Abstract

Background

Early treatment with tranexamic acid reduces deaths due to bleeding after post-partum haemorrhage. We report the prevalence of haematological, coagulation and fibrinolytic abnormalities in Nigerian women with postpartum haemorrhage.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of the WOMAN trial to assess laboratory data and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) parameters in 167 women with postpartum haemorrhage treated at University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. We defined hyper-fibrinolysis as EXTEM maximum lysis (ML) > 15% on ROTEM. We defined coagulopathy as EXTEM clot amplitude at 5 min (A5) < 40 mm or prothrombin ratio > 1.5.

Results

Among the study cohort, 53 (40%) women had severe anaemia (haemoglobin< 70 g/L) and 17 (13%) women had severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 50 × 109/L). Thirty-five women (23%) had ROTEM evidence of hyper-fibrinolysis. Based on prothrombin ratio criteria, 16 (12%) had coagulopathy. Based on EXTEM A5 criteria, 49 (34%) had coagulopathy.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that, based on a convenience sample of women from a large teaching hospital in Nigeria, hyper-fibrinolysis may commonly occur in postpartum haemorrhage. Further mechanistic studies are needed to examine hyper-fibrinolysis associated with postpartum haemorrhage. Findings from such studies may optimize treatment approaches for postpartum haemorrhage.

Trial registration

The Woman trial was registered: NCT00872469; ISRCTN76912190 (Registration date: 22/03/2012).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tranexamic acid (TXA) administration reduces death due to bleeding in trauma patients. Among patients treated within 3 h of injury, TXA reduces death due to bleeding by one third [1,2,3]. Early activation of fibrinolysis is common after serious injury and contributes to the coagulation abnormalities seen in bleeding trauma patients [4, 5]. Hypo-perfusion and tissue injury are thought to start the coagulopathy, although we do not understand the molecular pathways [6].

Results from the WOMAN trial, a large randomised trial conducted primarily in low and middle income countries, show that early tranexamic acid use reduces death due to bleeding after postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) [7]. This suggests that fibrinolysis is also an important pathophysiological mechanism in obstetric bleeding. However, whereas increased fibrinolysis is common in trauma, its association with PPH is less well known [8]. We report the prevalence of hyper-fibrinolysis in women with PPH in Nigeria.

Methods

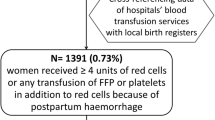

The WOMAN trial was a randomised placebo controlled trial of the effect of tranexamic acid on death, hysterectomy and other surgical interventions in women with clinically diagnosed primary PPH [7]. Although the diagnosis was clinical, we specified that diagnosis of primary PPH could be based on an estimated blood loss of more than 500 mL after vaginal birth or 1000 mL after caesarean section, or any blood loss sufficient to compromise haemodynamic stability. The diagnosis of PPH could also be made using clinical judgement, independent of the volume of blood loss. We have described the methods in detail elsewhere [7]. We examined haematological (full blood count) and haemostatic parameters in a sample of 167 trial participants recruited at University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. A total of 309 women were recruited into the WOMAN trial at University College Hospital. Because of occasional equipment failures and lack of reagents the 167 (54%) women included in the ETAC study were not a consecutive series. Although most of the recruited women delivered at University College Hospital, some patients were transferred from outlying health facilities after they had developed PPH because they required urgent medical support. In these women, blood loss was estimated based on the history and observed blood loss.

After completing consent procedures but before giving the trial treatment (TXA or placebo), we drew approximately 15 mL of venous blood and divided the sample into three vacutainer tubes. We collected one 5 mL sample in a tube containing potassium EDTA for full blood count analysis and two 4.5 mL samples in tubes containing 0.5 mL sodium citrate (0.109 mol/L) for coagulation and rotational thromboelastometry. We used a five-parameter particle counter Sysmex KN analyser (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) for the blood count analysis. Anaemia was defined according to the World Health Organisation definition of anaemia in pregnancy as a haemoglobin below 110 g/L and below 70 g/L for severe anaemia [9].

After centrifuging the blood at 3000 g for 20 min, we measured prothrombin time (PT), normalised prothrombin ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), Clauss fibrinogen and D-dimers using a HumaClot Junior automated coagulation analyser. We measured ROTEM thromboelastometry parameters at 37 °C using two of the four channels (EXTEM, APTEM) of the ROTEM coagulation analyser [TEM®, Munich, Germany]). In EXTEM, coagulation is initiated using a small amount of tissue factor and the development of the clot is expressed in numbers and as a trace. In APTEM, coagulation is initiated in the same way, but the addition of aprotinin or tranexamic acid in the reagent inhibits fibrinolysis in vitro. By comparing the two traces, the extent of fibrinolysis can be assessed. If the sample is hyper-fibrinolytic, the same degree of clot lysis seen in EXTEM is not present in APTEM (Fig. 1). The following ROTEM variables were examined from the EXTEM and APTEM traces (Fig. 2): Clotting time (CT) which corresponds to the time required to trigger the process of coagulation, amplitude of the clot at 5 min and 10 min (CA5 and CA10, respectively), maximum clot firmness (MCF), clot lysis at 30 min and 60 min (LI30 and LI60, respectively), and maximum lysis (ML). We stored the ROTEM reagents at 2–8 °C with temperature monitoring and we used in date reagents.

We conducted quality control (QC) analyses as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Before starting the study, TEM staff trained the Nigerian study team to use the ROTEM machine. We stored the ROTEM data on the machine with a backup after each analysis. We collected, cleaned and analysed the study data at the Clinical Trials Unit of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Fibrinolysis was assessed as the amount of clot lysis on EXTEM (https://www.rotem.de/en/methodology/interpretation/). We defined hyper-fibrinolysis as ML > 15% on ROTEM EXTEM. This definition of hyper-fibrinolysis is provided by the manufacturer and is widely used in research studies [4]. Coagulopathy was defined as an EXTEM A5 < 40 mm or a prothrombin ratio > 1.5. This A5 definition of coagulopathy was based on studies of the use of ROTEM to diagnose acute traumatic coagulopathy in which a A5 < 40 mm predicted the receipt of massive blood transfusion in 73% of patients [10, 11]. Normal ROTEM values for peri-partum Nigerian women have not been studied, so instead we have indicated the normal values from a study of 161 healthy peri-partum Dutch women [12].

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 167 women. One hundred and twenty eight women (77%) gave birth in the hospital, whereas 39 (23%) gave birth in other settings and were admitted after PPH onset. Seventeen (10%) women received colloids during fluid resuscitation for PPH prior to sampling. The estimated mean blood loss at the time of randomisation and blood sampling was 1531 mL. One hundred and eight (65%) women lost more than 1000 mL of blood.

Table 2 shows the full blood count and haemostatic parameters. One hundred and sixteen (88%) women were anaemic (haemoglobin < 110 g/L) and 53 (40%) were severely anaemic (haemoglobin < 70 g/L) at the time of sampling. Thirty eight women (33%) had a microcytic picture (defined as an mean corpuscular volume < 80 fl), although there was no further investigation to discover if this was due to iron deficiency or thalassemia traits or both. Twenty-six women (21%) were lymphopenic (lymphocyte count < 1 × 109/L). Forty-one (32%) women had thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100 × 109/L) and 17 (13%) had severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count< 50 × 109/L).

Thirty five women (23%) had an EXTEM ML > 15%. If defined as an EXTEM A5 < 40 mm, coagulopathy was present in 49 (34%) mothers. If defined as a prothrombin ratio > 1.5, coagulopathy was present in 16 (12%) mothers. Of the women with an EXTEM A5 < 40 mm, 72% had a platelet count less than 100. The mean and median CT were markedly different suggesting that there are outliers. Of the 151 women with data for EXTEM CT, 127 women had a CT ≤ 100, 22 women had a CT between 101 and 1000 and two women had CTs of 1814 and 3468. If the two women with CT > 1000 are excluded, the mean (SD) and median (IQR) clotting times were 93.6 (138.7) and 54 (45, 70) respectively. The median (IQR) for plasma fibrinogen levels were 6.6 (3.2–12.3) g/L.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between estimated blood loss and the coagulation parameters (maximal lysis and A5). There was no significant correlation between estimated blood loss and maximal lysis (r = 0.01, p = 0.86). There was a weak but statistically significant negative correlation between estimated blood loss and A5 (r = − 0.35, p < 0.001). After excluding women transferred from outside health facilities, the results were essentially the same (Maximal Lysis r = 0.06, p = 0.51; A5 r = − 0.46, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Although 99% deaths from PPH occur in low and middle income countries, most of the research on the haemostatic abnormalities in PPH is from high income countries [13,14,15].

Among this cohort of women who received care at a Nigerian hospital for PPH, nearly one quarter of women had findings suggestive of hyper-fibrinolysis (ML > 15%). This contrasts with studies in high-income settings where hyper-fibrinolysis is considered less common in PPH [14] de Lange et al. reported that 9% of women after normal labour had ML of > 15% within 1 h of delivery of the placenta [12] with increased D-dimer levels. Older studies looking at peri-partum changes in fibrinolysis show increases in tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) immediately after delivery, followed by increases in plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) [16, 17].

In patients with trauma, ROTEM appears to underestimate the prevalence of fibrinolytic activation compared with more sensitive measures such as plasmin-antiplasmin complexes [4]. Further studies are needed to examine which parameters are most sensitive in detecting fibrinolysis in obstetric bleeding. Although we did not find any correlation between estimated blood loss and fibrinolytic activity, inaccuracy in blood loss estimates could easily have obscured such an association. Indeed, evidence from the WOMAN trial that administration of tranexamic acid significantly reduces death due to bleeding and re-operation for bleeding, strongly suggests that fibrinolysis plays an important role in PPH. Furthermore, a randomised trial conducted in France has shown that there is an early increase in D-dimers and plasmin-antiplasmin complexes in women with active PPH and that this increase is attenuated among women who received tranexamic acid [18].

Fibrinogen levels would be expected to fall with increased fibrinolysis due to increased consumption and fibrinogenolysis. However, despite the high prevalence of hyper-fibrinolysis, the fibrinogen levels appeared to be elevated. Compared to non-pregnant women, fibrinogen levels are increased in pregnancy reaching their peak in the third trimester [19]. Nevertheless, the fibrinogen levels seen in our study are higher than in studies in high income settings. This might be related to the effects of inflammation due to acute and chronic infections including HIV and their treatments [20]. The prevalence of HIV in Nigeria is 3% and it is notable that 21% of our sample were lymphopenic. Further studies in low and middle income countries are need to confirm or refute our results.

Many women were anaemic and the degree of anaemia suggests that many were anaemic before developing PPH. Anaemia in Africa has multiple aetiologies including iron deficiency, functional iron deficiency (due infections such as malaria and HIV); genetic conditions such as sickle cell disease, thalassemia and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency; parasitic infections leading to blood loss (e.g. hookworms); and drugs such as anti-retrovirals. Furthermore, due to the expansion of the plasma volume in pregnancy, haematocrit falls. Olatunbosun et al. found that 54% of women booking into an obstetric clinic in Uyo, Nigeria were anaemic, with most having evidence of iron deficiency [21]. Women with antenatal anaemia may have an increased risk of PPH and an increased risk of severe anaemia after delivery [22, 23].

One third of women was thrombocytopenic and many were severely thrombocytopenic. This also contrasts with studies in high income countries in which thrombocytopenia is relatively uncommon [24]. The low platelet counts (in the context of the relatively well preserved coagulation factors) may explain why so many women had an EXTEM A5 < 40 mm since EXTEM A5 values are influenced by platelet and fibrinogen levels. Further studies are needed to assess the FIBTEM and EXTEM A5 levels in similar populations to differentiate the extent to which low platelet and/or fibrinogen levels impact on PPH progression. Several studies have shown that a low A5 using ROTEM FIBTEM measured during the early phase of bleeding is associated with an increased risk of severe PPH [25].

Our study has several weaknesses. Because we did not collect blood samples prior to PPH onset, we cannot determine whether the abnormal haematological values (anaemia and thrombocytopenia) observed in this study are a cause or consequence of the bleeding. Due to technical problems with either blood samples or measurement instruments, the number of patients with available data was less than the number enrolled. We did not compare our results with a control group of women who did not experience PPH. Although the women in our study were a sample (54%) of all those recruited into the WOMAN trial at University College Hospital, we do not believe they were selected based on bleeding severity. The mean blood loss among the 167 women who were included was similar to that for the 142 women enrolled in the Woman trial but not included in this ROTEM study [1530 ml (SD) 897 for the included women versus 1548 (SD) 810] in women not included in the ROTEM study]. Their systolic blood pressures at baseline were also similar [110 mmHg (27) among included women versus 103 (33) in women who were not included]. It is possible that the reason for the high prevalence of coagulopathy found in our study is that our cohort had more severe PPH than studies in high income settings.

Conclusions

Based on findings from a convenience sample of women who delivered in a teaching hospital in Nigeria, hyper-fibrinolysis occurs in nearly 25% of women with PPH. Further studies into the pathophysiological mechanisms for hyper-fibrinolysis should help us to identify better treatment strategies for women with PPH.

Abbreviations

- A5:

-

Clot amplitude (firmness) at five minutes

- aPTT:

-

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- EDTA:

-

Ethylene diamine triacetic acid

- ETAC:

-

Effect of tranexamic acid on coagulation sub-study of woman trial.

- EXTEM:

-

Extrinsic screening test on ROTEM

- g/L:

-

Grams per litre

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- INTEM:

-

Intrinsic screening test on ROTEM

- L:

-

Litre

- LSHTM:

-

London school of hygiene and tropical medicine

- MCV:

-

Mean corpuscular volume

- ML:

-

Maximum Lysis

- mL:

-

Millilitre

- mmHg:

-

Millimetre of mercury

- mol/L:

-

Moles per litre

- NAFDAC:

-

National agency for food & drug administration and control

- PAI-1:

-

Plasminogen activator inhibitors

- PPH:

-

Postpartum haemorrhage

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- QC:

-

Quality control

- ROTEM:

-

Rotational thromboelastometry

- t-PA:

-

Tissue plasminogen activator

- WOMAN Trial:

-

World maternal anti-fibrinolytic trial

References

CRASH-2 trial collaborators, Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, Caballero J, Coats T, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):23–32.

CRASH-2 collaborators, Roberts I, Shakur H, Afolabi A, Brohi K, Coats T, et al. The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9771):1096–101.

Roberts I, Prieto-Merino D, Manno D. Mechanism of action of tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of data from the CRASH-2 trial. Crit Care. 2014;18:685.

Raza I, Davenport R, Rourke C, Platton S, Manson J, Spoors C, Khan S, De'ath H, Allard S, Hart D, John Pasi K, Hunt BJ, Stanworth S, Maccallum P, Brohi K. The incidence and magnitude of fibrinolytic activation in trauma patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(2):307–14.

Chapman MP, Moore EE, Moore HB, Gonzalez E, Gamboni F, Chandler JG, Mitra S, Ghasabyan A, Chin TL, Sauaia A, Banerjee A, Silliman CC. Overwhelming tPA release, not PAI-1 degradation, is responsible for hyperfibrinolysis in severely injured trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:16–25.

Cap A, Hunt BJ. The pathogenesis of traumatic coagulopathy. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(Suppl 1):e96–101.

The WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early administration of tranexamic acid on mortality, hysterectomy, other morbidities in women with postpartum haemorrhage (the WOMAN trial): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10084):2105–16.

Wikkelsø AJ, Edwards HM, Afshari A, Stensballe J, Langhoff-Roos J, Albrechtsen C, Ekelund K, Hanke G, Secher EL, Sharif HF, Pedersen LM, Troelstrup A, Lauenborg J, Mitchell AU, Fuhrmann L, Svare J, Madsen MG, Bødker B, Møller AM, FIB-PPH trial group. Pre-emptive treatment with fibrinogen concentrate for postpartum haemorrhage: randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114:623–33.

World Health Organization (WHO). The prevalence of Anaemia in women: a tabulation of available information. Geneva: WHO; 1992. WHO/MCH/MSM/92.2

Brohi K, Singh J, Heron M, Coats T. Acute traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma. 2003;54:1127–30.

Hagemo JS, Christiaans SC, Stanworth SJ, et al. Detection of acute traumatic coagulopathy and massive transfusion requirements by means of rotational thromboelastometry: an international prospective validation study. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):97.

de Lange NM, van Rheeneen-Flach LE, Lance MD, Mooyman L, et al. Peri-partum reference ranges for ROTEM®thromboelastometry. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112(5):852–9.

Ronsmans C, Graham WJ. Lancet maternal survival series steering group: maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1189–200.

Solomon C, Collis R, Collins P. Haemostatic monitoring during postpartum haemorrhage and implications for management. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(6):851–63.

Erhabor O, Isaac I, Muhammad A, Abdulrahman Y, Ezimah A, Adias T. Some hemostatis parameters in women with obstetric haemorrhage in Sokoto, Nigeria. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:285–91.

Mackinnon S, Walker ID, Davidson JF, Walker JJ. Plasma fibrinolysis during and after normal childbirth. Br J Haematol. 1987;65:339–42.

Bremer HA, Brommer EJP, Wallenburg HCS. Effects of labour and delivery on fibrinolysis. Eur J Ob Gynaecol Repro Biol. 1994;55:163–8.

Ducloy-Bouthors AS, Duhamel A, Kipnis E, Tournoys A, Prado-Dupont A, Elkalioubie A, Jeanpierre E, Debize G, Peynaud-Debayle E, DeProst D, Huissoud C, Rauch A, Susen S. Postpartum haemorrhage related early increase in D-dimers is inhibited by tranexamic acid: haemostasis parameters of a randomized controlled open labelled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116:641–8.

Okwesili A, Ibrahim K, Nnadi D, Barnabas B, Abdulrahaman Y, Buhari H, Udomah F, Imoru M, Egenti B, Erhabor O. Fibrinogen levels among pregnant women of African descent in Sokoto north western Nigeria. Front Biomed Sci. 2016;1(2):7–11.

Madden E, Lee G, Kotler DP, et al. Association of Antiretroviral Therapy with fibrinogen levels in HIV infection. AIDS. 2008;22(6):707–15.

Olatunbosun O, Abasiattai A, Bassey E, James R, Ibanga G, Morgan A. Prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women at booking in the University of Uyo Teaching Hospital. Uyo: Biomed Research International; 2014. Article ID: 849080

Nair M, Choudhry MK, Choudhry SS, Kakoty SD, Sarma UC, Webster P, et al. Association between maternal anaemia and pregnancy outcome: a cohort study in Assam, India. BMJ Global Health. 2016;1:e000026.

Butwick A, Walsh E, Kuzniewicz M, Li S, Escobar G. Patterns and predictors of severe postpartum anemia after cesarean section. Transfusion. 2017;57:36–44.

Jones RM, de Lloyd L, Kealaher EJ, Lilley GJ, Precious E, Burckett st Laurent D, Hamlyn V, Collis RE, Collins PW, collaborators. Platelet count and transfusion requirements during moderate or severe postpartum haemorrhage. Anaesthesia. 2016;71:648–56.

Collins PW, Lilley G, Bruynseels D, et al. Fibrin-based clot formation as an early and rapid biomarker for progression of postpartum hemorrhage: a prospective study. Blood. 2014;124:1727–36.

Funding

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK Department of Health, Wellcome Trust, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded the WOMAN trial. An educational grant, equipment and consumables for ROTEM analysis was provided by tem innovations GmbH, M.-Kollar-Str. 13–15, 81829 Munich, Germany to LSHTM and utilised fully at the university college hospital, Ibadan. The funders had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available from HS and IR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IR and HS conceived the study, contributed data cleaning, statistical analysis and writing of the manuscript. BK contributed to protocol development and had overall responsibility for the study at the trial site and review of the manuscript. OO contributed to protocol development and is the site principal investigator for WOMAN trial and review of the manuscript. MK contributed to the protocol development and was responsible for overseeing laboratory tests, laboratory standard operating procedures and staff training and review of the manuscript. AB contributed to protocol development and was responsible for data transfer and review of the manuscript. OO contributed to the protocol development, development of the standard operating procedures and was responsible for participant recruitment and review of the manuscript. CA contributed to the protocol development and was responsible for participant recruitment and review of the manuscript. TK contributed to the protocol development and was responsible for routine laboratory tests and review of the manuscript. BH contributed to data cleaning and writing of the manuscript. SH conducted the statistical analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. TO was responsible for overseeing laboratory tests, laboratory standard operating procedures and staff training and review of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approvals to conduct this study were obtained from the Ethics Committees of London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the University of Ibadan & University College Hospital Ethics Committee. Regulatory approval was obtained from the Nigerian National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC). The study was undertaken according to ICH-GCP guidelines. The consent procedures is detailed in the WOMAN Trial protocol [22]. Briefly, we obtained written consent from a patient if their physical and mental capacity allowed. If a patient could not give written consent, we obtained proxy consent from a relative or representative. If a proxy was unavailable, then if local regulation allows, we deferred or waived consent. In this situation, we informed the patient about the trial as soon as possible, and obtained written consent to use the data. The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine is the sponsor.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Roberts, I., Shakur, H., Fawole, B. et al. Haematological and fibrinolytic status of Nigerian women with post-partum haemorrhage. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1794-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1794-1