Abstract

Background

The fullPIERS risk prediction model was developed to identify which women admitted with confirmed diagnosis of preeclampsia are at highest risk of developing serious maternal complications. The model discriminates well between women who develop (vs. those who do not) adverse maternal outcomes. It has been externally validated in several populations. We assessed whether placental growth factor (PlGF), a biomarker associated with preeclampsia risk, adds incremental value to the fullPIERS model.

Methods

Using a cohort of women admitted into tertiary hospitals in well-resourced settings (the USA and Canada), between May 2010 to February 2012, we evaluated the incremental value of PlGF added to fullPIERS for prediction of adverse maternal outcomes within 48 h after admission with confirmed preeclampsia. The discriminatory performance of PlGF and the fullPIERS model were assessed in this cohort using the area under the receiver’s operating characteristic curve (AUROC) while the extended model (fullPIERS +PlGF) was assessed based on net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) performances.

Results

In a cohort of 541 women delivered shortly (< 1 week) after presentation, 8.1% experienced an adverse maternal outcome within 48 h of admission. Prediction of adverse maternal outcomes was not improved by addition of PlGF to fullPIERS (NRI: -8.7, IDI − 0.06). Discriminatory performance (AUROC) was 0.67 [95%CI: 0.59–0.75] for fullPIERS only and 0.67 [95%CI: 0.58–0.76]) for fullPIERS extended with PlGF, a performance worse than previously documented in fullPIERS external validation studies (AUROC > 0.75).

Conclusions

While fullPIERS model performance may have been affected by differences in healthcare context between this study cohort and the model development and validation cohorts, future studies are required to confirm whether PlGF adds incremental benefit to the fullPIERS model for prediction of adverse maternal outcomes in preeclampsia in settings where expectant management is practiced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pre-eclampsia and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy complicate approximately 10% of pregnancies and contribute considerably to maternal, fetal, and newborn morbidity and mortality, worldwide [1]. Preeclampsia, defined broadly as hypertension with symptoms or signs of end-organ compromise, can lead to severe maternal complications (e.g., eclampsia, stroke, and liver dysfunction) and/or fetal complications (e.g., stillbirth and preterm delivery) [2, 3]. Early identification of women at high risk of these complications can guide care and prevent delays in treatment in order to prevent poor outcomes [2].

The fullPIERS risk prediction model was developed to facilitate early identification of women admitted with confirmed preeclampsia who are at greatest risk of developing severe maternal complications (e.g. eclampsia and stroke, see Appendix S1 for full list of outcomes) within 48 h of admission [4]. The published model (equation presented in Table 1) showed good discriminatory performance with an area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.88 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.84–0.92) upon internal validation and AUROC 0.81 (95% CI 0.75–0.86) upon external validation [5]. Thus, the model can aid in risk stratification, to allow for corticosteroid administration, transfer to higher care facilities, and plan for delivery for high-risk women.

Since the development of fullPIERS, new biomarkers have been introduced that could aid the identification of adverse outcomes in preeclampsia. One such biomarker is placental growth factor (PlGF), an angiogenic factor found in the maternal circulation [6, 7]. Plasma concentrations of PlGF are decreased in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia compared with uncomplicated pregnancies [6,7,8,9,10]. Several studies have tested the diagnostic ability of PlGF for women with suspected preeclampsia [6, 11,12,13]; the PELICAN study reported 96 and 98% sensitivity and negative predictive value, respectively, using PlGF <5th percentile, to predict confirmed preeclampsia and subsequent delivery within 14 days among women presenting with suspected preeclampsia before 35 + 0 weeks of gestation [11]. Similarly, in a cluster-randomized trial, PlGF < 100 pg/ml identified women (95 and 98% sensitivity and negative predictive value, respectively), with suspected preeclampsia who delivered within 14 days with confirmed pre-eclampsia [12]; these findings were consistent in the PreEclampsia Triage by Rapid Assay (PETRA) trial with a sensitivity of 92.5% and specificity of 63.8% [14]. However, fewer studies have aimed to investigate the prognostic value of PlGF in women with confirmed preeclampsia. In women with suspected preeclampsia, high discriminatory performance or strong likelihood ratios (LRs) have been demonstrated for PlGF for combined adverse maternal and fetal outcomes (usually the need for delivery with pre-eclampsia within 7–14 days) [10, 14,15,16,17,18]; however there are limited studies reporting on solely maternal outcomes [18,19,20,21,22].

Based on these reports, we evaluated whether addition of PlGF to fullPIERS could improve prediction of adverse maternal outcomes in women with confirmed preeclampsia.

Methods

This manuscript was prepared using the Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD) reporting guidelines for prediction models (Table S2) [23].

Study cohort

For this study, we used the PETRA data which included women that had PlGF measurements during admission [8, 14]. The original data originally consisted of a prospective cohort of 1217 women presenting with suspected symptoms and signs of preeclampsia with measurable PlGF values, at 24 maternity units in the United States of America (USA; N = 23) and Canada (N = 1) (November 2010 to January 2012) [14]. Women from the PETRA [8, 14] cohort who had confirmed preeclampsia were included in the study.

PlGF measurement

Maternal plasma samples were collected from eligible women between 20 and 35 weeks’ gestation, during the study recruitment. Samples were tested for PlGF using the Triage PlGF Test (Quidel Inc., San Diego, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We restricted our analyses to women with PlGF measured during hospital admission for confirmed preeclampsia (or at most 14 days before admission), to reduce the potential effect of changing PlGF concentration over time in the analyses and to be consistent with the other fullPIERS variable measurements [4, 5].

Definition of pre-eclampsia and outcomes

To be consistent with the fullPIERS model development study [5], preeclampsia was defined as hypertension plus one of proteinuria, hyperuricemia, or as HELLP (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzyme, Low Platelet) syndrome. A composite adverse maternal outcome was defined as the occurrence of maternal death or any maternal morbidity as determined by Delphi consensus (see online [https://pre-empt.cfri.ca/monitoring/fullpiers] and Appendix S1).

Statistical analyses

The distribution of participant characteristics included in this study were compared with those of women in the original fullPIERS development cohort, using Chi-squared and Mann–Whitney U tests (p-value of < 0.05) for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Univariable analyses were also carried out comparing characteristics of women in our study cohort with those in previous studies, according to low PlGF (< 100 pg/mL) and normal PlGF (≥100 pg/mL) [18].

Model extension with PlGF

PlGF measurements were converted to percentiles based on the reference range by gestational age interval [24]. Before inclusion in the fullPIERS model, we assessed the univariable discriminatory performance of PlGF. Using the most abnormal values of test results of the model predictors within 48 h of admission, a linear predictor variable was calculated for all the women in our study cohort using the fullPIERS model equation (1).

A logistic regression model was fitted with two variables: (i) the linear predictor and (ii) converted PlGF percentiles [7]. Hence, a new intercept and slope were estimated for the fullPIERS model as well as a regression coefficient for PlGF (Table 1). The extended model was then used to calculate the predicted probabilities of experiencing an adverse outcome for each woman and its performance was evaluated.

Prediction performance measures

The ability of PlGF to predict adverse maternal outcomes and the performance of the original fullPIERS model in the data were evaluated based on discrimination capacity. Discriminative ability was assessed using the AUROC and was interpreted using the following pre-specified criteria: non-informative (AUROC ≤0.5), poor discrimination (0.5 < AUROC ≤0.7), good discrimination (AUROC > 0.7) [25]. In addition to discrimination, the extended model performance was evaluated based on the net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) to assess the incremental value of PlGF compared with the performance of the original model [26,27,28].

NRI gives a summary of the overall improvement of sensitivity and specificity associated with addition of PlGF to fullPIERS. NRI integrates the “upward movement” (improved reclassification) and the “downward movement” (worse reclassification) for the women with adverse outcomes in the predicted risk groups with the reverse movements for the women without adverse outcomes [29, 30]. The sum of the differences between the two movements for the women with and without adverse outcomes is the NRI.

IDI is the difference in the discrimination slope between the original model and the extended model. The discrimination slope is calculated as the difference between the average predicted probabilities of the women with and without adverse maternal outcomes. This measurement also incorporates the NRI across all possible cut-offs.

All analyses were done in R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

The extension cohort included only a subset of women who met our inclusion criteria (N = 541), as previously described (Fig. 1).

Demographics

The women in the extension cohort (compared with those in the original fullPIERS development cohort) were different in a number of ways (Table 2). In general, women admitted with preeclampsia in the original fullPIERS cohort were known to be managed expectantly, whereas those admitted in the extension cohort settings (mostly in the USA) were more likely to be delivered; this was also evident in the shorter admission-to-delivery interval. On average, the women in the extension cohort were younger with lower blood pressure measurements and presenting with earlier-onset of preeclampsia than the women in the fullPIERS cohort. They were also more likely to be multiparous, smokers, and receive magnesium sulfate; have a shorter admission-to-delivery interval with early-onset preeclampsia (gestational age [GA] < 34 weeks); and have babies with lower birth weight, compared with the fullPIERS cohort. There were no meaningful differences in the proportions of multifetal pregnancies or treatment with antihypertensive medication. Adverse maternal outcomes occurred in 8.1% of women within 48 h of admission, 9.6% within 7 days of admission, and 10.5% at any time during admission.

PlGF was classified as low (< 100 pg/ml) in 485 women (89.6%) (Table 3). Low maternal PlGF concentrations were more likely among women with earlier onset of preeclampsia, higher blood pressure, and babies with lower birth weight. Low PlGF was present in almost all women who went on to experience adverse maternal (N = 53/57, 93.0%) at any time during admission.

Prediction of adverse maternal outcomes after adding PlGF to fullPIERS

In our analyses, the original fullPIERS model (AUROC 0.67 [95% CI 0.58–0.76]) and PlGF alone (AUROC 0.60 [95% CI 0.52–0.67]) showed poor discriminatory performance for prediction of adverse maternal outcomes within 48 h of admission in the extension cohort (Fig. 2). Addition of PlGF to fullPIERS neither altered the odds of an adverse maternal outcome (OR 0.98 [95% CI 0.99–1.00]) for every percentile increase in PlGF (Table 1), nor discriminatory performance (AUROC 0.67 [95% CI 0.59–0.75]) (Fig. 2).

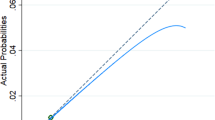

With addition of PlGF to fullPIERS, using a threshold of ≥10% for the calculated predicted probabilities, there were eight upward movements of women with adverse maternal outcomes into the high-risk category and two fewer cases without adverse maternal outcomes in the highest-risk category compared with the classification using the original model (Table 4). The overall improvement in specificity was 11.9%, with a decrease of 18.4% in sensitivity using the extended model. Thus, the NRI was − 8.7, indicating no overall improvement in reclassification of risks. The discrimination slope for the extended model (fullPIERS plus PlGF) was 0.03, compared with 0.09 for the original model (Fig. 3). The IDI was − 0.06, also indicating no meaningful improvement in discrimination.

Discussion

Principal findings

In our study comprised of women with confirmed preeclampsia from tertiary hospitals in well-resourced settings, prediction of adverse maternal outcomes was not improved by addition of PlGF to fullPIERS. Of note is that fullPIERS performed poorly in this extension cohort compared with other studies where the AUROC was > 0.75 [4, 5, 31].

Results compared to other studies

In the original fullPIERS model development cohort, the model performed well in the prediction of adverse maternal outcomes (AUROC 0.88, 95% CI 0.84–0.92). Similarly, in methodologically rigorous and robustly conducted temporal and external validation studies [4, 5], the model also performed well, (AUROC of 0.82 (95% CI 0.76–0.87) for temporal and 0.81 (95% CI 0.75–0.86) for external validation). In another study assessing the model in women with early-onset of pre-eclampsia, the discriminatory performance of the model was AUROC of 0.80 (95% 0.75–0.86). However, in this study, the model performance was lower, even upon the addition of PlGF. These findings are similar to an abstract assessing the fullPIERS model in a cohort of women admitted with pre-eclampsia in the United States, which reported a lower performance (AUROC: 0.68, 95% CI 0.60–0.76) for adverse maternal outcomes [32]. The fullPIERS was developed and externally validated in settings where expectant management was the practice. We hypothesize that this difference in model performance may be due to differences in pre-eclampsia management between the original fullPIERS setting and the other hospital settings in the USA. Further research to test this hypothesis would be valuable.

In contrast with our study, the PARROT trial reported lower incidence of adverse maternal outcomes in women with suspected preeclampsia (rather than confirmed preeclampsia as studied here), when PlGF values were revealed to the clinician, compared with the concealed group [12]. However, in the PETRA study [14] (from which our study extension cohort was derived), clinicians were masked to PlGF values and, therefore, could not have been influenced by the results. Although the PARROT trial results suggest that clinicians might positively respond to low PlGF possibly by increasing surveillance for women potentially at higher risk of adverse outcomes, it did not assess the prognostic value of PlGF for adverse maternal outcomes in women with preeclampsia.

Strengths

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the addition of PlGF to fullPIERS for prediction of adverse maternal outcome in women with confirmed preeclampsia. Our use of a composite outcome that warrants consistent clinical action makes the results of our study robust and clinically relevant. This evaluation of an externally-validated model provides benchmark performance estimates against which comparisons can be made for different locations and upon addition of new biomarkers.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study was having limited power due to a relatively small sample size and number of adverse outcomes. Based on our small sample size, we did not re-estimate the fullPIERS model coefficients when extending the model with PlGF as this would lead to significant overfitting of the model in the data set [33]. However, this may have been necessary if the addition of PlGF were to change the predictive coefficients of the other variables in the model. Second, we may have underestimated the relationship between PlGF and adverse outcome because some PlGF measurement results were carried forward (by no more than 14 days), rather than ideally have been measured within 48 h of admission. Third, practice varied in our study settings; expectant care (pregnancy prolongation) was less frequently practised in the extension cohort setting, so the natural history of disease was truncated by expedited delivery. In contrast, in the fullPIERS model development cohort, expectant care was the norm, resulting in a longer admission to delivery interval (mean of 11 days, compared with 5 days in the extension cohort – Table 2).

Clinical implications

Despite our study limitations outlined above, there are possible explanations for the poor predictive performance for adverse maternal outcomes observed in our study. PlGF is a marker of placental dysfunction; therefore, this angiogenic factor may be more reflective of the initiation of preeclampsia (i.e. from suspected to established pre-eclampsia), rather than the progression or disease severity after the diagnosis of preeclampsia. Thus, PlGF appears to be less useful as a prognostic marker for women with confirmed pre-eclampsia in settings where less expectant management is practised.

Of note, almost 90% of included women had low PlGF suggesting a higher risk cohort. Such a case-mix is likely to reduce prediction performance, as more population homogeneity is associated with lower discrimination [34]. However, the high proportion of low PlGF values supports in the role of this angiogenic marker as a risk marker of preeclampsia development; women with low PlGF were more likely to have higher blood pressure measurements and experience worse neonatal outcomes.

Conclusion

In our study, the addition of PlGF did not improve the performance of the fullPIERS model in predicting adverse maternal outcomes in the extension cohort. Given the poor performance of fullPIERS for prediction of adverse maternal outcomes in this study compared with previous studies, we speculate that our findings may relate to differences in case-mix and/or context between this cohort and the original fullPIERS model development cohort. These data suggest that fullPIERS may not be predictive of maternal outcome in settings where expedited delivery for preeclampsia is the standard of care. Given the paucity of relevant datasets for these analyses, future work is needed to evaluate the incremental benefit of adding PlGF or other biomarkers e.g. sFLT-1 to fullPIERS, a model based on routinely collected maternal history, physical examination, and laboratory variables, especially in healthcare settings with expectant management.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Quidel triage Inc. (https://www.quidel.com/immunoassays/triage-test-kits) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Quidel triage Inc.

Abbreviations

- PlGF:

-

Placental growth factor

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- AUROC:

-

Area under the receiver’s operating characteristic curve

- NRI:

-

Net reclassification index

- IDI:

-

Integrated discrimination improvement

- PETRA:

-

PreEclampsia Triage by Rapid Assay

- GA:

-

Gestational age

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- sFLT-1:

-

Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1

References

Hutcheon JA, Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and the other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25(4):391–403.

von Dadelszen P, Magee LA. Preventing deaths due to the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36:83–102.

Magee LA, Pels A, Helewa M, Rey E, von Dadelszen P. Canadian hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) working group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2014;4(2):105–45.

von Dadelszen P, Payne B, Li J, et al. Prediction of adverse maternal outcomes in pre-eclampsia: development and validation of the fullPIERS model. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):219–27.

Ukah UV, Payne B, Karjalainen H, et al. Temporal and external validation of the fullPIERS model for the prediction of adverse maternal outcomes in women with pre-eclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019;15:42–50.

Kleinrouweler C, Wiegerinck M, Ris-Stalpers C, et al. Accuracy of circulating placental growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and soluble endoglin in the prediction of pre-eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2012;119(7):778–87.

Thadhani R, Mutter WP, Wolf M, et al. First trimester placental growth factor and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and risk for preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(2):770–5.

Woelkers DA, von Dadelszen P, Sibai B. 482: diagnostic and prognostic performance of placenta growth factor (PLGF) in women with signs or symptoms of early preterm preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):S264.

Hassan MF, Rund NMA, Salama AH. An elevated maternal plasma soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 to placental growth factor ratio at midtrimester is a useful predictor for preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2013;2013:1–8.

Ukah UV, Mbofana F, Rocha BM, et al. Diagnostic performance of placental growth factor in women with suspected preeclampsia attending antenatal facilities in Maputo, Mozambique. Hypertension. 2017;69(3):469–74.

Chappell LC, Duckworth S, Seed PT, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of placental growth factor in women with suspected preeclampsia: a prospective multicenter study. Circulation. 2013;128(19):2121–31.

Duhig KE, Myers J, Seed PT, et al. Placental growth factor testing to assess women with suspected pre-eclampsia: a multicentre, pragmatic, stepped-wedge cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1807–18.

Agrawal S, Shinar S, Cerdeira AS, Redman C, Vatish M. Predictive performance of PlGF (placental growth factor) for screening preeclampsia in asymptomatic women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2019;74(5):1124–35.

Barton JR, Woelkers DA, Newman RB, et al. Placental growth factor predicts time to delivery in women with signs or symptoms of early preterm preeclampsia: A prospective multicenter study. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(3):259.e1–259.e11.

Álvarez-Fernández I, Prieto B, Rodríguez V, Ruano Y, Escudero AI, Álvarez FV. N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide and angiogenic biomarkers in the prognosis of adverse outcomes in women with suspected preeclampsia. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;463:150–7.

Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Savasan ZA, et al. Maternal plasma concentrations of angiogenic/anti-angiogenic factors are of prognostic value in patients presenting to the obstetrical triage area with the suspicion of preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(10):1187–207.

De Oliveira L, Peraçoli JC, Peraçoli MT, et al. sFlt-1/PlGF ratio as a prognostic marker of adverse outcomes in women with early-onset preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2013;3(3):191.

Ukah UV, Hutcheon JA, Payne B, et al. Placental growth factor as a prognostic tool in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2017;70(6):1228–37.

Ghosh SK, Raheja S, Tuli A, Raghunandan C, Agarwal S. Association between placental growth factor levels in early onset preeclampsia with the occurrence of postpartum hemorrhage: a prospective cohort study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2012;2(2):115–22.

Palomaki GE, Haddow JE, Haddow HRM, et al. Modeling risk for severe adverse outcomes using angiogenic factor measurements in women with suspected preterm preeclampsia. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35(4):386–93.

Leaños-Miranda A, Campos-Galicia I, Ramírez-Valenzuela KL, Chinolla-Arellano ZL, Isordia-Salas I. Circulating angiogenic factors and urinary prolactin as predictors of adverse outcomes in women with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2013;61(5):1118–25.

Rana S, Schnettler WT, Powe C, et al. Clinical characterization and outcomes of preeclampsia with normal angiogenic profile. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2013;32(2):189–201.

Moons KGM, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(1):W1–73.

Saffer C, Olson G, Boggess KA, et al. Determination of placental growth factor (PlGF) levels in healthy pregnant women without signs or symptoms of preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2013;3(2):124–32.

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36.

Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):128–38.

Steyerberg EW, Pencina MJ, Lingsma HF, Kattan MW, Vickers AJ, Van Calster B. Assessing the incremental value of diagnostic and prognostic markers: a review and illustration. Eur J Clin Investig. 2012;42(2):216–28.

Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Statistical methods for assessment of added usefulness of new biomarkers. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2010;48(12):1703–11.

Payne BA, Hutcheon JA, Dunsmuir D, et al. Assessing the incremental value of blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) in the miniPIERS (pre-eclampsia integrated estimate of RiSk) risk prediction model. JOGC. 2015;37(1):16–24.

Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Pencina KM, Janssens ACJW, Greenland P. Interpreting incremental value of markers added to risk prediction models. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(6):473–81.

Ukah UV, Payne B, Hutcheon JA, et al. Assessment of the fullPIERS risk prediction model in women with early-onset preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2018;71(4):659–65.

Hadley EE, Poole A, Herrera SR, et al. 472: external validation of the fullPIERS (preeclampsia integrated estimate of RiSk) model. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(1):S259 -S260-S260.

Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJC, Habbema JDF. Substantial effective sample sizes were required for external validation studies of predictive logistic regression models. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(5):475–83.

Steyerberg EW. SpringerLink ebooks - mathematics and statistics. Clinical prediction models: A practical approach to development, validation, and updating. 1. Aufl. Ed. New York: Springer; 2009. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77244-8.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all who have contributed to data collection, expertise and collaboration in this study: PIERS data collection team (Vivian Cao, Emma von Dadelszen, Lillian Cao, Katherine Thomas, Phenicia Azurin, Matthew Haslam, Benita Okocha, Elizabeth Wilcox), Paul Sheard and the PETRA Study group.

Funding

This project was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN#136985). The funding source had no involvement in any part of the study design, interpretation or manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

This study was conceived by UVU, LAM and PvD, and data acquisition by PvD. Manuscript writing and data analyses were conducted by UVU, while study design, data interpretation, and critical review were conducted by BAP, JAH, LC, PS, FICR, and JM. The study was jointly supervised by LAM and PvD. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the individual study sites in the original study by Quidel triage Inc [14] while a data sharing agreement was made between the University of British Columbia and Quidel triage Inc. to access anonymized data for this study. This study was part of a multinational validation study approved by the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board (CREB no: H07–02207).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: S1.

List and definitions of PIERS maternal adverse Outcomes. S2. TRIPOD checklist for reporting prediction model development and validation studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ukah, U.V., Payne, B.A., Hutcheon, J.A. et al. Placental growth factor for the prognosis of women with preeclampsia (fullPIERS model extension): context matters. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 668 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03332-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03332-w