located in Goiás, Central Brazil, designed with the goal of recovery and reintegration into society for this population. Homeless men were eligible if over 18 years-old. Participants in obvious withdrawal, psychotic break, or psychomotor agitation were considered ineligible.

To calculate the sample size, a statistical power of 80% (β = 20%) with a significance level of 95% (α = 0.05) were considered, and a prevalence of anti-HCV of 8.5% was assumed in the homeless population of São Paulo [11] with design effect correction of 3.0. Therefore, the minimum sample size needed to estimate the prevalence in the study population was 359 participants, which was increased by 10% to correct for loss and refusal, totaling a sample of 395 participants.

Data were collected through interviews using a structured questionnaire containing socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical risk factors for HCV infection. The questionnaire was based on previously validated studies in populations of homeless and tested in a pilot study [11, 17–22]. Antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) were detected by using rapid tests on capillary blood collected by finger-stick, as recommended by the World Health Organization and the Ministry of Health of Brazil for vulnerable populations [23, 24]. The test was interpreted ten minutes after the collection and the result was given to the patient during post-test counseling.

The dependent variable of this study was the exposure to HCV. The independent variables included sociodemographic characteristics, factors related to parenteral exposures, and risk behaviors.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical program STATA, version 12.0. The Anderson-Darling test was used to verify the normality of quantitative variables [25]. Continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables in absolute and relative frequencies. The prevalence of exposure HCV was estimated with 95% confidence intervals (95.0% CI). Bivariate regression analysis was performed to verify the potential exposure factors associated to HCV. Variables with p < 0.10 were included in a Poisson regression model with robust variance and considered statistically significant with values of p < 0.05 [26]. Studies indicate that in cross-sectional studies, Poisson models with robust variance are better alternatives than logistic regression. This modeling has been suggested as a good alternative to obtain estimates of adjusted prevalence ratios for potential confounding variables in epidemiological studies. In addition, the use of robust methods for estimating variance in Poisson models corrects the overestimation of variance, and produces adequate confidence intervals, especially when inserted into quantitative variable models [26, 27].

Ethical aspects

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinics Hospital of Federal University of Goiás, under protocol number 1236774. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Individuals with positive results were referred to specialized services for further diagnostic confirmation, clinical evaluation, and treatment.

Results

Overall, 511 individuals were invited to participate in the study; of them, 30 declined, resulting in a response rate of 94.1%, bringing the final study sample to 481. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The median age was 36 years (IQR: 36–50), and schooling was eight years (IQR: 6–11). Most of the participants were single (86.3%). The median duration of street experience was 90 days (IQR: 7–1.095).

Participants reported risk behaviors for HCV infection, such as alcohol use in the previous 30 days (78.9%), cocaine use (37.1%), crack use (53.1%), and irregular condom use (82.6%). Injecting drug use was reported by 8.7% of the participants.

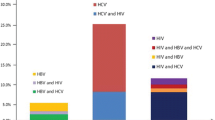

Anti-HCV markers were detected in 12 of the participants, resulting in a prevalence of 2.5% (95.0% CI: 1.4 to 4.3%). In the bivariate analysis, exposure to HCV was significantly associated with age, education, family life, and injection drug use (p < 0.05). These variables, prior blood transfusion (p = 0.089), and STI history (p = 0.086) were included in the Poisson regression model (Table 1).

In the multiple regression analysis, being without family (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR]: 4.45; p = 0.012), injecting drug use (aPR: 19 2; p < 0.001), and STI history (aPR: 3.34; p = 0.027) remained as risk factors for HCV infection. HCV prevalence increased by 7% for each year of age (aPR: 1.07; p = 0.008) and 7% for each sexual partner in the last year (aPR: 1.07; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study investigated the HCV prevalence and risk factors among homeless men. To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in homeless men in Central Brazil. The information in this study provides important data on the extent of HCV in this population, data that can guide actions to prevent and control infection by health services and social assistance to homeless persons. Our findings show a high prevalence of HCV infection in homeless men and an association with age, lack of family life, injection drug use, number of sexual partners, and STI history. In addition, the sample reported high rates of risk behaviors, suggesting that homeless represent a high risk group for pathogens transmitted by the parenteral route and/or sexually.

In this study, the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies was 2.5% (95.0% CI: 1.4 to 4.3%), higher than that found in the male population of Brazil (1.15%; 95.0% CI: 0.92–1.37%; χ2 = 6.823; p = 0.009), confirming the vulnerability of homeless men to this infection [28]. However, this rate was lower than the prevalence estimated in homeless men in São Paulo (Southeast Region of Brazil) (9.7%; 95.0% CI: 6.7 to 13.9%) [11]. The difference in prevalence between São Paulo and Goiás can be explained by the different socio-demographic characteristics and risk behaviors of the populations of the two locations. Furthermore, in Brazil, HCV infection has an uneven geographical distribution, with most infected individuals concentrated in the South and Southeast regions, including São Paulo [4].

Considering homeless men in other geographic locations, the prevalence of anti-HCV was lower than that estimated in countries such as Iran (25.1%; 95.0% CI: 21.0–28.5%) [15], England (27.0%; 95.0% CI: 19.0–37%) [9], and USA (31.0%; 95.0% CI: 26.6–35.7%) [5]. Differences in prevalence can be explained, in addition to different endemicity profiles between countries, by variations in the population characteristics and risk behaviors, especially injection drug use. In fact, in this study, the prevalence of injection drug use (8.7%) was low compared to the studies conducted in Iran (27.6%) [15], England (34.0%) [9], and USA (28.2%) [5].

This study found an association between age and HCV exposure, as shown in other studies conducted in vulnerable populations [21, 22, 29–31]. This result may reflect the cumulative risk and multiple parenteral and sexual exposures of these individuals throughout their life [21, 32].

An important determinant of housing on the street includes family problems, drug addiction, and financial difficulties [33], which enhances the social vulnerability of the homeless population. Interestingly, we found an association between the absence of family ties and exposure to HCV. The absence of a family bond can contribute to infections transmitted parenterally and/or sexually, since people without social support and stability may have greater needs as far as individual satisfaction and pursue them through risk behaviors, including injection drug use, unsafe sex, sex work, and multiple sexual partnerships [34–37]. In addition, individuals without social support have greater difficulty accessing health services, which tends to increase the risk of exposure to HCV and other pathogens. Further studies are needed to assess the impact and contribution of social vulnerability in HCV infection in the homeless population.

In both developing and developed countries, most cases of HCV infection occur in people who inject drugs [2]. Worldwide, approximately 60 to 80% of injection drug users are positive for HCV. These individuals are at increased risk for hepatitis C, mainly due to sharing needles and syringes [38]. In this study, injection drug use was strongly linked to HCV exposure, as found in the general population of Brazil [4] and several other studies conducted on homeless people [15, 18, 30, 32, 39]. In addition, among men who reported injection drug use, more than half (57.1%) reported sharing drug paraphernalia (data not shown). These results confirm the efficient transmission of HCV by the parenteral route [29].

Exposure to HCV was associated with STI history and multiple sexual partners. Some studies have shown HCV-RNA detection in semen, vaginal secretions, seminal fluid, saliva, and cervical smear, suggesting the possibility of sexual transmission of the virus, also among homeless men [40, 41]. In addition, factors such as multiple sexual partners, use of illegal drugs before or after sex, inconsistent condom use, and co-infection of some STIs (viral or bacterial) may contribute to sexual transmission of HCV in vulnerable populations [41, 42].

This study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The cross-sectional nature does not allow the establishment of cause and effect relationships between HCV exposure and the variables investigated. The data were self-reported, capable of memory and response bias. The study included only men linked to therapeutic communities who consequently do not represent the entire male population living on the streets in Goiás. This study used a positive anti-HCV rapid test as a marker without confirmation of active infection through detection of viral RNA, not differentiating between current or past infection. However, the sensitivity and specificity of the rapid test is high when using blood, serum or plasma (98.4% of sensitivity and 99.7% of specificity), and is a good marker for exposure in vulnerable groups [43].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study showed a prevalence of HCV infection in homeless men, higher than the general population of Brazil. Injection drug use was the main risk factor in this population. High rates of risk behaviors, drug use, inconsistent condom use, and multiple sexual partners, were found. The results of this study suggest that this population is at high risk for HCV infection, suggesting the need for effective prevention programs, including health education activities, harm reduction strategies, condom availability, and access to testing and counseling for HCV infection and other parenterally transmitted pathogens. Finally, further studies are needed to verify the actual magnitude of this infection in homeless population in Brazil.

Abbreviations

- aPR:

-

Adjusted prevalence ratio

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C Virus

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

References

Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, Brown A, Cooke GS, Pybus OG, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):77–87.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Screening, Care and Treatment of Persons with Hepatitis C Infection [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2016 Sept 10]. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/111747/1/9789241548755_eng.pdf.

Stoddard MB, Li H, Wang S, Saeed M, Andrus L, Ding W, et al. Identification, molecular cloning, and analysis of full-length hepatitis C virus transmitted/founder genotypes 1, 3, and 4. Mbio. 2015;6(2):e02518–14.

Pereira LMMB, Martelli CMT, Moreira RC, Merchan-Hamman E, Stein AT, Cardoso MRA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Hepatitis C virus infection in Brazil, 2005 through 2009: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:60.

Strehlow AJ, Robertson MJ, Zerger S, Rongey C, Arangua L, Farrell E, et al. Hepatitis C among clients of health care for the homeless primary care clinics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):811–33.

Mühlberger N, Schwarzer R, Lettmeier B, Sroczynski G, Zeuzem S, Siebert U. HCV-related burden of disease in Europe: a systematic assessment of incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:34.

May S, Ngui SL, Collins S, Lattimor S, Ramsay M, Tedder RS, Ijaz S. Molecular epidemiology of newly acquired hepatitis C infections in England 2008–2011: Genotype, phylogeny and mutation analysis. J Clin Virol. 2015;64:6–11.

World Health Organization. Prevention e Control of Viral Hepatitis Infection [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2016 Sept 10]. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/130012/1/WHO_HSE_PED_HIP_GHP_2012.1_eng.pdf.

Sherriff LC, Mayon-White RT. A survey of hepatitis C prevalence amongst the homeless community of Oxford. J Public Helth Med. 2003;25(4):358–61.

Raoult D, Foucault C, Brouqui P. Infections in the homeless. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:77–84.

Brito VOC, Parra D, Facchini R, Buchalla CM. HIV infection, hepatitis B and C and syphilis in homeless people, in the city of São Paulo. Brazil Rev Saúde Pública. 2007;41(2):47–56.

Beijer U, Wolf A, Fazel S. Prevalence of tuberculosis, hepatitis C virus, and HIV in homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:859–70.

Saeed U, Waheed Y, Ashraf M. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses: a review of viral genomes, viral induced host immune responses, genotypic distributions and worldwide epidemiology. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2014;4(2):88–96.

Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1):58–68.

Amiri FB, Gouya MM, Saifi M, Rohani M, Tabarsi P, Sedaghat A, et al. Vulnerability of Homeless People in Tehran, Iran, to HIV, Tuberculosis and Viral Hepatitis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98742.

Vahdani P, Hosseini-Moghaddam SM, Family A, Moheb-Dezfouli R, et al. Prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV, and syphilis among homeless subjects older than fifteen years in Tehran. Arch Iranian Med. 2009;12(5):483–87.

Schwarz KB, Garrett B, Alter MJ, Thompson D, Strathdee SA. Seroprevalence of HCV infection in homeless Baltimore families. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:580–7.

Noell J, Rohde P, Ochs L, Yovanoff P, Alter MJ, Schmid S, et al. Incidence and prevalence of chlamydia, herpes, and viral hepatitis in a homeless adolescent population. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(1):4–10.

Kerr T, Marshall BD, Miller C, Shannon K, Zhang R, Montaner JS, et al. Injection drug use among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:171.

Pinto VM, Tancredi MV, Alencar HDRD, Camolesi E, Holcman MM, Grecco JP, et al. Prevalência de sífilis e fatores associados a população em situação de rua de São Paulo, Brasil, com utilização de Teste Rápido. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2014;17(2):341–54.

Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Boivin JF, Cédras L, Vincelette J. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among street youths. CMAJ. 2001;165(5):557–60.

Beech BM, Myers L, Beech DJ, Kernick NS. Human immunodeficiency syndrome and hepatitis B and C infections among homeless adolescents. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2003;14:12–9.

Morano JP, Zelenev A, Lombard A, Marcus R, Gibson BA, Altice FL. Strategies for Hepatitis C Testing and Linkage to Care for Vulnerable Populations: Point-of-Care and Standard HCV Testing in a Mobile Medical Clinic. J Community Health. 2014;39(5):922–34.

Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de DST/Aids e Hepatites Virais. Manual técnico para o diagnóstico das Hepatites Virais [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Sept 12]. Available at: http://www.aids.gov.br/sites/default/files/anexos/publicacao/2015/58551/manual_tecnico_hv_pdf_75405.pdf.

Razali NM, Wah YB. Power comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling tests. J Stat Model Analytics. 2011;2(1):21–33.

Coutinho LMS, Scazufca M, Menezes P. Methods for estimating prevalence ratios in cross-sectional studies. Rev Saude Publica. 2008;42(6):992–8.

Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21.

Ministério da Saúde. Estudo de prevalência de base populacional das infecções pelos vírus das hepatites A, B e C nas capitais do Brasil [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2016 June 9]. Available at: http://www.aids.gov.br/sites/default/files/anexos/publicacao/2010/50071/estudo_prevalencia_hepatites_pdf_26830.pdf.

Lopes CLR, Teles SA, Espírito-Santo MP, Lampe E, Rodrigues FP, Motta-Castro ARC, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and genotypes of hepatitis C virus infection among drug users, Central-Western Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2009;43(Supl. 1):43–50.

Volf V, Marx D, Pliskova L, Sümegh L, Celko A. A survey of hepatitis B and C prevalence amongst the homeless community of Prague. Eur J Pub Health. 2008;18:44–7.

Stein JA. Impact of hepatitis B and C infection on health services utilization in homeless adults: a test of the gelberg-andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):20–30.

Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Arangua L, Leake BD, Sumner G, Moe A, et al. Prevalence, distribution, and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:407–21.

O’Carroll A, O’Reilly F. Health of the homeless in Dublin: has anything changed in the context of Ireland’s economic boom? Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:448–53.

Sword W, Jack S, Niccols A, Milligan K, Henderson J, Thabane L. Integrated programs for women with substance use issues and their children: a qualitative meta-synthesis of processes and outcomes. Harm Reduct J. 2009;6:32–49.

German D, Latkin CA. Social stability and HIV risk behavior: evaluating the role of accumulated vulnerability. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):168–78.

Hiller SP, Syvertsen JL, Lozada R, Ojeda VD. Social support and recovery among Mexican female sex workers who inject drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;45(1):44–54.

Qiao A, Li X, Stanton B. Social support and HIV-related risk behaviors: a systematic review of the global literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):419–41.

Nelson PK, Mathers BM, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):571–83.

Moses S, Mestery K, Kaita KD, Minuk GY. Viral hepatitis in a Canadian street-involved population. Can J Public Health. 2002;93(2):123–8.

Nyamathi A, Robbins WA, Fahey JL, Wiley D, Pekler VA, Longshore D. Presence and predictors of hepatitis C virus RNA in the semen of homeless men. Biol Res Nurs. 2002;4(1):22–30.

Terraut NA, Dodge JL, Murphy EL, Tavis JE, Kiss A, Levin TR, et al. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among monogamous heterosexual couples: The HCV partners study. Hepatology. 2013;57(3):881–9.

Shaheen MA, Idrees M. Evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis C virus disease. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(3):616–27.

Shivkumar S, Peeling R, Jafari Y, et al. Accuracy of rapid and pointof-care screening tests for hepatitis C: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:558–66.

Acknowledgements

Brian Ream edited this manuscript in English.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available of Faculty of Nursing of Federal Universty Goiás (Goiás, Brazil) and will be made easily available on request, when required.

Authors’ contributions

All of the authors participated in writing the manuscript. Data analysis was performed by RAG; study design and ethical oversight was provided by PMF and SMB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinics Hospital of Federal University of Goiás, under number 1236774. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira, P.M., Guimarães, R.A., Souza, C.M. et al. Exposure to hepatitis C virus in homeless men in Central Brazil: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 17, 90 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3952-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3952-6