Abstract

Background

Suprachoroidal haemorrhage is a rare complication of either medical anticoagulation treatment or intraocular surgical procedures. Suprachoroidal haemorrhages often have devastating visual outcome despite conservative and/or surgical intervention.

Case presentation

A patient with known Open Angle Glaucoma and Atrial Fibrillation on warfarin presents symptoms and signs suggestive acute angle closure. Examination reveals the underlying cause is a large, macula involving, spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage secondary to loss of anti-coagulation control. Following aggressive medical treatment and surgical intervention, including drainage combined cataract extraction with intraocular lens implant, pars-plana vitrectomy, and external drainage of suprachoroidal haematoma, we managed to preserve the patient’s eye and some of its function.

Conclusion

Spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhages are rare complications of loss of anticoagulation control. Our case shows that aggressive treatment in selected cases can offer a relatively good outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Suprachoroidal haemorrhage is a rare complication of intraocular surgery or trauma. Even more rarely it may be spontaneous. Risk factors include older age, patients on systemic anticoagulation, systemic hypertension, atherosclerosis, age-related macular degeneration and chronic kidney disease. When they occur, Suprachoroidal haemorrhages often have devastating visual outcome despite conservative and/or surgical intervention [1,2,3].

Case presentation

We present a case of acute angle closure due to spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage secondary to loss of anti-coagulation control.

A 67-year-old man, who recently returned from a holiday abroad, presented with a one-day history of worsening right visual acuity and 4 day history of increasing right retro-bulbar pain not relieved with simple analgesia.

He had a past medical history of essential tremor managed with Propranolol, Atrial Fibrillation on anticoagulation with Warfarin 4 mg daily – target International Normalised Ratio (INR) 2.5. Possible confusion with his tablets in the week leading up to the start of his symptoms.

Our patient was also known to have normal tension glaucoma (NTG) managed with Latanoprost. He had Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty (SLT) to the right eye 12 months before to improve his intraocular pressure control. His last recorded visual acuity (VA) was 6/6 in both eyes.

On examination the patient was found to have reduced VA in the right eye 6/12 with an injected conjunctiva, cloudy cornea and a mid-dilated pupil with a very shallow anterior chamber (AC) and closed irido-corneal angle on gonioscopy (Figs. 1 and 2). Fundus exam revealed a large supero-nasal suprachoroidal haemorrhage not involving the macula. His right intra-ocular pressure (IOP) was 42 mmHg. The left eye had a VA of 6/6 with a deep AC and IOP of 12 mmHg (Fig. 3). He was therefore diagnosed with acute angle closure secondary to spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage. His INR measured at > 8. The patient was given 1 mg of Vitamin K to reverse his INR, which quickly came down to 5.1. Advice was taken from the general physicians’ team and no further Vitamin K doses were given.

He was started on maximal topical and systemic IOP lowering treatment including G. Apraclonidine 1% TDS, G. Latanoprost 0.005% ON, G. Brinzolamide/Timolol (Azarga®) and Oral Acetaolamide 250 mg QDS as well as cycloplegia with G. Atropine 1% OD.

After 12 h the IOP was 27 mmHg and INR 3.1. But unfortunately, in the following 12 h, the patient had a second bleed, and his IOP went up to 42 mmHg and VA was down to finger counting. There was no view of the fundus due to corneal edema. B-Scan Ultrasound showed an extension of the suprachoroidal haemorrhage, covering 360 degrees and involving the fovea (Fig. 4).

For the next 7 days the patient’s remained on the same medical treatment and his IOP was stable in the high 20s. A decision was taken to perform a combined phacoemulsification and lens implant, pars-plana vitrectomy and suprachoroidal haematoma drainage under general anesthesia. (Additional file 1).

Additional file 1: Video of the combined phacoemulsification and lens implant, pars-plana vitrectomy and suprachoroidal haematoma drainage. (AVI 16420 kb)

Six weeks post operatively the patient had a wide-open angle with a central IOL and a flat retina (Figs. 5 and 6). Intraocular Pressure without IOP lowering treatment was recorded at 20 mmHg with VA 6/24. He was restarted on IOP lowering topical treatment (G Brinzolamide/Timolol BD).

Discussion

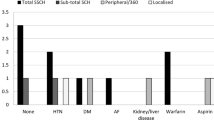

Subconjunctival haemorrhage, and to a lesser extent spontaneous hyphema are the most common ocular complications of loss of anti-coagulation control [4,5,6]. Spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage causing acute secondary angle-closure glaucoma is a rare ocular disorder [7]. The proposed mechanism for the angle-closure is the abrupt forward displacement of the lens-iris diaphragm, resulting from a massively detached choroid and retina. A similar mechanism also occurs with serous ciliochoroidal detachments in cases of uveal effusion syndrome, nanophthalmos, scleral buckling procedures, panretinal photocoagulation, central retinal vein obstruction, retinopathy of prematurity, scleritis, pars planitis, Harada’s disease, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and arteriovenous fistulas [8]. Posterior uveal melanoma can present with a spontaneous subretinal or intravitreal haemorrhage which can give rise to an acute or chronic angle closure glaucoma [9, 10].

In our patient, loss of coagulation control was due to confusion over two different tablets of the same color. He uses a Monitored Self Dosage (MSD) system, that he organizes himself, when he goes away from home for several days. We postulate that our patient made an error while organizing his MSD system prior to going on holiday. The consequence was inadvertent warfarin overdose, causing loss of anticoagulation control, which led to the spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage in the right eye.

Warfarin belongs to the Coumarin group of Vitamin K antagonists (VKA). It is the most commonly used VKA anticoagulant. Warfarin is usually reversed using systemic administration of vitamin K (commonly a single dose of 0.5 mg – 1 mg). However in cases of life or sight threatening haemorrhages, other agents are available to aided quicker control of coagulation. These are Prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC). Due to the rare nature of such severe bleeds within Ophthalmology practice, the option of PCC use was not considered initially. We can argue that the second haemorrhage could have been avoided if the INR was reversed more aggressively.

Conclusion

The case describes a rare entity of acute angle closure due to spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage secondary to loss of anti-coagulation control. Most of the previously reported cases of angle-closure glaucoma from massive hemorrhagic retinal or choroidal detachments have failed to respond to medical therapy and needed enucleation or retrobulbar injection treatment for pain [11,12,13]. Early recognition of this rare entity is vital in preserving the function of the eye. Aggressive medical and surgical treatment with suprachoroidal haematoma drainage offers some chance of preserving the eye and some of its function.

Abbreviations

- AC:

-

Anterior chamber

- INR:

-

International Normalised Ratio

- IOP:

-

Intra-ocular pressure

- MSD:

-

Monitored Self Dosage

- NTG:

-

Normal tension glaucoma

- OCT:

-

Optical coherence tomography

- PCC:

-

Prothrombin complex concentrate

- SLT:

-

Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty

- VA:

-

Visual acuity

- VKA:

-

Vitamin K antagonists

References

Chu TG, Green RL. Suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Surv Ophthalmol. 43:471–86. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10416790. Accessed 28 Nov 2016

De Marco R, Aurilia P, Mele A. Massive spontaneous choroidal hemorrhage in a patient with chronic renal failure and coronary artery disease treated with Plavix. Eur J Ophthalmol. 19:883–6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19787616. Accessed 28 Nov 2016

Yang SS, Fu AD, McDonald HR, Johnson RN, Ai E, Jumper JM. Massive spontaneous choroidal hemorrhage. Retina. 2003;23:139–44. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12707590. Accessed 28 Nov 2016

Holden R. Spontaneous hyphaema as a result of systemic anticoagulation in previously abnormal eyes. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67:1008–10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1775406. Accessed 28 Nov 2016

Koehler MP, Sholiton DB. Spontaneous hyphema resulting from warfarin. Ann Ophthalmol. 1983;15:858–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6660730. Accessed 28 Nov 2016

Kageler WV, Moake JL, Garcia CA. Spontaneous hyphema associated with ingestion of aspirin and ethanol. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;82:631–4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/970426. Accessed 28 Nov 2016

Gordon DM, Mead J. Retinal hemorrhage with visual loss during anticoagulant therapy: case report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16:99–100. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5634475. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Fourman S. Angle-closure glaucoma complicating ciliochoroidal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:646–53. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2664629. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Fraser DJ, Font RL. Ocular inflammation and hemorrhage as initial manifestations of uveal malignant melanoma. Incidence and prognosis. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill 1960). 1979;97:1311–4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/313204. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Yanoff M. Glaucoma mechanisms in ocular malignant melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;70:898–904. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5490617. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Cahn PH, Havener WH. Spontaneous massive choroidal hemorrhage. With preservation of the eye by sclerotomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1963;56:568–71. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14070707. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Wood WJ, Smith TR. Senile disciform macular degeneration complicated by massive hemorrhagic retinal detachment and angle closure glaucoma. Retina. 3:296–303. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6201973. Accessed 1 Dec 2016

Steinemann T, Goins K, Smith T, Amrien J, Hollins J. Acute closed-angle glaucoma complicating hemorrhagic choroidal detachment associated with parenteral thrombolytic agents. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:752–3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3195662. Accessed 1 Dec 2016.

Funding

This supplement and the meeting on which it was based were sponsored by Novartis (tracking number OPT17-C041). Novartis did not contribute to the content and all authors retained final control of the content and editorial decisions. Novartis have checked that the content was compliant with the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry Code of Practice.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Ophthalmology Volume 18 Supplement 1, 2018: The Novartis Ophthalmology Case Awards 2017. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcophthalmol.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-18-supplement-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IM authored the manuscript. SG, JMS and NKW proofread the manuscript. All authors were directly involved in the care of the patient. All authors read approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written consent for publication had been obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Masri, I., Smith, J.M., Wride, N.K. et al. A rare case of acute angle closure due to spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage secondary to loss of anti-coagulation control: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol 18 (Suppl 1), 224 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-018-0857-4

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-018-0857-4