Abstract

Background

There are evidence-based interventions for depression that include different components. However, the efficacy of their therapeutic components is unknown. Another important issue related to depression interventions is that, up to now, their therapeutic components have only focused on reducing negative symptoms rather than on improving positive affect and well-being. Because the low levels of positive affect are more strongly linked to depression than to other emotional disorders, it is important to include this variable as an important treatment target. Positive psychotherapeutic strategies (PPs) could help in this issue. The results obtained so far are consistent and promising, showing that Internet-based interventions are effective in treating depression. However, most of them are also multi-component, and it is important to make progress in investigating what each component contributes to the intervention.

Methods

The current study will be a three-armed, simple-blinded, randomized controlled clinical trial with a dismantling design. 192 participants will be randomly assigned to: a) an Internet-based Global Protocol condition, which includes traditional therapeutic components of evidence-based treatments for depression (Motivation for change, Psychoeducation, Cognitive Therapy, Behavioral Activation (BA), Relapse Prevention) and PPs component, offering strategies to enhance positive mood and promote psychological strengths; b) an Internet-based BA Protocol condition (without the PPs component), and c) an Internet-based PPs Protocol condition (without the BA component). Primary outcome measures will be the BDI-II and PANAS. Secondary outcomes will include other variables such as depression, anxiety and stress, quality of life, resilience, and wellbeing related measures. Treatment acceptance and usability will also be measured. Participants will be assessed at pre-, post-treatment, 3-, 6- and 12- month follow- ups. The data will be analyzed based on the Intention-to-treat principle. Per protocol analyses will also be performed.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized dismantling intervention study for depression with the aim of exploring the contribution of a PPs component and the BA component in an Internet-based intervention. The three protocols are online interventions, helping to reach many people who need psychological treatments and otherwise would not have access to them.

Trial registration

Clinicalstrials.gov as NCT03159715. Registered 19 May 2017.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Major depression is projected to become the largest contributor to the disease burden in high income nations by 2030 [1, 2]. Hundreds of controlled and comparative studies have examined the efficacy of psychological treatments for depression [3, 4]. Thus, we have evidence-based interventions for depression, including cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) [5, 6] and behavioral activation (BA) [7, 8], as well as interpersonal [3, 9] or problem-solving therapy [10]. Of all of them, CBT has been extensively researched as an intervention for patients with depression. Studies have shown robust evidence of its efficacy [3, 11,12,13]. Furthermore, the effect sizes found for CBT have been large compared to waiting list, placebo, or no-treatment conditions [14]. It usually consists of applied cognitive techniques to change thought patterns and behavioral techniques to activate behaviors [13]. However, the efficacy of its therapeutic components is unknown [15]. The literature shows that BA is an essential component of CBT treatments for depression [16,17,18]. Meta-analyses show that the effects of BA treatment on depressive symptoms are maintained or even improve at 6- and 12-month follow-ups, compared to control conditions and other treatments [7]. Nevertheless, less is known about how depression therapies work and the mechanisms that are responsible for their effects [19, 20]. The US Institute of Medicine indicated that a key step in being able to offer evidence-based interventions in clinical settings is the identification of the core elements of psychological interventions [21]. It has been pointed out that component studies are the best design to examine these core elements [15].

Another important issue related to depression interventions is that, until recently, their therapeutic components focused solely on improving negative symptoms (depressive symptoms, anxiety, etc.), and not on the promotion of positive affect, well-being, and character strengths [22]. Positive psychotherapeutic strategies (PPs) work to help in this issue by promoting positive functioning [22]. The main PPs are Well-being Therapy [23,24,25,26], which improves well-being dimensions based on Ryff’s model of eudaimonic well-being [27]; Quality of Life therapy [28, 29], which is more focused on promoting hedonic well-being and life satisfaction in various significant life domains; and Positive Psychotherapy [30, 31], focused on alleviating suffering and systematically enhance happiness by building positive emotions, strengths, and meaning in patients’ lives; and Strengths based Counseling [32, 33]. These interventions have been tested in clinical populations, particularly in depressed patients [34, 35]. They are effective in the improvement of depression and well-being [36, 37]. It has been established in the literature that depressive symptoms are related to lack of meaning in life and low levels of positive emotions, and that depression is more associated with low levels of positive affect than other emotional disorders [38]. Most of the positive interventions promote positive affect, gratitude, resilience, and positive functioning [22], and different studies have pointed out the importance of taking these variables into account as important depression intervention targets [39, 40].

Because depression is a prevalent mental disorder, one of the principal challenges nowadays is to develop new ways to deliver psychological interventions in order to maximize their efficiency and dissemination [41, 42]. Several internationally well-known research groups have launched Internet-based programs in an attempt to address this issue. Results obtained so far show that these online programs are effective in treating depression [3, 43,44,45,46,47]. However, as in the case of face-to-face interventions, most of the Internet-based intervention programs for depression are also multi-component, and it is important to make progress in investigating what each component brings to the intervention.

As mentioned above, component studies are an important tool for examining how therapies work, and they provide an appropriate way to identify the active elements of interventions [48]. With this study design, multicomponent treatments are decomposed, and the complete intervention is compared to an intervention in which a component is eliminated (dismantling studies) or to an intervention with an addition component (additive studies; [49]). There are few studies with a dismantling design in interventions for depression [50]. A recent comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of dismantling studies of psychotherapies for adult depression included only 16 studies, none with an Internet-based intervention [15].

Our research group has developed an Internet-based cognitive-behavioral treatment protocol that also includes PPs for patients suffering from depressive symptoms. It has shown its efficacy in different RCTs [51,52,53]. The results show that this intervention is effective overall, but we do not know the specific contribution of each of its therapeutic components. Using a dismantling strategy could help to identify the contribution of BA and PPs (its main therapeutic components) to the therapeutic change. As a result, this information can contribute to improving intervention programs for depression.

To the best of our knowledge no study with a dismantling design exists with an Internet-based treatment protocol for depression, and even less so with the specific objective of discovering the contribution of BA and PPs.

The objectives of the current study are to (a) evaluate the efficacy at post-treatment and follow-ups (3, 6, and 12 months) of a complete Internet-based protocol for depressive symptoms (including motivation, cognitive restructuring, BA, PPs, Relapse prevention), a protocol for depressive symptoms without PPs, and a protocol for depressive symptoms without a BA component, all of them administered through the Internet to patients with mild to moderate depressive symptoms; (b) analyze the mediators of change in depressive symptoms; and (c) study the acceptability and usability of the intervention.

Methods/design

Study design

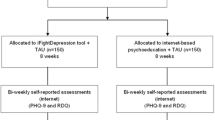

The current study will be a three-armed, simple-blinded, randomized controlled clinical trial with a dismantling design. Specifically, three groups will be compared: a) an Internet-based Global Protocol condition (IGc), b) an Internet-based BA Protocol condition (IBAc), and c) an Internet-based PPs Protocol condition (IPPc). At this moment, the study is ongoing, and we are in the participant recruitment phase. Participants will be randomly allocated to one of the three experimental conditions.

Randomization will be stratified by levels of depression severity (mild to moderate).

We will carry out block randomization within each stratum to certify that all levels of depression are balanced across the three experimental conditions. The study follows the CONSORT statement (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) [54, 55], CONSORT-EHEALTH [56] and SPIRIT guidelines (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) [57, 58]. Participants’ assessments will be performed at pre-treatment and post-treatment. Furthermore, there will be three follow-ups: at 3, 6, and 12 months. Figure 1 shows the study flowchart.

Participants, recruitment and eligibility criteria

The RCT will be carried out at the Emotional Disorder Clinic in Universitat Jaume I. Participants will be adult volunteers with mild to moderate depressive symptoms (from 14 to 28 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II, BDI-II) [59].

Participants will be recruited through the website specially developed for this aim, emails, phone calls, or personal visits, and they will be attended to by a clinician. Once a potential participant has been identified by the clinical psychologist, s/he will be informed about all the characteristics of the study. Any questions or doubts will be clarified in order to ensure that participants have understood all the information correctly. Those who are interested in participating will sign the informed consent. Furthermore, an independent researcher will assess whether they meet all the inclusion criteria.

To participate in the study, participants must meet these inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria are: a) 18 to 65 years old; b) able to read and understand Spanish; c) access to Internet; d) knowing how to use the Internet; and e) experiencing mild to moderate depressive symptoms (from 14 to 28 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II [BDI-II]). Exclusion criteria include: a) receiving a psychological intervention; b) suffering from a severe Axis I mental disorder: alcohol and/or substance dependence disorder, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, or dementia; c) having ideation or a significant plan for suicide (assessed by the MINI and item 9 of the BDI-II). Receiving pharmacological medication while participating in the study is not an exclusion criterion. However if the patient has an increase in the pharmacological treatment, s/he will be excluded from the study analysis. Nevertheless, a reduction in the medication does not imply exclusion from the study. We will offer alternative treatments to the participants who do not meet the criteria for the present study.

If the participants fulfill the eligibility criteria, they will be randomized to one of the three experimental conditions by an independent investigator who will not have information about the RCT’s characteristics. Randomization will be performed using a weighted random number sequence generated by a computer, in order to have a homogeneous distribution across the three conditions. The study researchers will be informed about the allocation schedule via telephone call. Before the allocation to one of the three interventions, the patients will agree to participate without having the information about which intervention they will be receive. Nevertheless, for pragmatic reasons, researchers and patients will not be blind to the intervention conditions. At any time during the study, the participants will be allowed to drop out of the intervention without giving any reasons.

Ethics

This study will be carried out in conformity with the study protocol and the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, it will guarantee the confidentiality and security of the data following the guidelines set forth in the current laws and data protection regulations: The General Data Protection Regulation, agreed upon by the European Parliament and Council in April 2016. Moreover, all important EU legislation and international documents on privacy will be followed.

All participants will be volunteers. When the study has been explained to them, they will sign the online informed consent to participate. Qualified clinical personnel will conduct the clinical assessment of the participants as part as the recruitment process. In the same way, all the tasks involving the participants will be performed by qualified, expert professionals (Clinical Psychology PhD). The assessment protocol is composed of standardized instruments (semi-structured interviews and questionnaires). Likewise, treatment protocols are based on empirically-validated treatments from the Task Force on the Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures of the American Psychological Association [60].

Data protection is an important aspect of the project. To access the Internet platform, the participants will have a unique username and password combination. Furthermore, the platform will be available on a 24/7 basis. Moreover, the transferred data will be secured using AES encryption (AES-256; Advanced Encryption Standard).

The study policies do not differ from those used in other clinical trials focused on the treatment of depression through the Internet, and so no special difficulties are expected.

The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of University Jaume I (Castellon, Spain, approval number: 4/2017). The trial is registered at clinicalstrials.gov as NCT03159715.

Important protocol modifications will be communicated to relevant parties (i.e., trial participants, trial registries, journals, ethical committee and researchers).

Interventions

Internet-based global protocol condition (IGc)

We have developed a manualized intervention protocol for depressive symptoms called Sonreír es Divertido (Smiling is Fun in English). It is an Internet-based program developed in a European project: Online predictive tools for intervention in mental illness [51]. Smiling is Fun includes the psychological treatment components that are traditionally incorporated in evidence-based interventions for depression: Motivation for change, Psychoeducation, Cognitive Therapy, BA, and Relapse Prevention. The program also incorporates a PPs component, offering tools to improve positive affect and promote strengths.

The intervention program includes eight modules: four CBT based modules; three PPs based modules, and one Relapse prevention module.

Regarding the CBT modules: 1) “Motivation for change”, 2) “Understanding emotional problems”, 3) “Learning to move on”, and 4) “Learning to be flexible”, their main objectives, respectively, are: a) To analyze both the advantages and disadvantages of changing their behaviors, feelings, and thoughts; b) To offer information to help the patient to understand the characteristics of the emotional problems; c) To explain the importance of being involved in life and acquiring an appropriate activity level; and d) To teach the patients how to think in a more flexible manner.

In the case of the PPs modules, designed to promote positive affect, well-being, and psychological strengths: 5) “Learning to enjoy”, 6) “Learning to live”, 7) “Living and learning”, their principal objectives are, respectively: a) To “savor” and enjoy positive life experiences; b) To do activities linked to their own goals and values and learn how to identify their psychological strengths; c) To know how to improve their psychological strengths and start working toward the future.

At the end of the program, there is a Relapse prevention component in module 8) “From now on, what else…?”, whose objectives are: a) To review what has been learned in each module; b) To learn that finishing the program does not mean no longer practicing the strategies learned, and that it is the beginning of each patient’s path; and d) To invite them to think about what they would like their future life to be like.

Internet-based BA protocol condition (IBAc)

This intervention protocol has these CBT components from the original protocol (IGc) explained above: Motivation for change, Psychoeducation, Cognitive Flexibility, BA, and Relapse Prevention. The PPs component is not included in this protocol.

The BA component in this protocol teaches the same things as the BA component in IGc.

Internet-based PPs protocol condition (IPPc)

This intervention protocol has these CBT components from the original protocol (IGc) explained above: Motivation for change, Psychoeducation, Cognitive Flexibility, and Relapse Prevention. The BA component is not included in this protocol.

The PPs component in this protocol teaches the same things as the PPs component in IGc.

Table 1 showed the structure of the IBAc and IPPc.

It is important to mention that the three protocols have the same number of modules (eight) and a similar number of words: IGc: 35.123; IBAc 35.492 and IPPc: 39.002 (M: 36541; SD: 2139.003).

The three treatment protocols include a “Welcome” module that explains information about the treatment protocol and its purposes. Furthermore, it explains the main recommendations for obtaining the most benefit from it. After this “Welcome” module, the patients access the pre-treatment assessment online questionnaires. After the pre-treatment assessment, participants start the intervention modules. Table 2 shows the structure of each module. The modules include exercises to practice each technique and skill. Furthermore, at the end of each module, there is a post-module assessment to evaluate depression, anxiety, and positive/negative affect. When participants complete the eight treatment modules, they perform the post-treatment assessment, which is also integrated in the web system (the same self-report questionnaires as in the pre-treatment assessment, plus the treatment satisfaction scale).

An important function of the program is that the therapists have access to all the information participants provide during the treatment, so that if the patient’s condition gets worse they can receive an alert. These alerts are generated by the system when a high risk of suicide is detected. Then, an email is sent to the clinical team so that the therapist can contact the patients and make better decisions to protect and help them.

Regarding the use of the intervention, participants will progress sequentially through the program at their own rhythm, but they will be informed that they will receive the most benefit from the intervention if they do about one module every 2 weeks. This is the time stipulated to complete each module and practice the techniques and strategies learned. The participants will be informed that they have a maximum of 16 weeks to complete all eight modules. As the intervention progresses, when they finish one module, they will be allowed to look it over again if they so desire.

All the modules will be on a web platform developed by our research group (https://www.psicologiaytecnologia.com/). It was designed for optimal use on a tablet or a PC and to optimize the understanding of the modules’ content using different multimedia elements such as audio, vignettes, video, etc. The web platform has different transversal tools that accompany the person throughout the entire intervention process (Table 3).

Support

In the intervention conditions, the participants will receive human and ICT support.

Regarding human support, one trained predoctoral student in our group will make several brief phone calls at four points in time:

-

(a)

An initial telephone session: to explain the characteristics of the RCT to the participant and administer the clinical diagnostic interview and find out whether s/he fulfills the inclusion criteria.

-

(b)

An initial phone call in the “Welcome” module: encouraging patients to start the program, do one module every 2 weeks, and do the homework tasks in each module. This phone call will take place when the participants do the pre-treatment assessments.

-

(c)

One brief phone call (maximum of 10 min) when the participants reach the mid-point of the intervention (module 4): 1) to ask the participants about any doubts or difficulties regarding the use of the program and help them; 2) to remind them that they can review the content of each module; 3) to emphasize the importance of doing the tasks in each module and practice the strategies they learn; 4) to motivate patients to continue with the program and positively reinforce them for engaging in the intervention; and 5) to remember that the best way to experience the intervention is by doing one module every 2 weeks.

-

(d)

A final phone call after the post-assessment: to ask them their qualitative opinion about the intervention and remind participants that they will be allowed to use the intervention program any time they want to during the study period, and that we will contact them to do the follow-up assessment.

ICT support will consist of multiple-choice questions about the module’s contents in order to provide the participant with the correct feedback for their responses and a detailed explanation. Furthermore, the participants will receive an automated email encouraging them to continue with the modules if they have not accessed the program for a week. In addition to this automated support, the program offers continued feedback to users through the transversal tools described earlier.

Instruments

Diagnostic interview

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version 5.0.0 (MINI) [61]. It is a structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders. It was designed to be used by clinicians or even by nonclinical personnel after brief training, and it has an administration time of approximately 15 min. The MINI has excellent interrater reliability (K = .88–1.00), and it has been translated and validated in Spanish [62].

Primary outcomes

Depression

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) the BDI-II is a 21-item self-report multiple-choice inventory that is widely used to detect and assess the severity of depressive symptoms. The items, scored on a scale from 0 to 3, cover the different symptoms characterizing major depression disorder in the DSM-IV [57], such as sadness, pessimism, past failure, loss of pleasure, guilty feelings, punishment feelings, suicidal thoughts or wishes, etc. The scores on the scale range from 0 to 63. The internal consistency of the BDI-II is high (alpha = 0.76 to 0.95), and for the Spanish version of the instrument (alpha = 0.87), for both general and clinical populations (alpha = 0.89) [63].

Positive and negative emotionality

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) the PANAS [64] consists of two 10-item mood scales that assess two independent dominant dimensions of affective structure: positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). Each scale ranges from 10 to 50. The PANAS is brief, reliable, and has shown excellent internal consistency (alpha between 0.84 and 0.90) and convergent and divergent validity. The Spanish version has also shown high internal consistency (α = 0.87 and 0.89 for PA and NA in men, respectively, and α = 0.89 and 0.91 for PA and NA in women, respectively [64].

Secondary outcomes and post-module measures

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) the CD-RISC [65] is a brief scale that consists of 25 items. The person must indicate to what extent each statement has been true for him/her in the past month on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 =“has not been true at all” and 4=“true almost always”. The total scores range from 0 to 100; higher scores indicate greater resilience. Previous studies have shown that the CD-RISC has good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha above 0.70) [65].

Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale (ODSIS)

The ODSIS [66] is a brief, 5-item self-report measure for assessing the frequency and severity of depression, as well as functional impairments in pleasurable activities, work or school interference, and social relationship interference associated with depression. The items are scored on a scale from 0 to 4, and they function similarly across clinical and nonclinical samples. The ODSIS has shown excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha between .91 and .94) and good convergent/discriminant validity [66].

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The PSS [67] is a self-report instrument that assesses the level of stress perceived in the past month. It consists of 14 items scored on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The total score range varies between 0 (minimum perceived stress) and 56 (maximum perceived stress). In the present study, a 4-item PSS (PSS-4) was used. This PSS-4 was introduced as a brief version for situations requiring a very short scale or telephone interviews [68]. It has been validated in different studies, showing an internal consistency reliability of 0.76–0.82 [69].

Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS)

The OASIS [70] is a 5-item self-report measure, rated from 0 to 4, that can be used to assess the frequency and severity of anxiety disorders, multiple anxiety disorders, and subthreshold anxiety symptoms. The scale also provides measures of functional impairments in pleasurable activities, work or school interference, and social relationship interference associated with anxiety symptoms. The OASIS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties with good internal consistency (alpha = 0.80), test-retest reliability (K = 0.82), and convergent validity [70,71,72].

Quality of life Inventory (QLI)

The QLI [73] is a brief self-report questionnaire used to measure the perceived quality of life in different areas. The inventory consists of 10 items scored on a scale ranging from 1 to 10. It is calculated by averaging the 10 items, and the maximum score is 10. The QLI assesses aspects related to physical well-being, psychological well-being, self-care and independent functioning, occupational functioning, interpersonal functioning, social emotional support, community and services support, personal fulfillment, spiritual fulfillment, and overall quality of life. The QLI has shown excellent internal consistency (between 0.90 and 0.92), test-retest reliability (0.87), and discriminant validity. The Spanish validation of the QLI [74] has also demonstrated good test-retest reliability (0.89) and discriminant validity.

Pemberton Happiness Index (PHI)

The PHI [75] is a brief instrument to measure different domains of well-being (i.e., general, hedonic, eudemonic, and social). It contains 11 items rated on a scale where 0 = strongly disagree and 10 = strongly agree. The reliability of this scale is quite satisfactory (alpha = 0.89) [75].

Enjoyment Orientation Scale (EOS)

The EOS [76] is a 6-item self-report measure that assesses the extent to which participants try to be receptive and make an effort to be engaged in pleasant things (anticipatory pleasure). This scale is very related to the behavioral activation system that is believed to regulate appetitive motives. The items on the EOS are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”) [76].

Environmental Reward Observation Scale (EROS)

The EROS [77] is a brief, reliable, and valid measure of environmental reward. It consists of a 10-item Likert measure rated from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”), with the total score representing the sum of the 10 items. The Spanish EROS is internally consistent (alpha = 0.86) and valid [77].

Acceptance, satisfaction and usability outcomes

Expectation of treatment scale and opinion of treatment scale these two scales are adapted from Borkovec and Nau [78]. Each scale contains 5 items, regarding whether the treatment is logical, treatment satisfaction, the treatment’s utility for other psychological problems, and the treatment’s usefulness for the patient’s specific problem. The expectation scale is administered at the post-module 2 assessment, when the treatment has been explained to the participants, and the opinion scale is administered at the end of the treatment, with the aim of assessing satisfaction. Our group has used this questionnaire in several research studies [51, 79].

System Usability Scale (SUS)

The SUS [80] is a brief, reliable scale for measuring the usability of a program. It consists of a 10-item questionnaire with 5 response options, from 0 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”). Its purpose is to collect the user’s opinion about the usability of the system, and unacceptable usability may indicate that the user has had technical difficulties with the program. The SUS adjective rating scale (from “Worst imaginable” to “Best imaginable”) will be used to provide a qualitative comparison of usability scores [81].

The study measures and area and time of assessment are summarized in Table 4.

Sample size and power calculations

The a priori sample size determination was performed based on the main objective of this investigation. Following Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, we assumed a proportion of explained variance of low magnitude for the interaction between the type of intervention and the measurement occasion, that is, 0.01. For a significance level of 5%, statistical power of 80%, assumed sphericity, and correlation of .7 between repeated measures (following Rosenthal’s 1991 recommendation), the total sample size needed was 147 participants (49 per intervention group). To this figure, an additional 30% was added to anticipate potential dropouts. Therefore, the total sample size of the study was 192 participants (64 per intervention group). Sample size calculations were carried out with the statistical program G*Power 3.1.9.2 [82].

Statistical analysis

Per protocol and Intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses will be performed, following the CONSORT and CONSORT-eHealth recommendations [56, 83]. Between-group differences in baseline clinical and socio-demographic characteristics will be explored using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous data, and chi-square tests (χ2) for categorical variables. Both normality and multinormality assumptions will be assessed by applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test, skewness and kurtosis indexes, and histogram and Q-Q plots. Levene’s test will be conducted to check homoscedasticity assumptions for equality of variances, and Mauchly’s test to explore sphericity assumptions. Missing data patterns will be assessed, and whether missing data are missing completely at random (MCAR) will be checked with Little’s MCAR test [84]. The ITT principle will be applied for primary and secondary outcomes collected at post-treatment, and at the 3, 6, and 12-month follow-ups. In this regard, the maximum likelihood (ML) method using the Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm will be used to deal with missing data, due to its flexibility in repeated-measures ANOVAs in handling missing data appropriately (i.e., [85, 86]. Nevertheless, several approaches will also be considered and assessed using sensitivity analyses in order to apply the most robust and adequate method based on both missing data patterns and literature recommendations (i.e., [87, 88]. Repeated analysis of variance (rm-ANOVA) will be performed to explore the main and interaction effects of the treatments on all the primary and secondary outcomes. Significant effects will be followed up by pairwise comparisons, such as the Tukey procedure when the homoscedasticity assumption is met, and the Games-Howell procedure if this assumption is not met. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% IC) will be calculated and reported for within- and between-group comparisons, according to authors’ recommendations [89,90,91]. In addition to ITT analyses, per protocol analyses will also be conducted. It is true that these analyses suffer from selection bias, but they will allow us to reach conclusions about the efficacy of the treatment in patients who complete all the intervention modules [92].

For acceptability and usability measures, data analysis will be based on completers. Separate multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for expectations, satisfaction, and usability will be performed, where all items are entered into the MANOVA as dependent variables, and the experimental group as a fixed factor (independent variable).

Finally, multiple regression analysis and mediation analysis will be conducted to explore potential predictors and mediators of depressive symptoms. Mediation analyses will be performed through bootstrap regression analysis using the Preacher and Hayes (2004) approach. All statistical analyses will be conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.

We will review the state of the art analytical methodology for RCT before performing the analyses of the data, in order to use the best statistical analysis procedure. Thus, there may be some variations in the statistical analysis procedures.

Discussion

This paper describes the protocol for a randomized controlled dismantling study of an Internet-based intervention for patients with mild to moderate depressive symptoms. One of the main aims of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of a complete Internet-based intervention for depressive symptoms (including motivation, cognitive restructuring, BA, PPs, and Relapse prevention), the same Internet-based intervention without the PPs component, and the same Internet-based intervention without the BA component, all of them administered over the Internet to patients with mild to moderate depressive symptoms. These three intervention protocols with different therapeutic components will be tested in order to explore the specific contribution of each therapeutic component involved in the treatment of depression and better understand how and why therapies lead to change [20].

Although a large number of psychological interventions have been shown to be effective in the treatment of depression, the specific influence of each therapeutic component is still unknown [15]. Thus, it is crucial to delimit the influence that the specific therapeutic components of psychological interventions can have.

Furthermore, current psychological treatments for depression focus largely on reducing excesses in negative affect rather than on specifically improving deficits in positive affect and well-being [36, 93]. It is well known that depression often involves low levels of positive affect [22, 93] that increase the severity of the problem [94]. Furthermore, people with high levels of positive affect tend to have better well-being and psychological and physical health [95].

In this regard, it is important to include positive affect as an essential target of the treatment by considering well-being and positive functioning to be core elements of the intervention.

Recent literature shows that PPs techniques might have an impact on the decline in clinical symptomatology [22, 36, 96, 97]. These PPs (Well-being Therapy; Quality of Life therapy; Positive Psychotherapy, and Strengths based Counseling) are based on the hypothesis that it is possible to treat depression not only by focusing on decreasing the negative symptoms, but also by directly and primarily building positive emotions and promoting psychological strengths and a meaningful life [27, 31]. Recent findings suggest that explicitly focusing on positive emotions efficiently improves depressive symptoms and helps to achieve more profound change in positive functioning measures [98,99,100]. However, the specific contribution of these PPs in the treatment of depression has scarcely been studied. In fact, in a recent comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of dismantling studies of psychotherapies for adult depression, no study is included that dismantles an intervention with a PPs-based component, and none with an Internet-based intervention [15].

The dismantling design of the current study will allow us to explore the contribution of each main treatment component. More specifically, it will allow us to know how PPs and emotional regulation strategies centered on positive affect work, resulting in a significant shift to optimize treatments for depression. In addition, with the current study, it will be possible to analyze the mediators of changes in depressive symptoms and the acceptability of each intervention.

Moreover, this study is consistent with one of the most important challenges within the field of the treatment of depression, which is the design of new ways to apply treatments to maximize their therapeutic efficiency. Undoubtedly, the use of technology and the Internet can help to achieve this goal and contribute to the dissemination and accessibility of evidence-based treatments. Furthermore, another advantage of the Internet-based interventions is the possibility of making online assessments. Research results encourage the use of online questionnaires because they offer advantages over traditional data collection strategies [101, 102]. Some of these advantages are that missing data can be handled better, and the assessment is easy and immediate [101] and can take place right after the patients finish a psychological component. This could make it easier to know the specific contribution of each component throughout the intervention process.

In sum, this study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized dismantling intervention study for depression with the aim of exploring the contribution of a PPs component and the BA component in an Internet-based intervention. The three protocols are online interventions, helping to reach many people who need psychological treatments and would not otherwise have access to them. Furthermore, acceptability and usability measures will be included in order to assess the intervention’s feasibility and acceptance, in addition to an efficacy study. Finally, potential mediator mechanisms will be explored to identify the variables that lead to changes in depressive symptoms.

We are aware that this study has limitations. One of them is that the number of BA and PPs modules in the IBAc and IPPc is higher than in the IGc, although the clinical content is the same in the global protocol and in the protocols for the BA and PPs components. The reason for this is that the three protocols contain the same total number of modules (8 modules per each) and a similar number of words. We give all the patients the same amount of time to do the intervention to try to control this. Another limitation is that the dropout rates are expected to be high (around 30%) [103]. Efforts will be made to minimize the dropout rates by providing ICT and human support. Approaches to handling missing data will be considered and assessed using sensitivity analyses in order to apply the most robust and adequate method, based on both the missing data patterns and recommendations found in the literature (i.e., [87, 88]. In addition, difficulties in the recruitment phase will be considered.

In summary, this study extends the current literature about Internet-based interventions for depression. If positive results are achieved, they may have an important impact by providing better knowledge about the core elements of evidence-based treatments for depression.

Abbreviations

- AES:

-

Advanced Encryption Standard

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variance

- BA:

-

Behavioral Activation

- BDI-II:

-

Beck Depression Inventory-II

- BL:

-

Baseline

- CBT:

-

Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- EM:

-

Expectation Maximization

- EOS:

-

Enjoyment Orientation Scale

- EROS:

-

Environmental Reward Observation Scale

- FU:

-

Follow-Ups

- IBAc:

-

Internet-based Behavioral Activation protocol condition

- IGc:

-

Internet-based Global Protocol condition

- IPPc:

-

Internet-based Positive Psychotherapy protocol condition

- ITT:

-

Intention-to-treat

- MANOVA:

-

Multivariate Analysis of Variance

- MCAR:

-

Missing Completely at Random

- MINI 5.0.0:

-

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version (5.0.0)

- ML:

-

Maximum Likelihood

- OASIS:

-

Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale

- ODSIS:

-

Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale

- PANAS:

-

Positive and Negative Affect Scale

- PHI:

-

Pemberton Happiness Index

- Post-T:

-

Post-Treatment

- PPs:

-

Positive Psychotherapeutic strategies

- PSS:

-

Perceived Stress Scale

- QLI:

-

Quality of Life Index

- RS-14:

-

Resilience Scale-14

- SPIRIT:

-

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials

- SUS:

-

System Usability Scale

References

Haro JM, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Bitter I, Demotes-Mainard J, Leboyer M, Lewis SW, et al. ROAMER: roadmap for mental health research in Europe. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(S1):1–14.

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. Samet J, editor. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442 1. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442.

Cuijpers P, Andersson G, Donker T, van Straten A. Psychological treatment of depression: results of a series of meta-analyses. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(6):354–64. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2011.596570.

Cuijpers P, Gentili C. Psychological treatments are as effective as pharmacotherapies in the treatment of adult depression: a summary from Randomized Clinical Trials and neuroscience evidence. Res Psychother Psychopathol Process Outcome. 2017;20(2). https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2017.273.

Churchill R, Hunot V, Corney R, Knapp M, McGuire H, Tylee A, et al. A systematic review of controlled trials of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of brief psychological treatments for depression. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 2001;5(35):1–173.

Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, Dobson KS. A meta-analysis of cognitive-Behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can J Psychiatr. 2013;58(7):376–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371305800702.

Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(3):318–26.

Ekers D, Richards D, Gilbody S. A meta-analysis of randomized trials of behavioural treatment of depression. Psychol Med. 2008;38(05):611–23.

Cuijpers P, Donker T, Weissman MM, Ravitz P, Cristea IA. Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(7):680–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15091141.

Malouff J, Thorsteinsson E, Schutte N. The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(1):46–57.

Antony MM, Stein MB. Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders. Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 701.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (Great Britain), Royal College of Psychiatrists. Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults. United Kingdom: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2010.

Nathan PE, Gorman JM. A Guide to Treatments That Work. Oxford: University Press; 2015.

Butler A, Chapman E, Forman E, Beck A. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(1):17–31.

Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M, Hollon SD. Component studies of psychological treatments of adult depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother Res. 2019;0(0):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1395922.

Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, Schmaling KB, Kohlenberg RJ, Addis ME, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(4):658–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658.

Hopko DR, Lejuez CW, Lepage JP, Hopko SD, McNeil DW. A brief behavioral activation treatment for depression. Behav Modif. 2003;27(4):458–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445503255489.

MacPherson L, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AK, Rodman S, Strong DR, Kahler CW, et al. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(1):55–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017939.

Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432.

Kazdin AE. Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychother Res 2009;19(4–5):418–428. Available from: doi. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802448899

Institute of Medicine. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2015.

Ruini C. Positive psychology in the clinical domains. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

Fava GA, Ruini C. Development and characteristics of a well-being enhancing psychotherapeutic strategy: well-being therapy. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2003;34(1):45–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(03)00019-3.

Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Salmaso L, Mangelli L, et al. Well-being therapy of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(1):26–30.

Ruini C, Albieri E, Vescovelli F. Well-being therapy: state of the art and clinical exemplifications. J Contemp Psychother. 2015;45(2):129–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-014-9290-z.

Ruini C, Fava GA. Well-being therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):510–9.

Ryff CD. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in the science and practice of Eudaimonia. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(1):10–28.

Frisch MB. Quality of life therapy: applying a life satisfaction approach to positive psychology and cognitive therapy. Wiley: Hoboken; 2006. p. 353.

Frisch MB. Evidence-based well-being/positive psychology assessment and intervention with quality of life therapy and coaching and the quality of life inventory (QOLI). Soc Indic Res. 2013;114(2):193–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0140-7.

Rashid T. Positive psychotherapy: a strength-based approach. J Posit Psychol. 2015;10(1):25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.920411.

Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774.

Peterson C, Seligman MEP. Character strengths and virtues : a handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. p. 800.

Proyer RT, Gander F, Wellenzohn S, Ruch W. Strengths-based positive psychology interventions: a randomized placebo-controlled online trial on long-term effects for a signature strengths- vs. a lesser strengths-intervention. Front Psychol. 2015;22:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00456/abstract.

Rashid T. Positive interventions in clinical practice. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):461–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20588.

Sin NL, Della Porta MD, Lyubomirsky S. Tailoring positive psychology interventions to treat depressed individuals. In: Donaldson SI, Csikszentmihalyi M, Nakamura J, editors. Series in applied psychology Applied positive psychology: Improving everyday life, health, schools, work, and society. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. p. 79–96.

Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):119.

Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):467–87.

Watson D, Naragon-Gainey K. On the specificity of positive emotional dysfunction in psychopathology: evidence from the mood and anxiety disorders and schizophrenia/schizotypy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(7):839–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.002.

Pressman SD, Jenkins BN, Moskowitz JT. Positive Affect and Health: What Do We Know and Where Next Should We Go? Annu Rev Psychol. 2018;70(1):627–50.

Werner-Seidler A, Banks R, Dunn BD, Moulds ML. An investigation of the relationship between positive affect regulation and depression. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(1):46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.11.001.

Kazdin AE, Blase SL. Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6(1):21–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393527.

Kazdin AE. Technology-based interventions and reducing the burdens of mental illness: perspectives and comments on the special series. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22(3):359–66.

Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(4):196–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070903318960.

Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, Titov N. Computer Therapy for the Anxiety and Depressive Disorders Is Effective, Acceptable and Practical Health Care: A Meta-Analysis. Baune BT, editor. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13196.

Johansson R, Andersson G. Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(7):861–70.

Karyotaki E, Riper H, Twisk J, Hoogendoorn A, Kleiboer A, Mira A, et al. Efficacy of self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressive symptoms a meta-analysis of individual participant data. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):351–9.

Karyotaki E, Kemmeren L, Riper H, Twisk J, Hoogendoorn A, Kleiboer A, et al. Is self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) harmful? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48:1–11.

Borkovec TD, Castonguay LG. What is the scientific meaning of empirically supported therapy? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(1):136–42.

Bell EC, Marcus DK, Goodlad JK. Are the parts as good as the whole? A meta-analysis of component treatment studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(4):722–36.

Vazquez FL, Torres A, Di-az O, Otero P, Blanco V, Hermida E. Protocol for a randomized controlled dismantling study of a brief telephonic psychological intervention applied to nonprofessional caregivers with symptoms of depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0682-8.

Botella C, Mira A, Moragrega I, García-Palacios A, Bretón-López J, Castilla D, et al. An internet-based program for depression using activity and physiological sensors: efficacy, expectations, satisfaction, and ease of use. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:393.

Mira A, Bretón-López J, García-Palacios A, Quero S, Baños RM, Botella C. An internet-based program for depressive symptoms using human and automated support: a randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:987–1006.

Montero-Marín J, Araya R, Pérez-Yus MC, Mayoral F, Gili M, Botella C, et al. An Internet-Based Intervention for Depression in Primary Care in Spain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(8):e231 [cited 2018 Oct 20].

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2001;1(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-1-2.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869.

Eysenbach G. CONSORT-EHEALTH Group. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e126.

Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586.

Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche PC, Krleža-Jerić K. SPIRIT 2013 statement : defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):200–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Chambless DL. In defense of dissemination of empirically supported psychological interventions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1996;3(3):230–5.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;(59 Suppl 2):22–33 quiz 34–57.

Ferrando L, Bobes J, Gibert J. MINI. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Versión en Español 5.0.0 DSM-IV. Instrumentos detección y orientación diagnóstica, vol. 0; 2000. p. 2–26.

Sanz Fernández J, Navarro ME, Vázquez VC. Adaptación española del inventario para la depresión de Beck-II: 1. Propiedades psicométricas en estudiantes universitarios. Análisis y Modif Conduct. 2003;29(124):239–88.

Sandín B, Chorot P, Lostao L, Joiner TE, Santed ME, Valiente R. Escalas PANAS de afecto positivo y negativo: validación factorial y convergencia transcultural. Psicothema. 1999;11(1):37–51.

Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82.

Bentley KH, Gallagher MW, Carl JR, Barlow DH. Development and validation of the overall depression severity and impairment scale. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(3):815–30.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983 Dec;24(4):385.

Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988. p. 31–67.

Lee E-H. Erratum to Review of the Psychometric Evidence of the Perceived Stress Scale [Asian Nursing Research 6 (2012) 121–127]. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2013;7(3):160.

Campbell-Sills L, Norman SB, Craske MG, Sullivan G, Lang AJ, Chavira DA, et al. Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: the overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). J Affect Disord. 2009;112(1–3):92–101.

Norman SB, Hami Cissell S, Means-Christensen AJ, Stein MB. Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(4):245–9.

Norman SB, Campbell-Sills L, Hitchcock CA, Sullivan S, Rochlin A, Wilkins KC, et al. Psychometrics of a brief measure of anxiety to detect severity and impairment: the overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(2):262–8.

Mezzich JE, Cohen NL, Ruiperez MA, Banzato CEM, Zapata-Vega MI. The multicultural quality of life index: presentation and validation. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):357–64.

Mezzich JE, Ruipérez MA, Pérez C, Yoon G, Liu J, Mahmud S. The Spanish version of the quality of life index: presentation and validation. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(5):301–5.

Hervás G, Vázquez C. Construction and validation of a measure of integrative well-being in seven languages: the Pemberton happiness index. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-66.

Hervás G, Vázquez C. Enjoying every little thing: orientation to daily gratifications as a mediator between extraversion and well-being. Braga: Comunicación presentada en la III European Conference on Positive Psychology; 2006.

Armento MEA, Hopko DR. The environmental reward observation scale (EROS): development, validity, and reliability. Behav Ther. 2007;38(2):107–19.

Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3(4):257–60.

Botella C, Gallego MJ, Garcia-Palacios A, Baños RM, Quero S, Alcañiz M. The acceptability of an internet-based self-help treatment for fear of public speaking. Br J Guid Couns. 2009;37(3):297–311.

Brooke J. SUS - a quick and dirty usability scale. In: Usability Evaluation in Industry. London: Taylor and Francis; 1996.

Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2008;24(6):574–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447310802205776.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332.

Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:1198–202.

Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move Over ANOVA. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(3):310.

Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2002.

Salim A, Mackinnon A, Christensen H, Griffiths K. Comparison of data analysis strategies for intent-to-treat analysis in pre-test–post-test designs with substantial dropout rates. Psychiatry Res. 2008;160(3):335–45.

Thabane L, Mbuagbaw L, Zhang S, Samaan Z, Marcucci M, Ye C, et al. A tutorial on sensitivity analyses in clinical trials: the what, why, when and how. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):92.

Botella J, Sánchez Meca J. Meta-análisis en ciencias de sociales y de la salud. Síntesis; 2015.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Cumming G, Calin-Jageman R. Introduction to the new statistics : estimation, open science, and beyond; 2017. p. 560.

Wright CC, Sim J. Intention-to-treat approach to data from randomized controlled trials: a sensitivity analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(9):833–42.

Craske MG, Meuret AE, Ritz T, Treanor M, Dour HJ. Treatment for anhedonia: a neuroscience driven approach. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(10):927–38.

Gilbert KE, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Gruber J. Positive emotion dysregulation across mood disorders: how amplifying versus dampening predicts emotional reactivity and illness course. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(11):736–41.

Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218–26.

Chaves C, Lopez-Gomez I, Hervas G, Vazquez C. A comparative study on the efficacy of a positive psychology intervention and a cognitive behavioral therapy for clinical depression. Cognit Ther Res. 2017;41(3):417–33.

Lopez-Gomez I, Chaves C, Hervas G, Vazquez C. Comparing the acceptability of a positive psychology intervention versus a cognitive behavioural therapy for clinical depression. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017;24(5):1029–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2129.

Geschwind N, Arntz A, Bannink F, Peeters F. Positive cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of depression: a randomized order within-subject comparison with traditional cognitive behavior therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.03.005.

Mira A, Bretón-López J, Enrique A, Castilla D, Garcia-Palacios A, Baños R, Botella C. Exploring the incorporation of a positive psychology component in a cognitive behavioral internet-based program for depressive symptoms. Results throughout the intervention process. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2360.

Proyer RT, Wellenzohn S, Gander F, Ruch W. Toward a better understanding of what makes positive psychology interventions work: predicting happiness and depression from the person × intervention fit in a follow-up after 3.5 years. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being. 2015;7:108–28.

Carlbring P, Brunt S, Bohman S, Austin D, Richards J, Öst L-G, et al. Internet vs. paper and pencil administration of questionnaires commonly used in panic/agoraphobia research. Comput Human Behav. 2007;23(3):1421–34.

Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Rück C, Furmark T, Carlbring P, Lindefors N, et al. Internet administration of self-report measures commonly used in research on social anxiety disorder: a psychometric evaluation. Comput Human Behav. 2010;26(4):736–40.

Kaltenthaler E, Parry G, Beverley C, Ferriter M. Computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(03):181–4.

Acknowledgements

Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Spain) (Plan Nacional PSI2014-60980-JIN); the Institute of Health Carlos III (ISCiii) CIBERobn is an initiative of ISCIII; Government of Aragón; Departament of Innovation, Research; University and FEDER “Construyendo desde Aragón” and Asociación Española de Ayuda Mutua contra Fobia Social y Trastornos de Ansiedad (AMTAES).

Funding

Funding for the study was provided by: Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Spain) (Plan Nacional PSI2014–60980-JIN) and CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición-ISCIII CB06/03/0052. The study protocol was peer-reviewed by the funding bodies. The funding institutions had no role in the design of the study and will not have any role during its execution, analyses and interpretation of the data, or the decision to submit the results.

Availability of data and materials

It is not possible to share the data because the study is in progress. We are now at the stage of data recruitment. Only principal investigators will have access to the final trial dataset, and it will be considered for publication. Trial results will be communicated to participants, healthcare professionals, the public, and other relevant groups (i.e., via professional websites, non-professional social-networks, and announcements in newspapers). The research team will make the findings publicly available at national and international conferences, and in peer-reviewed journal publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM drafted the manuscript with important contributions from AD-G, JB-L and CB; AM, in collaboration with AD-G, JB-L, AG-P and CB designed the study and participated in each of its phases. SR collaborated in the manuscript development and participated in each study phase. AM, DCa, DCb and AG-P carried out the Internet-based adaptation of the treatment protocol with important contributions of RB, CB and JB-L. All authors participated in the review and revision of the manuscript and have approved the final manuscript to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Author’s information

AM (PhD) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology and Sociology, at the University of Zaragoza. AM is also a member of the Investigación en comportamiento, salud y tecnologías (ICST) group at the University of Zaragoza and a member of LabPsiTec (Laboratory of Psychology and Technology) (www.labpsitec.com) at Universitat Jaume I. AD-G is a PhD postdoctoral researcher at Universitat Jaume I in the Department of Basic and Clinical Psychology, and Psychobiology, and was awarded a grant by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (FPI-MINECO) (BES-2015-072360). AD-G is also a member of LabPsiTec. DCa is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology and Sociology, at the University of Zaragoza. DCa is also a member of LabPsiTec. DCb is a postdoctoral researcher at Universitat Jaume I in the Department of Basic and Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology, and currently holds a grant from the Generalitat Valenciana (VALi+d) (APOSTD/2018/055). DCb is also a member of Labpsitec. SR is a PhD student in Clinical Psychology at Universitat Jaume I in the Department of Basic and Clinical Psychology, and Psychobiology. JB-L, AG-P and CB are Full Professors of Clinical Psychology at Universitat Jaume I in the Department of Basic and Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology, and they are also members of Labpsitec. RB is a full professor at the Universitat de València, in the Department of Personality, Evaluation and Psychological Treatments, and she is a member of Labpsitec.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies, and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript. The study follows the guidelines of the Declaration Helsinki and existing guidelines in Spain and the European Union for the protection of patients in clinical trials. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitat Jaume I (Castellón, Spain; approval number 4/2017; 4 July 2017). All participants interested in participating signed a written informed consent form. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrial.gov as NCT03159715.

Consent for publication

“Not applicable” in this section.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mira, A., Díaz-García, A., Castilla, D. et al. Protocol for a randomized controlled dismantling study of an internet-based intervention for depressive symptoms: exploring the contribution of behavioral activation and positive psychotherapy strategies. BMC Psychiatry 19, 133 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2099-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2099-2