Abstract

Background

There are scant data on the prevalence and clinical course of pertussis disease among infants with pneumonia in low- and middle-income countries. While pertussis vaccination coverage is high (≥90%) among infants in Botswana, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection affects nearly one-third of pregnancies.

We aimed to evaluate the prevalence and clinical course of pertussis disease in a cohort of HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU), HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU), and HIV-infected infants with pneumonia in Botswana.

Methods

We recruited children 1–23 months of age with clinical pneumonia at a tertiary care hospital in Gaborone, Botswana between April 2012 and June 2016. We obtained nasopharyngeal swab specimens at enrollment and tested these samples using a previously validated in-house real-time PCR assay that detects a unique sequence of the porin gene of Bordetella pertussis.

Results

B. pertussis was identified in 1/248 (0.4%) HUU, 3/110 (2.7%) HEU, and 0/33 (0.0%) HIV-infected children. All pertussis-associated pneumonia cases occurred in infants 1–5 months of age (prevalence, 1.0% [1/103] in HUU and 4.8% [3/62] in HEU infants). No HEU infants with pertussis-associated pneumonia were taking cotrimoxazole prophylaxis at the time of hospital presentation. One HUU infant with pertussis-associated pneumonia required intensive care unit admission for mechanical ventilation, but there were no deaths.

Conclusions

The prevalence of pertussis was low among infants and young children with pneumonia in Botswana. Although vaccination against pertussis in pregnancy is designed to prevent classical pertussis disease, reduction of pertussis-associated pneumonia might be an important additional benefit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pertussis is a respiratory illness most commonly caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease is classically divided into catarrhal, paroxysmal, and convalescent stages. The paroxysmal stage is classical of pertussis and manifests as intense bouts of coughing which may be interrupted by a high-pitched “whoop” as the child rapidly inhales. However, paroxysmal cough may be absent in young infants, and pertussis disease in infancy can be complicated by apnea, convulsions, and death [1].

The burden of pertussis disease in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is difficult to estimate and poorly recorded. This may be due to the limited availability of diagnostic assays for B. pertussis detection and under recognition of pertussis infection that is not associated with classical clinical features [2]. Several factors that might affect the risk and severity of pertussis disease among infants merit special consideration in LMICs. Of particular concern is maternal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, which is estimated to affect nearly one-third of pregnancies in Botswana and several other countries in sub-Saharan Africa [3]. HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) infants are at higher risk of severe infections [4] and have lower anti-pertussis antibodies at birth than the infants of HIV-negative mothers (HIV-unexposed uninfected; HUU) [5].

There are scant data on the prevalence and clinical course of pertussis among infants with pneumonia in LMICs because most studies selectively enrolled infants with clinical symptoms classically associated with pertussis (e.g., whooping cough). As infants and young children with pertussis disease often do not manifest these classical symptoms, restricting recruitment to patients with these symptoms has likely led to underestimation of pertussis disease prevalence. Furthermore, immunization against pertussis in pregnancy is being implemented in an increasing number of countries, with the primary goal of preventing classical pertussis disease among young infants [6]. However, an additional benefit of maternal pertussis immunization programs may be the reduction of pneumonia caused by pertussis. Thus, data on the prevalence and clinical course of pertussis-associated pneumonia are important in settings where immunization against pertussis during pregnancy is being considered.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence and clinical course of pertussis disease in a cohort of HUU, HEU, and HIV-infected infants and young children with pneumonia in Botswana.

Methods

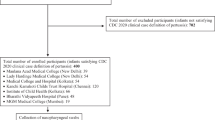

Study population

The study population was previously described in detail [7]. Briefly, we recruited children 1–23 months of age presenting with pneumonia at Princess Marina Hospital in Gaborone, Botswana between April 2012 and June 2016. We defined pneumonia per World Health Organization (WHO) clinical criteria as “cough or difficulty in breathing with lower chest wall indrawing” [7]. We excluded children with chronic medical conditions predisposing to pneumonia (except HIV infection), hospitalization within the previous 14 days, a diagnosis of asthma, or wheezing with resolution of chest wall indrawing after ≤2 treatments with a bronchodilator. Whole-cell pertussis (wP) vaccine is used for primary and booster immunization of infants and children in Botswana, with the primary series being administered at 2, 3, and 4 months of age. Women were not routinely immunized for pertussis during pregnancy in Botswana throughout the study period.

Laboratory methods

We obtained nasopharyngeal swab specimens from all children at enrollment using flocked swabs and universal transport media (Copan Italia, Brescia, Italy). Specimens were stored at − 80 °C, shipped on dry ice at 6-month intervals to the Regional Virology Laboratory (St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, ON, Canada), and tested for respiratory viruses using PCR [7]. In the analyses presented herein, we used a previously validated highly sensitive and specific in-house real-time PCR assay that detects a unique sequence of the porin gene of B. pertussis [8].

Results

B. pertussis was identified in 4/396 (1.0%) children with pneumonia, including 3/110 (2.7%) HEU children, 1/248 (0.4%) HUU children, and 0/33 (0.0%) HIV-infected children. All pertussis-associated pneumonia cases were among infants 1–5 months of age (Table 1). Among infants 1–5 months of age, the prevalence of B. pertussis was 1.0% (1/103) in HUU infants and 4.8% (3/62) in HEU infants. No HEU infants with pertussis-associated pneumonia were taking cotrimoxazole prophylaxis at the time of hospital presentation. Among HEU infants 1–5 months of age who tested negative for B. pertussis, 30/62 (48%) were taking cotrimoxazole at the time of presentation. Among the 20 HIV-infected children with data on cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, 9 (45%) were taking cotrimoxazole at the time of presentation.

Respiratory virus co-infection was detected in two infants with pertussis-associated pneumonia, including one infant with respiratory syncytial virus and one infant with rhinovirus B. One 4-month-old infant with pertussis-associated pneumonia had completed a 3-dose series of primary immunization against pertussis. None of the infants with pertussis-associated pneumonia received antibiotics active against B. pertussis during the hospitalization. One HUU infant with pertussis-associated pneumonia required intensive care unit admission for mechanical ventilation, but there were no deaths.

Discussion

B. pertussis was detected from only 1% of children less than 2 years of age with pneumonia in Botswana. However, among infants 1–5 months of age with pneumonia, the prevalence of B. pertussis was 2%, including a prevalence of approximately 5% among HEU infants in this age group. Pertussis-associated pneumonia was not associated with mortality in the few cases observed in this cohort. This study provides important data on the prevalence and clinical outcome of pertussis-associated pneumonia among infants and young children in a LMIC setting where surveillance for pertussis disease is lacking and wP vaccine is used for routine childhood immunization against pertussis.

The prevalence of B. pertussis among infants 1–5 months of age with pneumonia in this study is similar to the prevalence among infants 1–5 months of age (2.6%; 40/1547) and HEU infants aged 1–5 months of age (4.7%; 12/256) hospitalized with severe or very severe pneumonia in multiple African countries (The Gambia, Kenya, Mali, South Africa, Zambia) in the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) Study [9]. Our results are also similar to a study conducted in South Africa, where the prevalence of B. pertussis was 2.3% (42/1839) among infants < 12 months of age (95% of whom were < 6 months of age) and 2.7% (16/599) in HIV-exposed infants hospitalized with respiratory illnesses or neonatal sepsis [10]. However, we observed a lower prevalence of pertussis than was seen in a study of South African children < 13 years of age hospitalized with lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), in which the prevalence of B. pertussis was 7.0% (32/460) among all children (median age 8 months) and 10.9% (10/92) in HEU children [11].

Several factors may influence the prevalence of B. pertussis among infants in our cohort compared with previous studies. Vaccination coverage for three doses of pertussis vaccine is higher in Botswana than in South Africa (≥90% vs. 66%) [12], and ranges between 45 and 99% in other African countries [13]. Moreover, acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine is used in South Africa for primary immunization [9], while wP vaccine is used in Botswana and in most other African countries [13]. Children who receive wP vaccine have greater protection against pertussis disease than children who receive aP vaccine [14]. Moreover, we may have underestimated the prevalence of pertussis disease by using nasopharyngeal samples for microbiological diagnosis. In the aforementioned South African study [11], nearly half (47%) of pertussis cases were positive by PCR from induced sputum samples and negative by PCR from nasopharyngeal samples. In another study, induced sputum increased the diagnostic yield for B. pertussis over nasopharyngeal swabs alone by 18% among infants < 6 months of age with respiratory illnesses [15]. However, nasopharyngeal swabs are used more commonly than induced sputum for diagnostic testing in young infants, and our approach is likely to be representative of that used in clinical practice.

The prevalence of pertussis among infants 1–5 months of age was higher in HEU than HUU infants, but the small number of cases precluded meaningful statistical analysis. A difference would be theoretically plausible given previous data that HEU infants have lower anti-pertussis antibodies at birth compared with HUU infants [5]. Notably, none of the HEU infants < 6 months of age with pertussis-associated pneumonia were receiving cotrimoxazole prophylaxis at the time of presentation, but nearly half of infants who tested negative for B. pertussis were taking this medication.

Cotrimoxazole is a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent used to treat a range of bacteria as well as some fungi and protozoa and is a treatment option for pertussis disease. WHO guidelines recommend use of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for all infants of HIV-infected mothers, from 4 to 6 weeks of age until the end of HIV exposure and until HIV infection has been excluded [16]. However, these guidelines have been debated and the benefit of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis to HEU infants remains unclear [17, 18]. A recent trial did not find an overall survival benefit from cotrimoxazole prophylaxis among HEU infants in Botswana [19]. Cotrimoxazole has antimicrobial activity against a wide range of pathogens and its routine and widespread use could increase the development of bacterial resistance [20]. In addition, there is a potential risk of increasing sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum [21].

In this study, pertussis was not detected in any of the 33 HIV-infected infants with pneumonia. The transplacental transfer of anti-pertussis antibodies is reduced in HIV-infected women relative to HIV-uninfected women [22]. However, the clinical significance of this observation is unclear due to the lack of an established serum antibody level that provides clinical protection against pertussis disease. It is possible that the lower anti-pertussis antibody levels in HIV-exposed infants are still protective against pertussis disease. In addition, a proportion of HIV-infected infants (9/20 with available prophylaxis data) were on cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, which could have reduced their risk of B. pertussis infection.

Although the prevalence of pertussis among infants with pneumonia in this study is relatively low, identification of B. pertussis may still be of importance in young infants as pertussis disease can be complicated by apnea, convulsions, and death in this population [1]. Although not observed among the small number of infants with pertussis in this study, these complications might be evident at the population level. There are scarce and conflicting data regarding the effect of B. pertussis detection on the severity of LRTI among infants. The identification of B. pertussis among infants with LRTI was previously associated with a relatively mild clinical presentation and course compared to infants from whom B. pertussis was not detected [23]. However, in the PERCH Study, infants < 6 months of age with pertussis-associated pneumonia were more likely to have vomiting and high leukocyte counts (> 20,000 cells/μL) than infants with pneumonia who tested negative for pertussis [9].

Antibiotic treatment is indicated for all cases of pertussis, regardless of the clinical presentation or the severity of the illness. While treatment of pertussis early in the course of the disease is more likely to ameliorate symptoms than treatment later in the disease course [24], an additional benefit of treatment of pertussis disease is the reduction of person-to-person transmission [25,26,27]. Interrupting transmission is an important public health benefit because there is high prevalence of subclinical or mild infections among household contacts of pertussis cases, which may play a critical role in the maintenance of ongoing transmission of pertussis [27].

Immunization against pertussis in pregnancy has been shown to decrease the risk of pertussis infection and the severity of pertussis disease among young infants [28, 29]. An additional benefit to pertussis immunization in pregnancy may be the prevention of illnesses that are not classically associated with pertussis. Given that pertussis vaccination in pregnancy is highly effective (~ 85% efficacy) in preventing pertussis disease among young infants [29], it is also reasonable to anticipate that the majority of pertussis-associated pneumonia cases in this study could have been prevented by pertussis immunization in pregnancy.

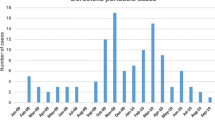

This study has a number of strengths. B. pertussis was tested for in a large number of infants with pneumonia in an African country with long-standing high uptake of the wP vaccine. The study was prospective and conducted over 5 years, thus minimizing the possibility that seasonal variation and the cyclical pattern of pertussis might influence the results. This study also has several important limitations. It was conducted at a single referral center and the results may not be generalizable to non-tertiary care centers. Furthermore, patients with more severe pneumonia may have died before admission to hospital, and consequently some cases of pertussis may have been missed. The small sample size of HIV-infected infants limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions about the prevalence of B. pertussis among infants with pneumonia in this population. Finally, the study did not include infants < 1 month of age, an age group that is highly susceptible to severe pertussis infection.

Conclusion

The prevalence of pertussis was low among infants and young children with pneumonia in Botswana. The limited data on the burden of pertussis in young infants in LMICs is a major obstacle to determining if vaccination against pertussis in pregnancy warrants implementation in such settings. Although vaccination against pertussis in pregnancy is designed to prevent classical pertussis disease, reduction of pertussis-associated pneumonia might be an important additional benefit.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- aP:

-

Acellular pertussis

- HEU:

-

HIV-exposed uninfected

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HUU:

-

HIV-unexposed uninfected

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- LRTI:

-

Lower respiratory tract infection

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- wP:

-

Whole-cell pertussis

References

Kilgore PE, Salim AM, Zervos MJ, Schmitt HJ. Pertussis: microbiology, disease, treatment, and prevention. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29(3):449–86.

Mooi FR, de Greeff SC. The case for maternal vaccination against pertussis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(9):614–24.

World health organization. http://www.who.int/hiv/HIVCP_BWA.pdf. Accessed 23 Oct 2017.

Slogrove AL, Goetghebuer T, Cotton MF, Singer J, Bettinger JA. Pattern of infectious morbidity in HIV-exposed uninfected infants and children. Front Immunol. 2016;7:164.

Abu-Raya B, Smolen KK, Willems F, Kollmann TR, Marchant A. Transfer of maternal antimicrobial immunity to HIV-exposed uninfected newborns. Front Immunol. 2016;7:338.

Abu Raya B, Edwards KM, Scheifele DW, Halperin SA. Pertussis and influenza immunisation during pregnancy: a landscape review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(7):e209–e22.

Kelly MS, Smieja M, Luinstra K, Wirth KE, Goldfarb DM, Steenhoff AP, et al. Association of respiratory viruses with outcomes of severe childhood pneumonia in Botswana. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126593.

Hasan MR, Tan R, Al-Rawahi GN, Thomas E, Tilley P. Evaluation of amplification targets for the specific detection of Bordetella pertussis using real-time polymerase chain reaction. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2014;25(4):217–21.

Barger-Kamate B, Deloria Knoll M, Kagucia EW, Prosperi C, Baggett HC, Brooks WA, et al. Pertussis-associated pneumonia in infants and children from low- and middle-income countries participating in the PERCH study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(suppl 4):S187–S96.

Soofie N, Nunes MC, Kgagudi P, van Niekerk N, Makgobo T, Agosti Y, et al. The burden of pertussis hospitalization in HIV-exposed and HIV-unexposed south African infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(suppl 4):S165–S73.

Muloiwa R, Dube FS, Nicol MP, Zar HJ, Hussey GD. Incidence and diagnosis of pertussis in south African children hospitalized with lower respiratory tract infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(6):611–6.

World Health Organization. Summary country profile for HIV/AIDS treatment scale up. http://www.who.int/hiv/HIVCP_BWA.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2019.

Muloiwa R, Wolter N, Mupere E, Tan T, Chitkara AJ, Forsyth KD, et al. Pertussis in Africa: findings and recommendations of the global pertussis initiative (GPI). Vaccine. 2018;36(18):2385–93.

Sheridan SL, Ware RS, Grimwood K, Lambert SB. Reduced risk of pertussis in whole-cell compared to acellular vaccine recipients is not confounded by age or receipt of booster-doses. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5027–30.

Nunes MC, Soofie N, Downs S, Tebeila N, Mudau A, de Gouveia L, et al. Comparing the yield of nasopharyngeal swabs, nasal aspirates, and induced sputum for detection of Bordetella pertussis in hospitalized infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(suppl 4):S181–S6.

Joint WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF. Statement on use of cotrimoxazole as prophylaxis in HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children [press release]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Coutsoudis A, Coovadia HM, Kindra G. Time for new recommendations on cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-exposed infants in developing countries? Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(12):949–50.

Evans C, Prendergast AJ. Co-trimoxazole for HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(5):e468–e9.

Lockman S, Hughes M, Powis K, Ajibola G, Bennett K, Moyo S, et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole on mortality in HIV-exposed but uninfected children in Botswana (the Mpepu study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(5):e491–500.

Martin JN, Rose DA, Hadley WK, Perdreau-Remington F, Lam PK, Gerberding JL. Emergence of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance in the AIDS era. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(6):1809–18.

Gill CJ, Sabin LL, Tham J, Hamer DH. Reconsidering empirical cotrimoxazole prophylaxis for infants exposed to HIV infection. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(4):290–7.

Jones CE, Naidoo S, De Beer C, Esser M, Kampmann B, Hesseling AC. Maternal HIV infection and antibody responses against vaccine-preventable diseases in uninfected infants. JAMA. 2011;305(6):576–84.

Abu Raya B, Bamberger E, Kassis I, Kugelman A, Srugo I, Miron D. Bordetella pertussis infection attenuates clinical course of acute bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(6):619–21.

Tiwari T, Murphy TV, Moran J, National Immunization Program CDC. Recommended antimicrobial agents for the treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis: 2005 CDC guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-14):1–16.

Altunaiji S, Kukuruzovic R, Curtis N, Massie J. Antibiotics for whooping cough (pertussis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD004404.

Langley JM, Halperin SA, Bouçher FD, Smith B. Azithromycin is as effective as and better tolerated than erythromycin estolate for the treatment of pertussis. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):e96–101.

Wood N, McIntyre P. Pertussis: review of epidemiology, diagnosis, management and prevention. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2008;9(3):201–11 quiz 11-2.

Winter K, Cherry JD, Harriman K. Effectiveness of prenatal tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination on pertussis severity in infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(1):9–14.

Winter K, Nickell S, Powell M, Harriman K. Effectiveness of prenatal versus postpartum tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination in preventing infant pertussis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(1):3-8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Copan Italia (Brescia, Italy) for their generous donation of the universal transport media and flocked swabs used for the collection of nasopharyngeal specimens. We offer our sincere thanks to the children and families who participated in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by an European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases Small Grant Award (to BA), an Early Career Award from the Thrasher Research Fund (to MSK), a Burroughs Wellcome / American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Postdoctoral Fellowship in Tropical Infectious Diseases (to MSK), and through core services from the Penn Center for AIDS Research, a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded program (P30-AI045008) and the Duke CFAR (5P30 AI064518). Funding for this project was also made possible in part by a CIPHER grant (to MSK) from the International AIDS Society, supported by ViiV Healthcare. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the International AIDS Society or ViiV Healthcare.

The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, or writing the manuscript. BA is supported by the Canadian Health and Research Institute Vanier Canada Graduate scholarship. MSK was supported by a NIH Career Development Award (K23-AI135090). MSa is supported via salary awards from the BC Children’s Hospital Foundation, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BA, DMG, MSm, KL, MRG, APF, KAF, TAM, CKC, SSS, MZP, MSK and MSa contributed significantly to the study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation. MSm, KL and MRG contributed significantly to the laboratory analysis. BA, MSK and MSa contributed significantly to the generation of the first manuscript draft. BA, DMG, MSm, KL, MRG, APF, KAF, TAM, CKC, SSS, MZP, MSK and MSa critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the relevant committees at the Botswana Ministry of Health Botswana, the University of British Columbia, Princess Marina Hospital, the University of Pennsylvania, and McMaster University. Written informed consent was obtained from a legal guardian for collection of the nasopharyngeal samples and clinical data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. MSa is an associate editor of BMC Pediatrics.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Abu-Raya, B., Goldfarb, D.M., Smieja, M. et al. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of pertussis-associated pneumonia among infants in Botswana. BMC Pediatr 19, 444 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1820-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1820-0