Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine the HPV positivity rate in patients with laryngeal cancer, and to determine the effect of HPV positivity on survival. An additional aim was to determine if patients with HPV positive laryngeal cancer are more sensitive to chemotherapy and if such sensitivity differs according to chemotherapy protocol.

Methods

The study included laryngeal specimens obtained from 82 laryngeal cancer patients and 11 laryngeal specimens with normal laryngeal mucosa that were obtained from our hospital’s paraffin block archives between 1995 and 2013. HPV was detected via chromogenic in situ hybridization (cISH) and confirmed via genotyping.

Results

HPV was not detected in any of the 82 laryngeal cancer patients’ laryngeal specimens, nor in any of the 11 archived laryngeal specimens with normal laryngeal mucosa via cISH. Genotyping confirmed these findings; none of the HPV types studied were detected in any of the specimens. As none of the study samples were HPV positive, it was not possible to compare survival, recurrence, or chemotherapy sensitivity.

Conclusions

HPV infection is not a leading cause of laryngeal cancer; however, additional research on HPV positivity in patients with laryngeal cancer and its effect on recurrence, survival, and chemotherapy sensitivity is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Laryngeal cancer is the 20th most common cancer in Europe, with around 39,900 new cases diagnosed in 2012 (1% of the total) [1]. Laryngeal cancer is known to be caused primarily by tobacco and alcohol consumption; however, viral infections including human papillomavirus (HPV) have also been associated with head and neck cancer [2,3,4,5,6]. Laryngeal cancer differs from the other head and neck cancers in that several studies on HPV positive and HPV negative laryngeal cancer patients reported no difference in chemotherapy sensitivity and survival [7,8,9].

Although the reported incidence of HPV positivity in laryngeal cancer patients varies [9,10,11,12] fewer data are available for laryngeal cancer, as compared to oropharyngeal cancer, in terms of HPV infection, survival, and chemotherapy sensitivity. Moreover, there is a lack of data on the frequency of HPV positivity in patients with laryngeal cancer in Turkey. The aim of the present study was to determine the HPV positivity rate in patients with laryngeal cancer, and to determine the effect of HPV positivity on survival. An additional aim was to determine if patients with HPV positive laryngeal cancer are more sensitive to chemotherapy and if such sensitivity differs according to chemotherapy protocol.

Methods

Patient demographics

Retrospective data analysis was performed to include patients with laryngeal cancer between 1995 and 2013. The patients who had laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, who had a biopsy spesimen available in the Pathology Paraffin Block Archives, who received chemoradiotherapy as the first line treatment were included. All patients underwent chemoradiotherapy post diagnosis, and all chemotherapy protocols included an alkylating agent. Patients that received any treatment before direct laryngoscopy and biopsy, had surgery as the primary treatment procedure, received only radiotherapy, and those with follow-up < 2 years were excluded. 82 patients met the criteria and the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens (FFPE) and slides of tumors stained with H&E for each patient were retrieved. All patient slides were re-examined for confirmation of the diagnosis.

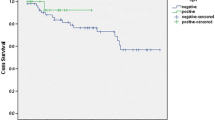

The retrospective data analysis included demographic and clinical findings, as well as the histopathological characteristics of the tumor. Grade of differentiation, primary tumor extension, and nodal status, were recorded. Treatment regimens and the recurrence status were also assessed. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from the date chemoradiotherapy was initiated to the time recurrence was detected.

The control group comprised of 11 laryngeal specimens reported as normal laryngeal mucosa obtained from the Department of Pathology Paraffin Block Archives. These pathological specimens included 6 male and 5 female patients. The mean age of these subjects was 47.45 years, ranging from 35 to 62 years. These 11 patients had undergone endoscopic laryngeal surgery for benign lesions. These lesions were resected and biopsied during the direct laryngoscopy procedure. These biopsy specimens were reported to be normal laryngeal mucosa without evidence of a premalignant or a malignant lesion.

HPV was detected via chromogenic in situ hybridization (cISH) and was confirmed via genotyping. The study was approved by the University Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

HPV DNA detection via in situ hybridization (ISH), HPV DNA detection and typing

High-risk (HR)-HPV DNA in-situ hybridization (ISH) was done using proprietary reagents (Inform HPV III Family 16 Probe [B], Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., USA), which can detect high risk HPV genotypes (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58 and 66) [13]. HR-HPV(+) cervical specimens were used as the positive control group and HR-HPV(−) cervical specimens were used as the negative control group. The HR-HPV ISH test was scored as positive if there was any blue reaction product that co-localized with cell nuclei [13]. The staining was reported as positive if it showed diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining or punctate nuclear staining. Staining that was pale and limited to the nucleoli of cells were reported as negative.

Flow-through hybridization was performed for HPV genotyping, using an HBGA-21 GenoArray Diagnostic Kit (HybriBio Biotechnology Ltd. Corp., Chaozhou, Guangdong Province, China) in accordance to the manufacturer’s instructions. The HPV GenoArray helps the identification of 21 HPV genotypes (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68) and CP8304. Of the 21 genotypes, 5 were classified as low risk (HPV 6, 11, 42, 43, 44) and the remaining HPV genotypes are classified as high-risk [14].

Statistical analysis

HPV positivity and all clinicopathological data, including age, gender, tumor stage, differentiation, tumor localization, and tobacco and alcohol use, underwent descriptive statistical analysis using SPSS v.10.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient demographics and clinicopathological findings

The study included laryngeal specimens obtained from 82 patients with laryngeal cancer and 11 laryngeal specimens reported as normal laryngeal mucosa. Among the 82 laryngeal cancer patients, 78 were male and 4 were female; mean age was 56.6 years (range: 40–75 years). Tumor localization included the supraglottis (n = 58 [70.7%]) and glottis (n = 24 [29.3%]). In all, 5 (6.1%) patients were clinically stage II, 38 (46.3%) were stage III, and 39 (47.6%) were stage IV. In total, 46 (56.1%) patients had no evidence of nodal involvement at the time of diagnosis. Tumors were histopathologically classified as well differentiated carcinoma (n = 33 [40.2%]), moderately differentiated carcinoma (n = 44 [53.7%]), and poorly differentiated carcinoma (n = 5 [6.1%]). Table 1 summarizes the clinical and pathological findings of the patients. A combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy was administered to all patients. Of all patients, 46 received induction chemotherapy followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy whereas 36 received only concomitant chemoradiotherapy. All chemotherapy protocols included an alkylating chemotherapeutic. The chemoradiotherapy protocol is shown in Table 2. During follow up, 35 (42.7%) patients had recurrence; the mean time from diagnosis to recurrence was 20.6 months (range: 6–50 months). Mean duration of follow-up in the patients without recurrence was 55 months (range: 24–120 months). Patients who had less than 2 year follow up were excluded. However, 1 of the patients who died 15 months after treatment with no evidence of recurrent disease and was included among the patients without recurrence. All 82 laryngeal cancer patients had a history of tobacco use, but most did not remember how long they smoked or how much they smoked; therefore, data were not analyzed according to quantity and duration of smoking.

In-situ hybridization and genotyping

Chromogenic In-Situ Hybridization (cISH) was performed to assess HR-HPV positivity. cISH findings were evaluated by 2 independent observers. None of the 82 laryngeal specimens obtained from patients with squamous cell carcinoma and none of the 11 laryngeal specimens with normal laryngeal mucosa exhibited a positive cISH staining pattern. Genotyping confirmed the cISH findings; none of the HPV types studied were present in any of the specimens.

Discussion

HPV infection has been shown to cause oropharyngeal cancer. However, the clinical significance of HPV infection in head and neck squamous cell cancer other than oropharygeal cancer is yet to be determined. The prevalence of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas that are HPV positive varies from 0% [2, 15, 16] to 75% [17]. This difference in the prevalence of HPV in laryngeal cancer has been explained by the sensitivity of diagnostic techniques, ethnic and geographical differences in patients, small study samples, low quality of the specimens, and differences in methods of sample storage and lesion localization [7, 11].

PCR and ISH are widely used HPV detection systems. ISH is commonly used to detect HPV in clinical biopsy specimens. Some studies report that PCR-based methods are more sensitive than ISH. Besides, PCR-based methods can yield false positive results, because they may not differentiate biologically irrelevant HPV from clinically significant HPV, whereas ISH correlates with biologically and transcriptionally active HPV, differentiating between clinically significant and non-tumorigenic HPV DNA [18,19,20,21]. HPV DNA PCR amplification only shows the existence, whereas ISH can show the integration of the viral DNA into the host genome [12, 22].

In the current study we used HR-HPV chromogenic ISH for detection of HR-HPV; however, none of the 82 laryngeal specimens of squamous cell carcinoma and none of 11 laryngeal specimens of normal laryngeal mucosa exhibited a positive cISH staining pattern. Although the reported prevalence of HPV positive squamous cell cancer of the larynx and hypopharynx varies widely, the literature generally indicates that the prevalence is higher than that observed in the present study, but some studies have also reported no HPV positivity or a very low prevalence of HPV positivity [2, 15, 23,24,25]. The study by Castellsague et al. including 1042 laryngeal cancer patients from 29 countries tested the specimens with PCR and a DEIA for the presence of HPV-DNA and samples containing HPV-DNA were further subject to HPV E6*I mRNA detection and to p16INK4a, pRb, p53, and Cyclin D1 immunohistochemistry [25]. This study, the largest exploring HPV attribution in head and neck cancers also found a small percentage of HPV positive laryngeal cancer cases. Some studies report that PCR-based methods are more sensitive than ISH and that PCR-based methods can yield false positive results [15, 18,19,20,21]. Such false positivity was avoided in the present study via use of cISH, which could be one of the reasons why HPV positivity was not observed in any of the present study’s laryngeal specimens. Gallo et al. [15] examined the role of HPV virus in laryngeal cancer using PCR and taking all necessary precautions to avoid false positive, as well as false negative findings. They reported that none of the 40 cases of squamous cell carcinoma showed presence of HPV genome, which supports the notion that earlier reports of high prevalence of HPV positivity might have been due to false positive results, and that many the majority of the laryngeal cancers are not related to HPV infection, as the current findings indicate.

The effect of tobacco use on laryngeal cancer is well-known, and we also reviewed the data and/or asked the patients about their tobacco use. Although the data were not very reliable because they were collected via self-report and the patients did not remember precisely how long they smoked or how much they smoked, all our patients had a history of tobacco use. Gheit et al. [23] reported that 75% of their patients harboring viral DNA had a history of tobacco use, and suggested that tobacco use could act together with HPV induced cancer formation. In the present study all patients had a history of tobacco use, but no HPV DNA was detected in any of the laryngeal specimens.

Some studies regarding head and neck cancer found out that HPV positivity was observed in younger patients compared to patients with HPV negative cancer [3, 4]. The current study’s patients were aged 40–75 years; none were considered young. Based on those earlier reports, it is possible that had the present study included younger patients, some with HPV positivity would have been identified [3, 4]. The transmission of HPV has been widely studied, and orogenital sexual contact and multiple sex partners were shown to increase the rate of transmission of the virus [25]. Roshan et al. [2] conducted a study in Iran and reported that HPV was not encountered in any of the specimens; neither in biopsies of patients with laryngeal cancer nor in biopsies obtained from healthy people, as in the present study. They attributed their findings to the rarity of high-risk sexual behavior in Iran. Their study differs from the present study as they only investigated HPV 16 and 18, whereas the present study investigated all HR-HPV types; in addition, the present study’s patient group was larger.

Earlier studies on HPV positivity in laryngeal cancer in Turkey reported that 7.4% [26] and 10.6% [24] of patients had HPV DNA. The difference in those reported percentages and that found in the current study might be secondary to differences is diagnostic techniques; Guvenc et al. [24] used hybrid capture to detect HPV and Gungor et al. [26] used PCR genotyping. These studies also included LR-HPV infections—another possible cause for the differences in findings, as when only HR-HPV infection was considered, the HPV positivity rate in Gungor et al.’s study was only 1% [26]. Other studies reported low rates of HPV positivity in normal laryngeal mucosa samples, of which many cases showed presence of low-risk HPV [12, 15, 18]. Similarly, none of the present study’s normal laryngeal mucosa specimens were HPV positive.

The present study is among the few from Turkey to investigate HPV infection in patients with laryngeal cancer, and compare it to HPV positivity in normal laryngeal tissue. The cISH technique used in the present study is not widely used for studying laryngeal cancer. A strength of the present study is that HPV negativity based on cISH was confirmed via genotyping. As some earlier studies reported, HPV positivity was not observed in any of the present study’s laryngeal specimens (both cancerous and normal) [2, 15, 16] indicating that HPV does not play a major role in the etiology of malignant laryngeal lesions. Nonetheless, the present study included only patients over 40 years old and a small overall population, which might be considered limitations. Lastly, as none of the present study’s laryngeal specimens were HPV positive, it was not possible to obtain any data on the effect of HPV positivity on recurrence, survival, or chemotherapy sensitivity.

Conclusion

The present findings suggest that HPV infection does not play a major role in laryngeal cancer; however, additional research is required to increase our understanding of the prevalence of HPV positivity in laryngeal cancer patients and the effect of HPV positivity on recurrence, survival, and chemotherapy sensitivity.

Abbreviations

- cISH:

-

Chromogenic In situ hybridization

- DEIA:

-

DNA enzyme immunoassay

- DFS:

-

Disease Free Survival

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded

- HPV:

-

Human Papilloma Virus

- HR-HPV:

-

High-risk Human Papilloma Virus

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- LR-HPV:

-

Low-risk Human Papilloma Virus

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- PPY:

-

pack per year

- SCC:

-

squamous cell carcinoma

References

Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–403.

Mohamadian Roshan N, Jafarian A, Ayatollahi H, Ghazvini K, Tabatabaee SA. Correlation of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma and infections with either HHV-8 or HPV-16/18. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:205–9.

Schwartz SR, Yueh B, McDougall JK, Daling JR, Schwartz SM. Human papillomavirus infection and survival in oral squamous cell cancer: a population-based study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:1–9.

Fakhry C, Gillison ML. Clinical implications of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2606–11.

Kumar B, Cordell KG, Lee JS, Prince ME, Tran HH, Wolf GT, Urba SG, Worden FP, Chepeha DB, Teknos TN, Eisbruch A, Tsien CI, Taylor JM, D'Silva NJ, Yang K, Kurnit DM, Bradford CR, Carey TE. Response to therapy and outcomes in oropharyngeal cancer are associated with biomarkers including human papillomavirus, epidermal growth factor receptor, gender, and smoking. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:S109–11.

Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, Westra WH, Chung CH, Jordan RC, Lu C, Kim H, Axelrod R, Silverman CC, Redmond KP, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35.

Stephen JK, Chen KM, Shah V, Havard S, Lu M, Schweitzer VP, Gardner G, Worsham MJ. Human papillomavirus outcomes in an access-to-care laryngeal cancer cohort. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:730–8.

Clayman GL, Stewart MG, Weber RS, el-Naggar AK, Grimm EA. Human papillomavirus in laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinomas. Relationship to survival. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120:743–8.

Morshed K. Association between human papillomavirus infection and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1017–23.

Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE, Shah KV, Sidransky D. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:709–20.

Torrente MC, Rodrigo JP, Haigentz M Jr, Dikkers FG, Rinaldo A, Takes RP, Olofsson J, Ferlito A. Human papillomavirus infections in laryngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2011;33:581–6.

Torrente MC, Ojeda JM. Exploring the relation between human papilloma virus and larynx cancer. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:900–6.

Schache AG, Liloglou T, Risk JM, Filia A, Jones TM, Sheard J, Woolgar JA, Helliwell TR, Triantafyllou A, Robinson M, Sloan P, Harvey-Woodworth C, Sisson D, Shaw RJ. Evaluation of human papilloma virus diagnostic testing in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: sensitivity, specificity, and prognostic discrimination. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6262–71.

Low HC, Silver MI, Brown BJ, Leng CY, Blas MM, Gravitt PE, Woo YL. Comparison of Hybribio GenoArray and Roche human papillomavirus (HPV) linear array for HPV genotyping in anal swab samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:550–6.

Gallo A, Degener AM, Pagliuca G, Pierangeli A, Bizzoni F, Greco A, de Vincentiis M. Detection of human papillomavirus and adenovirus in benign and malignant lesions of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:276–81.

Lindeberg H, Krogdahl A. Laryngeal cancer and human papillomavirus: HPV is absent in the majority of laryngeal carcinomas. Cancer Lett. 1999;146:9–13.

Morgan DW, Abdullah V, Quiney R, Myint S. Human papilloma virus and carcinoma of the laryngopharynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:288–90.

Witt BL, Albertson DJ, Coppin MG, Horrocks CF, Post M, Gulbahce HE. Use of in situ hybridization for HPV in head and neck tumors: experience from a National Reference Laboratory. Head Neck Pathol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-014-0549-1.

Stevens TM, Caughron SK, Dunn ST, Knezetic J, Gatalica Z. Detection of high-risk HPV in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: comparison of chromogenic in situ hybridization and a reverse line blot method. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2011;19:574–8.

Termine N, Panzarella V, Falaschini S, Russo A, Matranga D, Lo Muzio L, Campisi G (2008) HPV in oral squamous cell carcinoma vs head and neck squamous cell carcinoma biopsies: a meta-analysis (1988-2007). Ann Oncol 2008; 19:1681–1690.

Ha PK, Pai SI, Westra WH, Gillison ML, Tong BC, Sidransky D, Califano JA. Real-time quantitative PCR demonstrates low prevalence of human papillomavirus type 16 in premalignant and malignant lesions of the oral cavity. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1203–9.

Huang CC, Qiu JT, Kashima ML, Kurman RJ, Wu TC. Generation of type-specific probes for the detection of single-copy human papillomavirus by a novel in situ hybridization method. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:971–7.

Gheit T, Abedi-Ardekani B, Carreira C, Missad CG, Tommasino M, Torrente MC. Comprehensive analysis of HPV expression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Med Virol. 2014;86:642–6.

Guvenc MG, Midilli K, Ozdogan A, Inci E, Tahamiler R, Enver O, Sirin G, Ergin S, Kuskucu M, Divanoglu EO, Yilmaz G, Altas K. Detection of HHV-8 and HPV in laryngeal carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35:357–62.

Castellsagué X, Alemany L, Quer M, et al. HPV involvement in head and neck cancers: comprehensive assessment of biomarkers in 3680 patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(6):djv403. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv403.

Gungor A, Cincik H, Baloglu H, Cekin E, Dogru S, Dursun E. Human papilloma virus prevalence in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:772–4.

Funding

This study was funded by the Department of Scientific Research Projects. The funding body has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated or analysed during this study are not publicly available to protect the confidentiality of the subjects but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OOC, ES, SH, MC, IG, GGT analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the demographic data, oropharyngeal disease, p16 staining and ISH. ES, GGT performed the histological examination of the specimens. ES was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study and as some of the patients had deceased. The study protocol was approved and the informed consent was deemed unnecessary by the Hacettepe University Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Onerci Celebi, O., Sener, E., Hosal, S. et al. Human papillomavirus infection in patients with laryngeal carcinoma. BMC Cancer 18, 1005 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4890-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4890-8