Abstract

Background

Congenital orbital teratoma is relatively rare, and few reports of prenatal ultrasound findings in such cases have been published.

Case presentation

A rare case of congenital orbital teratoma at 24 + 2 weeks of gestation was previously diagnosed as microphthalmia, noting how orbital teratoma without proptosis is different from microphthalmia, retinoblastoma and intracranial teratoma. Ultrasound examination, analysis of gross specimens, and histopathological evaluation confirmed the diagnosis of orbital teratoma.

Conclusion

Prenatal ultrasound examination is useful for diagnosis and differential diagnosis of congenital orbital teratoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Congenital orbital teratoma is relatively rare. These lesions are classified as mature or immature teratomas based on their degree of cellular differentiation. Orbital teratomas have been detected at birth or, more commonly, early in life due to clinical proptosis [1]. Nevertheless, foetal information is limited. Here, we report a prenatal case of mature orbital teratoma without proptosis at 24 + 2 weeks of gestation, with an initial diagnosis of microphthalmia. We present the ultrasound characteristics, gross specimens, and histopathological appearance.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old pregnant woman, gravida 1, para 0, at 24 + 2 weeks of gestation was referred to our department for prenatal ultrasound examination. Prenatal ultrasound examination revealed that the foetus’ eyes were asymmetrical. The right and left eye globes measured 10.9 × 8.3 mm and 6.8 × 6.0 mm, respectively. The mean normal foetal orbital diameter is 11.0 mm at 24 weeks of gestation [2]. An initial diagnosis of microphthalmia was made. A hyperechoic lesion was detected in the left retro-orbital space. The lesion was crescent shaped, with a maximum thickness of about 1.6 mm (Fig. 1b); it was confined to the orbit and showed no proptosis. No shadowing calcifications were detected. Colour Doppler ultrasound examination demonstrated significant angiogenesis in the lesion (Fig. 1a). Prenatal ultrasound examinations showed no structural abnormalities other than asymmetry of the eyes, and the intracranial structure did not appear to be deformed. The head circumference, abdominal circumference and femur length were consistent with the gestational age.

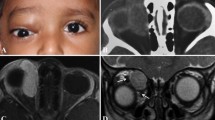

After consultation, the patient and her husband indicated that they wanted to induce labour. Autopsy demonstrated a normal facial appearance (image could be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author).

Histopathological examination showed a mature orbital teratoma in the retro-orbital space (Fig. 2). The teratoma was predominantly benign, with mature tissue originating in the ectoderm (epidermis and its derivatives), mesoderm (fatty tissue, blood vessels), and endoderm (gastrointestinal epithelium) (Fig. 2a). On immunohistochemical examination, the gland origin was confirmed by cytokeratin (CK) immunopositivity (Fig. 2b). The mesenchymal tissue showed diffuse and strong positive immunostaining for vimentin (Fig. 2c). In the mature parts of the teratoma, the cell proliferation rate determined using Ki-67 as a marker was about 10%, similarly to the level of normal tissue (Fig. 2d). Glypican-3 (GPC-3) and neuron specific enolase (NSE) staining were negative.

Histopathology of the tumour specimen. The vitreum is on the right of a. Islands of tumour tissue were detected in the retro-orbital space. The tumour contained skin and skin appendages (1), vascular tissue cells (2), fatty tissue (3), and differentiated mature glands (4). Strong, diffuse membrane immunohistochemical staining for CK indicated skin and skin appendages (b) and immunostaining for vimentin confirmed differentiated mature glands (c). The Ki-67 nuclear staining index was approximately 10% (d). Scale bars: Fig. a, 4 mm; Fig. a1–a4, 100 μm; b, c, d, 20 μm

Discussion and conclusion

Congenital orbital teratomas are quite rare. They are often reported in female infants and children with characteristic proptosis [1,2,3]. However, information on foetal cases is very limited (see Table 1). In our case, orbital teratoma was detected at 24 + 2 weeks of gestation, and the lesion was confined to the orbit without proptosis. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a foetal orbital teratoma without proptosis. Anami et al. [4] reported a large orbital teratoma with proptosis at 27 weeks and intrauterine foetal death at 32 weeks of gestation. We suspect that the absence of proptosis in our case was because the disease was in its early stage. Although orbital teratoma is often associated with rapid enlargement soon after birth [3, 5], the absence of proptosis can lead to confusion and a delay in diagnosis. Therefore, screening of the retro-orbital space is essential for diagnosis of orbital teratoma, especially in cases without proptosis.

Firstly, as this case had no proptosis and asymmetrical eyes, it was initially misdiagnosed as microphthalmia, the most likely cause of small eyes. Orbital teratoma and microphthalmia can be distinguished by three differences. First, microphthalmia is more commonly bilateral. The exception appears to be isolated microphthalmia, which is usually unilateral. Microphthalmia shows no predominance with regards to gender, while orbital teratomas are usually unilateral and more often seen in females. Second, microphthalmia results in a small orbit volume compared to age-matched controls [10], whereas orbital teratoma results in enlarged, remodelled, or destroyed orbit [11]. Finally, in microphthalmia, ultrasound examination does not show blood flow signals in the orbit. In contrast, colour Doppler ultrasound shows a clear blood flow signal in the lesion in the present case of orbital teratoma [4]. In microphthalmia patients, the potential for visual development depends on the degree of retinal development and other ocular characteristics. Therapy aims to maximise existing vision and enhance cosmetic appearance rather than improve sight [10]. In orbital teratoma patients, timely and accurate diagnosis enables early surgical resection of the orbital teratoma with satisfactory cosmetic results, consisting of preservation of the eyeball and visual function [12]. The prenatal orbital diagnosis of teratoma is important to allow timely counselling of the parents and as an aid in obstetric decision making.

In addition, retinoblastoma as the most common intraocular malignancy of infancy and childhood demonstrates a mass more echogenic than the vitreous, with fine calcifications by ultrasonography. Retinal detachment may also be observed in exophytic forms [13]. While the orbital was always in normal values scale without mass effecting the retro-orbital space [14, 15].

Finally, intracranial teratoma invading the orbit may not cause proptosis. Arslan et al. [16] reported a large intracranial immature teratoma extending into the retro-orbital space. In the present case, the lesion was located in the retro-orbital space, and the foetal intracranial structure was normal.

In conclusion, screening of the retro-orbital space is essential for diagnosis of orbital teratoma. And it is important to perform colour Doppler ultrasound and screening of intracranial structures in cases of abnormal orbital lesions. These findings suggest that prenatal ultrasound examination should play a critical role in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of orbital teratoma.

Availability of data and materials

The data and images used or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CK:

-

cytokeratin

- GPC-3:

-

Glypican-3

- NSE:

-

neuron specific enolase

- MRI:

-

nuclear magnetic resonance

- US:

-

ultrasonography

References

Mehta M, Chandra M, Sen S, Bajaj MS, Pushker N, Meel R, Ghose S. Orbital teratoma: a rare cause of congenital proptosis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;37(6):626–8.

Goldstein I, Tamir A, Zimmer EZ, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Growth of the fetal orbit and lens in normal pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12(3):175–9.

Khadka S, Shrestha GB, Gautam P, Shrestha JB. Orbital Teratoma: a rare congenital tumour. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2017;9(18):79–82.

Anami A, Fukushima K, Fujita Y, Satoh S, Matsumoto E, Endo M, Oda Y, Wake N. Antenatally diagnosed congenital orbital teratoma in which rupture was associated with intrauterine fetal death. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(3):578–81.

Alkatan HM, Chaudhry I, Alayoubi A. Mature teratoma presenting as orbital cellulitis in a 5-month-old baby. Ann Saudi Med. 2013;33(6):623–6.

Herman TE, Vachharajani A, Siegel MJ. Massive congenital orbital teratoma. J Perinatol. 2009;29(5):396–7.

Moon YJ, Hwang HS, Kim YR, Park YW, Kim YH. Prenatally detected congenital orbital teratoma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31(1):107–9.

Mamalis N, Garland PE, Argyle JC, Apple DJ. Congenital orbital teratoma: a review and report of two cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 1985;30(1):41–6.

More GHM, Vieira J, Akaishi PMS, Cruz AAV. Orbital Teratoma: MRI changes from fetal life to Exenteration. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(2):e58.

Verma AS, Fitzpatrick DR. Anophthalmia and microphthalmia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:47.

Sesenna E, Ferri A, Thai E, Magri AS. Huge orbital teratoma with intracranial extension: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(5):e27–31.

Kominek M, Autrata R, Krejcirova I, Senkova K, Zajdlikova B, Pernicova K, Masarikova A, Jezova M. Primary orbital teratoma - case study. Ceska Slovenska Oftalmologie. 2019;75(1):40–4.

Aerts I, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Gauthier-Villars M, Brisse H, Doz F, Desjardins L. Retinoblastoma. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:31.

Friang C, Caputo G, Freneaux P, Lecler A. Teaching NeuroImages: a diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma. Neurology. 2018;90(4):e357–8.

Brisse HJ, Lumbroso L, Fréneaux PC, Validire P, Doz FP, Quintana EJ, Berges O, Desjardins LC, Neuenschwander SG. Sonographic, CT, and MR imaging findings in diffuse infiltrative retinoblastoma: report of two cases with histologic comparison. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(3):499–504.

Arslan E, Usul H, Baykal S, Acar E, Eyuboglu EE, Reis A. Massive congenital intracranial immature teratoma of the lateral ventricle with retro-orbital extension: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43(4):338–42.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X C and J Z drafted the work and substantively revised it. GN H, JX Y, and CL C performed the ultrasound diagnosis and designed the work.CG Z, HL W and LH H collected and interpreted the patient data. L C performed the microbiological diagnosis and ZR Y helped analyzing data in this process. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the Sichuan Provincial Hospital for Women and Children waived the requirement for formal approval in this case. Full consent for the procedures described was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The data and images used or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Yang, J., He, G. et al. Orbital teratoma in the foetus: a rare case without proptosis. BMC Ophthalmol 20, 415 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01681-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01681-w