Abstract

Background

Prognostic biomarkers provide essential information about a patient’s overall outcome. However, existing biomarkers are limited in terms of either sample collection, such as requiring tissue specimens, or the process, such as prolonged time for analysis. In view of the need for convenient and non-invasive prognostic biomarkers for oral cancer, we aimed to investigate the prognostic values of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patient survival. We also aimed to explore the associations of these ratios with the clinicopathologic characteristics of Japanese oral squamous cell carcinoma patients.

Methods

This study was a non-randomized retrospective cohort study in a tertiary referral center. We included 433 patients (246 men, 187 women) who underwent radical surgery for oral cancers between January 2001 and December 2013. We evaluated various risk factors for poor prognosis including neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio with univariate and multivariate analyses. The disease-specific survival and overall survival rates of patients were compared among the factors and biomarkers.

Results

In multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis, high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (hazard ratio 2.87, 95% confidence interval 1.59–5.19, P < 0.001), moderately or poorly differentiated histology (hazard ratio 2.37, 95% confidence interval 1.32–4.25, P < 0.001), and extranodal extension (hazard ratio 1.95, 95% confidence interval 1.13–3.35, P = 0.016) were independent predictors of disease-specific survival. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (hazard ratio 2.30, 95% confidence interval 1.42–3.72, P < 0.001), moderately or poorly differentiated (hazard ratio 1.72, 95% confidence interval 1.07–2.76, P = 0.025), and extranodal extension (hazard ratio 1.79, 95% confidence interval 1.13–2.84, P = 0.013) were independent predictors of overall survival.

Conclusions

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio might be a potential independent prognostic factor in Japanese oral squamous cell carcinoma patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common tumor of the head and neck region, and occurs predominantly in the oral cavity (90%) [1]. There have been recent improvements in the treatment of advanced OSCC. However, the survival of oral cancer patients has not dramatically improved [2]. Prognostic biomarkers are important for treatment because they provide essential information about the patients’ overall outcome. However, molecular biomarkers that need tissue specimens for analysis impose burden on patients, as it requires an invasive approach for sample collection. The analysis time for tissue biomarkers is also long. Therefore, there is an urgent need for convenient and non-invasive prognostic biomarkers for oral cancer.

It is well known that cancer has a close relationship with inflammation [3]. Inflammatory responses cause tumor progression such as initiation, progression, and metastasis [4]. The peripheral blood cell counts of the lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets are reported to be associated with prognosis in several cancers [5,6,7]. These values can be activated by oxidative stress, chemokines, and cytokines during cancer initiation and progression [8, 9]. One report suggested that leukocytes work differently in patients with cancer and those without [10]. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) are important hematological biomarkers and have been reported to be significant prognostic markers of head and neck cancer [11,12,13]. However, the results are controversial. Furthermore, few studies have quantitatively analyzed the usefulness of NLR, LMR, and PLR in predicting the prognosis in a small number of Japanese OSCC patients [14, 15].

In this study, we retrospectively investigated the prognostic values of NLR, LMR, and PLR in patient survival and their associations with the clinicopathologic characteristics of Japanese OSCC patients.

Methods

This was a non-randomized retrospective cohort study. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine and by the institutional review boards of the participating hospitals (Authorization number: 170086). The patient group included 433 patients (246 men, 187 women) who underwent radical surgery for OSCC between January 2001 and December 2013 at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Kobe University Hospital. The mean patient age was 66.3 ± 13.5 years (range: 22–98 years). The inclusion criteria were as follows: a histological diagnosis of OSCC and the presence of a previously untreated tumor scheduled for radical surgery at initial visit. Patients with factors that could influence the NLR, LMR, and PLR such as concurrent infections, chronic inflammatory diseases, chronic hematologic diseases, and recent treatment with steroids or immunosuppressive agents were also excluded.

The data assessed for each patient included the sex, age, smoking history, alcohol consumption, performance status (PS), subsite, clinical T classification (Union Internationale Contre le Cancer/American Joint Committee on Cancer [UICC/AJCC] staging system 7th edition), clinical N classification, histological grade (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, or poorly differentiated), surgical margins, number of pathologically metastatic lymph nodes, presence of pathologic extra nodal extension (ENE), and treatment outcome. The endpoints evaluated were; the disease-specific survival (DSS) rates as the primary outcome and the overall survival (OS) rates as the secondly outcome. Survival times were calculated from the date of surgery. The peripheral NLR was calculated as the ratio of the absolute peripheral neutrophil to lymphocyte count; the peripheral LMR was calculated as the ratio of the absolute peripheral lymphocyte to monocyte count, and the peripheral PLR was calculated as the ratio of the absolute peripheral platelet to lymphocyte count. The discriminatory ability of NLR, LMR, and PLR as possible indicators of DSS was evaluated with a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. This ROC curve was used to determine the cutoff values for clinical tests. The area under the resulting curve (AUC) measured the accuracy of the discrimination, ranging from 0.5 to 1. The cutoff value was chosen to minimize the number of false-positive and false-negative results. The patients were divided into two groups (the low group and high group) based on NLR, LMR, and PLR values. The DSS and OS rates of patients were compared among the patient characteristics including the NLR, LMR, and PLR.

The data were introduced into a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model in which patients were divided by age (≤ 64 years vs. ≥ 65 years), PS (0 vs. 1, 2, or 3), subsite (tongue vs. others), T stage (1 or 2 vs. 3 or 4), N stage (0 vs. others), histological grade (well vs. moderately or poorly differentiated), surgical margins (negative vs. close or positive), and number of pathologically metastatic lymph nodes (0 or 1 vs. ≥2).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and Ekuseru-Toukei 2012 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used for the statistical analyses. The association of each variable with the NLR, LMR and PLR were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test for ordinal variables and the Fisher’s exact test or the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. Cumulative DSS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier product limit method. Significance among the curves was determined using the log-rank test. Probabilities of less than 0.05 were accepted as significant. All of the variables associated with the DSS or OS were introduced into multivariate Cox proportional hazard models. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated.

Results

The mean follow-up time among the 433 patients was 59.1 (range, 1–179) months. During the follow-up period, the 5-year OS rate and DSS were 77.3 and 84.1%. The tongue was the most common site [n = 211 (48.7%)].

The mean NLR, LMR, and PLR were 2.50 ± 1.73, 5.51 ± 3.47, and 143.4 ± 71.7, respectively. The optimal cutoff values of NLR, LMR, and PLR were 2.22, 4.35, and 134.3, respectively. The AUC of the NLR ROC curve was 0.72 (sensitivity, 0.71; specificity, 0.58). The AUC of the LMR ROC curve was 0.66 (sensitivity, 0.62; specificity, 0.62). The AUC of the PLR ROC curve was 0.60 (sensitivity, 0.56; specificity, 0.59).

There were significant differences between the two NLR groups in the presence of pathological multiple lymph node metastases (P = 0.044) in the univariate analysis (Table 1). There were no significant differences in other factors (Table 1). There were significant differences between the patients with high PS (P = 0.002), subsite other than the tongue (P = 0.015), high T stage (P = 0.003), and high N stage (P = 0.007) in the patients with low LMR in the univariate analysis (Table 2). There were no significant differences in other factors (Table 2). There were significant differences between the females (P < 0.001) and no smoking history (P = 0.002) in the high PLR group in the univariate analysis (Table 3). There were no significant differences in other factors (Table 3).

Univariate analysis showed that high T stage (P < 0.001), high N stage (P < 0.001), high NLR (P < 0.001), low LMR (P < 0.001), high PLR (P = 0.044), ENE (P = 0.004), pathological multiple lymph node metastases (P < 0.001), involved margins (P = 0.030), and moderately or poorly differentiated histology (P < 0.001) were associated with poor 5-year DSS (Table 4). Univariate analysis showed that high PS (P = 0.025), high T stage (P < 0.001), high N stage (P < 0.001), high NLR (P < 0.001), low LMR (P = 0.001), ENE (P = 0.012), pathological multiple lymph node metastases (P < 0.001), involved margins (P = 0.043), and moderately or poorly differentiated histology (P = 0.001) were associated with poor 5-year OS (Table 4).

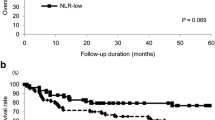

The 5-year DSS rates of patients with high and low NLR were 75.5 and 91.4%, respectively (Fig. 1). The 5-year OS rates of patients with high and low NLR were 68.8 and 84.6%, respectively. The 5-year DSS rates of patients with high and low LMR were 89.1 and 76.3%, respectively (Fig. 2). The 5-year OS rates of patients with high and low LMR were 82.1 and 70.0%, respectively. The 5-year DSS rates of patients with high and low PLR were 80.6 and 86.6%, respectively (Fig. 3). The 5-year OS rates of patients with high and low PLR were 75.6 and 78.4%, respectively.

In multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis, high NLR (Hazard ratio, HR 2.87; 95% confidence interval, CI 1.59–5.19; P < 0.001), moderately or poorly differentiated histology (HR 2.37, 95% CI 1.32–4.25, P < 0.001), and ENE (HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.13–3.35, P = 0.016) were independent predictors of DSS (Table 5). Also, high NLR (HR 2.30, 95% CI 1.42–3.72, P < 0.001), moderately or poorly differentiated (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.07–2.76, P = 0.025), and ENE (HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.13–2.84, P = 0.013) were independent predictors of OS (Table 6).

Discussion

We successfully investigated the prognostic values of NLR, LMR, and PLR in patient survival and their associations with the clinicopathologic characteristics of Japanese OSCC patients. In particular, high NLR was associated with poor prognosis.

The association between NLR and prognostic factors have been reported in various cancers [6, 16]. The measurement of NLR is very accessible and affordable because blood sampling is used. Therefore, NLR could be used as a simple indicator of systemic inflammatory responses in cancer patients. Neutrophils secrete matrix metalloproteinase 9 to promote carcinogenesis and tumor cell proliferation into the cancer microenvironment [17, 18]. In contrast, lymphocytes suppress tumor progression and are associated with an increased survival in various cancers [19, 20]. In this study, like other reports, a high NLR was associated with poor DSS and OS [15, 21, 22]. In multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis, high NLR (HR 2.87) was an independent predictor of poor prognosis. The cutoff value of NLR ranged from 1.77 to 5 [23]. In Japan, Nakashima et al. and Sano et al. reported that the cutoff values were 2.4 and 2.36, respectively [15, 24]. In this study, the cutoff value was 2.22, like in these reports. The association between NLR and clinicopathological factors such as lymph node metastasis, T stage, differentiation, and perineural invasion was reported [23]. In this study, there were significant differences in the presence of pathological multiple lymph node metastases in the patients with high NLR like in several reports [14, 21, 22]. Therefore, NLR may be useful in predicting multiple lymph node metastasis.

The association between LMR and prognostic factors were reported in head and neck cancers [12]. Ong et al. reported that low pretreatment LMR indicated poor survival in patients with early tongue cancer [24]. In this study, low LMR was associated with poor DSS and OS like their report. A low LMR may mean a relative decrease in lymphocytes and increase in monocytes. The decreasing lymphocytes may be related to high NLR or high PLR. Tsai et al. reported that a higher pretreatment count of circulating monocytes was independently associated with poor prognosis in patients with oral cancer [25]. Chronic inflammation including cancer increases the monocyte count by the secretion of various cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 [26]. Generally, the monocytes differentiate into macrophages. Pollard et al. reported that an increased number of tumor-associated macrophages was associated with poor prognosis in cancers [27]. The cutoff value of LMR ranged from 2.35 to 5.22 [12, 24]. In this study, the cutoff value was 4.35 like these reports.

The relationship between PLR and poor prognosis is controversial. Several investigators suggested that a high PLR indicated poor prognosis in patients with head and neck SCC [13, 24]. In this study, a high PLR was associated with poor DSS. In contrast, Yu et al. indicated that preoperative PLR was not associated with survival or relapse in oral, pharyngeal, and lip cancer [28]. There are several possibilities, although the exact mechanism of the association between a high PLR and poor prognosis is not clear. Platelets can promote tumor progression by increasing angiogenesis through secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor, and invasion, and metastasis through epithelial-mesenchymal transition [13, 29,30,31,32]. The cutoff value of PLR ranged from 82 to 150 [13]. In patients with oral cancer, Chen et al. and Ong et al. reported that the cutoff values were 135 and 129 [24, 33]. In this study, the cutoff value was 134 like those reports. In multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis of this study, a low LMR and high PLR were not independent predictors of poor prognosis. Therefore, unlike NLR and other factors, LMR and PLR may not be useful in Japanese OSCC patients.

This study had several limitations. First, this study was conducted in Japanese OSCC patients. Each cutoff value was different from other studies. Therefore, it may be clinically difficult to be used in patients of other countries. Second, the present study was retrospective and nonrandomized. Therefore, bias could not be completely excluded, although multivariate analysis was performed to decrease the effect of confounding factors as much as possible. Future research should involve a large-scale prospective cohort study to evaluate predictors of prognosis and NLR, LMR, or PLR.

Conclusions

High NLR, moderately or poorly differentiated histology, and ENE were independent predictors of DSS and OS. In particular, high NLR was associated with poor prognosis. The NLR might be a potential independent prognostic factor in Japanese OSCC patients.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- DSS:

-

Disease-specific survival

- LMR:

-

Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- OSCC:

-

Oral squamous cell carcinoma

- PLR:

-

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

References

Lingen MW, Kalmar JR, Karrison T, Speight PM. Critical evaluation of diagnostic aids for the detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(1):10–22.

Rivera C, Oliveira AK, Costa RAP, De Rossi T, Paes Leme AF. Prognostic biomarkers in oral squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2017;72:38–47.

Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–7.

Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Cell. Immun Inflammation Cancer. 2010;140(6):883–99.

Templeton AJ, Ace O, McNamara MG, Al-Mubarak M, Vera-Badillo FE, Hermanns T, Seruga B, Ocaña A, Tannock IF, Amir E. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23(7):1204–12.

Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocaña A, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju124.

Wang Y, Huang D, Xu WY, Wang YW, Che GW. Prognostic value of pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncol Res Treat. 2019;42(10):523–31.

Torisu H, Ono M, Kiryu H, Furue M, Ohmoto Y, Nakayama J, et al. Macrophage infiltration correlates with tumor stage and angiogenesis in human malignant melanoma: possible involvement of TNF-alpha and IL-1alpha. Int J Cancer. 2000;85(2):182–8.

Varney ML, Olsen KJ, Mosley RL, Singh RK. Paracrine regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor--a expression during macrophage-melanoma cell interaction: role of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Interf Cytokine Res. 2005;25(11):674–83.

Trellakis S, Farjah H, Bruderek K, Dumitru CA, Hoffmann TK, Lang S, Brandau S. Peripheral blood neutrophil granulocytes from patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma functionally differ from their counterparts in healthy donors. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24(3):683–93.

Mascarella MA, Mannard E, Silva SD, Zeitouni A. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in head and neck cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40(5):1091–100.

Tham T, Olson C, Khaymovich J, Herman SW, Costantino PD. The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator in head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275(7):1663–70.

Takenaka Y, Oya R, Kitamiura T, Ashida N, Shimizu K, Takemura K, Yamamoto Y, Uno A. Platelet count and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as prognostic markers for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40(12):2714–23.

Nakashima H, Matsuoka Y, Yoshida R, Nagata M, Hirosue A, Kawahara K, et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts the chemoradiotherapy outcome and survival in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:41.

Sano Y, Kogashiwa Y, Araki R, Enoki Y, Ikeda T, Yoda T, Nakahira M, Sugasawa M. Correlation of inflammatory markers, survival, and COX2 expression in oral cancer and implications for prognosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(4):667–76.

Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88(1):218–30.

Ardi VC, Kupriyanova TA, Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Human neutrophils uniquely release TIMP-free MMP-9 to provide a potent catalytic stimulator of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(51):20262–7.

Liang W, Ferrara N. The complex role of neutrophils in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(2):83–91.

Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):298–306.

Rusakiewicz S, Semeraro M, Sarabi M, Desbois M, Locher C, Mendez R, et al. Immune infiltrates are prognostic factors in localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res. 2013;73(12):3499–510.

Wu CN, Chuang HC, Lin YT, Fang FM, Li SH, Chien CY. Prognosis of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in clinical early-stage tongue (cT1/T2N0) cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:3917–24.

Kao HK, Löfstrand J, Loh CY, Lao WW, Yi JS, Chang YL, Chang KP. Nomogram based on albumin and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for predicting the prognosis of patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13081.

Yang Y, Liu R, Ren F, Guo R, Zhang P. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with oral cancer. Biosci Rep. 2018;38(6). pii: BSR20181550.

Ong HS, Gokavarapu S, Wang LZ, Tian Z, Zhang CP. Low pretreatment lymphocyte-monocyte ratio and high platelet-lymphocyte ratio indicate poor cancer outcome in early tongue cancer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(8):1762–74.

Tsai YD, Wang CP, Chen CY, Lin LW, Hwang TZ, Lu LF, Hsu HF, Chung FM, Lee YJ, Houng JY. Pretreatment circulating monocyte count associated with poor prognosis in patients with oral cavity cancer. Head Neck. 2014;36(7):947–53.

Sajadieh A, Mouridsen MR, Selmer C, Intzilakis T, Nielsen OW, Haugaard SB. Monocyte number associated with incident cancer and mortality in middle-aged and elderly community-dwelling Danes. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(13):2015–22.

Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(1):71–8.

Yu W, Dou Y, Wang K, Liu Y, Sun J, Gao H, Liu S, Wei F, Yuan D, Song X, Qu X. Preoperative neutrophil lymphocyte ratio but not platelet lymphocyte ratio predicts survival and early relapse in patients with oral, pharyngeal, and lip cancer. Head Neck. 2019;41(5):1468–74.

Sabrkhany S, Griffioen AW, Oude Egbrink MG. The role of blood platelets in tumor angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1815(2):189–96.

Jain S, Harris J, Ware J. Platelets: linking hemostasis and cancer. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(12):2362–7.

J Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):576–90.

Sierko E, Wojtukiewicz MZ. Platelets and angiogenesis in malignancy. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2004;30(1):95–108.

Chen S, Guo J, Feng C, Ke Z, Chen L, Pan Y. The preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio versus neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: which is better as a prognostic factor in oral squamous cell carcinoma? Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016;8(3):160–7.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage (https://www.editage.jp/) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TH: substantial contributions to the conception, design of the work, interpretation of data, drafted the work, approved the submitted version. TI: the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, approved the submitted version. DT: the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, substantively revised draft, approved the submitted version. RA: the acquisition, analysis, substantively revised draft, approved the submitted version. IS: the acquisition, analysis, substantively revised draft, approved the submitted version. YK: the acquisition, analysis, substantively revised draft, approved the submitted version. JK: substantial contributions to the conception, substantively revised draft, approved the submitted version. AK: substantial contributions to the conception, substantively revised draft, approved the submitted version. AS: substantial contributions to the conception, substantively revised draft, approved the submitted version. MA: substantial contributions to the conception, design of the work, substantively revised draft, approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine and by the institutional review boards of the participating hospitals. Informed consent from participants was waived, as this is a retrospective study. Instead, we published the information regarding this study and granted occasions of refusing to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hasegawa, T., Iga, T., Takeda, D. et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio associated with poor prognosis in oral cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer 20, 568 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07063-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07063-1