Abstract

Background

Alcohol consumption during attempts at smoking cessation can provoke relapse and so smokers are often advised to restrict their alcohol consumption during this time. This study assessed at a population-level whether smokers having recently initiated an attempt to stop smoking are more likely than other smokers to report i) lower alcohol consumption and ii) trying to reduce their alcohol consumption.

Method

Cross-sectional household surveys of 6287 last-year smokers who also completed the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test consumption questionnaire (AUDIT-C). Respondents who reported attempting to quit smoking in the last week were compared with those who did not. Those with AUDIT-C≥5 were also asked if they were currently trying to reduce the amount of alcohol they consume.

Results

After adjustment for socio-demographic characteristics and current smoking status, smokers who reported a quit attempt within the last week had lower AUDIT-C scores compared with those who did not report an attempt in the last week (βadj = −0.56, 95 % CI = −1.08 to −0.04) and were less likely to be classified as higher risk (AUDIT-C≥5: ORadj = 0.57, 95 % CI = 0.38 to 0.85). The lower AUDIT-C scores appeared to be a result of lower scores on the frequency of ‘binge’ drinking item (βadj = −0.25, 95 % CI = −0.43 to −0.07), with those who reported a quit attempt within the last week compared with those who did not being less likely to binge drink at least weekly (ORadj = 0.54, 95 % CI = 0.29 to 0.999) and more likely to not binge drink at all (ORadj = 1.70, 95 % CI = 1.16 to 2.49). Among smokers with higher risk consumption (AUDIT-C≥5), those who reported an attempt to stop smoking within the last week compared with those who did not were more likely to report trying to reduce their alcohol consumption (ORadj = 2.98, 95 % CI = 1.48 to 6.01).

Conclusion

Smokers who report starting a quit attempt in the last week also report lower alcohol consumption, including less frequent binge drinking, and appear more likely to report currently attempting to reduce their alcohol consumption compared with smokers who do not report a quit attempt in the last week.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption are two of the most serious public health problems [1–4] and have a close and complex relationship [5]. There is co-morbidity such that people with an alcohol disorder are substantially more likely to smoke cigarettes [6–10]. Cross-sectional epidemiological data indicate that lifetime quit rates for smokers are lower [5–7] and nicotine dependence higher in those with an alcohol use disorder [5], while longitudinal data indicate that smokers with an alcohol use disorder are less likely to attempt and succeed in stopping [11, 12] and among former smokers, those with an alcohol use disorder appear more likely to relapse [11]. Alcohol consumption during attempts at smoking cessation is associated with greater risk of lapse and relapse [13–17] even after adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics and tobacco dependence [13]. Alcohol-related lapses also appear qualitatively distinct from lapses not involving alcohol [13]. There are variety of possible mechanisms through which alcohol consumption could increase the risk of lapse during a smoking cessation attempt (for example, reduction in self-control, increased salience of smoking cues or increased likelihood of exposure to other smoking cues; [17]), and as a consequence smokers are advised to restrict their alcohol consumption during an attempt to stop [13, 18, 19].

This position is supported by the wider multiple health behaviour change literature. The field of multiple behaviour change is motivated by findings that many health behaviours tend to cluster and often result in synergistic effects on mortality and morbidity [20, 21]. In theory this presents a cost-effective opportunity to target particularly at-risk groups and intervene on several public health problems simultaneously. In practice, multiple behaviour change has proved a considerable challenge [22, 23]. While generalisable results are scarce, a recent theoretically-guided meta-analysis of behaviour change interventions indicated that there may be a curvilinear relation between the number of behavioural recommendations and outcome, with a moderate (2–3) number producing the greatest effect [24].

It is unclear at a population-level whether smokers follow advice to restrict alcohol during a quit attempt. One indicator would be the association between a recent attempt to stop smoking and alcohol consumption. It is not possible with cross-sectional epidemiological data to rule out the possibility that any association could be explained by people with lower alcohol consumption being more likely to attempt to quit smoking. However, the association is important whichever the direction of causality; and this alternative may suggest the need for smokers with higher alcohol consumption to be encouraged to quit smoking. To help tease apart the issue, it is also instructive to assess whether among smokers with higher-risk alcohol consumption there is an association between a recent attempt to quit smoking and a current attempt to cut down alcohol consumption.

This study sought to address the following research questions: What is the association among smokers in England between a recent attempt to quit smoking and alcohol consumption? What is the association among smokers with higher risk alcohol consumption in England between a recent attempt to stop smoking and a current attempt to cut down on their drinking?

Methods

Study design

Data were collected using repeated cross-sectional household surveys of representative samples of the population of adults in England conducted in consecutive monthly waves between March 2014 and September 2015. The surveys are part of the ongoing Smoking Toolkit Study (STS) and Alcohol Toolkit Study (ATS) which are designed to provide tracking information about smoking, alcohol consumption and related behaviours in England [25, 26]. Each month a new sample of approximately 1700 adults aged 16 and over complete a face-to-face computer-assisted survey. The sampling is a hybrid between random probability and simple quota and the method has been shown to result in a sample that is nationally representative in its socio-demographic composition [25].

Study population

We used data from respondents aged 16 and over in the period from March 2014 to September 2015 who reported smoking tobacco in the last year by endorsing one of the first four options on the following question: ‘Which of the following best applies to you? Please note cigarettes refer to tobacco and not electronic cigarettes.’: (i) ‘I smoke cigarettes (including hand-rolled) everyday’; (ii) ‘I smoke cigarettes (including hand-rolled) but not every day’; (iii) ‘I do not smoke cigarettes at all but I do smoke tobacco of some kind (e.g., pipe or cigar)’; (iv) I have stopped smoking completely in the last year’; (v) I stopped smoking completely more than a year ago; (vi) I have never been a smoker (i.e., smoked for a year or more).

Measures

Alcohol consumption was assessed by the first three consumption questions on the widely validated Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C; [27]). The AUDIT-C is the short-form of the ten-item AUDIT questionnaire and provides a score ranging between 0 and 12 (with 0 indicating non-drinkers). For the current study, higher risk consumption was indicated by a score ≥ 5 [28]. The three component items of the AUDIT-C consist of ‘drinking frequency’ (0–4), ‘typical quantity per occasion’ (0–4), and ‘high intensity or ‘binge’ drinking frequency’ (0–4). From the binge drinking item, categorical measures were derived of those who did not binge drink compared with those who did, and those who did binge drink at least weekly compared with those who did not. Smokers whose consumption of alcohol was classified as higher risk, were also asked whether they were currently attempting to restrict their alcohol consumption.

All smokers were asked whether they had made a serious attempt to stop smoking and those who had made an attempt were asked how recently. Smokers were classified into those who attempted to stop in the last week and those who had not. Respondents were also asked questions that assessed: age; sex; an occupationally-based classification of socio-economic status called ‘social grade’ (dichotomised to ABC1 = higher and intermediate professional/managerial and supervisory, clerical, junior managerial/administrative/professional or C2DE = skilled, semi-skilled, unskilled manual and lowest grade workers or unemployed); government office region in England (dichotomised to North = North East, North West, and Yorkshire and the Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, or South = East of England, London, South East, and South West, classified according to an established North-South divide [29]); receipt of a voluntary educational qualification (obtained after compulsory education ceases at 16 years old); ethnicity; and disability.

Analysis

To examine associations between indices of alcohol consumption and a recent attempt to quit smoking, we first constructed unadjusted regression models in which we regressed i) indices of alcohol consumption onto a recent attempt to quit smoking (reference: no attempt to quit within the last week). We used linear regression models for the continuous dependent variables (scores on the AUDIT-C, and scores on the component items ‘drinking frequency’, ‘typical quantity per occasion’, and ‘binge frequency’) and logistic regression for the binary dependent variables (proportion classified as high risk AUDIT-C, binge drinking at least weekly, and no binge drinking). To examine the independent association after adjustment with each dependent variable, we then constructed multivariable regression models including also the socio-demographic and smoking variables listed in Table 1 (age, sex, social grade, region, receipt of a voluntary educational qualification, ethnicity, disability and current smoking status) and the survey wave. In a final subgroup analysis, to examine associations between a recent attempt to stop smoking and a current attempt to cut down drinking among smokers with higher risk alcohol consumption, we first constructed an unadjusted logistic regression model in which we regressed a current attempt to cut down drinking onto a recent attempt to quit smoking (reference: no attempt to quit within the last week). To examine the independent association after adjustment, we constructed a multivariable logistic regression model including also the socio-demographic variables listed in Table 1 and the survey wave.

Results

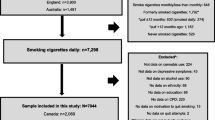

A total of 31,878 adults in England were surveyed between March 2014 and September 2015, of whom 6652 (20.9 %) reported smoking in the last year and 6287 (94.5 %) of these smokers also provided complete data on all variables. The overall socio-demographic characteristics of the sample (see Table 1) were broadly representative of smokers: the sample was younger and contained a lower proportion of women and greater proportion of people with lower social grade and no post-16 qualifications than would be expected in a general population sample [25]. A total of 144 of these smokers reported that they had attempted to quit smoking in the last week. There was no evidence of association between recent quitting and socio-demographic characteristics but, as expected, those last-year smokers who had attempted to quit in the last week were much more likely to report currently not smoking than those who had not attempted to quit within the last week (see Table 1).

In an unadjusted model, smokers who had attempted to quit within the last week reported lower AUDIT-C scores than those who had not: scores were 0.66 points (95 % CI = 1.21 to 0.11) lower on average among those who had attempted to quit in the last week (see Table 2). This result was largely unchanged after adjustment for age, sex, social grade, region, voluntary educational qualification, ethnicity, disability, current smoking status and survey wave: the adjusted AUDIT-C score was 0.56 points (95 % CI = −1.08 to −0.04) lower among those who had attempted to quit in the last week (see Table 2). In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, those smokers who had attempted to quit in the last week were also less likely to be classified as higher risk drinkers (AUDIT-C≥5, see Table 2).

The lower AUDIT-C scores among those who attempted to quit smoking in the last week appeared to be a result of lower scores on the component item [question 3] frequency of binge drinking (see Table 2), with those who begun a quit attempt in the last week being less likely to binge drink at least weekly and more likely to not binge drink at all (see Table 2). There was, however, no evidence of association between a recent attempt to quit smoking and the drinking frequency or typical quantity per occasion AUDIT-C items (see Table 2). In all these analyses, the results were broadly unchanged after adjustment (see Table 2).

The final subgroup analysis included only those smokers whose alcohol consumption was classified as higher risk (n = 2266). Compared with smokers who had not, those who had attempted to stop smoking within the last week were more likely to report also currently trying to restrict their alcohol consumption in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (see Table 2).

Discussion

This study found that smokers who reported attempting to stop within the last week had lower levels of alcohol consumption, especially bingeing, and were less likely to be classified as having higher risk alcohol consumption (AUDIT-C ≥5) compared with those who did not report an attempt to quit smoking in the last week. Among those with higher risk alcohol consumption, smokers who reported attempting to stop smoking within the last week compared with those who reported no attempt were more likely to report also currently trying to restrict their alcohol consumption.

This study adds to the literature on the close relationship between smoking and alcohol consumption [5]. One component of the relationship is that alcohol consumption is associated with lapse and relapse to smoking [13–17], which has resulted in smokers being widely advised to restrict their consumption during quit attempts [13, 18, 19]. In the current study, the association between a recent attempt to quit smoking and reduced alcohol consumption indicates that smokers in England may be following this best-practice advice to restrict their alcohol consumption during a smoking cessation attempt. It is not possible with cross-sectional epidemiological data to rule out reverse causation i.e., the possibility that the association between quitting and consumption may actually be driven by people with lower alcohol consumption being more likely to attempt to quit smoking. If this were the explanation, the association would remain important because it would suggest the need for smokers with higher alcohol consumption to be targeted for further encouragement to attempt to quit smoking. However, another finding in this study indicates that the association is unlikely to be driven exclusively by lighter drinkers being more likely to attempt quit smoking: among smokers who were also heavier drinkers, those who had made an attempt to quit smoking within the last week compared with those who had not were also more likely to report a current attempt to restrict their alcohol consumption. The present study cannot determine whether attempts to quit smoking tend to precede attempts to restrict alcohol consumption, or vice versa.

These findings have possible implications for policy evaluation and development: there appears to be a need for greater attention to possible crossover effects when evaluating the cost-effectiveness of alcohol and tobacco interventions and more reason for a coordinated strategy on alcohol and tobacco control. Policy on brief intervention by health professionals is one example. Brief intervention for smoking and alcohol are both effective and cost-effective interventions [30–34]. Delivery of smoking brief intervention is much more common in England than is alcohol [35], and there is a need to increase the rate of screening and brief intervention on alcohol [36, 37]. The current study suggests that smokers may be more likely to reduce their alcohol consumption when attempting to stop smoking than when they are not. While these findings cannot speak to the effectiveness of brief interventions, they do suggest that a smoking brief intervention may be a good opportunity to intervene also on alcohol: smokers may be likely to plan to reduce their alcohol consumption regardless and may therefore be particularly receptive to intervention on alcohol. However, this is an empirical question for which there is currently sparse experimental evidence [38–40], and until such evidence is forthcoming, other strategies to increase alcohol brief intervention may warrant greater resource [41–45]. In the meantime, the current findings could be simply disseminated to health professionals to reassure them that many smokers may be planning to cut down on their drinking anyway and their intervention on alcohol may be therefore unlikely to compromise the patient relationship: the GP-patient relationship is a regularly cited barrier to a greater rate of brief intervention, albeit one of several including inadequate training, and lack of time or financial incentives [46–52].

There are three important limitations of this study. The limitation on interpretation of cross-sectional design in relation to direction of causation has been discussed. A second limitation is that as an observational study it is possible that unmeasured confounding could have influenced the results. For example, it is possible that the diagnosis of a health problem led to attempts to cut down on both drinking and smoking (i.e., cross-behavioural sick-quitter effects). Our adjustment for a self-reported disability may not have sufficiently accounted for this possibility. Another limitation is that the study relied on self-reported data with the risk of socially desirable responding. However, in population surveys the social pressure and related misreporting of smoking is low and it is generally considered acceptable to rely on self-reported data [53], while we used an abbreviated version of a high quality tool that has been widely validated to assess alcohol use disorder (AUDIT-C; [27, 54]). The full version of the AUDIT questionnaire is more widely validated but includes questions across a longer reference period that would have rendered the scale less sensitive to recent changes, while AUDIT-C has good validity, excellent reliability and responsiveness to change [54].

Conclusions

In conclusion, smokers who report a recent attempt to stop are more likely to report lower-risk alcohol consumption, including less frequent binge drinking, after adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics. Among smokers with higher-risk alcohol consumption, those who report a last week attempt to stop are more likely to report also a current attempt to cut down on their drinking.

References

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, AlMazroa MA, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–60.

UK Department of Health. The Cost of Alcohol Harm to the NHS in England. An Update to the Cabinet Office (2003) Study. London: UK Department of Health; 2008.

UK Department of Health. Healthy Lives, Healthy People: a tobacco control plan for England. London: UK Department of Health; 2011.

Carter BD, Abnet CC, Feskanich D, Freedman ND, Hartge P, Lewis CE, Ockene JK, Prentice RL, Speizer FE, Thun MJ, Jacobs EJ. Smoking and mortality — beyond established causes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:631–40.

Hughes JR, Kalman D. Do smokers with alcohol problems have more difficulty quitting? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:91–102.

Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–10.

Kalman D, Morissette SB, George TP. Co-morbidity of smoking in patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2005;14:106–23.

Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:162–71.

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27.

Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–42.

Weinberger AH, Pilver CE, Hoff RA, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Changes in smoking for adults with and without alcohol and drug use disorders: longitudinal evaluation in the U.S. population. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39:186–93.

Leeman RF, McKee SA, Toll BA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cooney JL, Makuch RW, O'Malley SS. Risk factors for treatment failure in smokers: relationship to alcohol use and to lifetime history of an alcohol use disorder. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1793–809.

Kahler CW, Spillane NS, Metrik J. Alcohol use and initial smoking lapses among heavy drinkers in smoking cessation treatment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:781–5.

Brandon TH, Tiffany ST, Obremski KM, Baker TB. Postcessation cigarette use: the process of relapse. Addict Behav. 1990;15:105–14.

Shiffman S. Relapse following smoking cessation: a situational analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50:71–86.

Borland R. Slip-ups and relapse in attempts to quit smoking. Addict Behav. 1990;15:235–45.

Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JA, Hickcox M. First lapses to smoking: within-subjects analysis of real-time reports. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:366–79.

Gulliver SB, Kamholz BW, Helstrom AW. Smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence: what do the data tell us? Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:208–12.

Friend KB, Pagano ME. Smoking cessation and alcohol consumption in individuals in treatment for alcohol use disorders. J Addict Dis. 2005;24:61–75.

Kvaavik E, Batty GD, Ursin G, Huxley R, Gale CR. Influence of individual and combined health behaviors on total and cause-specific mortality in men and women: the United Kingdom health and lifestyle survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:711–8.

Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Day N. Combined impact of health behaviours and mortality in men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e12.

Evers K, Quintiliani L. Advances in multiple health behavior change research. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3:59–61.

Spring B, Moller AC, Coons MJ. Multiple health behaviours: overview and implications. J Public Health (Oxf). 2012;34:i3–i10.

Wilson K, Senay I, Durantini M, Sanchez F, Hennessy M, Spring B, Albarracin D. When it comes to lifestyle recommendations, more is sometimes less: a meta-analysis of theoretical assumptions underlying the effectiveness of interventions promoting multiple behavior domain change. Psychol Bull. 2015;141:474–509.

Fidler JA, Shahab L, West O, Jarvis MJ, McEwen A, Stapleton JA, Vangeli E, West R. 'The smoking toolkit study': a national study of smoking and smoking cessation in England. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:479.

Beard E, Brown J, West R, Acton C, Brennan A, Drummond C, Hickman M, Holmes J, Kaner EF, Lock K, et al. Protocol for a national monthly survey of alcohol use in England with 6-month follow-up: ‘the Alcohol Toolkit Study’. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:230.

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary care (second edition). Geneva: WHO; 2001.

Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1208–17.

Hacking JM, Muller S, Buchan IE. Trends in mortality from 1965 to 2008 across the English north-south divide: comparative observational study. BMJ. 2011;342:d508.

Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, West R. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012;107:1066–73.

Purshouse RC, Brennan A, Rafia R, Latimer NR, Archer RJ, Angus CR, Preston LR, Meier PS. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief interventions in primary care in England. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48:180–8.

Angus C, Latimer N, Preston L, Li J, Purshouse R. What are the implications for policy makers? A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of screening and brief interventions for alcohol misuse in primary care. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:114.

Kaner E, Beyer F, Dickinson H, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, Heather N, Saunders J, Burnand B. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD004148.

Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD000165.

Brown J, West R, Angus CR, Beard E, Brennan A, Drummond C, Hickman M, Holmes J, Kaner EF, Michie S. Comparison of brief interventions in primary care on smoking and excessive alcohol consumption in England: a population survey. Br J Gen Pract. In press. 2016;66:e1-e9.

UK Home Office. The Government’s Alcohol Strategy. London: The Stationary Office; 2012.

Alcohol Health Alliance UK. Health first: an evidence-based alcohol strategy for the UK. Stirling: University of Stirling; 2013.

McRee B, Babor T, Del Boca F, Vendetti J, Oncken C, Bailit H, Burleson J. Screening and brief intervention for patients with tobacco and at-risk alcohol use in a dental setting. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:A19.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K, Puckpinyo A, Viripiromgool S, Thamma-aphiphol K, Suthisukhon K, Dumee D, Kongtapan T. Screening and concurrent brief intervention of conjoint hazardous or harmful alcohol and tobacco use in hospital out-patients in Thailand: a randomized controlled trial. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10:22.

Prochaska JJ, Prochaska JO. A Review of Multiple Health Behavior Change Interventions for Primary Prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5. doi: 10.1177/1559827610391883.

Hamilton FL, Laverty AA, Gluvajic D, Huckvale K, Car J, Majeed A, Millett C. Effect of financial incentives on delivery of alcohol screening and brief intervention (ASBI) in primary care: longitudinal study. J Public Health (Oxf). 2014;36:450–9.

Lapham GT, Achtmeyer CE, Williams EC, Hawkins EJ, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Increased documented brief alcohol interventions with a performance measure and electronic decision support. Med Care. 2012;50:179–87.

Michaud P, Fouilland P, Dewost AV, Abesdris J, de Rohan S, Toubal S, Gremy I, Fauvel G, Heather N. Early screening and brief intervention among excessive alcohol users: mobilizing general practitioners in an efficient way. Rev Prat. 2007;57:1219–26.

Angus C, Li J, Parrott S, Brennan A. Optimizing Delivery of Health Care Interventions (ODHIN): Cost-Effectiveness – Analysis of the WP5 Trial. University of Sheffield; 2014. http://www.odhinproject.eu/resources/documents/doc_download/119-addendum-to-d3-1-cost-effectiveness-analysis-of-the-wp5-trial.htmlURL: Please check that the following URLs are working. If not, please provide alternatives: http://www.odhinproject.eu/resources/documents/doc_download/119-addendum-to-d3-1-cost-effectiveness-analysis-of-the-wp5-trial.htmlhttp://www.odhinproject.eu/resources/documents/doc_download/119-addendum-to-d3-1-cost-effectiveness-analysis-of-the-wp5-trial.htmlYes - it works, it leads directly to a pdf download.. Accessed 01.02.2015.

Keurhorst M, van de Glind I, Bitarello do Amaral-Sabadini M, Anderson P, Kaner E, Newbury-Birch D, Braspenning J, Wensing M, Heinen M, Laurant M. Implementation strategies to enhance management of heavy alcohol consumption in primary health care: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2015;110:1877–900.

Anderson P, Kaner E, Wutzke S, Funk M, Heather N, Wensing M, Grol R, Gual A, Pas L. Attitudes and managing alcohol problems in general practice: an interaction analysis based on findings from a WHO collaborative study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39(4):351-6.

Heather N, Dallolio E, Hutchings D, Kaner E, White M. Implementing routine screening and brief alcohol intervention in primary health care: a Delphi survey of expert opinion. J Subst Use. 2004;9:68–85.

Hutchings D, Cassidy P, Dallolio E, Pearson P, Heather N, Kaner E. Implementing screening and brief alcohol interventions in primary care: views from both sides of the consultation. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2006;7:221–9.

Johnson M, Jackson R, Guillaume L, Meier P, Goyder E. Barriers and facilitators to implementing screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33:412–21.

McAvoy BR, Donovan RJ, Jalleh G, Saunders JB, Wutzke SE, Lee N, Kaner EF, Heather N, McCormick R, Barfod S, Gache P. General Practitioners, Prevention and Alcohol - a powerful cocktail? Facilitators and inhibitors of practising preventive medicine in general and early intervention for alcohol in particular: a 12-nation key informant and general practitioner study. Drugs. 2001;8:103–17.

Rapley T, May C, Frances Kaner E. Still a difficult business? Negotiating alcohol-related problems in general practice consultations. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2418–28.

Wilson GB, Lock CA, Heather N, Cassidy P, Christie MM, Kaner EF. Intervention against excessive alcohol consumption in primary health care: a survey of GPs' attitudes and practices in England 10 years on. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:570–7.

Wong SL, Shields M, Leatherdale S, Malaison E, Hammond D. Assessment of validity of self-reported smoking status. Health Rep. 2012;23:47–53.

Bradley KA, McDonell MB, Bush K, Kivlahan DR, Diehr P, Fihn SD. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1842–9.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all funding.

Funding

Funding was provided for the conduct of this research and preparation of the manuscript. The funders had no final role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. All decisions taken by the investigators were unrestricted. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (SPHR) primarily funded data collection for the Alcohol Toolkit Study (SPHR-SWP-ALC-WP5); Cancer Research UK primarily funded data collection for the Smoking Toolkit Study (C1417/A14135; C36048/A11654; C44576/A19501). SPHR is a partnership between the Universities of Sheffield; Bristol; Cambridge; Exeter; UCL; The London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; the LiLaC collaboration between the Universities of Liverpool and Lancaster and Fuse; The Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, a collaboration between Newcastle, Durham, Northumbria, Sunderland and Teesside Universities. We also acknowledge the Department of Health, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Johnson & Johnson have all funded data collection previously for the Smoking Toolkit Study. Jamie Brown’s post is funded by a fellowship from the Society for the Study of Addiction and CRUK also provide support (C1417/A14135); Robert West is funded by Cancer Research UK (C1417/A14135); Duncan Gillespie’s post is funded by UKCTAS; Emma Beard, Alan Brennan, Matthew Hickman, John Holmes, Eileen Kaner, and Susan Michie have all received funding from the NIHR SPHR; Colin Drummond was part funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London. The views expressed are those of the authors(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or Department of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

JB, RW & SM conceived of the design of the current study. JB performed the data analysis and interpretation. JB drafted the paper and all other authors provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Competing interests

JB & EB have received unrestricted research grants from Pfizer; RW undertakes research and consultancy and receives fees for speaking from companies that develop and manufacture smoking cessation medications (Pfizer, J&J, McNeil, GSK, Nabi, Novartis, and Sanofi-Aventis); there are no other financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years and there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the STS was originally granted by the UCL Ethics Committee (ID 0498/001) and approval for the ATS was granted by the same committee as an extension of the STS. All respondents provided informed verbal consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, J., West, R., Beard, E. et al. Are recent attempts to quit smoking associated with reduced drinking in England? A cross-sectional population survey. BMC Public Health 16, 535 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3223-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3223-6