Abstract

Background

Liver function is routinely assessed in clinical practice as liver function tests provide sensitive indicators of hepatocellular injury. However, the prognostic value of enzymes that indicate hepatic injury has never been systematically investigated in lymphoma, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Methods

This study examined the prognostic value of baseline aspartic transaminase (AST) in DLBCL patients. The association between AST and clinical features was analyzed in 179 DLBCL patients treated from 2006 to 2016. All enrolled patients were treated with R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like chemotherapy. Log-rank test, univariable analysis, and subgroup analysis were performed to evaluate the impact of AST on survival.

Results

AST 33.3 U/L was considered to be the optimal threshold value for predicting prognosis. A higher AST level was associated with advanced stage (P = 0.001), poorer performance status (P = 0.014), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (P < 0.0001), presence of B symptoms (P = 0.001), high-risk International Prognostic Index (IPI, IPI 3–5) (P = 0.002), non-germinal center B-cell subtypes (P = 0.038), hepatitis B virus surface antigen positivity (P = 0.045) and more extra nodal involvement (ENI, ENI ≥ 2) (P = 0.027). Patients with a higher AST level had a shorter overall survival (OS) (2-year OS rate, 53.6% vs. 83.6%, P < 0.001). Subgroup analysis indicated that higher AST levels have poorer prognostic values in patients without B symptoms and LDH positive groups.

Conclusion

A pretreatment AST level is associated with OS in DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP or similar chemotherapy regimens. A high pretreatment AST level might be a reliable prognostic factor for predicting a dismal outcome in DLBCL patients. Serum AST levels may be investigated for use as an easily determinable, inexpensive biomarker for risk assessment in patients with DLBCL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is one of the most common forms of malignant lymphoma, accounting for 30–40% of all newly diagnosed cases of adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). DLBCL is a heterogeneous disease, in terms of morphology, clinical features, biological behavior, and response to therapies [1], which makes predicting patient prognosis challenging. The International Prognostic Index (IPI) and the gene expression profile classification are the most widely accepted prognostic scoring systems. However, there are still patients with a favorable IPI who suffer from disease recurrence [2, 3], and gene expression profiling is not yet a practical prognostic tool in routine practice.

Molecular markers and immunohistochemical profiling are other prognostic strategies in DLBCL currently in use, but these methods are sometimes costly and always rely on tissue samples. Therefore, alternative readily available prognostic biomarkers with low clinical costs are urgently needed to improve risk assessment in DLBCL patients.

Liver function is routinely assessed in clinical practice as liver function tests provide sensitive indicators of hepatocellular injury. Importantly, it has been reported that high aspartate aminotransaminase (AST) levels in breast cancer patients are not always associated with significant liver disease but they do correlate with an advanced clinical stage of breast cancer [4]. Furthermore, a higher preoperative AST/alanine aminotransaminase (ALT) ratio predicts poor outcome in patients with upper tract urothelial cancer [5]. Similarly, high serum AST levels before surgery may serve as a valuable prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [6]. Thus, we analyzed the clinical significance and the prognostic value of these two enzymes that indicate hepatic injury, ALT or glutamic-pyruvic transaminase and AST or glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, in patients with de novo DLBCL.

Methods

Patient selection

We reviewed medical records of 207 patients who were diagnosed, according to the 2016 World Health Organization classification, with de novo DLBCL at the Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University and Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University between 2006 and 2016. Blood samples of all patients were collected at the time of diagnosis or before the beginning of treatment. No patients with relapse after treatment were included in this study. Likewise, patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, transformed NHL, and HIV-positive DLBCL were excluded from the study. Further cases also excluded from the study, including patients with a history of hepatitis (9/207, 4.3%), chronic alcohol ingestion (5/207, 2.4%), cirrhosis, recent medication for hepatotoxicity (2/207, 1.0%), and fatty liver (2/207, 1.0%), patients with pretreatment liver function injury due to viral infection (10/207, 4.8%), and patients with concomitant or past liver cancer (none). Consequently, 179 patients with DLBCL qualified for the study. All enrolled patients were treated with R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) or R-CHOP-like chemotherapy. Because this is a retrospective study, all recruited patients were informed and verbal consent was obtained in accordance with the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research project was approved by the review boards of Jiangnan University, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan and Nantong Universities.

Optimal cutoff value by X-tile software

X-tile 3.6.1 software (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) was used to determine the optimal cut-off values for ALT and AST. However, the optimal cutoff value for ALT was not found. Thus, we used 50 U/L for ALT according to the reference value in a liver function test. The optimal cutoff value was 33.3 U/L for AST according to the X-tile software recommendation. Results provided by the X-tile software showed that a dichotomy in the AST level had a better prognostic value than a trichotomy (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Differential gene expression using the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database data

The DLBCL microarray and corresponding clinical data in the present study were downloaded from the public GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the accession number GSE27255. Raw data from the GEO database were extracted using the R Bioconductor limma and impute packages (http://bioconductor.org/biocLite.R). The data were presented as Volcano and Heatmap plots. The selected mRNAs were examined in cell lines of germinal center B-cell (GCB) and activated B-cell (ABC) subtype to explore if any significant differences in expression exist. Using Mann-Whitney U test, results of fold change > 1 and P < 0.05 between GCB and ABC cell lines were considered significant.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-μm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections. The antibodies used in the study were for CD20 (clone L26, Abcam, cutoff: 30%), CD10 (clone 56C6, Dako, cutoff: 30%), Bcl6 (clone LN22, Dako, cutoff: 30%), MUM1 (clone MUM1p, Dako, cutoff: 30%), and Myc (clone Y69; Abcam, cutoff: 40%). The cutoff values for each antibody have been previously described [7].

Statistical analysis

Univariable tests were used to compare categorical (Chi-square and Fisher’s exact) and continuous (Student’s t test or Kruskal-Wallis test when appropriated) variables. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared using log-rank test. According to Cheson 2014, overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to death; patients who remained alive were censored at the last date of follow-up [8]. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, Version 20.0. For all the tests, P < 0.05 (2-sided) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

The median age of the cohort was 57 years (range 18–88 years old). The median follow up time was 28 months (3–112 months). The median treatment cycle was 6 cycles (4–8 cycles). The frequencies with elevated ALT and AST levels were 12.3% (22/179) and 24.6% (44/179), respectively. The baseline clinical parameters of the patients are presented in Table 1.

mRNA levels of ALT and AST in patients with lymphoma in GEO

DLBCL patients with different cells of origin (COO) have distinct outcomes; therefore, we analyzed the differently expressed genes in the GCB and ABC subtypes. We speculated that higher ALT or AST mRNA levels were more frequent in the ABC subgroup. Thus, the Human DLBCL of the Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array microarray data were downloaded from the public GEO database. Differently expressed genes in the DLBCL cell lines of the GCB and ABC subtypes (Table 2) were analyzed. A total of 25 genes were differentially expressed as shown in the Volcano and Heatmap plots (Figs. 1 and 2). However, the expression of ALT and AST mRNA was similar between the GCB and ABC cell lines. These results suggest that the mRNA levels of ALT or AST may not be reliant on the COO.

Heatmap plot of different expressed genes with GEO data in human DLBCL cell lines. Heat map hierarchical clustering reveals 25 genes were differentially expressed between GCB and ABC DLBCL cell lines. Neither ALT nor AST was among the different expressed genes. Abbreviations: ALT: alanine aminotransaminase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; GEO: gene expression omnibus

Association between clinical features and ALT or AST level

In the present cohort, ALT-positive and ALT-negative patients had similar clinical features. However, AST positivity was significantly associated with advanced Ann Arbor stage (stage III or IV) (P = 0.001), poor performance status (PS) (P = 0.014), elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (P < 0.0001), more extra nodal involvement (ENI, ENI ≥ 2) (P = 0.027), high-risk IPI (IPI 3–5) (P = 0.002), presence of B symptoms (P = 0.001), hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity (P = 0.045) (Fig. 3a), Myc protein positivity (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3b), and non-GCB subtypes (P = 0.038) (Table 3).

Survival analysis associated with ALT and AST levels

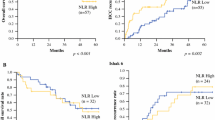

To extend our findings, survival analysis was performed in our cohort. ALT-positive patients showed similar OS to the negative cases (Fig. 4a). However, AST-positive cases, showed significantly decreased OS compared with the negative ones (2-year OS, 49.2% vs. 81.1%, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4b). Other clinical and pathological factors were also associated with poor survival, including B symptoms, non-GCB subtype, advanced Ann Arbor stage, poor PS, elevated LDH level, ENI ≥ 2, and high-risk IPI (Fig. 4c-h). In subgroup analysis, patients with higher AST levels showed poorer outcomes in patients without B symptoms ((Fig. 5a) and LDH positive groups (Fig. 6c). Higher AST levels showed poorer survival in patients of different ENI (both ENI < 2 and ENI ≥ 2 groups) (Fig. 5c-d), COO (both GCB and non-GCB groups) (Fig. 5e-f) and IPI risk showed (both IPI 0–2 and IPI 3–5 groups) (Fig. 6a, b). Patients of different AST level had similar OS with either Myc protein positive or negative group (Fig. 6e-f).

The differences of overall survival in cases grouped according to ALT (a), AST (b), A or B symptom (c), histological type (d), PS status (e), LDH level (f), extranodal involvement (g) and IPI risk stratification (h). Abbreviations: ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ECOG PS: performance status of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ENI: extra nodal involvement; GCB: germinal-center B-cell type; IPI: International Prognostic Index; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; OS: overall survival

Subgoup analysis with different clinicopathological factors. Patients of higher AST level had superior prognostic value in “A symptoms” group (a). Patients of higher AST level showed poorer outcome regardless of ENI status (c-d) and COO (e-f). Abbreviations: AST: aspartate aminotransferase; COO: cells of origin; ENI: extra nodal involvement; GCB: germinal-center B-cell type; OS: overall survival

Subgoup analysis with different clinicopathological factors. Patients of higher AST level had superior prognostic value in LDH positive group (c). Patients of higher AST level showed poorer outcome regardless of IPI risk (a-b). Patients of higher AST had similar OS in different Myc protein status (e-f). Abbreviations: AST: aspartate aminotransferase; IPI: International Prognostic Index; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; OS: overall survival

Discussion

It has been reported that a Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection can cause long term necro-inflammatory liver damage, resulting in lower deactivation of estrogen, which is a dominant risk factor for breast cancer [9]. Furthermore, HBV infection has been associated with a greater risk of developing NHL, especially DLBCL, follicular lymphoma, and T cell lymphoma [1]. In addition, HBsAg-positive DLBCL patients have been shown to usually have significantly worse outcomes than HBsAg-negative patients [3]. However, a recent study has indicated that liver impairment and not the viral hepatitis status affects the outcome of DLBCL patients [10]. In the present study, we evaluated the prognostic value of two hepatic enzymes (ALT and AST), routinely assessed in liver function tests, in DLBCL patients who had no evidence of prior HBV infection. The AST level, obtained as a part of a pretreatment liver function test, is a novel prognostic factor in DLBCL patients. This is the first time that the prognostic value of the serum AST level in DLBCL patients has been discussed in published literature. We provide evidence that a higher pretreatment AST level is associated with poorer OS. Furthermore, a higher AST level at diagnosis is significantly related to high-risk clinical features in patients who received R-CHOP or similar chemotherapy regimens. Higher AST level had superior prognostic values in patients of “A symptoms” and LDH positive groups by subgroup analysis.

Levels of ALT and AST are particularly high in the liver. In China, like in many other countries, ALT and AST are usually tested in the same panel [11]. Hypoxia, trauma, ischemia, damage of cell membrane integrity, and function impairment can cause increased cell permeability, mitochondrial swelling, and cell rupture, which in turn cause ALT and AST to be released into the bloodstream. Consequently, the serum AST and ALT levels are closely related to the severity of liver injury [6, 12]. Furthermore, AST is also present in hepatocyte mitochondria and plays a significant role in numerous tissues [11].

Beside normal cells, malignant cells can also generate AST and it has been increasingly recognized that AST plays an important role in carcinogenesis [4, 6, 13, 14]. Studies have demonstrated that a higher AST level is significantly associated with an unfavorable prognosis in numerous cancers, such as hepatocellular and renal cell carcinoma as well as colonic, pancreatic, NSCLC, and breast cancer [6, 15,16,17,18]. However, the prognostic value of serum AST levels in patients with malignant lymphoma, especially DLBCL, is still unknown.

This study demonstrates that a high AST level is associated with high-risk clinical features. We must acknowledge that a high AST level was more common in the non-GCB subtype in our study; however, the expression of AST was similar between the GCB and ABC cell lines. This difference might be explained by different sorting techniques and sample sources. The survival analysis presented in this study showed a high AST level predicted a decreased OS in DLBCL patients. However, the prognostic value of AST levels in literature is controversial. Similarly to our study, Kiba et al. have shown that the prognosis of patients with multiple myeloma with a high AST level is worse than the prognosis of patients with a low AST level. [14]. Further research has also suggested that blood-based serum AST is a useful outcome prediction tool in hepatocellular carcinoma [19]. However, Chen and his colleagues have shown that elevated AST levels are significantly associated with longer relapse free survival and OS in NSCLC patients [6].

The underlying relationship between AST and cancer activity is unclear. Glycolysis, which produces ATP and anabolic precursors, is necessary for cancer cells to survive, grow, and invade [20,21,22]. Some studies have shown that malignant proliferating cells can also obtain energy through glutamine metabolism which is catalyzed by AST [20, 21, 23]. In vitro, oxamate, which targets AST, can inhibit the proliferation of transformed breast adenocarcinoma cells [17]. Thus, high AST levels might in turn promote cell proliferation. In addition, mice with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver damage with a high AST level treated with chemotherapy exhibit decreased MYC levels, which can significantly decrease the level of AST and suggest liver function recovery [24]. In our study, we also show that a higher AST level in DLBCL patients was frequently accompanied by higher Myc protein expression. Therefore, we suggest that MYC and AST have a synergetic effect in tumorigenesis, which could indirectly indicate that a higher level of AST is a predictor of poor outcome in DLBCL patients.

Witjes et al. have shown a high AST level and viral load are two independent factors associated with poor survival in HCC and that a high AST level in HCC patients is also associated with a higher HBV DNA [19]. Studies have also confirmed a strong association between HBV infection and DLBCL occurrence [25]. In China, about 13.8% of DLBCL cases are HBV-positive and show unique advanced clinical features [26]. HBV carriers show significantly increased levels of AST. In our study, we noticed a high HBsAg level was associated with an elevated AST level, which indicated dismal outcomes. However, none of these patients with high HBsAg levels had increased HBV DNA copy numbers, which indicated that the raised AST levels were more likely to be caused by lymphoma activity and not by HBV replication. Together, our findings suggest that high AST levels in de novo DLBCL patients are associated with unfavorable prognosis when treated with normal first-line chemotherapy. Thus, more intensive first-line regimens might improve the outcome of these patients.

Conclusions

This study is limited due to its retrospective and small-scale design; further prospective studies with more patients are required. Nonetheless, our study indicates that a pretreatment AST level is associated with many unfavorable clinical characteristics and is an unfavorable prognostic factor for OS in DLBCL patients treated with normal first-line chemotherapy regimens. We suggest more intensive therapies might overcome the unfavorable outcome of these patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

Activated B-cell type

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- COO:

-

Cells of origin

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- ECOG PS:

-

Performance status of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- ENI:

-

Extra nodal involvement

- GCB:

-

Germinal center B-cell type

- GEO:

-

Gene expression omnibus

- HBsAg:

-

HBV surface antigen

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- IPI:

-

International Prognostic Index

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- R-CHOP:

-

Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone

References

Dalia S, Chavez J, Castillo JJ, Sokol L. Hepatitis B infection increases the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Leuk Res. 2013;37(9):1107–15.

Merli M, Visco C, Spina M, Luminari S, Ferretti VV, Gotti M, Rattotti S, Fiaccadori V, Rusconi C, Targhetta C, et al. Outcome prediction of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas associated with hepatitis C virus infection: a study on behalf of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Haematologica. 2014;99(3):489–96.

Wang F, Xu RH, Luo HY, Zhang DS, Jiang WQ, Huang HQ, Sun XF, Xia ZJ, Guan ZZ. Clinical and prognostic analysis of hepatitis B virus infection in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:115–25.

Birtle A, Lawton P, Chaundary M, Richman P, McFarlane B. Unexplained high AST in locally advanced breast cancer. Breast J. 2003;9(6):505–6.

Lee H, Choi YH, Sung HH, Han DH, Jeon HG, Chang Jeong B, Seo SI, Jeon SS, Lee HM, Choi HY. De Ritis ratio (AST/ALT) as a significant prognostic factor in patients with upper tract urothelial Cancer treated with surgery. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(3):e379–85.

Chen SL, Xue N, Wu MT, Chen H, He X, Li JP, Liu WL, Dai SQ. Influence of preoperative serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level on the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(9):1–12.

Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Campo E, Braziel RM, Jaffe ES, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103(1):275–82.

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Lister TA, Alliance AL, Lymphoma G. Eastern cooperative oncology G, European mantle cell Lymphoma C et al: recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–68.

Adhikari VP, Lu LJ, Kong LQ. Does hepatitis B virus infection cause breast cancer? Chin Clin Oncol. 2016;5(6):81.

Dlouhy I, Torrente MA, Lens S, Rovira J, Magnano L, Gine E, Delgado J, Balague O, Martinez A, Campo E, et al. Clinico-biological characteristics and outcome of hepatitis C virus-positive patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(3):405–10.

Xu Q, Higgins T, Cembrowski GS. Limiting the testing of AST: a diagnostically nonspecific enzyme. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144(3):423–6.

van Beek JH, de Moor MH, de Geus EJ, Lubke GH, Vink JM, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI. The genetic architecture of liver enzyme levels: GGT, ALT and AST. Behav Genet. 2013;43(4):329–39.

Chen SL, Li JP, Li LF, Zeng T, He X. Elevated preoperative serum alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase (ALT/AST) ratio is associated with better prognosis in patients undergoing curative treatment for gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6):1–11.

Kiba T, Ito T, Nakashima T, Okikawa Y, Kido M, Kimura A, Kameda K, Miyamae F, Tanaka S, Atsumi M, et al. Bortezomib and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma: higher AST and LDH levels associated with a worse prognosis on overall survival. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:462–71.

Bezan A, Mrsic E, Krieger D, Stojakovic T, Pummer K, Zigeuner R, Hutterer GC, Pichler M. The preoperative AST/ALT (De Ritis) ratio represents a poor prognostic factor in a cohort of patients with nonmetastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2015;194(1):30–5.

Shen SL, Fu SJ, Chen B, Kuang M, Li SQ, Hua YP, Liang LJ, Guo P, Hao Y, Peng BG. Preoperative aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio is an independent prognostic factor for hepatitis B-induced hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(12):3802–9.

Thornburg JM, Nelson KK, Clem BF, Lane AN, Arumugam S, Simmons A, Eaton JW, Telang S, Chesney J. Targeting aspartate aminotransferase in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(5):84–95.

Stocken DD, Hassan AB, Altman DG, Billingham LJ, Bramhall SR, Johnson PJ, Freemantle N. Modelling prognostic factors in advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(6):883–93.

Witjes CD, JN IJ, van der Eijk AA, Hansen BE, Verhoef C, de Man RA. Quantitative HBV DNA and AST are strong predictors for survival after HCC detection in chronic HBV patients. Neth J Med. 2011;69(11):508–13.

Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(2):85–95.

Hsu PP, Sabatini DM. Cancer cell metabolism: Warburg and beyond. Cell. 2008;134(5):703–7.

DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, Thompson CB. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19345–50.

Elf SE, Chen J. Targeting glucose metabolism in patients with cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(6):774–80.

Zhao X, Chen Q, Li Y, Tang H, Liu W, Yang X. Doxorubicin and curcumin co-delivery by lipid nanoparticles for enhanced treatment of diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;93:27–36.

Tajima K, Takahashi N, Ishizawa K, Murai K, Akagi T, Noji H, Sasaki O, Wano M, Itoh J, Kato Y, et al. High prevalence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in occult hepatitis B virus-infected patients in the Tohoku district in eastern Japan. J Med Virol. 2016;88(12):2206–10.

Deng L, Song Y, Young KH, Hu S, Ding N, Song W, Li X, Shi Y, Huang H, Liu W, et al. Hepatitis B virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: unique clinical features, poor outcome, and hepatitis B surface antigen-driven origin. Oncotarget. 2015;6(28):25061–73.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The design, collection, analysis of the study, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript were supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81600152), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20160194), and Jiangsu Province Young Medical Talents (QNRC2016155).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TXL and XHW were responsible for conception and design. TXL, SW, DYC, TTH, YZ, HQG and HYH contributed to collection and assembly of data, TXL and SW performed the experiments. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by TXL, SW, DYC, TTH, YZ, HQG, HYH and XHW, TXL and SW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and provided final approval of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Because this is a retrospective study, all recruited patients were informed and verbal consent was obtained in accordance with the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the research project was approved by the review boards of Jiangnan University, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan and Nantong Universities.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Dichotomy of AST level showed a high prognosis value according to X-tile. The optimal cutoff value was 33.3 U/L for AST. (TIF 1208 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S2. Trichotomy of AST level showed a low prognosis value according to X-tile. No optimal cutoff value was observed. (TIF 1213 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, TX., Wu, S., Cai, DY. et al. Prognostic significance of serum aspartic transaminase in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer 19, 553 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5758-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5758-2