Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to examine the characteristics of diurnal cortisol rhythm in childhood obesity and its relationships with anthropometry, pubertal stage and physical activity.

Methods

Thirty-five children with obesity (median age: 11.80[interquartile range 10.30, 13.30] and median BMI z-score: 3.21[interquartile range 2.69, 3.71]) and 22 children with normal weight (median age: 10.85[interquartile range 8.98, 12.13] and median BMI z-score: − 0.27[interquartile range − 0.88, 0.35]) were recruited. Saliva samples were collected at 08:00, 16:00 and 23:00 h. Cortisol concentrations at 3 time points, corresponding areas under the curve (AUCs) and diurnal cortisol slope (DCS) were compared between the two groups. Anthropometric measures and pubertal stage were evaluated, and behavioural information was obtained via questionnaires.

Results

Children with obesity displayed significantly lower cortisol08:00 (median [interquartile range]: 5.79[3.42,7.73] vs. 8.44[5.56,9.59] nmol/L, P = 0.030) and higher cortisol23:00 (median [interquartile range]: 1.10[0.48,1.46] vs. 0.40[0.21,0.61] nmol/L, P < 0.001) with a flatter DCS (median [interquartile range]: − 0.29[− 0.49, 0.14] vs. -0.52[− 0.63, 0.34] nmol/L/h, P = 0.006) than their normal weight counterparts. The AUC increased with pubertal development (AUC08:00–16:00:P = 0.008; AUC08:00–23:00: P = 0.005). Furthermore, cortisol08:00 was inversely associated with BMI z-score (β = − 0.247, P = 0.036) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) (β = − 0.295, P = 0.027). Cortisol23:00 was positively associated with BMI z-score (β = 0.490, P<0.001), WHtR (β = 0.485, P<0.001) and fat mass percentage (FM%) (β = 0.464, P<0.001). Absolute values of DCS were inversely associated with BMI z-score (β = − 0.350, P = 0.009), WHtR (β = − 0.384, P = 0.004) and FM% (β = − 0.322, P = 0.019). In multivariate analyses adjusted for pubertal stage and BMI z-score, Cortisol08:00, AUC08:00–16:00 and absolute values of DCS were inversely associated with the relative time spent in moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity (P < 0.05). AUC16:00–23:00 was positively associated with relative non-screen sedentary time and negatively associated with sleep (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

The disorder of diurnal salivary cortisol rhythm is associated with childhood obesity, which is also influenced by puberty development and physical activity. Thus, stabilizing circadian cortisol rhythms may be an important approach for childhood obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Accompanied by economic development and lifestyle changes, the prevalence of childhood obesity has increased rapidly worldwide, leading to obesity-related metabolic diseases in adulthood, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [1, 2]. Indeed, the unhealthy lifestyle and academic demands of children are increasingly interfering with biological rhythms, which might contribute to childhood obesity and negative health outcomes [3, 4]. Therefore, it is essential to identify novel contributors to the underlying physiology of childhood obesity.

Cortisol is a primary product of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and acts as the terminal effector of this axis on other systems [5]. In both human and animal models, cortisol has been causally demonstrated to promote fat accumulation and weight gain as well as glucose homeostasis and lipid metabolism [6, 7]. Considering that the production, secretion and abundance of cortisol are regulated in a robust time-of-day-dependent manner [8], the diurnal cortisol rhythm is a good indicator for comprehensive evaluation of HPA axis activity. Cortisol rhythms are believed to be established between 2 and 9 months in early life [9], as mediated by a combination of influences such as the light-dark cycle, pubertal development, feeding, sleep, and physical activity [10]. Under non-stress conditions, the secretion and release of cortisol follows a typical circadian rhythm: cortisol rapidly increases 30 to 40 min after awakening, followed by a sharp decline during the next few hours and a gradually decline during the remainder of the day until reaching the lowest level at midnight [11, 12].

An interaction between the HPA axis and obesity has long been proposed. On the one hand, cortisol controls body weight via effects on both food intake and energy expenditure as well as adipogenic pathways in abdominal adipose tissue [13]. On the other hand, obesity constitutes a chronic stressor and in turn alters the activity of the stress axis [14]. Recently, it has been proposed that obesity is associated with circadian disruption and often accompanied by altered HPA axis rhythmicity [5]. Adults with obesity usually display blunted diurnal HPA axis functioning, which manifests as decreased cortisol variability, lower morning levels, or a smaller change in cortisol throughout the day [15,16,17]. However, studies of diurnal cortisol patterns in childhood obesity have resulted in different findings. For example, Kjolhede reported that average salivary cortisol levels throughout the day were significantly lower in children with obesity [18], whereas Hillman showed that with an increasing degree of adiposity in adolescent girls, there may be reduced serum cortisol levels during the day and increased levels at night [14]. Conversely, another study reported no significant association between the HPA axis and percent body fat in pre-pubertal children with obesity [19]. A potential explanation for these variable findings is with regard to methodological differences such as different measurement methods (e.g., enzyme immunoassay, radioimmunoassay, chemiluminescence immunoassay) and sampling time. Considering the characteristics of children’s growth, regulation of the HPA axis in children may be affected by more complex factors than those in adults, such as age, pubertal development and stress-related activities (dietary consumption, physical activities, etc.). Therefore, exploring the factors influencing children’s HPA axis may help in reaching a complete understanding of the links between dysregulation of the HPA axis and childhood obesity.

In the present study, we explored the characteristics of diurnal cortisol rhythm in children and adolescents with obesity by repeated sampling of salivary cortisol over the course of a day. Moreover, we examined relationships of cortisol activity with the degree of adiposity, pubertal stage and physical activity. This information may contribute to our understanding of the associations between chronodisruption, obesity and lifestyle to provide new insight for the primary prevention of childhood obesity.

Methods

Participants

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 57 children and adolescents aged 6–15 years were recruited from the Department of Endocrinology and Child Health Care of Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University from July 2018 to June 2019. According to WHO standards [20], the subjects were divided into a normal weight group (− 2 < BMI z-score < 1) and an obesity group (BMI z-score > 2). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a history of chronic diseases (except obesity), such as epilepsy, diabetes, hypothyroidism, tumours, mental illness, precocious puberty or short stature; (2) use of exogenous steroids in the past 3 months; (3) a history of surgery, trauma or other stress events in the past 3 months; (4) use of a medication known to affect hormones; or (5) female menstrual period.

The study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University Ethical Committee. Prior to inclusion in the study, the parents provided written informed consent.

Measures

Anthropometric measures

All subjects fasted for 12 h overnight and emptied urine and stool prior to measurements. Body composition was determined using the bioelectrical impedance method (Inbody J20, Biospace, Korea), including body fat mass, fat mass percentage (FM%) and skeletal muscle mass. According to a standard protocol, height and weight were measured by experienced researchers with precisions of 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively. BMI was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of height (in metres). Because children’s BMI varies with age and sex, BMI was converted to BMI z-score according to the World Health Organization’s Child Growth Standards (2006). Waist circumference (WC) was measured in centimetres to the nearest 0.1 cm. The waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) was calculated as WC (in centimetres) divided by height (in centimetres).

Pubertal stage

Professional paediatricians performed visual inspection and palpation to determine pubertal stage. Females were matched for breasts and pubic hair and males for genitalia and pubic hair [21]. The stage of pubertal development (I-V period) was assessed according to Tanner staging criteria, with Tanner II as the hallmark of puberty initiation. For analysis of different degrees of pubertal development, the Tanner stage was categorized into three levels: pre-pubertal (Tanner I), early pubertal (Tanner II and III) and late pubertal (Tanner IV and V) [21].

Salivary cortisol analysis

Salivary cortisol reflects the levels of biologically active, non-protein-bound cortisol in serum and follows the circadian variation in serum cortisol [22]. Salivary cortisol correlates strongly with plasma cortisol [23] and is less prone to variability due to changes in cortisol-binding proteins [24]. Due to its easy, non-invasive collection and convenient transportation and storage, salivary cortisol is widely used for paediatric research.

Salivary samples were collected at 8:00, 16:00 and 23:00 h in a quiet state after a fast of 4 h. A commercial Salivette® (SARSTEDT AG &Co, Germany) tube containing a cotton wool swab was used to collect saliva. The swab was rotated in the mouth for at least 5 min and inserted back into the tube. The cortisol samples, which are stable at room temperature for a number of days,[23] were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min within 24 h to obtain clear saliva with low viscosity, and 500 μL of saliva was pipetted into the EP tube with a micropipette. The saliva samples were stored at − 80 °C after being dispensed.

Using an Elecsys reagent kit and a Cobas e immunoassay analyser (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany), cortisol levels were determined by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) with a high sensitivity of 0.054 ng/ml and intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation below 10%. Areas under the curve relative to ground (AUCs) represent the total amount of cortisol exposure during the portions of the diurnal cortisol cycle by the trapezoidal method [25]. The diurnal cortisol slope (DCS) is characterized as the decline in cortisol over the day and is calculated by the formula rise over run as the slope of the line from the first time point value to the last measured point [26]. It has been proven that there is no difference between linear regression and rise over run formulas [26]. Thus, we calculated HPA axis rhythm measures based on cortisol levels at 3 time points, AUC08:00–16:00, AUC16:00–23:00 and AUC08:00–23:00, as well as DCS.

Assessment of glucose and lipid metabolism

Blood samples were taken at 8:00 after an overnight fast of 12 h to test fasting glucose (FG), fasting insulin (FI), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG) in the obesity group and part of the normal weight group. Insulin resistance was determined by the formula of the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) = ([fasting insulin (lU/mL) × fasting glucose (mmol/L)]/ 22.5.

Questionnaires for physical activities

Children’s sleep parameters were collected by parental questionnaire. Parents reported children’s bedtime and wake-up time on weekdays and weekends during the previous month. The average sleep duration was calculated by the following formula: (sleep duration on weekdays× 5 + sleep duration on weekends× 2)/7 [27].

The Chinese Version of the Children’s Leisure Activities Study Survey questionnaire was used to assess the physical activity of the children. The questionnaire was completed by the children with the assistance of their parents, and the reliability and validity of the Chinese version has been verified [28]. A checklist of 31 physical activities and 13 sedentary behaviours was included in the questionnaire. According to the intensity of physical activity, there were 15 activities classified as vigorous-intensity physical activities (VPA, > 6 METs) and 16 activities classified as moderate-intensity (MPA, 3–5.9 METs) [28]. For data analysis, screen time consisted of 3 sedentary behaviours (SB, including watching TV or movie, playing computer games, surfing the internet or playing on the phone); the other 10 were considered non-screen sedentary behaviours.

Statistical analyses

IBM SPSS Statistics software (Version 24.0) was used, and the level of significance was accepted with P < 0.05. The results are expressed as the means ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. The normality of data was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Cortisol variables with a skewed distribution were logarithmically transformed for correlational analysis. Significant differences between the normal weight and obesity groups were analysed using t-tests or Mann–Whitney U-tests. Chi-square tests were applied to compare categorical variables between two groups. Differences in HPA axis measures among puberty groups were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Multiple linear regressions were performed to assess the correlation of cortisol levels with different anthropometric variables and physical activities. Spearman’s correlations were employed to assess the correlation of cortisol variables with testosterone, glucose or lipid metabolism in obese children .

For analysis of 24-h movement, compositional data analysis was used following the guide of Chastin and colleagues [29]. Four compositional linear regression models were conducted for each health indicator with each behaviour sequentially entered into the model via log–ratio transformation [30]. Models examined the combined effect of the relative distribution of all movement behaviours with each health indicator [29]. Model P values and R2 coefficients were the same across all 4 linear regression models. Next, models assessed the association between the time spent in each movement behaviour relative to the time spent in the other movement behaviours and each health indicator. The first coefficient and its P value for each rotated model were used to determine whether the individual movement behaviour was significantly positively or negatively associated with each health indicator relative to the time spent in the other movement behaviours [31]. In summary, the compositional analysis is a multiple linear regression model where the cortisol measures were modelled as a function of sleep, screen time, non-screen time, and MVPA.

Results

Baseline characteristics

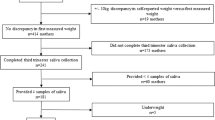

A total of 57 participants were enrolled in the study and divided into a normal weight group (n = 22) and an obesity group (n = 35) according to BMI. Demographic, anthropometric and behavioural characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were no differences between the obesity group and the normal weight group in terms of age, sex, pubertal stage, height, sleep duration or MVPA minutes.

Diurnal cortisol patterns

Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for HPA axis rhythmicity in all subjects, which showed peak cortisol levels in the morning and a nadir at midnight. Moreover, the children with obesity displayed lower cortisol levels at 08:00 (P = 0.030) and AUC08:00–16:00 (P = 0.027) and higher levels at 23:00 (P < 0.001) than their normal weight counterparts. Figure 1 depicts the variation in the diurnal cortisol curve from 08:00 to 23:00 based on BMI category, with notably flatter trajectories of circadian cortisol observed in the children with obesity.

Measures of the HPA axis and pubertal stage

There were no significant correlations between HPA axis measures and sex or age. We then tested the hypothesis that cortisol AUC may be influenced by puberty, which was proposed in other studies [32, 33]. The AUC increased with pubertal development (AUC08:00–16:00:P = 0.008; AUC08:00–23:00: P = 0.005; ANOVA). After adjustments for BMI, the above relationships remained (AUC08:00–16:00: P = 0.002; AUC08:00–23:00: P = 0.002; ANCOVA), as shown in Fig. 2. Moreover, testosterone was positively related to AUC08:00–16:00 (r = 0.407, P = 0.023) and AUC08:00–23:00 (r = 0.443, P = 0.014) in children with obesity.

Comparison of HPA axis measures among different puberty groups. Cortisol variables were logarithmically transformed. Box plots represent interquartile range with the symbol +, inside the box plot representing the mean score. a: P<0.05 Pre-pubertal vs Late pubertal; b: P<0.05 Early pubertal vs Late pubertal

Measures of the HPA axis and anthropometry

The results of multiple regression for associations between HPA axis measures and anthropometry in all participants are shown in Table 3. Cortisol08:00 was inversely associated with BMI z-score (β = − 0.247, P = 0.036) and WHtR (β = − 0.295, P = 0.027). Cortisol23:00 was positively associated with BMI z-score (β = 0.490, P<0.001), WHtR (β = 0.485, P<0.001) and FM% (β = 0.464, P<0.001), and AUC08:00–16:00 was inversely associated with BMI z-score (β = − 0.288, P = 0.033) and WHtR (β = − 0.316, P = 0.020). Absolute values of DCS were inversely associated with BMI z-score (β = − 0.350, P = 0.009), WHtR (β = − 0.384, P = 0.004) and FM% (β = − 0.322, P = 0.019). After adjustments for puberty, cortisol08:00 was inversely associated with BMI z-score (β = − 0.247, P = 0.048) and WHtR (β = − 0.271, P = 0.030). Cortisol23:00 was positively associated with BMI z-score (β = 0.454, P<0.001), WHtR (β = 0.484, P<0.001) and FM% (β = 0.451, P<0.001), and absolute values of DCS were inversely associated with BMI z-score (β = − 0.327, P = 0.013), WHtR (β = − 0.366, P = 0.005) and FM% (β = − 0.313, P = 0.017).

HPA axis measures and 24-h physical activity

For the entire sample, correlations of each movement behaviour with HPA axis measures relative to the other movement behaviours are displayed in Table 4. After adjustments for pubertal stage and BMI z-score, inverse associations between cortisol08:00 (γMVPA = − 0.107; P = 0.018), AUC08:00–16:00 (γMVPA = − 0.081; P = 0.038), and absolute values of DCS (γMVPA = − 0.150; P = 0.007) with the time spent in MVPA relative to other movement behaviours were detected. Moreover, AUC16:00–23:00 correlated positively with time spent in non-screen sedentary behaviours (γnon-screen SB = 0.169; P = 0.009) and negatively with the relative time spent in sleeping (γsleep = − 0.212; P = 0.018).

Measures of the HPA axis and glucose or lipid metabolism

There were no significant correlations between HPA axis measures and serum glucose or lipid levels, as shown in Table 5.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we report the influences of obesity, puberty and physical activity on diurnal cortisol rhythm in children and adolescents. We found a dampened circadian cortisol rhythm in children with obesity, and flatter and less sharply declining slopes correlated with degrees of adiposity. The altered dynamics of the HPA axis also appeared to be influenced by puberty and the distribution of 24-h movement. Therefore, stabilizing circadian cortisol rhythms through circadian regulation strategies may be an important approach for preventing childhood obesity.

HPA axis dysfunction is a risk factor for metabolic diseases such as obesity and is closely related to negative health outcomes. It has been proven that individuals with obesity may display blunted diurnal HPA axis functioning, which mainly manifests as decreased cortisol variability, lower morning levels, or elevated evening levels [15,16,17]. As previously reported, obese Zucker rats lack a circadian rhythm of 11β-HSD1 gene expression in the hippocampus, which may contribute to dampened diurnal variation of circulating corticosterone levels [34]. One paediatric study demonstrated that daytime cortisol levels are inversely associated but that night-time levels are positively associated with BMI z-score and central adiposity [14]. In adults, higher BMI or WHtR correlates with a flatter diurnal cortisol slope, suggesting a shallower decline throughout the day [25, 35]. These studies incorporated multiple sampling time points, allowing more precise slope measurement and more reliable results for associations between cortisol rhythms and obesity. Similar to the above studies, we show that salivary cortisol levels were lower in the morning and higher at night with flatter and less sharply declining cortisol slopes in children with obesity than in those with a normal weight. Moreover, we found salivary cortisol slopes and night-time cortisol to be positively related to weight gain, abdominal fat distribution (WHtR) and body fat percentage in all participants. Such findings are supported by a large cross-sectional study of adults, which showed that bedtime salivary cortisol output tended to increase with BMI, indicating that individuals with obesity display abnormal HPA hyperactivity at night [36]. However, other paediatric studies have reported different findings. Based on the HPLC-MS/MS method, Chu showed higher morning salivary cortisol and morning urinary cortisol in children with obesity aged 4–5 years [37], and Kjolhede presented an inverse association between obesity and morning or evening salivary cortisol levels in children aged 6–12 years by EIA [18]. Such inconsistent findings might result from single sampling time points or different sampling times, cortisol measurements or age distributions.

Recent human studies have shown that cortisol concentrations increase significantly throughout puberty and adolescence [38, 39], which is consistent with our findings. The increased salivary cortisol AUC might reflect higher overall activity of the adrenal gland throughout puberty. In fact, the developmental process of puberty, along with endocrine changes, has been suggested to influence HPA axis functioning [40]. We also found that testosterone in children with obesity correlated positively with AUC08:00–16:00 and AUC08:00–23:00, consistent with the phenomenon of co-activation, where cortisol and testosterone (and dehydroepiandrosterone) are positively linked within an individual [41]. Accordingly, these findings highlight the important role of gonadal hormones in the development of the circadian cortisol cycle during puberty, indicating that puberty is a highly interrelated variable and should be included as a covariate in studies seeking to explore the relationship between cortisol rhythms and adolescent obesity.

Compositional analyses provide an appropriate statistical means for understanding the collective health implications of finite, co-dependent, 24-h movement behaviours [29]. In our results, the relative time spent in MVPA was related to lower morning cortisol concentrations, daytime cortisol output (AUC08:00–16:00) and flatter DCS, independent of puberty and BMI z-score. Labsy pointed out that acute exercise does not significantly affect steroid circadian rhythms but that medium-to-long term training, intended as chronic exercise, appeared to play a key role as a synchronizer for the whole circadian system [10]. Thus far, chronic physical activity has been reported to lower diurnal HPA activity and reduce HPA reactivity to acute stress in pre-pubertal children [42]. In cancer patients, moderate chronic PA positively influences sleep behaviour and the activity–wake circadian rhythm [43]. As lower cortisol secetion in daytime may act as a protective factor due to prior over-stimulated HPA axis in obesity [25], a reduction in morning cortisol concentrations and daytime cortisol output may also contribute to the role of MVPA as a protective factor in response to chronic stress. In both adults and children, traditional research has mainly focused on a single exercise or unclassified physical activity, without consideration of the combined effects of the composition of the rest of the day. In this study, we eliminated such drawbacks and emphasized the important role of the proportion of time spent in MVPA in the circadian system.

Our findings also suggest that increased non-screen sedentary behaviours and inadequate sleep duration are associated with higher night-time cortisol output. With sleep loss, cortisol may exert its deleterious metabolic effects by maintaining high night-time concentrations, which are associated with insulin resistance (IR), suppressed immunity and increased inflammation [44]. Thus, the findings of this integrated approach indicate that the relative distribution of time spent in different physical activities within a 24-h period is important for health promotion and maintenance of diurnal cortisol rhythm in the paediatric population.

Flat slopes with lower amplitude, i.e., those exhibiting suppressed peak levels or failing to reach sufficiently low levels by evening, are indicative of HPA dysregulation [45] and associated with a higher risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [17, 25]. As the circadian system also plays a role in modulating appetite with self-reported hunger peaks at night [46], elevated nadir cortisol may further increase appetite and promote the consumption of foods enriched in fat and sugar at night [13]. Moreover, fasting glucose is supposed to be lowest at night, and glucose elevation at night has been demonstrated to be temporally and quantitatively correlated with cortisol rise [47]. Human explant visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue clock gene expression rhythms can be altered by dexamethasone administration [48]. In light of this, an interaction pathway with the HPA axis to mediate food intake and body weight via the circadian output of adipocytes is postulated [49]. In the present study, there were no associations between cortisol rhythms and glucose or lipid metabolism due to the non-corresponding sampling time to verify the above hypothesis. Nonetheless, metabolic disorders in children with obesity were increased compared with those in normal weight children (data not shown). Further analysis is warranted to verify this pattern and assess the relationship between obesity complications and cortisol slope.

Here, we present a preliminary study that examined the relationship between indices of salivary cortisol and the clinical characteristics of children and adolescents. Nonetheless, some limitations should be noted. Socioeconomic status index, dietary data and growth hormone levels were not included, and these factors may be related to cortisol rhythms. Moreover, the small sample size and sampling time limited additional findings, especially regarding verification of the correlations of cortisol rhythms with lipid and glucose metabolism. Finally, the level and intensity of PA, SB and sleep duration were parent- or self-reported, and these subjective measurements might confound the results.

Conclusion

This study offers initial insight into the complex and interrelated associations of diurnal cortisol rhythm and obesity during childhood and adolescence. We demonstrated reduced cortisol levels in the morning and increased levels at night in childhood obesity. Flatter and less sharply declining slopes correlated with adiposity, indicating an alteration in the circadian rhythm of cortisol with adiposity. Our findings also support the importance of an appropriate distribution of 24-h movement for optimal health and the circadian system in children and young people. Synchronizing exercise and nutrient interventions to the circadian clock might maximize the health-promoting benefits of interventions to prevent and treat metabolic disease [50]. Thus, chronotherapeutic approaches targeting the maintenance of normal rhythms via a healthy lifestyle may be effective in counteracting obesity and other metabolic diseases in children and adolescents.

Availability of data and materials

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

- AUC:

-

Areas under the curve

- DCS:

-

Diurnal cortisol slope

- ECLIA:

-

Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay

- FM%:

-

Fat mass percentage

- FG:

-

Fasting glucose

- FI:

-

Fasting insulin

- HOMA-IR:

-

The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- MPA:

-

Moderate-intensity physical activities

- HPA axis:

-

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- SB:

-

Sedentary behaviours

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- VPA:

-

Vigorous-intensity physical activities

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHtR:

-

The waist-to-height ratio

References

Fang X, Zuo J, Zhou J, Cai J, Chen C, Xiang E, et al. Childhood obesity leads to adult type 2 diabetes and coronary artery diseases: a 2-sample mendelian randomization study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(32):e16825.

Kumar S, Kelly AS. Review of childhood obesity: from epidemiology, etiology, and comorbidities to clinical assessment and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(2):251–65.

Simon SL, Behn CD, Cree-Green M, Kaar JL, Pyle L, Hawkins SMM, et al. Too late and not enough: school year sleep duration, timing, and circadian misalignment are associated with reduced insulin sensitivity in adolescents with overweight/obesity. J Pediatr. 2019;205:257–264.e251.

Pereira LR, Moreira FP, Reyes AN, Bach SL, Amaral PLD, Motta JDS, et al. Biological rhythm disruption associated with obesity in school children. Childhood Obes (Print). 2019;15(3):200–5.

Kolbe I, Dumbell R, Oster H. Circadian clocks and the interaction between stress Axis and adipose function. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:693204.

Bjorntorp P. Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities? Obes Rev. 2001;2(2):73–86.

Garbellotto GI, Reis FJ, Feoli AMP, Piovesan CH, Gustavo ADS, Oliveira MDS, et al. Salivary cortisol and metabolic syndrome Component's association. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2018;31(1):e1351.

Gamble KL, Berry R, Frank SJ, Young ME. Circadian clock control of endocrine factors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(8):466–75.

Porter J, Blair J, Ross RJ. Is physiological glucocorticoid replacement important in children? Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(2):199–205.

Vitale JA, Lombardi G, Weydahl A, Banfi G. Biological rhythms, chronodisruption and chrono-enhancement: the role of physical activity as synchronizer in correcting steroids circadian rhythm in metabolic dysfunctions and cancer. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35(9):1185–97.

Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, McQuillan MT, Dahlke KA, Gilbert KE. Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;83:25–41.

Elder GJ, Wetherell MA, Barclay NL, Ellis JG. The cortisol awakening response--applications and implications for sleep medicine. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(3):215–24.

Hewagalamulage SD, Lee TK, Clarke IJ, Henry BA. Stress, cortisol, and obesity: a role for cortisol responsiveness in identifying individuals prone to obesity. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2016;56(Suppl):S112–20.

Hillman JB, Dorn LD, Loucks TL, Berga SL. Obesity and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in adolescent girls. Metab Clin Exp. 2012;61(3):341–8.

Kumari M, Chandola T, Brunner E, Kivimaki M. A nonlinear relationship of generalized and central obesity with diurnal cortisol secretion in the Whitehall II study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4415–23.

Al-Safi ZA, Polotsky A, Chosich J, Roth L, Allshouse AA, Bradford AP, et al. Evidence for disruption of normal circadian cortisol rhythm in women with obesity. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34(4):336–40.

Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Epel ES, White ML, Standen EC, Seckl JR, Tomiyama AJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and cortisol activity in obesity: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:301–18.

Kjolhede EA, Gustafsson PE, Gustafsson PA, Nelson N. Overweight and obese children have lower cortisol levels than normal weight children. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103(3):295–9.

Barat P, Gayard-Cros M, Andrew R, Corcuff JB, Jouret B, Barthe N, et al. Truncal distribution of fat mass, metabolic profile and hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis activity in prepubertal obese children. J Pediatr. 2007;150(5):535–539.e531.

WHO. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age. Methods and development; 2006.

Balzer BWR, Garden FL, Amatoury M, Luscombe GM, Paxton K, Hawke CI, et al. Self-rated Tanner stage and subjective measures of puberty are associated with longitudinal gonadal hormone changes. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019;32(6):569–76.

Turpeinen U, Hamalainen E. Determination of cortisol in serum, saliva and urine. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(6):795–801.

Blair J, Adaway J, Keevil B, Ross R. Salivary cortisol and cortisone in the clinical setting. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24(3):161–8.

Derr RL, Cameron SJ, Golden SH. Pre-analytic considerations for the proper assessment of hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary Axis in epidemiological research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(3):217–26.

Champaneri S, Xu X, Carnethon MR, Bertoni AG, Seeman T, DeSantis AS, et al. Diurnal salivary cortisol is associated with body mass index and waist circumference: the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(1):E56–63.

Rotenberg S, McGrath JJ, Roy-Gagnon MH, Tu MT. Stability of the diurnal cortisol profile in children and adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(12):1981–9.

Werner H, Lebourgeois MK, Geiger A, Jenni OG. Assessment of chronotype in four- to eleven-year-old children: reliability and validity of the Children's Chronotype questionnaire (CCTQ). Chronobiol Int. 2009;26(5):992–1014.

Huang YJ, Wong SH, Salmon J. Reliability and validity of the modified Chinese version of the Children's leisure activities study survey (CLASS) questionnaire in assessing physical activity among Hong Kong children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2009;21(3):339–53.

Devaney J, Chastin SFM, Palarea-Albaladejo J, Dontje ML, Skelton DA. Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio-metabolic health markers: a novel compositional data analysis approach. PLoS One. 2015;1:10.

Bergman P, Carson V, Tremblay MS, Chaput J-P, McGregor D, Chastin S. Compositional analyses of the associations between sedentary time, different intensities of physical activity, and cardiometabolic biomarkers among children and youth from the United States. PLoS One. 2019;14:7.

Carson V, Tremblay MS, Chaput JP, Chastin SF. Associations between sleep duration, sedentary time, physical activity, and health indicators among Canadian children and youth using compositional analyses. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6 Suppl 3):S294–302.

King LS, Colich NL, LeMoult J, Humphreys KL, Ordaz SJ, Price AN, et al. The impact of the severity of early life stress on diurnal cortisol: the role of puberty. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;77:68–74.

Duan XN, Yan SQ, Wang SM, Hu JJ, Fang J, Gong C, et al. Developmental characteristics of circadian rhythms in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during puberty. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi. 2018;39(8):1086–90.

Buren J, Bergstrom SA, Loh E, Soderstrom I, Olsson T, Mattsson C. Hippocampal 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 messenger ribonucleic acid expression has a diurnal variability that is lost in the obese Zucker rat. Endocrinology. 2007;148(6):2716–22.

Steptoe A, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Brydon L, Wardle J. Central adiposity and cortisol responses to waking in middle-aged men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(9):1168–73.

Abraham SB, Rubino D, Sinaii N, Ramsey S, Nieman LK. Cortisol, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study of obese subjects and review of the literature. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(1):E105–17.

Chu L, Shen K, Liu P, Ye K, Wang Y, Li C, et al. Increased cortisol and cortisone levels in overweight children. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2017;23:25–30.

Sun Y, Deng F, Liu Y, Tao FB. Cortisol response to psychosocial stress in Chinese early puberty girls: possible role of depressive symptoms. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:781241.

Adam EK. Transactions among adolescent trait and state emotion and diurnal and momentary cortisol activity in naturalistic settings. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(5):664–79.

Marceau K, Ruttle PL, Shirtcliff EA, Essex MJ, Susman EJ. Developmental and contextual considerations for adrenal and gonadal hormone functioning during adolescence: implications for adolescent mental health. Dev Psychobiol. 2015;57(6):742–68.

Shirtcliff EA, Dismukes AR, Marceau K, Ruttle PL, Simmons JG, Han G. A dual-axis approach to understanding neuroendocrine development. Dev Psychobiol. 2015;57(6):643–53.

Martikainen S, Pesonen AK, Lahti J, Heinonen K, Feldt K, Pyhala R, et al. Higher levels of physical activity are associated with lower hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis reactivity to psychosocial stress in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(4):E619–27.

Roveda E, Vitale JA, Bruno E, Montaruli A, Pasanisi P, Villarini A, et al. Protective effect of aerobic physical activity on sleep behavior in breast cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther. 2017;16(1):21–31.

Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Sleep, circadian rhythm and body weight: parallel developments. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(4):431–9.

Fries E, Dettenborn L, Kirschbaum C. The cortisol awakening response (CAR): facts and future directions. Int J Psychophysiol. 2009;72(1):67–73.

Scheer FA, Morris CJ, Shea SA. The internal circadian clock increases hunger and appetite in the evening independent of food intake and other behaviors. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(3):421–3.

Poggiogalle E, Jamshed H, Peterson CM. Circadian regulation of glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in humans. Metab Clin Exp. 2018;84:11–27.

Gómez-Abellán P, Díez-Noguera A, Madrid JA, Luján JA, Ordovás JM, Garaulet M. Glucocorticoids affect 24 h clock genes expression in human adipose tissue explant cultures. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e50435.

Tsang AH, Kolbe I, Seemann J, Oster H. Interaction of circadian and stress systems in the regulation of adipose physiology. Horm Mol Biol Clin Invest. 2014;19(2):103–15.

Gabriel BM, Zierath JR. Circadian rhythms and exercise — re-setting the clock in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(4):197–206.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Clinical Laboratory of Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University for their technical assistance.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81773421), Jiangsu Province Key Research and Social Development Program (BE2015607), and the Innovation Team of Jiangsu Health (CXTDA 2017035). The funders had no role in the study design or collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in writing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TY and XL conceived and carried out the experiments. TY and SW performed the data collection. TY performed the analyses. TY and XL wrote the paper. WZ, QL and XL reviewed the manuscript. All authors had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University Ethical Committee (NO.201603004–1). The parents provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, T., Zhou, W., Wu, S. et al. Evidence for disruption of diurnal salivary cortisol rhythm in childhood obesity: relationships with anthropometry, puberty and physical activity. BMC Pediatr 20, 381 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02274-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02274-8