Abstract

Background

For over 25 years cord blood has been used as an alternative to bone marrow for therapeutic use in conditions of the blood, immune system and metabolic disorders. Parents can decide if they would like to privately store their infant’s cord blood for later use if needed or to publicly donate it. Parents need to be aware of the options that exist for their infant’s cord blood and have access to the relevant information to inform their choice. The aim of this paper is to identify parent’s knowledge and awareness of cord blood donation, private banking options and stem cell use, and parent sources and preferred sources of this information.

Methods

An integrative review was conducted using several electronic databases to identify papers on parents’ knowledge, attitudes and attitudes towards umbilical cord blood donation and banking. The CASP tool was used to determine validity and quality of the studies included in the review.

Results

The search of the international literature identified 25 papers which met review inclusion criteria. This integrative review identified parents’ knowledge of cord banking and/or donation as low, with awareness of cord blood banking options greater than knowledge. Parents were found to have positive attitudes towards cord blood donation including awareness of the value of cord blood and its uses, with the option considered to be an ethical and altruistic choice. Knowledge on cord blood use were mixed; many studies’ participants did not correctly identify uses. Information sources for parents on cord blood was found to be varied, fragmented and inconsistent. Health professionals were identified as the preferred source of information on cord blood banking for parents.

Conclusions

This integrative review has identified that further research should focus on identifying information that expectant parents require to assist them to make informed choices around cord blood banking; and identifying barriers present for health professionals providing evidence based information on cord blood use and banking options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

For over 25 years cord blood has been used as an alternative to bone marrow for therapeutic use in conditions of the blood, immune system and metabolic disorders [1]. Cord blood is now one of the main haematopoietic stem cell sources [2]. Umbilical cord blood banking is the process of collecting and storing umbilical cord blood, in the immediate period after the birth of a baby. Cord blood can be collected and stored either publicly or privately.

Public cord blood banks operate in all developed countries, and within most developing countries. By 2014, the international cord blood banking network comprised over 160 public cord blood banks in 36 countries, with over 731,000 umbilical cord blood units stored [3]. Public cord blood banks collect, transport, process, test and store cord blood units which have been altruistically donated for allogeneic use, at no financial cost to the donating parents [4,5,6,7,8,9]. The donated cord blood unit is not reserved for the use of the donating family, who relinquish their rights of ownership of the blood to the banking facility [10].

Private cord blood banks charge parents a fee for the collection, processing and storage of their infant’s cord blood for exclusive autologous or family use [4, 8, 9, 11, 12]. Some private cord blood banks now also store cord tissue.

Parents can decide if they would like to privately store their infant’s cord blood for later use if needed, publicly donate it, defer cord clamping to allow their infant to receive optimal volumes of cord blood at birth or to discard the remaining cord blood with the placenta after birth. Parents need to be aware of the options that exist for their infant’s cord blood and have access to the relevant information to inform their choice. Parents’ knowledge and understanding of cord blood banking and donation has been reported to be low and little is known about their source of information on this topic and the quality of the information provided [13,14,15]. Thus, accuracy of information is difficult to assess and there is limited understanding of how parents use this information to inform their decision making about cord blood banking and donation.

Methods

Aim

In this integrative review, we aimed to identify a) parent’s knowledge and awareness relating to cord blood donation, private banking options and stem cell use; b) sources of information received, and c) parents’ perceptions of appropriate sources and personnel to provide this information. The rationale for the integrative review was to identify gaps in knowledge and to provide direction for the development of antenatal education frameworks for parents in this important and evolving field of cord blood banking and cord blood use.

Methodology

The integrative method chosen for this review allowed for rigorous evaluation of the strength of the evidence from a combination of diverse methodologies (Whittmore and Knafi 2005), and identification of gaps in the literature and areas for further research [16]. The five stages model [17] of problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation [16], was used as a framework to guide this integrative review.

Literature search

Databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, MIDIRS, CINAHL and Google Scholar using search terms: cord blood banking, cord blood donation, cord blood stem cells, women’s knowledge, expectant parents’ knowledge, parent/parental knowledge, sources. Publication date limits were set between 1991 and July 2017. Cord blood banking was reported to have commenced in 1991 [18]; no papers were found on this topic prior to 1998.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the review consisted of original research studies that investigated and reported parents’ knowledge, awareness and attitudes of cord blood donation and banking options, written in the English language. The initial search was conducted by the first author who identified the potential studies for inclusion based on title and abstract, with all papers for inclusion discussed and agreed upon by co-authors.

Exclusion criteria included papers not available in the English language, discussion papers, papers reporting on knowledge and awareness of embryonic stem cells, and papers which reported only on women’s choices and reasons for choice.

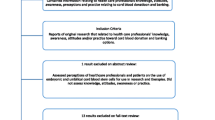

Figure 1 details the structured search conducted, including the search strategy and inclusion process applied to the peer reviewed literature which was included in this integrative review.

Data evaluation

Each article was read and summarised to identify the key points and common themes. Following the identification of these, the similarities and differences between studies were compared. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools appropriate for the study designs were used to determine the quality of the studies [19]. Quantitative studies were assessed using the CASP Cohort Study Checklist (see Additional file 1). Qualitative and mixed methods studies were assessed using the CASP Qualitative Checklist (see Additional file 2). No papers were excluded because of their validity or quality.

Data analysis

A total of 31 articles were retrieved that provided description relating to parents’, expectant parents’ or pregnant women’s knowledge and awareness of cord blood banking and donation. Only one paper retrieved also explored pregnant women’s and/or expectant parents’ knowledge and awareness of cord tissue banking [20]. Six papers were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, or aims of this integrative review [11, 21,22,23,24,25].

Thematic analysis [26] was used to identify emerging domains and themes in the literature, with three common domains identified: cord blood banking options, cord blood uses, and information sources.

Findings

This search of the international literature identified 25 papers of parents, pregnant women’s and expectant parents’ knowledge and awareness of cord blood banking and donation which met the review inclusion criteria [13,14,15, 18, 20, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Studies selected for inclusion in the review included empirical studies using qualitative (n = 5), quantitative (n = 18) and mixed methodologies (n = 2).

Overall, papers exploring pregnant women’s and expectant parents’ knowledge and awareness of cord blood donation and banking, were conducted in 15 countries: North America and Canada [13, 15, 18, 27, 28, 31], Europe and the United Kingdom [14, 29, 30, 32, 34, 36, 41, 42, 46], Australia [40], Asia and the Middle East [33, 35, 37, 43,44,45], Africa [38, 39] and one international study involving countries in Europe, Asia, Australasia, the Americas and Africa [20].

This integrative review included descriptive quantitative studies predominantly using survey designs [13,14,15, 20, 22, 30, 33,34,35,36, 39,40,41,42,43, 46]; qualitative studies predominantly comprising focus groups and interviews [18, 27,28,29, 31, 37]; or mixed method approaches using a survey design with interviews and focus groups [32, 38] to describe knowledge, awareness and attitudes of cord blood donation and banking options. Table 1 summarises the papers included in this review.

Three domains pertaining to pregnant parents’ knowledge, awareness and attitudes were identified: a) cord blood banking and donation; b) cord blood use; and c) cord blood information sources and preferred information sources. Cord blood banking and donation options encapsulated three themes: knowledge, awareness and attitudes. The second domain, cord blood use, comprised two themes: knowledge and awareness. The final domain, information sources, was also divided into two themes: actual sources and preferred sources of information on cord blood banking and donation.

Cord blood banking and donation

Seven papers investigated and reported on cord blood banking awareness [13, 15, 31, 39,40,41, 46]. Four studies reported a high level of awareness, with around 70% of participants reporting awareness of the topic [15, 40, 41, 46]. Women of lower education levels, age 25 years or less, or of an ethnic minority background were factors associated with less awareness of banking and donation [15, 40].

Three papers reported low awareness of cord blood banking and donation [13, 31, 39]. Participants who had heard about cord blood banking expressed considerable confusion between public and private banking options [31], with cord blood donation having the least awareness reported in North America [13, 31].

Thirteen studies reported on cord blood banking and donation knowledge [14, 15, 18, 27, 28, 32,33,34, 37, 41, 43,44,45,46], with most studies assessing knowledge by participant self-report, as opposed to knowledge being measured by assessment of associated facts. Ten studies identified parent-reported suboptimal knowledge about collection and storage options for cord blood [15, 18, 27, 28, 32,33,34, 37, 43, 44], and of parents being minimally informed about cord blood banking and donation options [15, 28, 32,33,34, 37, 44, 45].

Exceptions to these low knowledge findings were reported by four studies, with more than 70% of participants of three studies reported to be knowledgeable about cord blood banking and donation [14, 41, 46]. Findings from early postpartum women (n = 320) surveyed by Kim et al. (2015) on their knowledge and attitudes of storage, donation and disposal of cord blood suggested that a high level of knowledge about cord blood was associated with women opting for cord blood donation.

Ten papers investigated parents’ attitudes towards cord blood banking and donation with samples including pregnant women, expectant parents and new parents [14, 28, 29, 32, 34, 35, 41, 42, 44, 46]. Overall, the findings from these studies indicated that parents were more inclined to support donation than private cord blood banking [14, 28, 32, 34, 35, 42, 45]. Key themes of parent attitudes towards donation and storage of cord blood included altruism, ethical practice, duty to society and insurance for the baby. Only one paper reported low regard for altruism or public benefit surrounding cord blood donation, however this may be attributed to lack of awareness of cord blood donation as public cord blood banking was not available at the time of this study’s data collection [45].

Several papers found parents to be positive towards cord blood banking [29, 41, 44, 45]. Reasons given for private cord blood banking included insurance for their baby [44], the cord blood may be needed in the future and they may have future regret of not storing their baby’s cord blood [29].

Cord blood use

Five papers reported on cord blood use awareness [13, 31, 38, 41, 46], with only one paper reporting high awareness, which included participants who were already parents [41]. Three studies used mixed methods and reported that considerable proportions of the parent population had relatively low awareness relating to uses of cord blood [13, 31, 38].

Nine papers reported knowledge of cord blood use [13, 27,28,29,30, 33, 35, 36, 46] and knowledge deficits were identified. Treatment of blood cancers was the most commonly known use of cord blood [13, 29, 30, 35], with over 50% of participants correct in their responses in studies by Fox and colleagues (n = 70%) [14] and Palten and Dudenhausen (50–65%) [26]. Limited knowledge was reported for other uses [13, 30, 36], including the likelihood of use of cord blood stem cells [28, 33]. Matijevic and Erjavec (2016) reported 95% of participants in their study self-reported knowledge of cord blood treatments as either insufficient or basic [46].

Cord blood information

Source of information

Source of cord blood banking information was investigated by 16 of the reviewed papers [13,14,15, 20, 28, 30, 31, 34,35,36, 39, 40, 42, 44,45,46]. The main sources of parent information were hospitals; health professionals, including antenatal classes; media and magazines; cord blood banks; and family and friends. Table 2 summaries the sources of information reported in the studies reviewed.

Six authors reported health professionals and/or antenatal classes were the main source of information on cord blood banking [14, 20, 36, 41, 42, 44], with a further two authors reporting these were the second most common sources [39, 40]. Health professionals, particularly doctors, were identified as important informers of cord blood banking options [20, 36, 42, 45]. Receiving this information from a health professional significantly influenced the parental decision to store cord blood [20].

Four authors reported low numbers of participants had received cord blood information from health professionals [15, 34, 35, 45, 46], and a further study found that participants had to actively enquire in order to receive information on cord blood donation [14].

Print and electronic (including internet) media and advertising were the main information source of cord blood banking reported in six studies [15, 30, 34, 35, 39, 46], and was the second most common source in two further papers [36, 40] after health professionals [36] and private cord blood banks [40].

Four studies listed cord blood banks as a source of cord blood banking information [13, 20, 30, 40], with Jordens and colleagues [36] reporting this was the main source for their participants. Private banking information was reported as a more common source of information compared to public banks [13, 30]; one study reported that almost half of their sample indicating that information from private cord blood banks was influential in their decision to store cord blood [20].

Six reports noted family and friends to be a source of information [14, 20, 36, 39, 42, 47], though only one paper stated this was their main source [20]. Three studies combined ‘family, friends and media’ as a single information source category [15, 28, 32]. These studies reported similar findings with approximately 20% of participants identifying this category as a source of cord blood banking information and an influence in their decision-making [15, 32, 38].

Preferred source of information

Five papers reported on participants preferred source of information on cord blood banking and donation [28, 29, 31, 33, 40, 45]. Four studies listed antenatal health professionals, including antenatal classes, as the most important and preferred source [29, 31, 33, 40, 45]. Only one paper reported cord blood banks as a preferred source of information [33]. Table 2 displays the preferred information sources reported by participants of studies included in this review.

Discussion

Cord blood banking and donation has been an option for parents for the past quarter century, yet an understanding of knowledge and awareness of these options, and consistency of information provided to parents, remains low. This is the first integrative review to explore parents’ knowledge, awareness and attitudes towards cord blood banking and donation, and parent sources, and preferred source, of information on this topic.

This integrative review identified parents’ knowledge of cord banking and/or donation as generally low [18, 27, 28, 32,33,34, 37, 44,45,46]. Higher knowledge levels were identified where participants had previously donated cord blood and where participants had been provided with information on these options by their antenatal health care provider or in antenatal classes [14, 41, 44]. This finding highlighted the importance of providing parents with this information as part of routine antenatal education. Overall, awareness of cord blood banking options was found to be higher than knowledge in this integrative review [15, 41, 47]. Like knowledge findings, this may be attributed to the availability of information provided at birthing facilities, and the level of education of participants [15, 40, 41].

Positive attitudes towards cord blood donation among parents were found, with the option considered to be an ethical [42] and altruistic choice for parents [14, 28, 34, 35, 41]. This could be indicative that cord blood donation has a moral association, and this finding may be important when health professionals discuss this option with parents as they may feel pressure or an obligation to choose this option. Positive attitudes towards private cord blood banking were also found, with only one study reporting negative findings [32]. Participants who chose to privately store their infant’s cord blood did so because they viewed this option as an investment for future use, insurance or protection for their child or family [28, 29, 34, 35, 44]. The desire of parents to do the best for their children and provide for their future may influence their interpretation of the importance of the scientific benefit on storing cord blood stems cells for future health protection, and illustrates the emotional element frequently attached to this option.

Knowledge on cord blood use among study participants was mixed. Over 50% of participants in many of the studies could not correctly identify uses of cord blood [13, 18, 27, 29, 30, 33, 36, 46]. This lack of knowledge emphasises the uncertainty about the source and the quality of the information being provided. When knowledge was self-reported by participants, general uses for cord blood was higher than specific uses [29, 30, 36], with treatment of blood cancers the highest correct response reported [14, 26].

Awareness among parents of the value of cord blood and cord blood uses was found to be less than knowledge levels of cord blood value and use. We identified that the provision of information by health professionals greatly influenced awareness of the value of cord blood and its’ potential uses. This finding again emphasises the need for information to be provided as part of routine antenatal care.

In this integrative review, we found that there was inconsistency in information provided to parents about cord blood banking and cord blood use. This inconsistency created awareness and knowledge deficits and arguably prevents parents from making informed choices. This is an important finding; in Australia, the Health and Safety commission have identified involving consumers in health care choices is associated with better client experience and promotes client centered care [48].

Information sources for parents on cord blood was found to be varied, fragmented and inconsistent [14, 20, 35, 40]. This inconsistency of information is concerning because for parents to make informed choices about cord blood banking or donation they need appropriate, relevant, objective information that is accurate, valid, regulated and based on the latest evidence in a variety of consumer-friendly formats through trustworthy sources [49].

Health professions were identified as the preferred source of information on cord blood banking for parents [28, 29, 31, 33, 40, 45]. The views of clients are among many factors that influence change to health services [50] and it is imperative that information on cord blood banking and donation is considered as part of routine antenatal education for parents.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The integrative approach chosen for this review of parent knowledge and awareness of cord blood banking, donation and cord blood banking, including sources and preferred sources of information, allowed for the inclusion of a diverse range of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies with participant samples from nations representing most world continents. Despite the literature review being extensive, inclusive of published studies meeting eligibility criteria since cord blood banking became available in 1991, this integrative review was limited to studies published in the English language only. Different terminology and sampling descriptions (pregnant women and / or parent / couples’ knowledge) used across studies, and a lack of clarity and consistency within studies relating to study aims and methods reported, limited interpretation of some study results.

The papers included in this review varied significantly in sample size (n = 30 to 1873), but this may have been driven by the research approach chosen [18, 31, 32, 37]. Survey tools to measure knowledge, awareness and attitudes were poorly described or not validated in some studies [14, 32, 35,36,37, 43, 46], with only two studies using the same (or modified version) tool [13, 30].

Several papers reported on awareness, not knowledge, as indicated in their title or abstract [29, 30, 32, 40, 41] or on knowledge, when awareness was indicated [34]. The findings of some studies were context specific and may not be generalised [14, 18, 31, 35,36,37], or participants did not have access to both cord blood banking and donation which may have influenced study findings [15, 27, 28, 33, 34, 39].

Implications for practice, education and research

In this integrative review, inconsistencies, and uncertainty in knowledge and awareness that parents have regarding cord blood use and banking options have been highlighted. These findings are indicative of the need for expectant parents to be informed of the cord blood banking options available to them by their antenatal care providers and/or at their birthing facility so that they can make an informed decision about what option is appropriate for their family circumstances. Maternity care policy and practice evolve with the emergence of new research evidence [49]; health services therefore need to be responsive to client and consumer input and needs [48] and involve clients in health care and informed decision making.

Research

Parent knowledge of cord blood banking options and cord blood use has been identified as poor. This integrative review identified that parents have a lack of knowledge about the options of cord blood banking and donation, and the uses of cord blood. There is lack of clarity and consistency in the information provided for parents on cord blood banking, donation and cord blood use. Future research is needed to explore health professionals’ knowledge of, and attitudes towards, cord blood banking, donation and cord blood use and how this impacts on the information that they provide to expectant parents in their care. The option of cord blood banking and donation has been available to parents for over 25 years so it is timely to investigate where the gaps in health professionals’ knowledge lie.

Practice

Information on cord blood banking and cord blood use is not a standard element of antenatal education and this is concerning because parents require this information to make a fully informed choice of their options regarding their infant’s cord blood following birth. We argue that there is a need for health professionals to provide accurate and evidence-based information to parents. This integrative review has demonstrated that information provision to expectant parents by health professionals on the topic of cord blood banking and donation is not a consistent part of antenatal education. Research is needed to identify and understand barriers to the information provision to parents on cord blood banking and donation, and why this important topic is not yet a standardised part of antenatal education.

Education

Health professionals are the parent preferred source of cord blood banking information. It is vital that health professionals are educated and informed of all aspects and elements of cord blood banking to enable them to provide appropriate information to parents. We argue that cord blood banking should be incorporated into health professional curricula and antenatal education.

Conclusion

Cord blood banking is complex and often poorly understood by parents and health professionals. This integrative review makes an important contribution to the body of knowledge in this field by identifying knowledge, highlighting gaps and suggesting direction for future research, practice and education in relation to cord blood banking and donation and cord blood use.

Significant gaps in parents’ knowledge and awareness of cord blood banking have been identified in this review of current evidence. This is an important topic and one that requires parents to make informed and rationale choices. For this to occur, information provided needs to be accurate, objective valid, timely and appropriate, and supplied by parent preferred sources. As identified in this integrative review, currently this is not the case.

This integrative review has identified that further research should focus on identifying the information expectant parents would like to receive to assist them to make an informed choice around cord blood banking and to identifying the barriers to health professionals providing this evidence-based information on cord blood use and banking options.

References

Navarrete C, Contreras M. Cord blood banking: a historical perspective. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(2):236–45.

Gluckman E. Milestones in umbilical cord blood transplantation. Blood Rev. 2011;25:255–9.

Ballen KK, Verter F, Kurtzberg J. Umbilical cord blood donation: public or private? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015:1–8.

Yoder MC. Cord blood banking and transplantation: advances and controversies. Pediatrics. 2014;26(2).

Waller-Wise R. Umbilical cord blood: information for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2011;20(1):50–60.

Guilcher G, Fernandez CV, Joffe S. Are hybrid umbilical cord blood banks really the best of both worlds? J Med Ethics. 2013;41:272–5.

Han MX, Craig ME. Research using autologous cord blood - time for a policy change. Med J Aust. 2013;199(4):288–90.

Mayani H. Umbilical cord blood: lessons learned and lingering challenges after more than 20 years of basic and clinical research. Arch Med Res. 2011;42:645–51.

Petrini C. Ethical issues in umbilical cord blood banking: a comparative analysis of documents from national and international institutions. Transfusion. 2013;53:902–10.

Skabla P, McGadney-Douglas B, Hampton J. Educating patients about the value of umbilical cord blood donation. Journal of American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2010;23(11) 33–34, 39–40.

Plant M, Knoppers BM. Umbilical cord blood banking in Canada: socio-ethical and legal issues. Health Law Journal. 2005;13:187–212.

Samuel G, Kerridge IH, O'Brien TA. Umbilical cord blood banking: public good or private benefit? Med J Aust. 2008;188(9):533–5.

Fox NS, Stevens C, Ciubotariu R, Rubinstein P, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA. Umbilical cord blood collection: do patients really understand? J Perinat Med. 2007;35(4):314–21.

Manegold G, Meyer-Monard S, Tichelli A, Granado C, Hosli I, Troeger C. Controversies in hybrid banking: attitudes of Swiss public umbilical cord donors towards private and public banking. Arch Gynecology Obstetrics. 2011;284:99–104.

Perlow JH. Patients' knowledge of umbilical cord blood banking. J Reprod Med. 2006;51(8):642–8.

Kornhaber RA, McLean LM, Baber RJ. Ongoing ethical issues concerning authorship in biomedical journals: an integrative review. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:4837–46.

Whittmore R, Knafi K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53.

Sugarman J, Cogswell B, Olson J. Pregnant Women's Perceptives on umbilical cord blood banking. J Women's Health. 1998;7(6):747–57.

CASP: Making sense of evidence.

Bioinformant Worldwide LLC. Cord blood banking survey 600+ recent and expectant parents; Geography Worldwide. WwwBioInformantcom 2014. 2014:1–51.

Surbrek D, Islebe A, Schonfeld B, Tichelli A, Holgreve W. Umbilical cord blood transplantation: acceptance of umbilical cord blood donation by pregnant patients. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1998;128(18):689–95.

Kim MO, Yoo JS, Park CG, Ahn HM. Knowledge and attitude to cord blood of early postpartum women after donating cord blood or storing cord blood. Korean Journal of Womens Health Nursing. 2009;15(1):13–23.

Dunbar NM. Between the trash can and the freezer: donor education and the fate of cord blood. Transfusion (Philadelphia, Pa). 2011;51:234–6.

Wagner AM. Use of human embryonic stem cells and umbilical cord blood stem cells for research and therapy: a prospective survey among health care professionals and patients in Switzerland stem cell survey in Switzerland. Transfusion (Philadelphia, Pa). 2013;53(11):2681–9.

Parco S, Vascotto F, Visconti P. Public banking of umbilical cord blood or storage in a private bank:testing social and ethical policy in northeastern Italy. Journal of Blood Medicine. 2013;4:23–9.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematics analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Sugarman J, Kurtzberg J, Box TI, Horner RD. Optimization of informed consent for umbilical cord blood banking. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;187(6):1642–6.

Fernandez CV, Gordon K, Van den Hof M, Taweel S, Baylis F. Knowledge and attitudes of pregnant women with regard to collection, testing and banking of cord blood stem cells. CMAJ. 2003:695–8.

Dinc H, Sahin NH. Pregnant Women's knowledge and attitudes about stem cells and cord blood banking. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56(2):250–6.

Palten PE, Dudenhausen JW. A great lack of knowledge regarding umbilical cord blood banking among pregnant women in Berlin, Germany. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(6):651–8.

Rucinski D, Jones R, Reyes B, Tidwell L, Phillips R, Delves D. Exploring opinions and beliefs about cord blood donation among Hispanic and non-Hispanic black women. Transfusion. 2010;50:1057–63.

Salvaterra E, Casati S, Bottardi S, Brizzolara A, Calistri D, Cofano R, Folliero E, Lalatta F, Maffioletti C, Negri M, et al. An analysis of decision making in cord blood donation through a participatory approach. Transfus Apher Sci. 2010;42(3):299–305.

Suen SSH, Lao TT, Chan OK, et al. Maternal understanding of commercial cord blood storage for their offspring - a survey among pregnant women in Hong Kong. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(9):1005–9.

Katz G, Mills A, Garcia J, Hooper K, McGuckin C, Platz A, Rebulla P, Salvaterra E, Schmidt AH, Torrabadella M. Banking cord blood stem cells: attitudes and knowledge of pregnant women in five European countries. Transfusion. 2011;51:578–86.

Shin S, Yoon JH, Lee HR, Kim BJ, Roh EY. Perspectives of potential donors on cord blood and cord blood crypreservation: a survey of highly educated, pregnant Korean women receiving active prenatal care. Transfusion. 2011;51:277–82.

Screnci M, Murgi E, Pirre G, Valente E, Gesuiti P, Corona F, Girelli G. Donating umbilical cord blood to a public bank or storing it in a private bank: knowledge and preference of blood donors and of pregnant women. Blood Transfus. 2012;10:331–7.

Padmavathi P. Effects of Structured Teaching Programme regarding Stem Cells and Umbilical Cord Blood Banking on Knowledge among Antenatal Mothers. Nurs J India. 2013;CIV(4):30–2.

Meissner-Roloff MP, M. Establishing a public umbilical cord blood stem cell Bank for South Africa: an enquiry into public acceptability. Stem Cell Review and Reproduction. 2013;9:752–63.

Alexander NI, Olayinka AO, Terrumun S, Felix EA. Umbilical cord blood donation and banking: awareness among pregnant women in Makurdi, Nigeria. Journal of dental and Medical Sciences. 2014;13(1):16–9.

Jordens CF, Kerridge IH, Stewart CL, O'Brien TA, Samuel G, Porter M, O'Connor MA, Nassar N. Knowledge, beliefs, and decisions of pregnant Australian women concerning donation and storage of umbilical cord blood: a population-based survey. Birth. 2014;41(4):360–6.

Karagiorgou LZ, Pantazopoulou MP, Mainas NC, Beloukas AI, Kriebardis AG. Knowledge about umbilical cord blood banking and Greek citizens. Blood Transfus. 2014:353–60.

Danzer E, Holzgreve W, Troeger C, Kostka U, Steimann S, Bitzer J, Gratwohl A, Tichelli A, Seelmann K, Surbek DV. Attitudes of Swiss mothers towards unrelated umbilical cord blood banking 6 months after donation. Transfusion. 2003;43:604–8.

Vijayalakshmi S: Knowledge on collection and storage of cord blood banking. Singhad e Journal of Nursing 2013, 111(1):14–17.

Kim M, Han S, Shin M. Influencing factors on the cord blood donation of post-partum women. Nursing and Health Science. 2015;17:269–75.

Matsumoto M, Dajani R, Khader Y, Matthews K. Assessing women's knowledge and attitudes towards cord blood banking: policy and ethical implications for Jordan. Transfusion. 2016;56:2052–60.

Matijevic R, Erjavec K. Knowledge and attitudes among pregnant women and maternity staff about umbilical cord blood banking. Transfus Med. 2016;26(6):462–6.

Jordens CF, O'Connor MA, Kerridge IH, Stewart CL, Cameron A, Keown D, Lawrence RJ, McGarrity A, Abdulaziz S, Tobin B. Religious perspectives on umbilical cord blood banking. J Law Med. 2012;19:497–511.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care: National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. In., vol. September. Sydney: Commonwealth of Australia; 2012.

Cook Carter M, Correy M, Delbanco S, Foster CS, Friedland R, Gabel R, Gipson T, Rima Jolivet R, Main E, Sakala C, et al. 2020 vision for a high-quality, high-value maternity care system. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20:7–17.

Crawford M, Rutter D, Manley C, Weaver TKB, Fulop N, Tyrer P. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. British Medical Journal. 2002;325.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable to this integrative review of published studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceptualized the review and selected the review methodology. LP conducted the literature search, identified articles for inclusion and analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript. JY, DM and LK checked the search strategy, reviewed included articles, and contributed to the contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. All named authors contributed sections of the text and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Appraisal of Quantitative studies by study design using CASP tools. CASP tool assessments of Quantitative studies listed chronologically. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 2:

Appraisal of Qualitative studies by study design using CASP tools. CASP tool assessments of Qualitative studies listed chronologically. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Peberdy, L., Young, J., Massey, D. et al. Parents’ knowledge, awareness and attitudes of cord blood donation and banking options: an integrative review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 395 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2024-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2024-6