Abstract

Background

Maternal and perinatal mortality in Mozambique were declining at a slow pace, despite progress in coverage of institutional childbirth. Implementation of quality emergency obstetric care including vacuum extraction remained inadequate. In 2015–2017, Tete Province achieved remarkable progress in improving emergency obstetric care and reversing the underutilisation of vacuum extraction, with encouraging results for maternal and perinatal outcomes, despite severe resource constraints. This paper presents the experience of Tete Province, generating a rich, contextualised understanding, which might provide generalizable insights and lessons.

Methods

This qualitative study design is used to present Tete’s experience in improving emergency obstetric care and reversing the underutilisation of vacuum extraction, drawing on principles from implementation science and applying a systems thinking approach. Sources include routine data, documents, social media messages, and the lived experience of the authors, all intimately involved in the implementation process during 2014–2017. Iterative learning and analysis, involving all authors, led to the final interpretations.

Results

Within a context of severe resource constraints, Tete applied 4 interventions (training, accreditation, audit, monitoring and evaluation with feedback) to improve the implementation of emergency obstetric care. Considerable progress was achieved in vacuum extraction and other signal functions of emergency obstetric care and in the decision-making process for caesarean sections, contributing to important reductions in the provincial institutional maternal mortality and stillbirth rates. Facilitating factors include attributes of the vacuum extraction itself, of the structural and organisational environments in which it was introduced, of the people involved in implementation, and of the process through which the implementation was rolled-out.

Conclusions

The lessons from implementation science and systems thinking can contribute to surprising results in the improvement of emergency obstetric care including the use of vacuum extraction, even in a severely resource-constrained setting. The creation of conditions for real change, with empowerment of the staff and managers at the front-line of day-to-day practice in Tete may inspire others in similar conditions and circumstances. The underutilisation of vacuum extraction in middle- and low-income countries is indeed a missed opportunity. Its reversion is possible and provides a good chance to make considerable difference in maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mozambique is one of many countries which have not managed to reduce their maternal mortality fast enough to achieve Millennium Development Goal 5 (reduction of maternal mortality ratio by three quarters between 1990 and 2015), despite increasing access to, and utilisation of, institutional childbirth. Similarly, the country’s progress in the reduction of under-five mortality has not been fast enough to achieve Millennium Development Goal 4 (reduction of under-five mortality rate by two thirds between 1990 and 2015), mostly because neonatal mortality has not reduced much [1, 2]. It has been suggested that an adequate coverage of skilled birth attendants is not sufficient to improve maternal and perinatal outcomes, but that good coverage and quality of emergency obstetric care are additional prerequisites [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Of the essential emergency obstetric interventions, vacuum extraction is most underutilised in low and middle income countries [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Instead, there is often an excessive dependence upon caesarean section [16], despite its limited access in many low-income countries, such as Mozambique. Aiming to accelerate progress within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals, improved access and quality of maternity care form an important objective in the current strategic plans of the Mozambican Government and its Ministry of Health.

Mozambique has had clear recommendations for emergency obstetric care for many years, based on WHO recommended practices. These include nine signal interventions: administration of antibiotics, oxytocin, magnesium sulphate and blood transfusion as well as performance of caesarean section, vacuum extraction, manual removal of placenta, neonatal resuscitation, and intra-uterine aspiration [17, 18]. In addition, the country implements a successful task-sharing strategy for the provision of emergency obstetric care and midwives are trained in the use of vacuum extraction [19]. However, widespread implementation of all essential emergency obstetric interventions remains a challenge, and both underuse and overuse of caesarean sections has been identified [20]. As elsewhere in Mozambique and similar countries, Tete has been trying to improve obstetric emergency care for years, especially care for prolonged labour, which was locally identified as an important cause of institutional maternal mortality and stillbirth [21]. Despite these efforts, according to routine data in the last quarter of 2014, only 8 of Tete’s 106 health facilities performed all signal interventions for basic or comprehensive emergency obstetric care, indicating very limited access to emergency obstetric care for the 2.5 million inhabitants living dispersed in the mostly rural province. Vacuum extraction was the least performed signal function, few direct obstetric complications were reported and case fatality rates for each of the five direct obstetric complications were above 1%.

In 2015–2017, after implementation of a series of mostly non-clinical interventions, Tete Province managed to achieve remarkable progress in improving emergency obstetric care and reversing the underutilisation of vacuum extraction, with encouraging results for maternal and perinatal outcomes, despite severe resource constraints. Few such successful experiences in low-income countries, especially from Sub-Saharan Africa, have been documented, rarely addressing the underutilisation of vacuum extraction [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. This paper aims to comprehensively present the experience of Tete Province to generate a rich, contextualised understanding, providing generalizable insights and lessons for replication.

Methods

This paper uses a qualitative study design to present Tete’s experience with improving emergency obstetric care and reversing underutilisation of vacuum extraction, drawing on principles from implementation science and applying a systems-thinking approach. Implementation science studies the phenomena related to implementation of evidence-based health innovations in complex real-life health-related settings [29, 30]. Adam & de Savigny (2012) described systems thinking as a way of thinking in approaching problems and designing solutions, which frames problems in terms of patterns of behaviour over time and places the responsibility for this behaviour on the system’s internal actors. For a deeper understanding of the actors’ behaviour it is considered crucial to understand their relationship context, while concentrating on causality, understanding how the behaviour is generated and maintained, viewing causality as an on-going process, with effects feeding back to influence causes and the causes affecting each other [31].

This approach enables not only a description of implemented interventions and achieved results in Tete Province, but more importantly, of how these interventions and results were implemented, achieved and maintained, aiming to provide useful clues for replication elsewhere. The authors were all intimately involved in this experience and its evaluation during their day-to-day work before, during and after 2015–2016, at several levels and with different perspectives, including health system and program management (province, district, facility), medical-technical clinical care, and midwifery. Their combined empirical knowledge ensures a profound understanding of the implementation process, achieved results, and the context in which these occurred. In addition, the study draws on routine data from the provincial health information system, routine progress reports from the provincial health sector, reports on quarterly accreditation in emergency obstetric care, minutes from meetings of the provincial committee for maternal and neonatal death reviews and clinical audits. It also used general non-identifiable information related to emergency obstetric care extracted from the routine managerial communications within the provincial health sector via pre-existing WhatsApp Messenger groups (an instant messaging service for smartphones from WhatsApp Inc., wholly owned by Facebook) between the Provincial Health Directorate and its district health directors, district medical officers, and other relevant managers. Emerging interpretations were discussed and agreed between the authors, as well as consolidated with a wider audience of district managers and health care professionals in the province. The use of existing data for this study from all sources mentioned above has been authorised by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the Zambeze University in Tete.

Results

Context

Tete province is situated in the central region of Mozambique in south-east Sub-Saharan Africa, one of the least developed countries in the world [32]. The province has a surface area of 100,724 km2 subdivided in 15 districts, a population density of around 25 inhabitants per km2 and a largely underdeveloped transport infrastructure. In recent years Tete has experienced a mineral resources boom, resulting in important socio-economic changes and considerable population growth due to national and international immigration. Despite this, the local economy is still mostly based in subsistence agriculture and poverty levels and inequality are high [33]. Literacy levels are low, especially among women, and access to safe water and sanitation or improved housing limited [34]. The epidemiological profile of the province identifies a multiple burden of diseases, with persisting high levels of malaria, diarrheal diseases, HIV/AIDS and other infections, frequent occurrence of health problems related to reproduction and emerging problems of non-communicable diseases and trauma [35]. A description of the provincial health sector is presented in Table 1.

The Mozambican public health sector is financed by the government. In 2014, it was allocated MT 19.1 billion (USD $635.8 million), 7.9% of the total state budget, equivalent to approximately USD $42 per person, far below the SADC average of USD $266 [36]. However, the sector also receives important financial contributions (estimated at an additional 25%) from a multitude of development partners, and is still considered donor-dependent [36]. Tete provincial health sector receives considerable support from bilateral and multilateral donors, and from national and international non-governmental organisations. An important part of this support is directed at HIV/AIDS (largely funded by the Government of the United States of America), while another part focusses on health system strengthening to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights, within which attention has been directed at the improvement of emergency obstetric care (largely funded by the Government of Denmark). In Mozambique, maternity care is free of charge at point of care, as are most other health services for vulnerable population groups.

Interventions

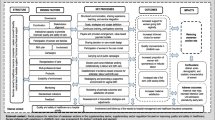

Improvement of maternal and perinatal outcomes had been considered a priority in Tete province for years, following the lead of the Mozambican Ministry of Health. Till 2014 most efforts were directed at promotion of institutional childbirth (through expansion and refurbishment of maternity services and health education) and of modern contraception (through health education and the introduction of new methods of long duration, including implants), with considerable success: institutional childbirth coverage increased from around 50% in 2010 to over 66% in 2014, and the number of couple-years protected per 100 women of reproductive age increased from close to 13 in 2011 to over 32 in 2014. Despite this progress, the provincial institutional maternal mortality rate and stillbirth rate remained high at 100–150 per 100,000 births and around 18 per 1000 newborns, respectively. Provincial managers recognised that coverage and quality of maternity care including emergency obstetric care was insufficient and required interventions. In Mozambique, vacuum extraction tended to be considered as a rather risky practice with many potential dangers for mother and child, and was practiced in only a few health facilities. The practice of craniotomy (perforation of the head of a dead foetus to evacuate its content followed by extraction of the foetus) was even less known about, and considered potentially culturally unacceptable. Despite this, Tete’s provincial health management team authorised implementation of four complementary interventions to address the situation from March 2015 onwards: 1) one-week training of a provincial pilot team on the management of prolonged labour, including vacuum extraction and craniotomy, developed and facilitated by a professor considered an expert on obstetric care in low-income countries both internationally and in Mozambique; 2) strengthening of the quarterly emergency obstetric care accreditation process; 3) monthly audit of clinical files of all cases of caesarean section in the provincial hospital (a large majority of all caesarean sections in the province) with specific feedback to clinicians involved, copied to relevant provincial managers; and 4) strict monitoring and evaluation of routine data from all maternities, with specific feedback to district health directors and doctors, copied to all and to relevant provincial managers. These four non-clinical instruments (training, monitoring and evaluation, audit and constructive feedback) have been shown effective in changing behaviour of health professionals [23, 37,38,39,40,41,42]. They are presented in more detail in Table 2.

The focus on vacuum extraction was chosen because it is a relatively safe intervention even in inexperienced hands, with ample scientific evidence for its potential to reduce maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality [5, 10, 13, 28]. Craniotomy and other destructive procedures have also long been considered safer than caesarean section in cases of prolonged and infected labour with intra-uterine foetal death [43, 44]. As no specific budget had been allocated to these interventions during the annual planning process for 2015, all interventions occurred within routine activities and without additional financial incentives, except the training, which was funded through the program for health system strengthening to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Progress achieved

The number of health facilities quarterly accredited in basic or comprehensive emergency obstetric care is presented in Fig. 1. After mid 2015 vacuum extraction was no longer the least performed signal intervention, replaced in that position by intra-uterine aspiration, administration of antibiotics or of magnesium sulphate. The performance of all signal interventions improved, as any one was performed each quarter on average by 25 health facilities in early 2015, increasing to 44 at the end of 2016, and to 47 in the first quarter of 2017, after which it reduced somewhat and stabilised around 42 during the remainder of that year. As a result, considerable changes were observed in the coverage of emergency obstetric care at provincial level, although some progress was lost during 2017 (Table 3). The use of vacuum extraction increased considerably from 2014 to 2016, and stabilised during 2017, while the percentage of institutional births assisted by caesarean section reduced (Table 4). Not only the absolute number and the percentage of institutional births assisted with vacuum extraction increased dramatically, but also the number and proportion of health facilities which performed at least one vacuum extraction during each three-month period. The percentage of institutional births assisted by either vacuum extraction or caesarean section therefore increased considerably, especially in district and peripheral health facilities without surgical capacity.

The monthly audit of the clinical files of all caesarean sections in the provincial hospital revealed that, initially, surgery occurred often ‘too little, too late’ but also ‘too much, too soon’ [45]. Similar audit findings have been described for various hospitals in Tanzania [46,47,48]. After interventions started in April 2015 changes occurred gradually, accelerating during 2016, as shown through selected indicators in Table 5. The observed reduction of births attended in the hospital appeared to be related to the inauguration of an additional Mother and Child Health (MCH) nurse led maternity close by and to an increased use of peripheral maternities in case of uncomplicated births. Craniotomy and other destructive procedures were introduced as a substitute to caesarean sections in cases of intra-uterine foetal death, without any objections of patients or their families after appropriate explanations with informed consent. The persistently high intra-hospital caesarean section rate was probably related to the changing case-mix of relatively more severely complicated births and referrals, as also suggested by the increasing concentration of maternal deaths in the provincial hospital. It appeared that the shift in indications for caesarean section had reduced at least part of those ‘too little, too late’ as well as of those ‘too much, too soon’, without compromising maternal and foetal outcomes.

At provincial level, maternal and perinatal outcomes after institutional childbirth improved between 2014 and 2017. Institutional maternal mortality per 100,000 births and stillbirths per 1000 newborns reduced considerably (Fig. 2). Case fatality rates of direct obstetric complications reduced from 2.2% in 2014 to 0.4% at the end of 2016 and 0.8% during 2017. The reduction in case fatality rates was similar in each direct complication, prolonged labour, obstetric haemorrhage, (pre-) eclampsia, and sepsis; in 2016, all achieved rates below 1% due to a combination of fewer maternal deaths and more frequent diagnosis and treatment of cases with complications. However, during 2017 the case fatality rates for (pre-) eclampsia and sepsis rose again to well above 1%. The monthly institutional stillbirth rate was inversely associated with the percentage of vacuum extractions among institutional births, but positively associated with the percentage of caesarean sections (Figs. 3 and 4).

Mozambique does not collect reliable routine data on neonatal deaths. Yearly admissions due to asphyxia to the neonatal intensive care unit in the provincial hospital fluctuated around 400–450 between 2014 and 2016, and the case fatality rate ranged from 21% in 2014 to 16% in 2015 and 29% in 2016. Nevertheless, the impression of the provincial paediatrician as well as of provincial programme managers is that perinatal outcomes in general, both stillbirth and neonatal death, had improved in recent years. Taken together with the increasing coverage of institutional births, it is likely that the improvements in institutional maternal and perinatal outcomes extend to population level.

Enabling factors for implementation

It has been well documented that many interventions to improve health have been scientifically proven effective, but are not generally applied in daily practice, as was the case with Mozambique’s obstetric care guidelines [49]. The lack of implementation may be attributed to barriers at health system level, such as insufficient funding or human resources, or at health facility level, such as a lack of equipment or of capable midwives, a lack of leadership to ensure quality of clinical care or inadequate teamwork [50,51,52]. Rather than documenting barriers for implementation, this study chooses to present enabling factors, organised within an implementation science perspective, in factors related to a) the innovation itself, b) the structural and organisational environments in which the innovation is introduced, c) the people involved in the implementation (managers, staff, patients), and d) the process through which the implementation was rolled-out (adapted from Damschroder et al., 2009 and Chaudoir et al., 2013 [29, 30]).

-

a)

The innovation itself, vacuum extraction

An important key to success is the choice of the correct intervention for the problem which needs solving. In this case, the main problem to be addressed was the inadequate management of prolonged labour as principal cause of institutional maternal death and stillbirth. Vacuum extraction was re-introduced within a generally improved management of labour, including completion of the partogram and its use for timely decision-making, conservative interventions such as artificial rupture of membranes and augmentation with oxytocin intravenously, with caesarean section as last recourse. This course of action is in accordance with national and international guidelines, and was recommended by a senior expert with longstanding experience in Mozambique and good connections with several high-level personnel of the Ministry of Health, which made the advice unreservedly acceptable to Tete’s health personnel and managers.

Other positive aspects of vacuum extraction are directly related to the instrument. It is safe even in less-experienced hands, it offers the opportunity to regularly practice in non-urgent situations, for example in tired nulliparous women with a slight delay in the second stage of labour. It is a procedure of little complexity, which can be guided by few simple criteria and rules. The components of the instrument may be put together in a variety of combinations, which makes functional availability at peripheral level more likely. The positive effect of its successful use is immediate and rewarding for the practitioner (and the patient). This offers a more favourable option in the periphery compared with referral and summoning an ambulance or facing the possibility of an asphyxiated newborn or intra-partum stillbirth. The new handheld model vacuum extractor, received from national level, is small and easy to use, which encouraged its utilisation. Even after the model tended to break down with repeated use, MCH nurses were already convinced that vacuum extraction was an intervention they could perform and was beneficial to them and their patients. This meant they would look for, assemble, and use alternative equipment, which was already available to some extent in the province. Many additional resources were thus not required: checking inventories and subsequent redistribution was largely sufficient. Some experience with vacuum extraction was already present among the MCH nurses, which facilitated in-service training within existing teams. Similarly, some experience with augmentation with oxytocin or misoprostol, vacuum extraction, craniotomy and other destructive procedures, existed among obstetricians in the provincial hospital.

-

b)

The structural and organisational environments in which the innovation was introduced

The Mozambican government and health sector are structures with a strong hierarchy, which consider the reduction of maternal mortality an important priority. Every month, data on maternal deaths must be presented directly from the provincial health directorate to the provincial governor and to the minister of health, which creates considerable pressure to find ways to success. This pressure is then translated down the chain of command, via province and districts to health facilities and individual staff, creating an environment where the reduction of maternal deaths must be on everybody’s agenda. It also sets the stage for a certain competition, for peer pressure between staff, health facilities, districts, and even provinces, to find answers and produce positive results, in the expectation to be recognised and rewarded for them. In a similar fashion, this hierarchical pressure also stimulated Tete’s provincial hospital to try harder to prove its status as tertiary referral hospital with a ‘model maternity’, especially after peripheral health facilities took the lead in improving emergency obstetric care and vacuum extraction.

Based on local research and evaluations, a common understanding had been created within the provincial health directorate on the main contributing factors towards the lack of progress in maternal and perinatal mortality, through which ‘inconvenient truths’ such as poor quality of care within health facilities could be assumed and subsequently addressed. The concurrent programme aimed at health system strengthening focussed on results-based management with evidence-based decision-making, using a ‘complex adaptive systems’ perspective. This led to improvements in health system management, governance, financial management, logistics and transport, human resources management and monitoring and evaluation throughout the provincial health sector. The process involved attention for stronger collaboration, promotion of transformational leadership and iterative learning. Taken together, this permitted the emergence of ‘champions of vacuum extraction’ at peripheral health facilities, whose positive experiences and good initial results aided in a gradually expanding practice of vacuum extraction at provincial, district and health facility level.

-

c)

The people involved in the implementation

Staff: Many MCH nurses were afraid to perform a vacuum extraction, worried about possible damage to mother or child and of repercussions in case of failure to save the baby. Once the process of vacuum extraction and its components were demystified through simple rules and multiple possible assemblies, and once regular performance of vacuum extraction was presented as a routine professional practice of any competent MCH nurse, more staff were gradually willing to try out the procedure in practice. Any attempt to perform vacuum extraction was always praised, even when unsuccessful, because trying and failing was considered better than not trying at all. Many MCH nurses discovered quickly that vacuum extraction is not a difficult procedure, that it is largely safe for mother and child and that it forms a powerful tool for any MCH nurse to resolve difficulties in the second stage of labour without need to obtain outside assistance, avoiding unnecessary referrals or caesarean sections. In peripheral health facilities, MCH nurses realised that it was often easier for them to perform vacuum extraction than to convince the patient and her family that referral was necessary and to subsequently arrange an ambulance. The following quote from a group of MCH nurses in a provincial meeting on maternal and perinatal mortality summarises this process of empowerment:

“We knew that a vacuum extraction is an instrumental childbirth which might reduce perinatal mortality and also reduce the anxiety of the mother in a situation of prolonged labour. But in the beginning, we were afraid and apprehensive. We needed individual change, to gain courage and start performing vacuum extractions when we as MCH nurses considered it necessary to save a foetus in danger of perinatal mortality. Now, when we do a vacuum extraction, it means a victory and an achievement to us.”

In the provincial hospital, staff gradually gained the confidence to promote vaginal births rather than quickly deciding on a caesarean section. The understanding emerged that caesarean section is not always the best solution, that a vaginal birth may be safer for mother and baby, and that caesarean section might be best seen as a last resort if all else fails. Better collaboration within the multidisciplinary team, with clearer divisions of roles, more dialogue and second opinions aided in this process.

Patients: Although direct contributions from patients were not available, staff reports suggested that assistance with vacuum extraction during prolonged labour was gratefully received by patients, especially when it saved the baby and avoided referral for caesarean section in a far-away hospital. For socio-cultural reasons, vaginal births are traditionally better accepted than caesarean sections among Tete’s population. Referral to a health facility with surgical capacity is not popular, due to difficult travel, return transport costs for the patient and her family, fear of surgical intervention, and the unfortunate fact that often the baby cannot be saved even through surgery due to unavoidable delays related to long distances and poor transport infrastructure. Consequently, many women in Tete’s rural communities know sad histories of acquaintances or family members who experienced difficulties when giving birth, were referred, had a caesarean section but lost their baby and never got pregnant again. Vacuum extraction appears thus as a potentially acceptable tool to promote vaginal birth resulting in a live, healthy mother and baby at peripheral health facilities.

-

d)

The process through which implementation was rolled-out

While a common understanding of the problem of prolonged labour and its possible solutions existed in the province, planning of the four interventions was very limited. Only the training was formally planned, the other interventions were suggested during the training or were included spontaneously shortly afterwards. The roll-out of the innovation did not follow the usual process in the Mozambican health system, consisting in widespread formal training of all staff involved with elaborate written guidelines and protocols. Rather, the implementation process in Tete was flexible and responsive to changes and resistance, relying mostly on personal initiatives of MCH nurses and other maternity staff, guided by few simple rules and criteria within their day-to-day routines, supervised through existing hierarchies by district medical officers and health directors. By largely avoiding classroom teaching, the impression that vacuum extraction is a difficult procedure which must be formally learned was avoided. This also prevented passive resistance from MCH nurses who had not benefitted from formal training and its accompanying per diem, which tends to be widespread in Mozambique [53].

Most encouragement was directed towards those maternities attending the largest numbers of institutional childbirths, ensuring enough cases to permit regular practice to gain experience and develop skills. Improved practices in these maternities also ensured an impact on a considerable number of childbirths, enough to provoke an impact at provincial level. Early positive results stimulated MCH nurses and district doctors to continue and expand the practice, creating a snowball effect, increasing practice and increasing benefits for maternal and perinatal outcomes, resulting in the creation of a virtuous circle.

Initial results were presented to the provincial government and the Ministry of Health, which created a pressure to move forward, as permitting a resurgence of maternal and perinatal mortality after its reduction was shown possible would mean a severe loss of face for Tete’s provincial managers. The practice of vacuum extraction was therefore included in the list of priority activities on which monthly feedback was required via phone message from districts directly to the provincial chief medical officer. Pressure for accountability on results via email, WhatsApp, phone messages, reports, meetings, etc. was strong and mostly public among provincial and district staff, as were prizes and praise for those performing well. As such, peer pressure aided in the establishment of a new cultural norm in which vacuum extraction is now considered a normal part of day-to-day practices of any competent MCH nurse or district doctor. However, this peer pressure was interrupted in 2017 due to staff changes at provincial level affecting the chief medical officer, chief public health officer, MCH manager and locally-based international technical advisor, which explains the partial relapse noted during 2017, especially in the implementation of all signal interventions as required for accreditation. Determined to maintain previous advances, steps to resume the regular accreditation and feedback system have been taken by relevant managers of the Provincial Health Directorate at the start of 2018.

Discussion

This experience of Tete Province, Mozambique, with improvement of emergency obstetric care including vacuum extraction, shows that it is possible to make progress in maternal and perinatal mortality, even in a severely resource-constrained setting and without a large budget for interventions. The role of skilled and empowered MCH nurses and midwives appears as a crucial element, as described in other publications [54,55,56]. Once they are convinced of the benefits of vacuum extraction for themselves and for their patients, and once they are permitted and enabled to use this instrument as trusted professionals, they will take the chance with both hands and deliver results for mother and child. This study demonstrates Freedman’s statement in The Lancet: “The true engine of change in maternal health will not be the formal clinical guidelines, polished training curricula, model laws, or patient rights charters we produce. The engine will be the determination of people at the front-lines of health systems—patients, providers, and managers—to find or take the power to transform their own lived reality” [57]. Such transformation can be achieved with existing, proven interventions, when implemented with careful attention to the lessons from implementation science and systems thinking. Context and process of implementation are of crucial importance for success, although these tend to receive little attention in more traditionally designed programmes. The construction of a common goal through local learning requires extensive pre-intervention groundwork, sometimes over years, to ensure that a truly common understanding may be reached: the conviction that a problem exists which requires evidence-based solutions and that such solutions are within reach, despite all existing constraints. Promoting behaviour change in overworked health staff and managers facing many competing priorities requires a flexible approach, as it is impossible for top-down prescriptions to foresee and address all complexities of their day-to-day practices and experiences. Simple rules and appropriate incentives stimulate innovation, while dictated commands and attempts at control stifle local initiative and personal development. Rather than attempting to engineer change, one can create and then nurture the conditions for change to emerge [31, 58, 59].

The underutilisation of vacuum extraction has been repeatedly pointed out as a missed opportunity to improve emergency obstetric care in middle and low-income countries (most recently by Bailey et al., 2017 [15]), but interventions aiming to reverse this are still rare. Nolens et al., 2016 [28] described a successful intervention in the national referral hospital of Uganda, where vacuum extractions increased while caesarean sections remained stable and an association with improved maternal and perinatal outcome was strongly suggested. Others tended to present a more general focus on improvement of emergency obstetric care without specific mention of vacuum extraction [22,23,24,25,26,27, 60, 61]. Often an increase of caesarean section is described as a positive effect in such studies, but in view of Tete’s experiences and the emergence of many caesarean sections performed “too much, too soon”, this might need refinement in future work to separate unavoidable caesarean sections from those with less firm indications. In addition, future studies might include attention to potential cost-savings of using vacuum extraction instead of caesarean section in resource-constraint health systems, which remained outside the scope of this study.

This study depended on routine data and lived experiences during day-to-day work, without any formal data collection process for scientific purposes. This implies necessarily a concern for data quality, although it is unlikely that inadequate quality would be responsible for positive changes in such a wide range of obstetric care indicators. Possibly data quality may have improved with the increased attention for maternity monthly reports. Internal routine data quality assessments in 2015 and 2016 based on a methodology developed by World Health Organisation showed that completeness, internal and external validity of institutional childbirth data per health facility were sufficient to make them fit for purpose. The analysis of lived experiences without a formal note-taking system presents the chance of recall mistakes. This weakness was partly addressed using routinely prepared documentation (WhatsApp messages, minutes of meetings, etc.) and through dialogue and verification of findings and interpretations with all actors involved. The implementation framework ensured in-depth analysis of all possible relevant aspects, which diminished the chance that some vital component might have been overlooked.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to include direct voices and perspectives from patients and further research will be required to confirm or disprove the views received indirectly via health staff. Despite these limitations, given the importance and relevance of the topic, this study still presents lessons and insights useful for future efforts aimed at improvement of emergency obstetric care and re-introduction of vacuum extraction in similar areas and countries.

Conclusions

The lessons from implementation science and systems thinking can contribute to surprising results in the improvement of emergency obstetric care including use of vacuum extraction, even in a severely resource-constrained setting and without a large budget for interventions. The creation of conditions for real change, with empowerment of the staff and managers at the front-line of day-to-day practice in emergency obstetric care in Tete province should serve as an inspiration for others in similar conditions and circumstances. The underutilisation of vacuum extraction in middle- and low-income countries is indeed a missed opportunity. Its reversion is possible even in resource-constrained settings and provides a good chance to make considerable difference to maternal and perinatal outcomes.

References

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, African Union, African Development Bank and United Nations Development Programme. MDG Report 2015: Assessing Progress in Africa toward the Millennium Development Goals. 2015. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/mdg/mdg-reports/africa-collection.html

United Nations Children’s Fund. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality, Report 2014. Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York: United Nations Children's Fund; 2014.

World Health Organization. Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Geneva: WHO/RHR/ 00.7; 2003.

World Health Organization. Integrated management of pregnancy and childbirth. WHO recommended interventions for improving maternal and newborn health. Geneva: WHO/MPF/07.05; 2007.

Hofmeyr GJ, Haws RA, Bergström S, Lee ACC, Okong P, Darmstadt GL, Mullany LC, Oo EKS, Lawn JE. Obstetric care in low-resource settings: what, who, and how to overcome challenges to scale up? Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;107:S21–45.

Ki-Moon B. Global strategy for women’s and children’s health. New York: United Nations; 2010.

Yakoob MY, Ali MA, Ali MU, Imdad A, Lawn JE, Van Den Broek N, Bhutta ZA. The effect of providing skilled birth attendance and emergency obstetric care in preventing stillbirths. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 3):S7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S7

Graham WJ, McCaw-Binns A, Munjanja S. Translating coverage gains into health gains for all women and children: the quality care opportunity. PLoS Med. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001368.

Campbell OMR, Calvert C, Testa A, Strehlow M, Benova L, Keyes E, Donnay F, Macleod D, Gabrysch S, Rong L, Ronsmans C, Sadruddin S, Koblinsky M, Bailey P. The scale, scope, coverage, and capability of childbirth care. Lancet. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31528-8

Bailey PE. The disappearing art of instrumental delivery: time to reverse the trend. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2005;91:89–96.

Fauveau V. Is vacuum extraction still known, taught and practiced? A worldwide KAP survey. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006;94:185–9.

Ameh C, Weeks A. The role of instrumental vaginal delivery in low resource settings. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116(Suppl. 1):22–5.

Tsu V, Coffey P. New and underutilised technologies to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity: what progress have we made since Bellagio 2003? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116:247–56.

Adegoke A, Utz B, Msuya SE, van den Broek N. Skilled birth attendants: who is who? A descriptive study of definitions and roles from nine sub Saharan African countries. PLoS One. 2012; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040220.

Bailey PE, Roosmalen J, Mola G, Evans C, Bernis L, Dao B. Assisted vaginal delivery in low and middle income countries: an overview. BJOG. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14477.

Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148343.

Jamisse L, Songane F, Libombo A, Bique C, Faúndes A. Reducing maternal mortality in Mozambique: challenges, failures, successes and lessons learned. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;85:203–12.

Ministery of Health (MISAU). Technical Manual on Assistance during childbirth, to newborns, and for the main obstetric and neonatal complications. Maputo: Mozambican Ministry of Health; 2011.

Schneeberger C, Mathai M. Emergency obstetric care: making the impossible possible through task shifting. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(Suppl 1):S6–9.

Long Q, Kempas T, Madede T, Klemetti R, Hemminki E. Caesarean section rates in Mozambique. MC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0686-x.

Geelhoed D, Stokx J, Mariano X, Mosse Lázaro C, Roelens K. Risk factors for stillbirths in Tete, Mozambique. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;130:148–52.

Santos C, Diante D Jr, Baptista A, Matediane E, Bique C, Bailey P. Improving emergency obstetric care in Mozambique: the story of Sofala. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006;94:190–201.

Kayongo M, Rubardt M, Butera J, Abdullah M, Mboninyibuka D, Madili M. Making EmOC a reality—CARE’s experiences in areas of high maternal mortality in Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006;92:308–19.

Nyamtema AS, Pemba SK, Mbaruku G, Rutasha FD, Jos van Roosmalen J. Tanzanian lessons in using non-physician clinicians to scale up comprehensive emergency obstetric care in remote and rural areas. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9(28) https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-9-28

Dumont A, Fournier P, Abrahamowicz M, Traoré M, Haddad S, Fraser WD. For the QUARITE research group. Quality of care, risk management, and technology in obstetrics to reduce hospital-based maternal mortality in Senegal and Mali (QUARITE): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382:146–57.

Nyamtema AS, Mwakatundu N, Dominico S, Mohamed H, Pemba S, Rumanyika R, Kairuki C, Kassiga I, Shayo A, Issa O, Nzabuhakwa C, Lyimo C, van Roosmalen J. Enhancing maternal and perinatal health in under-served remote areas in sub-Saharan Africa: a Tanzanian model. PLoS One. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151419.

Mgaya AH, Kidanto HL, Nystrom L, Essén B. Improving standards of Care in Obstructed Labour: a criteria-based audit at a referral Hospital in a low-Resource Setting in Tanzania. PLoS One. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166619.

Nolens B, Lule J, Namiiro F, van Roosmalen J, Byamugisha J. Audit of a program to increase the use of vacuum extraction in Mulago hospital, Uganda. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1052-3.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009; https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CHI. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8(22). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-22

Adam T, de Savigny D. Systems thinking for strengthening health systems in LMICs: need for a paradigm shift. Health Policy Plan. 2012; https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs084.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Mozambique. HDI values and rank changes in the 2016. Explanatory note on 2016 HDR composite indices. Human Development Report 2016. UNDP New York. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf

Ministery of Economy and Finance (MEF). National Development Strategy 2015-2035. Maputo: Mozambican Ministry of Economy and Finance; 2014.

Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI). Country Briefing 2017: Mozambique. 2017, Oxford, UK. www.dataforall.org/dashboard/ophi/index.php/mpi/download_brief_files/MOZ

Loewenson R and Simpson S (Training and Research Support Centre) in co-operation with DPS Tete and Embassy of Denmark. Situational analysis on health equity and social determinants of health, Tete Province, Mozambique. 2015, Tete, Mozambique. http://www.tarsc.org/publications/documents/Tete%20SitAn%20on%20SDHE%20Eng2015.pdf

United Nations Children’s Fund. Budget Brief: Health sector in Mozambique. 2014. Maputo, Mozambique. http://budget.unicef.org.mz/briefs/2014Health2014.pdf.

Chaillet N, Dubé E, Dugas M, Audibert F, Tourigny C, Fraser WD, et al. Evidence-based strategies for implementing guidelines in obstetrics: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1234–45.

van Lonkhuijzen L, Dijkman A, van Roosmalen J, Zeeman G, Scherpbier A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of training in emergency obstetric care in low-resource environments. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02561.x.

Khunpradit S, Tavender E, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Wasiak J, Gruen RL. Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011; https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005528.pub2.

Raven J, Utz B, Roberts D, van den Broek N. The 'Making it Happen' programme in India and Bangladesh. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;118(Suppl. 2):100–3.

Hulton L, Matthews Z, Martin-Hilber A, Adanu R, Ferla C, Getachew A, Makwenda C, Segun B, Yilla M. Using evidence to drive action: a “revolution in accountability” to implement quality care for better maternal and newborn health in Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.07.002.

Nyamtema AS, de Jong AB, Urassa DP, van Roosmalen J. Using audit to enhance quality of maternity care in resource limited countries: lessons learnt from rural Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:94.

Gupta U, Chitra R. Destructive operations still have a place in developing countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1994; https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7292(94)90017-5

Hofmeyr GJ. Obstructed labor: using better technologies to reduce mortality. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;85(Supplement 1):S62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.01.011

Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, Ciapponi A, Colaci D, Comandé D, Diaz V, Geller S, Hanson C, Langer A, Manuelli V, Millar K, Morhason-Bello I, Pileggi Castro C, Nogueira Pileggi V, Robinson N, Skaer M, Souza JP, Vogel JP, Althabe F. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6

Maaløe N, Sorensen B, Onesmo R, Secher N, Bygbjerg I. Prolonged labour as indication for emergency caesarean section: a quality assurance analysis by criterion-based audit at two Tanzanian rural hospitals. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119:605–13.

Mdegela M, Muganyizi P, Pembe A, Simba D, van Roosmalen J. How rational are indications for emergency caesarean section in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania? Tanzan J Health Res. 2012;14(4) https://doi.org/10.4314/thrb.v14j4.1.

Heemelaar S, Nelissen E, Mdoe P, Kidanto H, van Roosmalen J, Stekelenburg J. Criteria-based audit of caesarean section in a referral hospital in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12683.

Green LA, Seifert CM. Translation of research into practice: why we can’t “just do it”. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:541–5.

Ollerhead E, Osrin D. Barriers to and incentives for achieving partograph use in obstetric practice in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(281). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-281

Litorp H, Mgaya A, Mbekenga CK, Kidanto HL, Johnsdotter S, Esse B. Fear, blame and transparency: obstetric caregivers' rationales for high caesarean section rates in a low-resource setting. Soc Sci Med. 2015;143:232–40.

Sharma G, Mathai M, Dickson KE, Weeks A, Hofmeyr GJ, Lavender T, Day LT, Mathews JE, Fawcus S, Simen-Kapeu A, de Bernis L. Quality care during labour and birth: a multi-country analysis of health system bottlenecks and potential solutions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(Suppl 2):S2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-15-S2-S2

Ridde V. Per diems undermine health interventions, systems and research in Africa: burying our heads in the sand. Trop Med Int Health. 2010; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02607.x.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). The State of the World’s Midwifery Report. New York: Delivering Health, Saving Lives; 2011.

Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, Delage Silva DRA, Downe S, Powell Kennedy H, Malata A, McCormick F, Wick L, Declercq E. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60789-3

Chavane L, Dgedge M, Degomme O, Loquiha O, Aerts M, Temmerman M. The magnitude and factors related to facility-based maternal mortality in Mozambique. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2016.1256968.

Freedman L. Implementation and aspiration gaps: whose view counts? Lancet. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31530-6

Paina L, Peters DH. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy Plan. 2012; https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czr054.

Swanson RC, Cattaneo A, Bradley E, Chunharas S, Atun R, Abbas KM, Katsaliaki K, Mustafee N, Meier BM. Best a. Rethinking health systems strengthening: key systems thinking tools and strategies for transformational change. Health Policy Plan. 2012; https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs090.

English M, Nzinga J, Mbindyo P, Ayieko P, Irimu G, Mbaabu L. Explaining the effects of a multifaceted intervention to improve inpatient care in rural Kenyan hospitals – interpretation based on retrospective examination of data from participant observation, quantitative and qualitative studies. Implement Sci. 2011;6:124.

Kumar S, Yadav V, Balasubramaniam S, Jain Y, Joshi CS, Saran K, Sood B. Effectiveness of the WHO SCC on improving adherence to essential practices during childbirth, in resource constrained settings. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1139-x.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Staffan Bergström (MD, PhD), Professor Emeritus of International Health at Karolinska Institutet, for his contributions to the training and the focus on vacuum extraction as useful tool to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality in Tete Province.

Funding

The study did not receive any specific funding.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DG, VdD, MS, OM, MILC, CVM, PIPM and CML were closely involved in the implementation, supervision and follow-up of the interventions during 2015–2017. DG prepared the initial draft of the paper. DG, VdD, MS, OM, MILC, CVM, PIPM and CML read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The use of existing routine data for this publication has been authorized by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the Zambeze University in Tete City, Tete Province, Mozambique (dd. 26 June 2016).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Geelhoed, D., de Deus, V., Sitoe, M. et al. Improving emergency obstetric care and reversing the underutilisation of vacuum extraction: a qualitative study of implementation in Tete Province, Mozambique. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 266 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1901-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1901-3